Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina at the Local Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

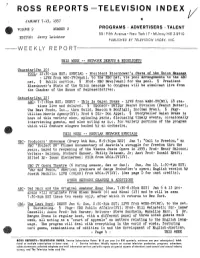

Ross Reports -Television Index

ROSS REPORTS -TELEVISION INDEX JANUARY 7-13, 1957 VOLUME NUMBER 2 PROGRAMS ADVERTISERS TALENT 551 Fifth Avenue New York 17 MUrray Hill 2-5910 EDITOR: Jerry Leichter PUBLISHED BY TELEVISION INDEX, INC. WEEKLY REPORT THIS WEEK -- NETWORK DEBUTS & HIGRT.TGHTS Thursday(Jan 10) POOL- 12:30-1pm EST; SPECIAL - President Eisenhower's State of the Union Message - LIVE fromWRC-TV(Wash), to the NBC net, via pool arrangements to the ABC net. § Public service. § Prod- NBC News(Wash) for the pool. § President Eisenhower's State of the Union message to Congress will be simulcast live from the Chamber of the House of Representatives. Saturday(Jan 12) ABC- 7-7:30pm EST; DEBUT - This Is Galen Drake - LIVE fromWABC-TV(NY), 18 sta- tions live and delayed. § Sponsor- Skippy Peanut Division (Peanut Butter), The Beet Foods, Inc., thru Guild, Bascom & Bonfigli,Inc(San Fran). § Pkgr- William Morris Agency(NY); Prod & Dir- Don Appel. § Storyteller Galen Drake is host of this variety show, spinning yarns, discussing timely events, occasionally interviewing guests, and also acting as m.c. for variety portions of the program which will feature singers backed by an orchestra. THIS WEEK -- REGULAR NETWORK SPECIALS NBC- Producers' Showcase (Every 4th Mon,8-9:30pmEST) Jan 7; "Call to Freedom," an NBC 'Project 20' filmed documentary of Austria's struggle for freedom thruthe years, keyed to reopening of the Vienna State Operain 1955; Pod- Henry Salomon; Writers- Salomon, Richard Hanser, Philip Reisman, Jr; Asst Prod- Donald Hyatt; Edited By- Isaac Kleinerman; FILM from WRCA-TV(NY). NBC TV Opera Theatre (6 during season, Sat orSun); Sun, Jan 13, 1:30-4pm EST; "War and Peace," American premiere of Serge Prokofiev's opera; English version by Joseph Machlis; LIVE (COLOR) from WRCA-TV(NY). -

Mccorkle PLACE

CHAPTER EIGHT: McCORKLE PLACE McCorkle Place is said to be the most densely memorialized piece of real estate in North Carolina.501 On the University’s symbolic front lawn, there are almost a dozen monuments and memorials fundamental to the University’s lore and traditions, but only two monuments within the space have determined the role of McCorkle Place as a space for racial justice movements.502 The Unsung Founders Memorial and the University’s Confederate Monument were erected on the oldest quad of the campus almost a century apart for dramatically different memorial purposes. The former honors the enslaved and freed Black persons who “helped build” the University, while the latter commemorated, until its toppling in August 2018, “the sons of the University who entered the war of 1861-65.”503 Separated by only a few dozen yards, the physical distinctions between the two monuments were, before the Confederate Monument was toppled, quite striking. The Unsung 501 Johnathan Michels, “Who Gets to be Remembered In Chapel Hill?,” Scalawag Magazine, 8 October 2016, <https://www.scalawagmagazine.org/2016/10/whats-in-a-name/>. 502 Timothy J. McMillan, “Remembering Forgetting: A Monument to Erasure at the University of North Carolina,” in Silence, Screen and Spectacle: Rethinking Social Memory in the Age of Information, ed. Lindsay A. Freeman, Benjamin Nienass, and Rachel Daniell, 137-162, (Berghahn Book: New York, New York, 2004): 139-142; Other memorials and sites of memory within McCorkle Place include the Old Well, the Davie Poplar, Old East, the Caldwell Monument, a Memorial to Founding Trustees, and the Speaker Ban Monument. -

Perkins, Anthony (1932-1992) by Tina Gianoulis

Perkins, Anthony (1932-1992) by Tina Gianoulis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2007 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The life and career of actor Anthony Perkins seems almost like a movie script from the times in which he lived. One of the dark, vulnerable anti-heroes who gained popularity during Hollywood's "post-golden" era, Perkins began his career as a teen heartthrob and ended it unable to escape the role of villain. In his personal life, he often seemed as tortured as the troubled characters he played on film, hiding--and perhaps despising--his true nature while desperately seeking happiness and "normality." Perkins was born on April 4, 1932 in New York City, the only child of actor Osgood Perkins and Janet Esseltyn Rane. His father died when he was only five, and Perkins was reared by his strong-willed and possibly abusive mother. He followed his father into the theater, joining Actors Equity at the age of fifteen and working backstage until he got his first acting roles in summer stock productions of popular plays like Junior Miss and My Sister Eileen. He continued to hone his acting skills while attending Rollins College in Florida, performing in such classics as Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest. Perkins was an unhappy young man, and the theater provided escape from his loneliness and depression. "There was nothing about me I wanted to be," he told Mark Goodman in a People Weekly interview. "But I felt happy being somebody else." During his late teens, Perkins went to Hollywood and landed his first film role in the 1953 George Cukor production, The Actress, in which he appeared with Spencer Tracy. -

31 Days of Oscar® 2010 Schedule

31 DAYS OF OSCAR® 2010 SCHEDULE Monday, February 1 6:00 AM Only When I Laugh (’81) (Kevin Bacon, James Coco) 8:15 AM Man of La Mancha (’72) (James Coco, Harry Andrews) 10:30 AM 55 Days at Peking (’63) (Harry Andrews, Flora Robson) 1:30 PM Saratoga Trunk (’45) (Flora Robson, Jerry Austin) 4:00 PM The Adventures of Don Juan (’48) (Jerry Austin, Viveca Lindfors) 6:00 PM The Way We Were (’73) (Viveca Lindfors, Barbra Streisand) 8:00 PM Funny Girl (’68) (Barbra Streisand, Omar Sharif) 11:00 PM Lawrence of Arabia (’62) (Omar Sharif, Peter O’Toole) 3:00 AM Becket (’64) (Peter O’Toole, Martita Hunt) 5:30 AM Great Expectations (’46) (Martita Hunt, John Mills) Tuesday, February 2 7:30 AM Tunes of Glory (’60) (John Mills, John Fraser) 9:30 AM The Dam Busters (’55) (John Fraser, Laurence Naismith) 11:30 AM Mogambo (’53) (Laurence Naismith, Clark Gable) 1:30 PM Test Pilot (’38) (Clark Gable, Mary Howard) 3:30 PM Billy the Kid (’41) (Mary Howard, Henry O’Neill) 5:15 PM Mr. Dodd Takes the Air (’37) (Henry O’Neill, Frank McHugh) 6:45 PM One Way Passage (’32) (Frank McHugh, William Powell) 8:00 PM The Thin Man (’34) (William Powell, Myrna Loy) 10:00 PM The Best Years of Our Lives (’46) (Myrna Loy, Fredric March) 1:00 AM Inherit the Wind (’60) (Fredric March, Noah Beery, Jr.) 3:15 AM Sergeant York (’41) (Noah Beery, Jr., Walter Brennan) 5:30 AM These Three (’36) (Walter Brennan, Marcia Mae Jones) Wednesday, February 3 7:15 AM The Champ (’31) (Marcia Mae Jones, Walter Beery) 8:45 AM Viva Villa! (’34) (Walter Beery, Donald Cook) 10:45 AM The Pubic Enemy -

Tarheel Junior Historian

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association Carolina's Mountain Region History Journal For Inquiring Students A Fall 197 tar heel junior historian Gltaitel Gltallie's QltaU The Tar Heel Junior Historian Association is making history this year by celebrating its twenty-fifth anniversary. Special plans are being made for the "biggest and best" Awards Day ever. It will be held at Meredith College in Raleigh on May 18 and 19. You can start now by making a placard on poster board paper with Placard means a notice, your club name on it. This placard should be 14 inches high usually displayed on by 22 inches wide. Use your imagination to draw a design a sign or poster. that represents either your club or the historical events associated with your community. Prizes will be given for outstanding ones. Also, newly designed membership cards and special Tar Heel Junior Historian recruiting posters will soon be sent to you. Use them to help us recruit new members in this special anniversary year! Visual history is both an exciting detective game and a learning experience for junior historians. Service to the community is its own reward. Junior historians have put many thousands of hours into such work and have received national recognition for their efforts. To help you to plan for the coming Awards Day and to remind you of all the activities of last May, be sure to read the article "Awards Day 1977" in this issue. In that article, please pay particular attention to the ideas for Recruit means to get or enlist. -

John Randolph Haynes Papers, Circa 1873-1960S LSC.1241

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf558006bd No online items Finding Aid for the John Randolph Haynes papers, circa 1873-1960s LSC.1241 Finding aid prepared by Simon Elliott with assistance from Brittany Sprigg and Bernadette Roca; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala, 2004. Additional processing by Kelly Besser with assistance from Kuhelika Ghosh and Krystell Jimenez, 2018. Machine-readable finding aid revised and updated by Kelly Besser, 2018. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] Online finding aid last updated 2018 May 5. Finding Aid for the John Randolph LSC.1241 1 Haynes papers, circa 1873-1960s LSC.1241 Title: John Randolph Haynes papers Identifier/Call Number: LSC.1241 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 351.0 linear feet(358 boxes, 106 oversize flat boxes, 36 cartons, and 15 map folders) Date (bulk): Bulk, 1890-1937 Date (inclusive): circa 1873-1960s Abstract: John Randolph Haynes was an active reformer and member of the Progressive movement. His wife, Dora Haynes was a suffragist, leading the campaign for women’s right to vote in California. Together, they founded The John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation in 1926. The collection primarily consists of manuscripts, maps, correspondence, minutes, notes, newspaper clippings, photographs, reports, speeches, scrapbooks, ephemera, and other printed materials related to John Randolph Haynes’ involvement with local and regional planning in Southern California and a variety of social and political issues. -

Of the Rotary Club of Charlotte 1916-1991

Annals of the Rotary Club of Charlotte 1916-1991 PRESIDENTS RoGERS W. DAvis . .• ........ .. 1916-1918 J. ConDON CHRISTIAN, Jn .......... 1954-1955 DAVID CLARK ....... .. •..• ..... 191 8-1919 ALBERT L. BECHTOLD ........... 1955-1956 JoHN W . Fox ........•.. • ....... 1919-1920 GLENN E. P ARK . .... ......•..... 1956-1957 J. PERRIN QuARLES . ..... ...•... .. 1920-1921 MARSHALL E. LAKE .......•.. ... 1957-1958 LEwis C. BunwELL ...•..•....... 1921-1922 FRANCIS J. BEATTY . ....•. .... ... 1958-1959 J. NoRMAN PEASE . ............. 1922-1923 CHARLES A. HuNTER ... •. .•...... 1959-1960 HowARD M. \ VADE .... .. .. .• ... 1923-1924 EDGAR A. TERRELL, J R ........•.... 1960-1961 J. Wl\1. THOMPSON, Jn . .. .... .. 1924-1925 F. SADLER LovE ... .. ......•...... 1961-1962 HAMILTON C. JoNEs ....... ... .... 1925-1926 M. D . WHISNANT .. .. .. • .. •... 1962-1963 HAMILTON W . McKAY ......... .. 1926-1 927 H . HAYNES BAIRD .... .. •.... .. 1963-1964 HENRY C. McADEN ...... ..•. ... 1927- 1928 TEBEE P. HAWKINS .. ....•. ... 1964-1965 RALSTON M . PouND, Sn. .• . .... 1928- 1929 }AMES R. BRYANT, JR .....•.. •..... 1965-1966 J oHN PAuL LucAs, Sn . ... ... ... 1929-1 930 CHARLES N. BRILEY ......•..•. ... 1966-1967 JuLIAN S. MILLER .......•... .•. .. 1930-193 1 R. ZAcH THOMAS, Jn • . ............ 1967-1968 GEORGE M. lvEY, SR ..... ..... .. 1931-1932 C. GEORGE HENDERSON ... • ..•.. 1968- 1969 EDGAR A. TERRELL, Sn...•........ 1932-1 933 J . FRANK TIMBERLAKE .......... 1969-1970 JuNIUS M . SMITH .......•. ....... 1933-1934 BERTRAM c. FINCH ......•.... ... 1970-1971 }AMES H. VAN NESS ..... • .. .. .. 1934-1935 BARRY G. MILLER .....• ... • .... 1971-1972 RuFus M. J oHNSTON . .•..... .. .. 1935-1936 G. DoN DAviDsoN .......•..•.... 1972-1973 J. A. MAYO "" "."" " .""" .1936-1937 WARNER L. HALL .... ............ 1973-1974 v. K. HART ... ..•.. •. .. • . .•.... 193 7- 1938 MARVIN N. LYMBERIS .. .. •. .... 1974-1975 L. G . OsBORNE .. ..........•.... 1938-1939 THOMAS J. GARRETT, Jn........... 1975-1976 CHARLES H. STONE . ......•.. .... 1939-1940 STUART R. DEWITT ....... •... .. 1976-1977 pAUL R. -

(CHARLES HOLMES), 1867-1938. Charles H. Herty Papers, 1860-1938

HERTY, CHARLES H. (CHARLES HOLMES), 1867-1938. Charles H. Herty papers, 1860-1938 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Herty, Charles H. (Charles Holmes), 1867-1938. Title: Charles H. Herty papers, 1860-1938 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 8 Extent: 73.5 linear feet (147 boxes), 3 bound volumes (BV), and 1 oversized papers box and 2 oversized papers folders (OP) Abstract: Personal and professional papers of Georgia chemist Charles Holmes Herty, including correspondence, financial and legal records, manuscripts, notes, photographs, clippings and copies of articles and speeches dealing with Herty's research and interests, records of his work with professional organizations, and family photographs and memorabilia. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Source Gift, 1957, with subsequent additions. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Charles H. Herty papers, 1860-1938 Manuscript Collection No. 8 Citation [after identification of item(s)], Charles H. Herty papers, Stuart A. -

Onetouch 4.6 Scanned Documents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1. Native Empires in the Old Southwest . 20 2. Early Native Settlers in the Southwest . 48 3. Anglo-American Settlers in the Southwest . 76 4. Early Federal Removal Policies . 110 5. Removal Policies in Practice Before 1830 . 140 6. The Federal Indian Commission and the U.S. Dragoons in Indian Territory . .181 7. A Commission Incomplete: The Treaty of Camp Holmes . 236 8. Trading Information: The Chouteau Brothers and Native Diplomacy . 263 Introduction !2 “We presume that our strength and their weakness is now so visible, that they must see we have only to shut our hand to crush them” - Thomas Jefferson to William Henry Harrison, February 27, 1803 Colonel Henry Dodge of the U.S. dragoons waited nervously at the bottom of a high bluff on the plains of what is now southwestern Oklahoma. A Comanche man on a white horse was barreling down the bluff toward Dodge and the remnants of the dragoon company that stood waiting with him. For weeks the dragoons had been wandering around the southern plains, hoping to meet the Comanches and impress them with the United States’ military might. However, almost immediately after the dragoon company of 500 men had departed from Fort Gibson in June 1834, they were plagued by a feverish illness and suffered from the lack of adequate provisions and potable water. When General Henry Leavenworth, the group’s leader, was taken ill near the Washita River, Dodge took command, pressing forward in the July heat with about one-fifth of the original force. The Comanche man riding swiftly toward Dodge was part of a larger group that the dragoons had spotted earlier on the hot July day. -

Planter Reaction in North Carolina to Presidential Reconstruction, 1865-1867

The Woman's College of The University of North Carolina LIBRARY no.5H5 COLLEGE COLLECTION Gift of Kenneth Jay Miller PLANTER REACTION IN NORTH CAROLINA TO PRESIDENTIAL RECONSTRUCTION, 1865-1867 by Kenneth Jay Miller A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts . >6 Greensboro July, 1964 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Thesis ^ Director ^ , __A^vt-^<"f Oral Examination Committee Members fad?**/ ^Mf'&W '(]K /yu v ■■fl-'/]&i/tXjL^ "Z-<si-t-/*' /s)*-^i~*J-*~ & 270333 Date of Examination MILLER, KENNETH JAY. Planter Reaction in North Carolina to Presidential Reconstruction, 1865-1867. (1964) Directed by: Dr. James S. Ferguson. PP« 92. When the Civil iar ended, the planter faced many- problems. The physical and economic destruction to the South had necessitated rebuilding. The capital with which to accomplish tnis had either been destroyed or had fled the region. In addition, the labor base of the region— slavery—had been eradicated. These were the major pro- blems which confronted the planter. Although North Carolina planters had differences, their enthusiastic support of Henry Clay they had in com- mon. Most of tiem had been Unionists during the seces- sion controversy. Under Presidential Reconstruction, Provisional Governor William if. Holden called a convention which met and outlawed the secession ordinance, abolished slavery, and cancelled the war debt. There was little disagreement among planters on the first two issues, but they did not relish repudiation. -

Kenneth Raper, Elisha Mitchell And<Emphasis Type="Italic

Perspectives Kenneth Raper, Elisha Mitchell and Dictyostelium EUGENE R KATZ Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794, USA (Email, [email protected]) 1. Introduction forms the fruiting body. The fruiting body, a small plant-like structure about a millimetre tall, basically consists of only Dictyostelium discoideum has become an important organism two kinds of cells, stalk cells in the stalk and spore cells con- in the study of modern cellular and developmental tained in a droplet of liquid above the stalk. Although mod- biology (Kessin 2001). The most recent International ern work has shown that there are several cellular subtypes, Dictyostelium Conference, held outside Grenoble, France Raper’s view was essentially correct. Furthermore, under a last summer, was attended by more than 150 scientists from given set of nutritional and environmental conditions, the thirteen countries. D. discoideum is a member of a group of ratio of spore cells to stalk cells in the fruiting body is fixed, organisms known as the cellular slime moulds. Cellular with spores representing about 80% of the cells and stalk slime moulds were first described in the second half of cells 20%. Since both spore cells and stalk cells derive from the nineteenth century but their potential as model organisms amoebae, Raper was interested in understanding how the only began to be appreciated with the isolation of the amoebae made the decision about which of the two cell types D. discoideum species by Kenneth Raper in 1933. Raper was, to become. He thought it could be a model for how cell fate at the time, working for the United States Department of decisions are made during the embryogenesis of higher Agriculture as a mycologist. -

Hastings Community (Fall 1991) Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association

UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Hastings Alumni Publications 9-1-1991 Hastings Community (Fall 1991) Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/alumni_mag Recommended Citation Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association, "Hastings Community (Fall 1991)" (1991). Hastings Alumni Publications. 78. http://repository.uchastings.edu/alumni_mag/78 This is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Alumni Publications by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. IN al IN, HASTINGS- CAMPUS NEWS FACULTY NEWS AND NOTES ALUMNI NEWS 13 18 Exploring Ideas for New Curriculum 'Rugby Team' isAlive and Winning Academic Dean Mary Kay Kane talks about The regular team the College once fielded may be ways in which Hastings is moving ahead in gone, but alumni stalwarts are making sure 1 broadening its curricular offerings and discusses Hastings' rugby wont soon be forgotten as an questions that deserve further exploration in the alumni group calling itself the "Hastings Old Boys' A New Class, A Big Welcome broader alumni community. takes top honors at the prestigious Santa Barbara Rugby Tournament. Students in the Class of 1994 arrive from forty states and seven nations, receiving a summer-long welcome 14 from alumni, faculty, staff, and fellow students. "You are here, each of you, to become great Hastings' New Faculty lawyers," Dean Tom Read tells them. "We welcome The five new professors who arrived on campus this you with great enthusiasm." fall are introduced to the Hastings alumni family - with a brief outline of the diverse scholarship they 7 bring to current students.