Dominion Geometries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Central Vista.Pdf

RASHTRAPATI BHAVAN and the Central Vista © Sondeep Shankar Delhi is not one city, but many. In the 3,000 years of its existence, the many deliberations, decided on two architects to design name ‘Delhi’ (or Dhillika, Dilli, Dehli,) has been applied to these many New Delhi. Edwin Landseer Lutyens, till then known mainly as an cities, all more or less adjoining each other in their physical boundary, architect of English country homes, was one. The other was Herbert some overlapping others. Invaders and newcomers to the throne, anxious Baker, the architect of the Union buildings at Pretoria. to leave imprints of their sovereign status, built citadels and settlements Lutyens’ vision was to plan a city on lines similar to other great here like Jahanpanah, Siri, Firozabad, Shahjahanabad … and, capitals of the world: Paris, Rome, and Washington DC. Broad, long eventually, New Delhi. In December 1911, the city hosted the Delhi avenues flanked by sprawling lawns, with impressive monuments Durbar (a grand assembly), to mark the coronation of King George V. punctuating the avenue, and the symbolic seat of power at the end— At the end of the Durbar on 12 December, 1911, King George made an this was what Lutyens aimed for, and he found the perfect geographical announcement that the capital of India was to be shifted from Calcutta location in the low Raisina Hill, west of Dinpanah (Purana Qila). to Delhi. There were many reasons behind this decision. Calcutta had Lutyens noticed that a straight line could connect Raisina Hill to become difficult to rule from, with the partition of Bengal and the Purana Qila (thus, symbolically, connecting the old with the new). -

1 the Prime Minister, Prime Minister's Office South Block, Raisina Hill

1 The Prime Minister, Prime Minister's Office South Block, Raisina Hill New Delhi-110011, INDIA Subject : www.isdbweb.org Oxytocin and related scientific information. The Committee Utrecht 27 November 2019 Dear Prime Minister, Chairman Dick Bijl The International Society of Drug Bulletins (https://www.isdbweb.org/) Folia Pharmacotherapeutica Vredenburgplein 40, 3511 WH Utrecht is a worldwide network of bulletins and journals on drugs and The Netherlands therapeutics that are financially and intellectually independent of the E-mail: [email protected] pharmaceutical industry. It was founded in 1986, with the support of the General Secretary World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. The aim of the Nuria Homedes Boletin Farmacos Society is to support the analyses and dissemination of scientific drug USA information to promote access and the appropriate use of E-mail: [email protected] pharmaceuticals. Treasurer ISDB learned that Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of India in its Luis Carlos Saiz BIT Navarra / DTB Navarre circular dated 1st August 2018, “has restricted the manufacture of Spain oxytocin formulations for domestic use to public sector only from 1st E-mail: [email protected] 1 September, 2018, due to complaints of misuse.” Rita Kessler As per a media report, this particular restriction is based on a complaint La revue Prescrire France of “misuse” of oxytocin and is as quoted below: E-mail: [email protected] “Reacting to Maneka’s concerns, the Health Ministry, through the Maria Font director general (health -

OLD Brochure Open Source File

BP A Home For Everyone Housing x City Mart, Sohna Road, G Floor, Nine urgaon, H 14, 2nd aryana e : +91 0124-4000791, 84689 Phon 98877 .com | info@abpde aniaresidency velopers.c info@rom om aresidency.com | www.abpd .romani evelope www rs.com A Home For Everyone At The Gateway Of Delhi DISCLAIMER This booklet design is purely conceptual and not a legal offering. The information, dimensions and specifications mentioned BP herein are subject to change and may vary from the actual development. This publication should not be construed in any way Housing as a legal offer or invitation to offer. All images are artistic conceptualization and do not purport to replicate the exact product. www.romaniaresidency.com | www.abpdevelopers.com A Home For Everyone A Good Home is Heaven On Earth With a desire to provide a home for everyone with aordable pricing, ABP Housing Projects Pvt. Ltd. brings to you an opportunity of lifetime in form of its dream integrated project Romania Residency- an exclusive gated, secured, well planned development in Delhi. With an option of 2 & 3 BHK apartments with ultra modern facilities & an aesthetic landscaping surrounded by beautiful ample of green belt, Romania Residency gives you a life set in luxury and a quality of living that equals the very best. Lavish outdoor and indoor spaces, state-of-the-art club house and shopping centre, all just a walk away complete the living experience at the Romania Residency. Its premium location on L-Zone adjacent to the Airport, Upcoming Diplomatic Enclave & Dwarka-Gurgaon Expressway and being in close vicnity of multiple mega industrial and commercial developments, world famous educational institute and with its great heritage of history make Romania Residency a unique investment option. -

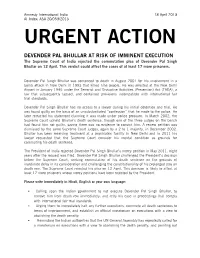

DEVENDER PAL BHULLAR at RISK of IMMINENT EXECUTION the Supreme Court of India Rejected the Commutation Plea of Devender Pal Singh Bhullar on 12 April

Amnesty International India 18 April 2013 AI Index: ASA 20/059/2013 URGENT ACTION DEVENDER PAL BHULLAR AT RISK OF IMMINENT EXECUTION The Supreme Court of India rejected the commutation plea of Devender Pal Singh Bhullar on 12 April. This verdict could affect the cases of at least 17 more prisoners. Devender Pal Singh Bhullar was sentenced to death in August 2001 for his involvement in a bomb attack in New Delhi in 1993 that killed nine people. He was arrested at the New Delhi Airport in January 1995 under the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA), a law that subsequently lapsed, and contained provisions incompatible with international fair trial standards. Devender Pal Singh Bhullar had no access to a lawyer during his initial detention and trial. He was found guilty on the basis of an unsubstantiated “confession” that he made to the police. He later retracted his statement claiming it was made under police pressure. In March 2002, the Supreme Court upheld Bhullar’s death sentence, though one of the three judges on the bench had found him not guilty, saying there was no evidence to convict him. A review petition was dismissed by the same Supreme Court judges, again by a 2 to 1 majority, in December 2002. Bhullar has been receiving treatment at a psychiatric facility in New Delhi and in 2011 his lawyer requested that the Supreme Court consider his mental condition as grounds for commuting his death sentence. The President of India rejected Devender Pal Singh Bhullar’s mercy petition in May 2011, eight years after the request was filed. -

Narayani.Pdf

OUR CITY, DELHI Narayani Gupta Illustrated by Mira Deshprabhu Introduction This book is intended to do two things. It seeks to make the child living in Delhi aware of the pleasures of living in a modern city, while at the same time understanding that it is a historic one. It also hopes to make him realize that a citizen has many responsibilities in helping to keep a city beautiful, and these are particularly important in a large crowded city. Most of the chapters include suggestions for activities and it is important that the child should do these as well as read the text. The book is divided into sixteen chapters, so that two chapters can be covered each month, and the course finished easily in a year. It is essential that the whole book should be read, because the chapters are interconnected. They aim to make the child familiar with map-reading, to learn some history without making it mechanical, make him aware of the need to keep the environment clean, and help him to know and love birds, flowers and trees. Our City, Delhi Narayani Gupta Contents Introduction Where Do You Live? The Ten Cities of Delhi All Roads Lead to Delhi Delhi’s River—the Yamuna The Oldest Hills—the Ridge Delhi’s Green Spaces We Also Live in Delhi Our Houses Our Shops Who Governs Delhi? Festivals A Holiday Excursion Delhi in 1385 Delhi in 1835 Delhi in 1955 Before We Say Goodbye 1. Where Do You Live? This is a book about eight children and the town they live in. -

317 the Street Names of New Delhi

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.academicsjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 3; May 2017; Page No. 317-322 The street names of New Delhi Nidhi M.A (F), Delhi School of Economics, Delhi, India Introduction the years in terms of linguistic changes. Language in turn is Unravelling Street Names related to the race or communities inhabiting that place. The study of street names highlights some important points. Therefore, distribution of communities also helps in First, street names indicate about the geographic understanding the value of street names. characteristics or geological past of the local area. The Sixth, study of street names of recent origin help to unravel geographical location of a place influences street the present factors which cause regulation of street names. The nomenclature. For example- if a street is located on higher principles of street naming are affected by the pattern of urban ground, then it is named as High street. growth and economic activities which are found in the nearby Second, historic stories may be derived from street names. areas like commercial, residential or recreational places. Some of them are named after the monuments located near to them or some memorable event. Religious sites also play an Objective of the Study important role, for example- Mandir Marg. Third, street names The main objective of the study is as follows:- are given to honour dignitaries for their service to nation. To study the meanings of Street names of New Delhi. Fourth, as a place is discovered by kings, queens or colonial rulers, the streets are named by them. -

Saksham Sak S

SAKSHAM Measures for Ensuring the Safety of Women SAK and Programmes for Gender Sensitization on S Campuses HAM University Grants Commission Bahadurshah Zafar Marg New Delhi SAKSHAM Measures for Ensuring the Safety of Women and Programmes for Gender Sensitization on Campuses SAKSHAM Measures for Ensuring the Safety of Women and Programmes for Gender Sensitization on Campuses University Grants Commission Bahadurshah Zafar Marg New Delhi © University Grants Commission December 2013 All Rights Reserved Published by Secretary University Grants Commission, Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, New Delhi-110002 Designed and Printed by : Deeya Media Art, D-41/A, Laxmi Nagar, Delhi-110092 Ph. : 9312550335, 9211656230 iv Table of Contents Preface ...................................................................................................................................vii Letter of Submission ..............................................................................................................ix Acknowledgements ...............................................................................................................xi List of Members of the Task Force ....................................................................................xiii Executive Summary .............................................................................................................01 I. INTRODUCTION 09 1.1 Higher Education and Gender in Contemporary India ............................................09 1.2 Sexual Violence and Harassment in the Contemporary -

LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version)

Tt'nth Series, Vol. XLIV, No. 11 Monday, August 21, 1995 Sravana 30,1917 (Saka) LOK SABHA DEBATES (English Version) Fourteenth Session (Tenth Lok Sabha) . (Vol. XLIV Contains Nos. 11 to 16) LOi( SARHA SECRETARIAT NEW DElHI Price: Rs. 50.00 Q)RRIGE~TO llK,§~~Hf;Lg~~r~ (English Venion) Monday, August 21, 1995JSravana 30, 1917 (Saka) •• 53/9(from below) Shri Praja Kishore Shri 8raja Kishore Tripathy Tripathy 54/13 {from below} Or. K.o .JESWANT Dr.K.D. Jeswani 62/7 I Dr.Anlrit Lal Kalial Dr. Arnrit Lal Kalitias 89/4 Patel Patel 90/3 72/16(from below) M)U with 11alayscia W,)IJ with Malaysia 83/22. The Minister of The Minister of State 169/16(from below) State in the Ministry 1n the Ministry,of of Power (Shrimati Power (Shrimati UrmUaben Patel): urmilaben Olimanbhai Patel): 115/2 Shri Uddhor Barman 3hri Udl.lhab Sarman 128/23 Shri Jeewn Sharma 5hri Jeewan Sharma 2'25/21 Shri Inderjit Gupta Shri Indrajit Gupta I~ ENGusH ~ .•1Ncwoeo 1N.·fHGusH VeAsot.AND ORIGINAi. ·HINDt I'ROCE£DINGS fNcwoeo IN HIta· VEASnl . WIlL IE TREAtED 118 AI.ITHORITATNE· AND HOt· TIE iRANst.ATlON THEREOF1 CONTENTS Tenth Series Vol. XLIV, Fourtennth Session, 1995/1917 (Saka) No. 11, Monday,. August 21,1995/ Sravana 30,1917 (Saka) Column WRITTEN ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS: 'Starred Questions Nos. 241 - 260 1-17 Unstarred Questions Nos. 2398 - 2481 and 2483 - 2627 18-192 STATEMENT BY PRIME MINISTER 192 TRAIN ACCIDENT INVOLVING PURUSHOTTAM Express and Kalindi Express Near Firozabad Shri P.V. Narasimha Rao 192-193 PAPERS LAID ON THE TABLE 209-210 STANDING COMITTEE ON COMMERCE 211 Fifteenth Report - Laid CRIMINAL LAW (Second Amendment) BILL -Indroduced 211 DISCUSSION UNDER RULE 193 215-299 TRAIN ACCIDENT INVOLVING PURUSHOTTAM EXPRESS AND KALINDI EXPRESS NEAR FIROZABAD Shri Alai Bihari Vajpayee 215-219 Shri Somnath Chatterjee 219-228 Shri Ram Vilas Paswan 228-231 Shri Prabhu Dayal Katheria 231-232 Shri Arjun Singh 232-234 Dr. -

While a Dwindling Community Struggles to Survive, Filmmaker

Article on Parsis of Delhi While a dwindling community struggles to survive, filmmaker Shernaz Italia documents the little-known lives of the Delhi Parsis who moved to the capital at the turn of the 19th century “Aavoji, aavo, aavo! Welcome to Delhi! Let me show you my beautiful city.” The booming voice of Nowrosji Kapadia could be heard across the length and breadth of the platform. It was Nowrosji’s favourite pastime: a walk to the Old Delhi railway station to greet the Frontier Mail as it chugged into Delhi from Mumbai to Peshawar. With this refrain, an eager Nowrosji would cajole Parsi visitors off the train and take them home for a meal and often persuade some to stay overnight or for a few days. He would use this opportunity to tell them about the advantages of shifting to Delhi. Though his wife Jer Bai would occasionally object to unknown visitors, she was always overruled. This was the beginning of the community of Parsis in Delhi. Nowrosji Kapadia was one of the oldest Parsi residents of Delhi. He was born in Bharuch, a small town in Gujarat. He opted out of his family’s failing cloth business and got a job as an agent with the European firm Ralli Brothers. They sent him to Delhi in 1880. Why did he not want to return to Bharuch, or Bombay, where our community still resides in large numbers? Was it business sense, apt foresight of Delhi’s growing importance, or was he just different? A few other Parsi families moved northwards to Delhi and beyond in the 1870s–80s. -

IPG Delhi Conference

Full Day City Heritage Tour Timings: 0930 hours – 1700 hours You will set out from your hotel in an air-conditioned car/coach for a sightseeing tour in New Delhi, the capital of India. A local English-speaking guide will accompany you on this excursion. You will visit the following famous landmarks of the city: Qutub Minar: The tallest hand carved brick minaret in the world at 72.5 meters, it is one of the finest examples of Indo- Islamic architecture. Construction began in the 12th century by the slave king Qutubuddin Aibak, from whose name the minaret gets its name. In the same complex is a mosque and iron pillar, which has not rusted even after 1,500 years. Humayun's Tomb: The mausoleum of the Mughal Emperor Humayun. It was built in 1570 by the emperor's widow, Haji Begum. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, it was the first garden tomb of India and a forerunner of the Mughal style of architecture, with high arches and formal gardens (charbagh). Red Fort: One of the most spectacular pieces of Mughal Architecture is the Lal Quila or the Red Fort. Built by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan between 1638 and 1648, the Red Fort has walls extending up to 2 km in length with the height varying from 18 m on the riverside to 33 m on the city side. India Gate: A 40 meter high war memorial arch dedicated to Indian soldiers who died in World War I. Rashtrapati Bhawan: The President's residence and formerly the Viceroy's Palace, this building is constructed on top of Raisina Hill. -

Achievement of New Delhi Municipal Council in Last 7 Months

NDMC : THE FACE OF A SMART CITY NEW DELHI MUNICIPAL COUNCIL( NDMC) • NDMC SPREAD OVER 43 SQ.KM AREA, RESIDENT POPULATION ABOUT 3 LAKHS • FLOATING POPULATION DURING DAY ABOUT 16 LAKHS • DENSITY POPULATION OF 7000 PERSONS PER SQ. KM BRIEF HISTORY OF NDMC • In 1911, SHIFT of Capital from Calcutta to Delhi. • Site of New Capital- RAISINA HILL. • The IMPERIAL DELHI COMMITTEE: Constituted on 25th March, 1913. • RAISINA MUNICIPAL COMMITTEE formed in 1916. • 1932: NEW DELHI MUNICIPAL COMMITTEE WAS FORMED AS A 1ST CLASS MUNICIPALITY. ENTRUSTED WITH SUPERVISORY POWERS TO LOOK AFTER ALL THE SERVICES AND ACTIVITIES . • IN MAY 1994, THE NDMC ACT 1994, THE COMMITTEE WAS RENAMED AS THE NEW DELHI MUNICIPAL COUNCIL. CONSTITUTION OF THE COUNCIL • 13 MEMBER COUNCIL HEADED BY A CHAIRPERSON GOVERNS THE NDMC. • COMPOSITION: – MP LOKSABHA (NEW DELHI PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCY) – 2 MLAs (NEW DELHI AND DELHI CANTT ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES) – 5 OFFICIAL MEMBERS NOMINATED BY THE CENTRAL GOVERNMENT (3 FROM GOI and 2 FROM GNCTD) – 4 NON OFFICIAL MEMBERS INCLUDING A VICE CHAIR PERSON, NOMINATED BY THE CENTRAL GOVERNMENTIN CONSULTATION WITH THE CHIEF MINSTER OF DELHI TO REPRESENT EMINENT PEOPLE FROM DIFFERENT FIELDS * 3 MEMBERS TO BE WOMEN * 2 MEMBERS FROM SCHEDULED CASTE( ONE NON-OFFICIAL NOMINATION) . BRIEF PROFILE OF NDMC • REPRESENTS THE HEART OF THE NATIONAL CAPITAL • SEAT OF THE HEAD OF THE LEGISLATURE ,EXECUTIVE AND THE JUDICIARY • CLEANEST AND GREENEST PART OF THE CAPITAL-1450 ACRES GREEN AREA • 43 SQ.KM AREA, RESIDENT POPULATION - 3 LAKHS (floating population during day about 16 lakhs), DENSITY - 7000 PERSONS PER SQ. KM • REPLETE WITH HERITAGE MONUMENTS, COMMERCIAL CENTERS, ART AND CULTURE HUB • 167 KMS MAIN ROADS, 394 COLONY ROADS - 170 KM • 450 KM WATER LINE , 300 KMS MAIN SEWER LINES, 16 SUBWAYS , 197 BUS-Q-SHELTERS • TOTAL 70 SCHOOLS FROM NURSERY TO SENIOR SECONDARY. -

A Century of New Delhi: Political Reform, Questions of Finance, and the Creation of a New Capital for India / Xix

National Archives of India 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in India by Oxford University Press YMCA Library Building, 1 Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 110 001, India © National Archives of India 2014 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer ISBN-13: 978-0-19-808499-0 ISBN-10: 0-19-808499-4 Typeset in Bembo Std 11.5/14 by Le Studio Graphique, Gurgaon 122 001 Printed in India by G.H. Prints Pvt Ltd, New Delhi 110 020 The text of all documents has been retained as in the original, except in the case of obvious typographical errors. In some cases, errors noted by the editors have been pointed out by using sic. Contents List of Documents / vii A Century of