The Founding of the Franklin Street Churches A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chapel Hill Methodist Church, a Centennial History, 1853-1953

~bt <lCbaptl 1;111 1Mttbobist €burcb a ~entenntal ,tstOtP, lS53~1953 Qtbe €:bapel i;tll :Metbobigt C!Cbutcb 2l ftentennial ~i6tor!" tS53~1953 By A Committee of the Church Fletcher M. Green, Editor ~bapel ~tll 1954 Contents PREFACE Chapter THE FIRST CHURCH, 1853-1889 By Fletcher M. Green II THE SECOND CHURCH, 1885 -192 0 15 By Mrs. William Whatley Pierson III THE PRESENT CHURCH, 1915-1953 23 By Louis Round Wilson IV WOMEN'S WORK 38 By Mrs.William Whatley Pierson V RELIGIOUS ACTIVITIESOF THE TWENTIETHCENTURY ,------ 52 By Louis Round Wilson and Edgar W. Knight Appendix: LIST OF MINISTERS 65 Compiled by Fletcher M. Green PREFACE Dr. Louis Round Wilson originally suggested the idea of a centennial history of the Chapel Hill Methodist Church in a letter to the pastor, the Reverend Henry G. Ruark, on July 6, 1949. After due consideration the minister appointed a com- mittee to study the matter and to formulate plans for a history. The committee members were Mrs. Hope S. Chamberlain, Fletcher M. Green, Mrs. Guy B. Johnson, Edgar W. Knight, Mrs. Harold G. McCurdy, Mrs. Walter Patten, Mrs. William Whatley Pierson, Mrs. Marvin H. Stacy, and Dr. Louis R. Wilson, chairman. The commilttee adopted a tentative outline and apportioned the work of gathering data among its members. Later Dr. Wilson resigned as chairman and was succeeded by Fletcher M. Green. Others of the group resigned from the committee. Finally, after the data were gathered, Mrs. Pierson, Dr. Green, Dr. Knight, and Dr. Wilson were appointed to write the history. On October 11, 1953, at the centennial cele- bration service Dr. -

Princeton College During the Eighteenth Century

PRINCETON COLLEGE DURING THE Eighteenth Century. BY SAMUEL DAVIES ALEXANDER, AN ALUMNUS. NEW YORK: ANSON D. F. RANDOLPH & COMPANY, 770 Broadway, cor. 9th Street. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1872, by ANSON D. F. RANDOLPH & CO., In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. •^^^ill^«^ %tVYO?^ < I 1 c<\' ' ' lie \)^'\(^tO\.y>^ ^vn^r^ J rjA/\^ \j ^a^^^^ c/^^^^^y^ ^ A^^ 2^^^ ^ >2V^ \3^ TrWxcet INTRODUCTORY NOTE. On account of the many sources from which I have derived my in- formation, and not wishing to burden my page with foot-notes, I have omitted all authorities. 1 have drawn from printed books, from old news- papers and periodicals, and from family records, and when the words of another have suited me, 1 have used them as my own. As Dr. Allen " licensed says, Compilers seem to be pillagers. Like the youth of Sparta, they may lay their hands upon plunder without a crime, if they will but seize it with adroitness." Allen's Biographical Dictionary, Sprague's Annals, and Duyckinck's of American have been of the service Cyclopaedia Literature, greatest ; but in many instances I have gone to the original sources from which they derived their information. I have also used freely the Centennial Discourses of Professors Giger and Cameron of the College. The book does not profess to be a perfect exhibition of the graduates. But it is a beginning that may be carried nearer to perfection in every succeeding year. Its very imperfection may lead to the discovery of new matter, and the correction of errors which must unavoidably be many. -

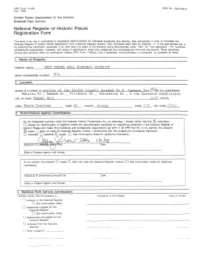

RECEIVED National Park Service

NPS Form 10-900 0024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior RECEIVED National Park Service National Register of Historic Places MAY 3 JQQ/1 Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties SKMt^ the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A)| ( appropr ate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories'and subcategories from the insiri!!cnoTCrPtaicg"aiJiJil onal entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name Old Chapel Hill Cemetery College Graveyard other names/site number 2. Location street & number NW corner N.C. 54 & Country Club Road S not for publication city or town Cha P el Hil1_____________________ _ D vicinity state North Carolina code NC county Orange code 135 Zip code 27599 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this XX nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property S meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant D nationally 3 statewide D locally. (D)See continuation sheet for additional comments.) / ^_________ u Signature of certifying official/title *~{ I ' Date State of Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property D meets D does not meet the National Register criteria. -

NPS Form 10-900 (Oct

1 NPS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. Name of Property Historic name: Old Chapel Hill Cemetery Other name: College Graveyard 2. Location NW corner NC 54 & Country Club Rd, Chapel Hill, NC, 27599 Orange County, Code 135 3. State/Federal Agency Certification Statewide significance 4. National Park Service Certification N/A 5. Classification Ownership of Property: public-local Category of Property: district Number of Resources within Property: 1 noncontributing building, 1 contributing site, 4 contributing and 1 noncontributing structures, 16 contributing and 1 noncontributing objects, 21 contributing and 3 noncontributing total. 6. Function or Use Historic Functions: Funerary/cemetery Current Functions: Funerary/cemetery 7. Description Materials/other: gravemarkers, marble, granite 2 8. Statement of Significance Applicable National Register Criteria A. Property is associated with events that have made a significant contribution to the board patterns of our history. C. Property embodies the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, or method of construction or represents the work of a master, or possesses high artistic values, or represents a significant and distinguishable entity whose components lack individual distinction. Criteria Considerations D. a cemetery Areas of Significance Social History, Ethnic Heritage: black, Other; Funerary Art Period of Significance 1798-1944 Significant Dates 1798 Narrative Statement of Significance Explained on continuation sheets. 9. Major Bibliographic References Primary location of additional data: State Historic Preservation Office 10. Geographical Data Acreage of Property: 6.98 acres UTM References Zone 17 Easting 676650 Northing 3975600 Verbal Boundary Description and Boundary Justification on continuation sheets 11. -

Davidson College

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||| 32101 068568573 DRI N C ETO N UNIVERSITY LIBRARY - º, - - - - -- 5 DAVIDSON COLLEGE Intimate FActs COMPILED BY CORNELIA REBEKAH SHAw Librarian ILLUSTRATED Fleming H. Revel 1 Press NEW YORK Copyright, 1923, by WILLIAM J. MARTIN THIs volume is AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED To THE SoNs of DAVIDson : FOREWORD THE story of the origin and growth of Davidson College, told for the first time in this volume, is typically American. The consecrated idealism of its founders, the bold experimenta tion of its manual-labor infancy, its long and losing battle with poverty and indifference, its rescue by an overruling Providence through the splendid munificence of Maxwell Chambers, the ac cumulating momentum of recent years, its present stability and far-reaching usefulness, its promise for the future—these con stitute a thrilling panorama of divine Providence and human heroism. Its unselfish builders rest from their multiplied la bors, but in endless and ever-increasing beneficence their works do follow them. Our world has learned some startling lessons since the new cen tury began its course. It knows now, as never before, that mere earthly learning, human art and science and inventive genius, the harnessing of nature's giant forces, the production of illimit able wealth and undreamed of luxuries, if these are untouched by religious love and self sacrifice, cannot develop or even pre serve our hard-won civilization; that no gifts are more fatal to human welfare than wealth and leisure without moral culture, liberty without self-control, and unlimited power without jus tice or mercy; that in this age of revolution and reconstruction Christian leadership is the one and only hope of imperiled and bewildered Christendom. -

College Libraries in North Carolina from 1795 to the Civil War

0 Books in Tolerable Supply: College Libraries in North Carolina from 1795 to the Civil War orth Carolina Libraries Volume 65, Number 3/4, pp. 62-69 http://www.nclaonline.org/NCL/ncl/NCL_65_3-4_Fall-Winter2007.pdf Patrick M. Valentine, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Library Science and Instructional Technology East Carolina University [email protected] Mailing address: 3001 Landrum Drive, Wilson, N.C. 27896-1260 Home phone 252/291-4864 I guarantee that the work is original, it has not been previously published, and it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere in any form. Patrick M. Valentine 1 Books in Tolerable Supply: College Libraries in North Carolina from 1795 to the Civil War Abstract: The historical role of college libraries has seldom been investigated on a regional or state level in the United States, but such studies are valuable in explaining the cultural infrastructure of education and print culture. State and regional studies also set the context for further research on individual libraries and colleges as well as histories on a larger level. This work examines how college libraries developed in orth Carolina from 1800 to 1860 and illustrates the growth and ambience of education and print culture during a formative period of the antebellum South. 2 Books in Tolerable Supply: College Libraries in North Carolina from 1795 to the Civil War A “professor in a College who is without books in tolerable supply, is analogous to the creation of nobility which for want of estate is obliged to live in rags.” Joseph Caldwell, Letter, 19 February 1824 1 A number of southern colleges and universities trace their founding back to pre-Civil War times, yet historians have rarely studied their libraries. -

Street & Number a Nortion of the Blocks Roughl V Botmded Bv H. Cameron

NPS Form I 0-900 OMS No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990: United States Department of the Interior National Park Service This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Comolete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions. architectural classification. materials. and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter. word processor. or computer. to complete all items. historic name ____:~.,:,.!:~'"E=S=T'----""'CH= .....=A..P::....::EL=-....::.HI=LL=-=hJ:=S==-T=O=R=I"-"C::..____.:::D:...:I=S-=TR=l =-IC"""'T=----------------- other names/site number _N_/A ______________________________ _ street & number a nortion of the blocks roughlv botmded bv H. Cameron Ave l~jl~bt for publication t·'!alette St., Ransom St., Pittsboro St., University Dr., & the ~~est\vood Subdivision city or town Chapel Hill N ;_K) vicinity state North Carolina code _NC__ county ____,O""""r....,a...... n.....,_,g .....e~------ code _13_5_ zip code 2 7 51 I.J. State of Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property 0 meets 0 does not meet the National Register criteria. ( 0 See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of commenting offic1ai!Title Date State or Federal agency and bureau 4. -

Innovation @ Carolina

Innovation @ Carolina Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Te University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Background and Sample of Current Activities A Working Report Version 1.0, December 22, 2009 Authors: Maryann Feldman, Judith Cone, Mark Meares, Lowry Caudill, Jennifer Miller, Lauren Lanahan, and Gil Avnimelech P REPARED FOR THE INNOVAT I O N CIRCL E CON V ENED B Y CHANCELLOR HOLDEN THO RP, JANUARY 2010 Membership as of December 23, 2009 University of Utah TractManager Salt Lake City, Utah Saddle Brook, New Jersey The Chancellor’s Innovation Circle Jason Kilar CEO, Hulu LLC Christy Shaffer Seattle, Washington CEO, Inspire Rye Barcott Dennis Gillings Pharmaceuticals Founder, Carolina Chairman, CEO, Richard Krasno Chapel Hill, North Carolina for Kibera Quintiles Transnational Executive Director, Charlotte, North Carolina Corporation William R. Kenan, Jr. Sallie Shuping-Russell Durham, North Carolina Charitable Trust; Managing Director, Harris Scott Barton Trustee, Kenan Institute Blackrock Alternative Managing Director, Julia Sprunt Grumbles of Private Enterprise Advisors Capital Dynamics Vice President, Turner Chapel Hill, North Carolina Chapel Hill, North Carolina Palo Alto, California Broadcasting (Retired) Chapel Hill, North Carolina Myla Lai-Goldman M.D. Richard Stack Vaughn Bryson Scientific Advisor, Director, Founder, President, CEO Reginald Lee Seventh Sense President, Synecor LLC Eli Lilly & Co. (Retired) (Reg) Hardy Biosystems, Inc. Chapel Hill, North Carolina President, Managing Director, Cambridge, Massachusetts Clinical Products, Ltd. C/Max Capital Corporation William (Bill) N. Starling Vero Beach, Florida Fort Lauderdale, Florida Doug Mackenzie Managing Director, Founder, Partner, Radar; Synergy Life Science W. Lowry Caudill F. Neal Hunter Affiliated Partner at Partners; CEO, Synecor LLC Chair, Co-founder, Co-Founder, Executive Kleiner, Perkins, Portola Valley, California Magellan Laboratories, Chair, Cree, Inc. -

The First Presbyterian Church, Asheville, N.C., 1794-1951

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/firstpresbyteriaOOmcco Copyright 1951 by The First Presbyterian Church Asheville, N. C. THE MILLER PRINTING COMPANY, ASHEVILLE, N. C. THE FIRST RESBYTERIAN ChURCH ASHEVILLE, N. C. 1794-1951 by George W. McCoy Published 1951 by The First Presbyterian Church Asheville, North Carolina ovitevits CHAPTER I The Coming o£ the Scotch-Irish 1 CHAPTER II The Rev. George Newton 4 CHAPTER III Early Struggles 13 CHAPTER IV Period of Transition 17 CHAPTER V First Building on Church Street 20 CHAPTER VI Old and New Schools 23 CHAPTER VII The War Period 30 CHAPTER VIII Second Building on Church Street 35 CHAPTER IX The Rev. Robert F. Campbell, D. D 40 CHAPTER X Years of Growth 44 CHAPTER XI The Rev. C. Grier Davis, D. D 54 CHAPTER XII Physical Improvements 60 ustiratiovis First Presbyterian Church in 1951 Frontispiece Church as shown in sketch of Asheville in 1851 20 The Rev. William A. Wood, D. D 32 The Rev. William B. Corbett 32 The Rev. James K. P. Gammon 32 The Rev. William S. P. Bryan, D. D 32 Sanctuary after remodeling in 1890 38 The First Presbyterian Church in 1899 44 The Rev. Robert Fishburne Campbell, D. D 50 The Rev. Calvin Grier Davis, D. D 56 Sanctuary in 1951 62 VI ^CHRONOLOGY OF MINISTERS The Rev. George Newton 1797-1814 The Rev. Francis H. Porter 1817-1823 The Rev. James McRee, D. D 1825 The Rev. A. D. Metcalf 1825 The Rev John Silliman 1828 The Rev. Robert H. Chapman, D. -

The Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies' Contributions to The

The Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies' Contributions to the Library of the University of North Carolina, 1886-1906 [North Carolina Historical Review, Volume LIX, Number 4, October 1982, pages 327-353.] Maurice C. York* Cornelia Phillips Spencer, avid supporter of the University of North Carolina and habitual epistler, proclaimed in the North Carolina Presbyterian in the summer of 1886 that she was as "proud as a peacock" about the substantial improvement in the quality of the university library housed at Smith Hall: That fine hall, what have I not seen in it, lo! these many years? Everything except books. It was the ballroom for the State. We had theatrical performances in it. We had private dances there--public entertainments. The University Normal Schools used it for kindergartens. "Walkarounds," elocutionary displays--what not? Now in the year '86, for the first time, I see it a library.1[1] The Dialectic and philanthropic literary societies functioned as catalysts in a reaction that transformed the library of the University of North Carolina from small, poorly selected, and virtually inaccessible collection into a resource more responsive to campus needs. In 1886th e students merged their extensive libraries with the university's books in Smith Hall. During the following two decades, the members of the societies worked closely with the faculty to increase the size of the collection and to administer the library more effectively so that by 1906 the facility assumed a position of respect among southern state university libraries. Interaction among the university and the societies did not begin in 1886, for the growth of the student groups paralleled the development of their parent. -

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library and the Sciences, 1795-1902

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library and the Sciences, 1795-1902 by William R. Burk arly in the history of the University faculty, particularly the scientists, were developing Henry Horace Williams, librarian, sets 1881-83 of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, stronger interests in research. It became important up residency in Smith Hall three library collections developed: for them to have access to collections containing Total number of volumes, 9,000; the University Library and the libraries of the current books for research and education. They 1884 pamphlets, 2,000 Euniversity’s literary societies (the Dialectic and the also, with increasing frequency, required students Joseph A. Holmes book collection Philanthropic societies, informally known as the to consult literature outside the classroom, and the 1886 Di and the Phi). The university collection was not library became the center of the university. This approved for purchase diverse. It emphasized the classics and theology, paper highlights the University Library’s general Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies libraries (about 15,000 volumes) reflecting a curriculum strong in ancient languages, history and development; it chronicles the rise and 1886 mathematics, natural philosophy, chemistry, and expansion of the scientific and medical collections moved to Smith Hall, but maintained moral philosophy1 and weak in general literature. as well as the origin of departmental science as distinct collections Student use of the library was infrequent, due in part libraries, with particular emphasis on the biology Library becomes “heart of the 1890s to the fact that the favored method of instruction library. Coverage concludes with the establishment University”a at the university was based on recitations and of the Graduate School in 1903 and the subsequent Dialectic and Philanthropic Societies textbooks and not on outside reading and library rise of research at UNC. -

Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960

BLACK FREEDOM AND THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, 1793-1960 JOHN K. CHAPMAN A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by: James L. Leloudis Jerma A. Jackson Reginald Hildebrand Gerald Horne Timothy B. Tyson ” 2006 JOHN K. CHAPMAN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JOHN K. CHAPMAN: Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1793-1960 (Under the direction of James L. Leloudis) Recent histories of the University of North Carolina trivialize the institution’s support for white supremacy during slavery, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow, while denying that this unjust past affects the university today. The celebratory lens also filters out African American contributions to the university. In fact, most credit for UNC’s increased diversity is due to the struggles of African Americans and other traditionally disenfranchised groups for equal rights. During both the 1860s and the1960s, black freedom movements promoted norms of democratic citizenship and institutional responsibility that challenged the university to become more honest, more inclusive, and more just. By censoring this historical viewpoint, previous scholarship has contributed to a culture of denial and racial historical amnesia that heralds UNC as the “University of the People,” without seriously engaging questions of justice in the past or the present. This dissertation demonstrates that before 1865, the gentry used the university to promote the growth of slavery. Following Emancipation, university trustees led the white supremacy campaign to suppress black freedom and Radical Reconstruction.