JETIR Research Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princely Palaces in New Delhi Datasheet

TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +1 212 645 1111 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/us Princely Palaces In New Delhi Sumanta K Bhowmick ISBN 9789383098910 Publisher Niyogi Books Binding Hardback Territory USA & Canada Size 9.18 in x 10.39 in Pages 264 Pages Price $75.00 The first-ever comprehensive book on the princely palaces in New Delhi Documentation based on extensive archival research and interviews with royal families Text supported by priceless photographs obtained from the private collections of the princely states, National Archives of India, state archives and various other government and private bodies Rajas and maharajas from all over the British Indian Empire congregated in Delhi to attend the great Delhi Durbar of 1911. A new capital city was born New Delhi. Soon after, the princely states came up with elaborate palaces in the new Imperial capital Hyderabad House, Baroda House, Jaipur House, Bikaner House, Patiala House, to name a few. Why did the British government allot prime land to the princely states and how? How did the construction come up and under whose architectural design? Who occupied these palaces and what were the events held? What happened to these palatial buildings after the integration of the states with the Indian Republic? This book delineates the story behind the story, documenting history through archival research, interviews with royalty and unpublished photographs from royal private collections. Contents: Foreword; The Journey; Living with History; Hyderabad House- Guests of Honour; Baroda House - Butterfly on the Track; Bikaner House -Rajasthan Royals; Jaipur House -An Acre of Art; Patiala House -Chambers of Justice; Travancore House -Hathiwali Kothi; Darbhanga House - The 'Twain Shall Meet; The Other Palaces - Scattered Petals; Planning the Palaces -Thy Will be Done; List of Princely Palaces. -

Rashtrapati Bhavan and the Central Vista.Pdf

RASHTRAPATI BHAVAN and the Central Vista © Sondeep Shankar Delhi is not one city, but many. In the 3,000 years of its existence, the many deliberations, decided on two architects to design name ‘Delhi’ (or Dhillika, Dilli, Dehli,) has been applied to these many New Delhi. Edwin Landseer Lutyens, till then known mainly as an cities, all more or less adjoining each other in their physical boundary, architect of English country homes, was one. The other was Herbert some overlapping others. Invaders and newcomers to the throne, anxious Baker, the architect of the Union buildings at Pretoria. to leave imprints of their sovereign status, built citadels and settlements Lutyens’ vision was to plan a city on lines similar to other great here like Jahanpanah, Siri, Firozabad, Shahjahanabad … and, capitals of the world: Paris, Rome, and Washington DC. Broad, long eventually, New Delhi. In December 1911, the city hosted the Delhi avenues flanked by sprawling lawns, with impressive monuments Durbar (a grand assembly), to mark the coronation of King George V. punctuating the avenue, and the symbolic seat of power at the end— At the end of the Durbar on 12 December, 1911, King George made an this was what Lutyens aimed for, and he found the perfect geographical announcement that the capital of India was to be shifted from Calcutta location in the low Raisina Hill, west of Dinpanah (Purana Qila). to Delhi. There were many reasons behind this decision. Calcutta had Lutyens noticed that a straight line could connect Raisina Hill to become difficult to rule from, with the partition of Bengal and the Purana Qila (thus, symbolically, connecting the old with the new). -

Centrespread Centrespread 15 JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017 All the JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017

14 centrespread centrespread 15 JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017 All The JULY 30-AUGUST 05, 2017 takes you through ET Magazine Presidents’On Tuesday, Ram Nath Kovind moved in as the 14th President Houses to occupy Rashtrapati Bhawan, the official residence of the Indian President. the history and the peoplepresidential behind palacesthe palatial around residence, the world: and a glimpse into other :: Indulekha Aravind Presidential Residences Around The World ELYSEE PALACE, PARIS The official residence of the President of Rashtrapati Bhawan: A Brief History France since 1848, Elysee Palace was opened Cast Of Characters the building to move construction materials and subsoil water in 1722. An example of the French Classical pumped to the surface for all water requirements. style, it has 356 rooms spread over Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker 11,179 sq m n 1911, during the Delhi Durbar, it was decided that British The bulk of the land belonged to the then-maharaja of Jaipur, were the architects of the Viceroy’s India’s capital would be shifted from Calcutta to Delhi. With Sawai Madho Singh II, who gifted the 145-ft Jaipur Column to House and it was Lutyens who conceived THE WHITE HOUSE, the new capital, a new imperial residence also had to be the British to commemorate the creation of Delhi as the new the H-shaped building I WASHINGTON DC found. The original choice was Kingsway Camp in the north but capital. Though the initial idea was to finish the construction The home of the US President is spread it was rejected after experts said the region was at the risk of in four years, it finally took more than 17 years to complete, across six levels, with 132 rooms The main building was constructed under the supervision of flooding. -

India Architecture Guide 2017

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Zone 1: Zanskar Geologically, the Zanskar Range is part of the Tethys Himalaya, an approximately 100-km-wide synclinorium. Buddhism regained its influence Lungnak Valley over Zanskar in the 8th century when Tibet was also converted to this ***** Zanskar Desert ཟངས་དཀར་ religion. Between the 10th and 11th centuries, two Royal Houses were founded in Zanskar, and the monasteries of Karsha and Phugtal were built. Don't miss the Phugtal Monastery in south-east Zanskar. Zone 2: Punjab Built in 1577 as the holiest Gurdwara of Sikhism. The fifth Sikh Guru, Golden Temple Rd, Guru Arjan, designed the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) to be built in Atta Mandi, Katra the centre of this holy tank. The construction of Harmandir Sahib was intended to build a place of worship for men and women from all walks *** Golden Temple Guru Ram Das Ahluwalia, Amritsar, Punjab 143006, India of life and all religions to come and worship God equally. The four entrances (representing the four directions) to get into the Harmandir ਹਰਿਮੰਦਿ ਸਾਰਹਬ Sahib also symbolise the openness of the Sikhs towards all people and religions. Mon-Sun (3-22) Near Qila Built in 2011 as a museum of Sikhism, a monotheistic religion originated Anandgarh Sahib, in the Punjab region. Sikhism emphasizes simran (meditation on the Sri Dasmesh words of the Guru Granth Sahib), that can be expressed musically *** Virasat-e-Khalsa Moshe Safdie Academy Road through kirtan or internally through Nam Japo (repeat God's name) as ਰਿਿਾਸਤ-ਏ-ਖਾਲਸਾ a means to feel God's presence. -

1 the Prime Minister, Prime Minister's Office South Block, Raisina Hill

1 The Prime Minister, Prime Minister's Office South Block, Raisina Hill New Delhi-110011, INDIA Subject : www.isdbweb.org Oxytocin and related scientific information. The Committee Utrecht 27 November 2019 Dear Prime Minister, Chairman Dick Bijl The International Society of Drug Bulletins (https://www.isdbweb.org/) Folia Pharmacotherapeutica Vredenburgplein 40, 3511 WH Utrecht is a worldwide network of bulletins and journals on drugs and The Netherlands therapeutics that are financially and intellectually independent of the E-mail: [email protected] pharmaceutical industry. It was founded in 1986, with the support of the General Secretary World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. The aim of the Nuria Homedes Boletin Farmacos Society is to support the analyses and dissemination of scientific drug USA information to promote access and the appropriate use of E-mail: [email protected] pharmaceuticals. Treasurer ISDB learned that Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of India in its Luis Carlos Saiz BIT Navarra / DTB Navarre circular dated 1st August 2018, “has restricted the manufacture of Spain oxytocin formulations for domestic use to public sector only from 1st E-mail: [email protected] 1 September, 2018, due to complaints of misuse.” Rita Kessler As per a media report, this particular restriction is based on a complaint La revue Prescrire France of “misuse” of oxytocin and is as quoted below: E-mail: [email protected] “Reacting to Maneka’s concerns, the Health Ministry, through the Maria Font director general (health -

Cpwd Contact Us

CPWD CONTACT US Sl. Issues Designation Tele. No. Fax No. E-mail Address No. 1 As Under Addl. DG (S&P) 23061772 23062097 [email protected] (1) Chief Engineer, 23062284 23061355 [email protected] NDZ-I (i) Superintending 23378938 23378938 [email protected] Engineer Delhi 23370942 Central Circle -II Maintenance related with matters Executive Engineer 23378102/ 23378938 [email protected] related to maintenance of LBZ B-Division 23379307 bungalows occupied by Cabinet/State Ministers, Secretary(UD), Cabinet Secretary, Furniture for Members of Planning Commission etc. Matters related to maintenance of Executive Engineer 23370069 23378938 [email protected] LBZ bungalows occupied by I – Division Supreme Court/High Court Judges, Bungalows of Director, CBI, Secy/Raw, Chairman of various commissions, SC/T commission, CVC, NSA, Principal Secy.to PM, Defence Officers etc. & Secretary, Gandhi Smiriti, Lal Bahadur Shastri Memorial & SSB office. Matters related to maintenance of Executive Engineer 23019299 23013852 EE_EDIVISION@hotm LBZ bungalows occupied by Prime E-Division ail.com Minister, Vice President, ex-PMs, 10,Janpath, 5, Telegraph Lane, 35, Lodhi Estate, 12, Tughlak Lane, PM Office, Hyderabad House, Teen Murti House Indira Gandhi Memorial Trust etc. Matters related to maintenance of Executive Engineer 23015801 23015600 [email protected] North Block, South Block, Vijay Central Secretariat Chowk, L & M Block, INS, Vayu Division Bhavan (ii) Superintending 23378168 23378462 [email protected] Engineer Delhi Central Circle -IV Maintenance -

OLD Brochure Open Source File

BP A Home For Everyone Housing x City Mart, Sohna Road, G Floor, Nine urgaon, H 14, 2nd aryana e : +91 0124-4000791, 84689 Phon 98877 .com | info@abpde aniaresidency velopers.c info@rom om aresidency.com | www.abpd .romani evelope www rs.com A Home For Everyone At The Gateway Of Delhi DISCLAIMER This booklet design is purely conceptual and not a legal offering. The information, dimensions and specifications mentioned BP herein are subject to change and may vary from the actual development. This publication should not be construed in any way Housing as a legal offer or invitation to offer. All images are artistic conceptualization and do not purport to replicate the exact product. www.romaniaresidency.com | www.abpdevelopers.com A Home For Everyone A Good Home is Heaven On Earth With a desire to provide a home for everyone with aordable pricing, ABP Housing Projects Pvt. Ltd. brings to you an opportunity of lifetime in form of its dream integrated project Romania Residency- an exclusive gated, secured, well planned development in Delhi. With an option of 2 & 3 BHK apartments with ultra modern facilities & an aesthetic landscaping surrounded by beautiful ample of green belt, Romania Residency gives you a life set in luxury and a quality of living that equals the very best. Lavish outdoor and indoor spaces, state-of-the-art club house and shopping centre, all just a walk away complete the living experience at the Romania Residency. Its premium location on L-Zone adjacent to the Airport, Upcoming Diplomatic Enclave & Dwarka-Gurgaon Expressway and being in close vicnity of multiple mega industrial and commercial developments, world famous educational institute and with its great heritage of history make Romania Residency a unique investment option. -

Town Planning & Human Settlements

AR 0416, Town Planning & Human Settlements, UNIT I INTRODUCTION TO TOWN PLANNING AND PLANNING CONCEPTS CT.Lakshmanan B.Arch., M.C.P. AP(SG)/Architecture PRESENTATION STRUCTURE INTRODUCTION PLANNING CONCEPTS • DEFINITION • GARDEN CITY – Sir Ebenezer • PLANNER’S ROLE Howard • AIMS & OBJECTIVES OF TOWN • GEDDISIAN TRIAD – Patrick Geddes PLANNING • NEIGHBOURHOOD PLANNING – • PLANNING PROCESS C.A.Perry • URBAN & RURAL IN INDIA • RADBURN LAYOUT • TYPES OF SURVEYS • EKISTICS • SURVEYING TECHNIQUES • SATELLITE TOWNS • DIFFERENT TYPE OF PLANS • RIBBON DEVELOPMENT TOWN PLANNING “A city should be built to give its inhbhabitants security and h”happiness” – “A place where men had a Aristotle common life for a noble end” –Plato people have the right to the city Town planning a mediation of space; making of a place WHAT IS TOWN PLANNING ? The art and science of ordering the use of land and siting of buildings and communication routes so as to secure the maximum practicable degree of economy, convenience, and beauty. An attempt to formulate the principles that should guide us in creating a civilized physical background for human life whose main impetus is thus … foreseeing and guiding change. WHAT IS TOWN PLANNING ? An art of shaping and guiding the physical growth of the town creating buildings and environments to meet the various needs such as social, cultural, economic and recreational etc. and to provide healthy conditions for both rich and poor to live, to work, and to play or relax, thus bringing about the social and economic well-being for the majority of mankind. WHAT IS TOWN PLANNING ? • physical, social and economic planning of an urban environment • It encompasses many different disciplines and brings them all under a single umbrella. -

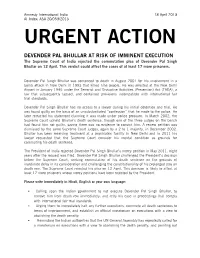

DEVENDER PAL BHULLAR at RISK of IMMINENT EXECUTION the Supreme Court of India Rejected the Commutation Plea of Devender Pal Singh Bhullar on 12 April

Amnesty International India 18 April 2013 AI Index: ASA 20/059/2013 URGENT ACTION DEVENDER PAL BHULLAR AT RISK OF IMMINENT EXECUTION The Supreme Court of India rejected the commutation plea of Devender Pal Singh Bhullar on 12 April. This verdict could affect the cases of at least 17 more prisoners. Devender Pal Singh Bhullar was sentenced to death in August 2001 for his involvement in a bomb attack in New Delhi in 1993 that killed nine people. He was arrested at the New Delhi Airport in January 1995 under the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA), a law that subsequently lapsed, and contained provisions incompatible with international fair trial standards. Devender Pal Singh Bhullar had no access to a lawyer during his initial detention and trial. He was found guilty on the basis of an unsubstantiated “confession” that he made to the police. He later retracted his statement claiming it was made under police pressure. In March 2002, the Supreme Court upheld Bhullar’s death sentence, though one of the three judges on the bench had found him not guilty, saying there was no evidence to convict him. A review petition was dismissed by the same Supreme Court judges, again by a 2 to 1 majority, in December 2002. Bhullar has been receiving treatment at a psychiatric facility in New Delhi and in 2011 his lawyer requested that the Supreme Court consider his mental condition as grounds for commuting his death sentence. The President of India rejected Devender Pal Singh Bhullar’s mercy petition in May 2011, eight years after the request was filed. -

The Architecture of Democracy

TIF - The Architecture of Democracy PREM CHANDAVARKAR September 4, 2020 Central Vista, New Delhi: The North and South blocks of Rashtrapati Bhavan lit for Republic Day | Namchop (CC BY-SA 3.0) The imperial Central Vista in Delhi has been transformed since 1947 into a symbol of democratic India. But the proposed redevelopment will reduce public space, highlight the spectacle of government and seems to reflect the authoritarian turn in our democracy. The Government of India is proposing a radical reshaping of the architecture and landscape of New Delhi’s Central Vista: a precinct that is the geographical heart of India’s democracy containing Parliament, ministerial offices, the residence and office of the President of India, major cultural institutions, and a public landscape that is beloved to the residents of Delhi and citizens of India. Its design originally came into being in 1913-14 as a British creation meant to mark imperial power in India through a new capital city in Delhi. After Independence, its buildings and spaces have been appropriated by Indians. How was the original design meant to serve as a public symbol of imperial power and governance? In the seven plus decades since Independence, how has it been appropriated by Indians such that during those decades it has Page 1 www.TheIndiaForum.in September 4, 2020 become an integral part of the independent nation’s history, leading to the precinct and its major edifices receiving the highest listing of Grade-1 from the Heritage Conservation Committee, Delhi? And what light does the currently planned redevelopment throw on the direction that contemporary India’s governance is taking, especially in reference to its equation with the general public? To understand these questions in their full depth, we must examine the history of how city form has visually reflected political ideals of governance. -

(CIVIL) NO. 229 of 2020 RAJEEV SURI ...PETITIONER Ve

REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION TRANSFERRED CASE (CIVIL) NO. 229 OF 2020 RAJEEV SURI ...PETITIONER Versus DELHI DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY & ORS. ...RESPONDENTS with TRANSFERRED CASE (CIVIL) NO. 230 OF 2020 CIVIL APPEAL NO. ….…..... OF 2020 (Arising out of S.L.P. (Civil) No. …………./2020) (@ Diary No. 8430/2020) WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 510/2020 WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 638/2020 WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 681/2020 WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 845/2020 WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 853 OF 2020 WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 922/2020 WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 1041/2020 1 J U D G M E N T A.M. Khanwilkar, J. TABLE OF CONTENTS S.NO. TOPIC PARAS 1. Introduction 1 2. Objectives of the Project 2-10 3. Proceedings and Contentions of the 11-123 Parties Consideration 4. Rule of Law 124-135 5. Democratic Due Process and 136-158 Judicial Review 6. Need for Heightened Judicial 159-167 Review 7. Constitutionalism 168-172 8. Participatory Democracy in India 173-198 9. Change in Land Use 199 a) What is Master Plan and Zonal 200-202 Plan. b) Modification of Plans 203-228 c) Procedure before decision 229 d) Procedure during decision- 230-265 making process and Public Hearing under Section 11A e) Quasi Legislative Function 266-273 f) Post change in land use decision 274-275 2 10. CVC Clearance a) Status of CVC and Procedure 276-287 Adopted for Grant of “No Objection” b) Non-application of mind 288-295 c) Legitimate Expectation 296-298 11. DUAC Approval a) Stage for Statutory Approval by 299-306 DUAC b) Arbitrariness in Grant of 307-312 Approval 12. -

Narayani.Pdf

OUR CITY, DELHI Narayani Gupta Illustrated by Mira Deshprabhu Introduction This book is intended to do two things. It seeks to make the child living in Delhi aware of the pleasures of living in a modern city, while at the same time understanding that it is a historic one. It also hopes to make him realize that a citizen has many responsibilities in helping to keep a city beautiful, and these are particularly important in a large crowded city. Most of the chapters include suggestions for activities and it is important that the child should do these as well as read the text. The book is divided into sixteen chapters, so that two chapters can be covered each month, and the course finished easily in a year. It is essential that the whole book should be read, because the chapters are interconnected. They aim to make the child familiar with map-reading, to learn some history without making it mechanical, make him aware of the need to keep the environment clean, and help him to know and love birds, flowers and trees. Our City, Delhi Narayani Gupta Contents Introduction Where Do You Live? The Ten Cities of Delhi All Roads Lead to Delhi Delhi’s River—the Yamuna The Oldest Hills—the Ridge Delhi’s Green Spaces We Also Live in Delhi Our Houses Our Shops Who Governs Delhi? Festivals A Holiday Excursion Delhi in 1385 Delhi in 1835 Delhi in 1955 Before We Say Goodbye 1. Where Do You Live? This is a book about eight children and the town they live in.