EUROPE-AFRICA QUALITY CONNECT: Building Institutional Capacity Through Partnership PROJECT RESULTS and FUTURE PROSPECTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REPORT – 10Th February 2021 REMOTE LEARNING for SUSTAINABLE EQUITY & ACCESS in HIGHER EDUCATION

ONLINE VIDEO MEETING REPORT – 10th February 2021 REMOTE LEARNING FOR SUSTAINABLE EQUITY & ACCESS IN HIGHER EDUCATION GOLA! #LEARNINGMUSTNEVERSTOP GOLA Report Contents Section 1. Format & Participants 1.1 Introduction 04 1.2 Executive Summary & Key Findings of the Meeting 04 1.3 Format of Video Conference & this Report 06 1.4 Participants 07 Section 2. Discussion 2.1 Opening Statements 11 2.2 Lessons, Challenges and Responses to Covid 13 2.3 Connectivity and the ICT Infrastructure 16 2.4 Online & Blended Learning, Systems and Pedagogy 17 2.5 Assessment Concerns, Collaboration and Policy 20 2.6 Closing Q & A with Sir Steve Smith 23 Section 3. Appendices 3.1 Appendix A: Prof Yakubu Ochefu Presentation 27 3.2 Appendix B: Prof Cheryl Foxcroft Presentation 38 3.3 Appendix B: Kortext Presentation 49 02 Glo v FORMAT & PARTICIPANTS SECTION Format & 1. Participants 1.1 Introduction The purpose of this private video meeting for university vice chancellors and senior leadership officers from Africa, organised in partnership with Kortext, was to discuss the best approaches to enabling remote learning for students in higher education. Participants were encouraged to discuss the actions and policies of their universities, and to make recommendations where appropriate. whilst improving the digital skills development of teachers? In response to the Covid pandemic, many officials Is there now an opportunity for universities to have spoken of the challenges of remote learning in collaborate as purchasing consortia to gain better Africa, with need for a far more robust infrastructure value from the edtech and content providers? and more competitive pricing for the usage of data. -

Managing Change at Universities. Volume

Frank Schröder (Hg.) Schröder Frank Managing Change at Universities Volume III edited by Bassey Edem Antia, Peter Mayer, Marc Wilde 4 Higher Education in Africa and Southeast Asia Managing Change at Universities Volume III edited by Bassey Edem Antia, Peter Mayer, Marc Wilde Managing Change at Universities Volume III edited by Bassey Edem Antia, Peter Mayer, Marc Wilde SUPPORTED BY Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences, 2019 Terms of use: Postfach 1940, 49009 Osnabrück This document is made available under a CC BY Licence (Attribution). For more Information see: www.hs-osnabrueck.de https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 www.international-deans-course.org [email protected] Concept: wbv Media GmbH & Co. KG, Bielefeld wbv.de Printed in Germany Cover: istockphoto/Pavel_R Order number: 6004703 ISBN: 978-3-7639-6033-0 (Print) DOI: 10.3278/6004703w Inhalt Preface ............................................................. 7 Marc Wilde and Tobias Wolf Innovative, Dynamic and Cooperative – 10 years of the International Deans’ Course Africa/Southeast Asia .......................................... 9 Bassey E. Antia The International Deans’ Course (Africa): Responding to the Challenges and Opportunities of Expansion in the African University Landscape ............. 17 Bello Mukhtar Developing a Research Management Strategy for the Faculty of Engineering, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria ................................. 31 Johnny Ogunji Developing Sustainable Research Structure and Culture in Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu Alike Ebonyi State Nigeria ....................... 47 Joseph Sungau A Strategy to Promote Research and Consultancy Assignments in the Faculty .. 59 Enitome Bafor Introduction of an annual research day program in the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Benin, Nigeria ........................................... 79 Gratien G. Atindogbe Research management in Cameroon Higher Education: Data sharing and reuse as an asset to quality assurance ................................... -

RETHINKING AFRICAN PARTNERSHIPS for GLOBAL SOLUTIONS © Michigan State University RETHINKING AFRICAN PARTNERSHIPS for GLOBAL SOLUTIONS

RETHINKING AFRICAN PARTNERSHIPS for GLOBAL SOLUTIONS © Michigan State University RETHINKING AFRICAN PARTNERSHIPS for GLOBAL SOLUTIONS EDITORS AND CONTRIBUTORS AMY JAMISON RICHARD MKANDAWIRE Coordinator, Alliance for African Partnership Director, Alliance for African Partnership Secretariat Michigan State University Michigan State University THOMAS JAYNE JAMIE MONSON Co-Director, Alliance for African Partnership; Co-Director, Alliance for African Partnership; University Foundation Professor of Agriculture Director, African Studies Center and Food Resource Economics Michigan State University Michigan State University ISAAC MINDE Coordinator, Alliance for African Partnership Michigan State University CONTRIBUTORS THELMA AWORI ADIPALA EKWAMU Chair Emeritus, Founding Chair and President Executive Secretary Sustainable Market Women’s Fund Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM) SOSTEN CHIOTHA Regional Director PENINA MLAMA Leadership for Environment and Development (LEAD) Professor, Creative Arts Department and Mwalimu Nyerere Southern and Eastern Africa Professorial Chair in Pan-African Studies University of Dar es Salaam CHINWE EFFIONG Assistant Dean, The MasterCard Foundation Scholars MOSES OSIRU Program and Youth Empowerment Programs Deputy Executive Director Michigan State University Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM) DAVE EKEPU Intern DAVID WILEY Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building Professor Emeritus, Department of Sociology in Agriculture (RUFORUM) Director Emeritus, African Studies Center Michigan State University Rethinking African Partnerships for Global Solutions 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This edited volume is published by Michigan State University’s Alliance for African Partnership, and is the product of numerous discussions in 2016 and 2017 with colleagues in African universities, research institutes, governments, private sector organizations and civil society, as well as with strategic development partners and MSU’s Africanist faculty. -

Diversion As a Gratification Factor Influencing Mobile Phone Technology Use by Public University Students in Nairobi, Kenya

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 11, 2020, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2020 HRMARS Diversion as a Gratification Factor Influencing Mobile Phone Technology Use by Public University Students in Nairobi, Kenya Onyango Christopher Wasiaya, Sikolia Geoffrey Serede, Mberia Hellen Kinoti To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i11/7787 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i11/7787 Received: 01 September 2020, Revised: 24 September 2020, Accepted: 16 October 2020 Published Online: 11 November 2020 In-Text Citation: (Wasiaya, Serede, & Kinoti, 2020) To Cite this Article: Wasiaya, O. C., Serede, S. G., & Kinoti, M. H. (2020). Diversion as a Gratification Factor Influencing Mobile Phone Technology Use by Public University Students in Nairobi, Kenya. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences. 10(11), 141-155. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 10, No. 11, 2020, Pg. 141-155 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 141 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. -

Admission and Graduation Statistics.Pdf

TANZANIA COMMISSION FOR UNIVERSITIES HIGHER EDUCATION STUDENTS ADMISSION, ENROLMENT AND GRADUATION STATISTICS 2012/13 - 2017/18 ΞdĂŶnjĂŶŝĂŽŵŵŝƐƐŝŽŶĨŽƌhŶŝǀĞƌƐŝƟĞƐ;dhͿ͕ϮϬϭϴ W͘K͘ŽdžϲϱϲϮ͕ĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ͕dĂŶnjĂŶŝĂ dĞů͘нϮϱϱͲϮϮͲϮϭϭϯϲϵϰ͖&ĂdžнϮϱϱͲϮϮͲϮϭϭϯϲϵϮ ͲŵĂŝů͗ĞƐΛƚĐƵ͘ŐŽ͘ƚnj͖tĞďƐŝƚĞ͗ǁǁǁ͘ƚĐƵ͘ŐŽ͘ƚnj ,ŽƚůŝŶĞEƵŵďĞƌƐ͗нϮϱϱϳϲϱϬϮϳϵϵϬ͕нϮϱϱϲϳϰϲϱϲϮϯϳ ĂŶĚнϮϱϱϲϴϯϵϮϭϵϮϴ WŚLJƐŝĐĂůĚĚƌĞƐƐ͗ϳDĂŐŽŐŽŶŝ^ƚƌĞĞƚ͕ĂƌĞƐ^ĂůĂĂŵ JULY 2018 JULY 2018 INTRODUCTION By virtue of Regulation 38 of the University (General) Regulations GN NO. 226 of 2013 the effective management of students admission records is the key responsibility of the Commission on one hand and HLIs on other hand. To maintain a record of applicants selected to join undergraduate degrees TCU has prepared this publication which contains statistics of all students who joined HLIs from 2012/13 to 2017/18 academic year. It should be noted that from 2010/2011 to 2016/17 Admission Cycles admission into Bachelors’ degrees was done through Central Admission System (CAS) except for 2017/18 where the University Information Management System (UIMS) was used to receive and process admission data also provide feedback to HLIs. Hence the data used to prepare this publication was obtained from the two databases. Prof. Charles D. Kihampa Executive Secretary ~ 1 ~ Table 1: Students Admitted into HLIs between 2012/13 and 2017/18 Admission Cycles Sn Institution 2012-2013 2013-2014 2014-2015 2015-2016 2016-2017 2017-2018 F M Tota F M Tota F M Tota F M Tota F M Tota F M Tota l l l l l l 1 AbdulRahman Al-Sumait University 434 255 689 393 275 -

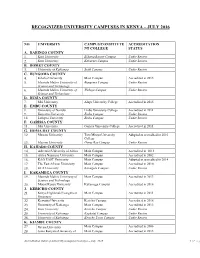

Recognized University Campuses in Kenya – July 2016

RECOGNIZED UNIVERSITY CAMPUSES IN KENYA – JULY 2016 NO. UNIVERSITY CAMPUS/CONSTITUTE ACCREDITATION NT COLLEGE STATUS A. BARINGO COUNTY 1. Kisii University Eldama Ravine Campus Under Review 2. Kisii University Kabarnet Campus Under Review B. BOMET COUNTY 3. University of Kabianga Sotik Campus Under Review C. BUNGOMA COUNTY 4. Kibabii University Main Campus Accredited in 2015 5. Masinde Muliro University of Bungoma Campus Under Review Science and Technology 6. Masinde Muliro University of Webuye Campus Under Review Science and Technology D. BUSIA COUNTY 7. Moi University Alupe University College Accredited in 2015 E. EMBU COUNTY 8. University of Nairobi Embu University College Accredited in 2011 9. Kenyatta University Embu Campus Under Review 10. Laikipia University Embu Campus Under Review F. GARISSA COUNTY 11. Moi University Garissa University College Accredited in 2011 G. HOMA BAY COUNTY 12. Maseno University Tom Mboya University Adopted as accredited in 2016 College 13. Maseno University Homa Bay Campus Under Review H. KAJIADO COUNTY 14. Adventist University of Africa Main Campus Accredited in 2013 15. Africa Nazarene University Main Campus Accredited in 2002 16. KAG EAST University Main Campus Adopted as accredited in 2014 17. The East African University Main Campus Accredited in 2010 18. KCA University Kitengela Campus Under Review I. KAKAMEGA COUNTY 19. Masinde Muliro University of Main Campus Accredited in 2013 Science and Technology 20. Mount Kenya University Kakamega Campus Accredited in 2016 J. KERICHO COUNTY 21. Kenya Highlands Evangelical Main Campus Accredited in 2011 University 22. Kenyatta University Kericho Campus Accredited in 2016 23. University of Kabianga Main Campus Accredited in 2013 24. -

The Case of Kashim Ibrahim Library, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln April 2006 The Challenges of Computerizing a University Library in Nigeria: The Case of Kashim Ibrahim Library, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria Grace Nok Ahmadu Bello University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Nok, Grace, "The Challenges of Computerizing a University Library in Nigeria: The Case of Kashim Ibrahim Library, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria" (2006). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 78. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/78 Library Philosophy and Practice Vol. 8, No. 2 (Spring 2006) (libr.unl.edu:2000/LPP/lppv8n2.htm) ISSN 1522-0222 The Challenges of Computerizing a University Library in Nigeria: the Case of Kashim Ibrahim Library, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria Grace Nok Senior Librarian Kashim Ibrahim Library Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria Introduction Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria is one of Nigeria's first generation universities, opening its doors in 1962. Like other universities, its functions include teaching, research, and community service. Ifidon and Okoli (2002) note that universities now have additional functions: • pursuit, promotion, and dissemination of knowledge; • provision of intellectual leadership; -

Digital Skills in Sub-Saharan Africa Spotlight on Ghana

Digital Skills in Sub-Saharan Africa Spotlight on Ghana IN COOPERATION WITH: ABOUT IFC Research and writing underpinning the report was conducted by the L.E.K. Global Education practice. The L.E.K. IFC—a sister organization of the World Bank and member of team was led by Ashwin Assomull, Maryanna Abdo, and the World Bank Group—is the largest global development Ridhi Gupta, including writing by Maryanna Abdo, Priyanka institution focused on the private sector in emerging Thapar, and Jaisal Kapoor and research contributions by Neil markets. We work with more than 2,000 businesses Aneja, Shrrinesh Balasubramanian, Patrick Desmond, Ridhi worldwide, using our capital, expertise, and influence to Gupta, Jaisal Kapoor, Rohan Sur, and Priyanka Thapar. create markets and opportunities in the toughest areas of Sudeep Laad provided valuable insights on the Ghana the world. For more information, visit www.ifc.org. market landscape and opportunity sizing. ABOUT REPORT L.E.K. is a global management consulting firm that uses deep industry expertise and rigorous analysis to help business This publication, Digital Skills in Sub-Saharan Africa: Spotlight leaders achieve practical results with real impact. The Global on Ghana, was produced by the Manufacturing Agribusiness Education practice is a specialist international team based in and Services department of the International Finance Singapore serving a global client base from China to Chile. Corporation, in cooperation with the Global Education practice at L.E.K. Consulting. It was developed under the ACKNOWLEDGMENTS overall guidance of Tomasz Telma (Senior Director, MAS), The report would not have been possible without the Mary-Jean Moyo (Director, MAS, Middle-East and Africa), participation of leadership and alumni from eight case study Elena Sterlin (Senior Manager, Global Health and Education, organizations, including: MAS) and Olaf Schmidt (Manager, Services, MAS, Sub- Andela: Lara Kok, Executive Coordinator; Anudip: Dipak Saharan Africa). -

Education Quarterly Reviews

Education Quarterly Reviews Siluyele, Nimrod, Nkonde, Edward, Mweemba, Malawo, Kaluba, Goodhope, and Zulu, Cleopas. (2020), A Survey on Student Preferences of Facilities and Models of Accommodation at Kapasa Makasa University, Zambia. In: Education Quarterly Reviews, Vol.3, No.2, 261-270. ISSN 2621-5799 DOI: 10.31014/aior.1993.03.02.138 The online version of this article can be found at: https://www.asianinstituteofresearch.org/ Published by: The Asian Institute of ResearcH The Education Quarterly Reviews is an Open Access publication. It may be read, copied, and distributed free of charge according to the conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. The Asian Institute of ResearcH Education Quarterly Reviews is a peer-reviewed International Journal. THe journal covers scholarly articles in the fields of education, linguistics, literature, educational theory, research, and metHodologies, curriculum, elementary and secondary education, HigHer education, foreign language education, teacHing and learning, teacHer education, education of special groups, and other fields of study related to education. As tHe journal is Open Access, it ensures HigH visibility and tHe increase of citations for all researcH articles published. The Education Quarterly Reviews aims to facilitate scholarly work on recent theoretical and practical aspects of education. The Asian Institute of ResearcH Education Quarterly Reviews Vol.3, No.2, 2020: 261-270 ISSN 2621-5799 CopyrigHt © The AutHor(s). All RigHts Reserved DOI: 10.31014/aior.1993.03.02.138 -

LIS Guidelines

Africa Accreditors Ways of Ways of Ways to review performance LIS Schools looking at looking at performance outcomes 1 Botswana No reply University of Botswana 2 Egypt No reply Cairo University, Department of libraries and archival studies 3 Marocco No accreditation [email protected] 4 Kenia No reply Kenya School of Professional Studies Moi University 5 Namibia No reply University of Namibia 6 Nigeria No reply Bayero University, Kano University of Ibadan 7 Rwanda No reply - National University of Rwanda, Department of Computer Sciences 8 South Africa Government Resources, Student The quality assurance guidelines are based University of Zululand Agency (South evaluation of on SAQA Department of Education [email protected] African Data on the learning policies and followed by University Qualification students, experience approved quality assurance guidelines. The University of Western Cape Authority(SAQA) QA procedure is taken annually by Design and Assessment of external assessor and occasionally by University content of the student SAQA . program learning It is the University policy that departments External Assessors outcomes invite external assessor at least once in through exams every three years. Guidelines for external and/or assessors is provided with the policy and employers include items highlighted in this evaluations questionnaire. The government(Department of Education does solicit information on programmes offered at the University occasionally( eg within three years). Such information is used to determine the viability and suitability of qualifications. There are no policies or guidelines targeting LIS sector only. Site visit takes place and a self-evaluation report is delivered to the evaluation body. No public report is done as follow up. -

00100, Nairobi, Kenya Phone 0722980511/0733515310 Email Address: [email protected] [email protected]

Lecturer-Department of Sociology Kenyatta University P.O. Box 43844- 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Phone 0722980511/0733515310 Email address: [email protected] [email protected] Qualifications PhD, Sociology, Kenyatta University, Kenya MA, Sociology, University of Nairobi Postgraduate Diploma in Education, University of Nairobi BA, Kenyatta University, Kenya Fellowship Fellow of the African Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship (ADDRF) PUBLICATIONS Muiya, B. M. (2010). The effects of cost-sharing on healthcare services provision in Kenya: Utilization, Management and Access. Lambard Educational Publishers. Muiya, B. M. (2014 –awaiting publication). Equity in healthcare provision: ensuring social protection in health through health insurance in Kenya. The Politics of Social Protection in Kenya Fifty Years after Political Independence. Nairobi: French Institute for Research in Africa (IFRA- Nairobi). Muiya, B. M. (2014, June). The nature, challenges and consequences of urban youth unemployment: A case of Nairobi City, Kenya. Horizon Research Publishing. Muiya, B. M., & Kamau, A. (2013, November). Universal health care in Kenya: Opportunities and challenges for the informal sector workers. International Journal of Education and Research, 1(11). 2 1 UNIVERSITY LEVEL TEACHING MATERIAL Maina, L. & Muiya, B. M. (2015) Crime Analysis & Prevention. Online Learning Material for the Digital School of Virtual and Open Learning, Kenyatta University Muiya, B. M. (2015) Introduction to Criminology. Online Learning Material for the Digital School of Virtual and Open Learning, Kenyatta University Muiya, B. M. (2015) Fundamentals of sociology. Online Learning Material for the Digital School of Virtual and Open Learning, Kenyatta University Muiya, B. M. (ed) (2015) Research methods & statistics. Online Learning Material for the Digital School of Virtual and Open Learning, Kenyatta University Muiya, B. -

The 9Th Toyin Falola Annual International Conference on Africa and the African Diaspora (Tofac 2019)

The 9th Toyin Falola Annual International Conference On Africa And The African Diaspora (tofac 2019) THEME: RELIGION, THE STATE AND GLOBAL POLITICS JULY 1-3, 2019 @BABCOCK UNIVERSITY ILISHAN-REMO, OGUN STATE, NIGERIA PROGRAMME OF EVENTS FEATURING: DISTINGUISHED GUEST OF HONOUR CHIEF DR OLUSEGUN OBASANJO, GCFR, PhD Former President, Federal Republic of Nigeria CHIEF HOST PROFESSOR ADEMOLA S. TAYO HOST President/Vice-Chancellor, Babcock PROFESSOR ADEMOLA DASYLVA University Board Chair, TOFAC (International) GRAND HOST HE CHIEF DR DAPO ABIODUN, MFR Executive Governor, Ogun State, Nigeria CONFERENCE KEYNOTE SPEAKERS HE Bishop Matthew Hassan Kukah, Bishop of the Catholic Diocese of Sokoto, Nigeria Professor Bankole Omotoso, Writer, Dean, Faculty of Humanities, Elizade University Professor Ibigbolade Aderibigbe, Professor of Religion & Associate Director, The African Studies Institute, University of Georgia, Athens, USA BANQUET CHAIRMAN: His Imperial Majesty Fuankem Achankeng I, MA, MA, PhD The Nyatema of Atoabechied Ruler, Atoabechied, Lebialem Southwestern Cameroon & Professor, University of Wisconsin, Oshkosh, USA BANQUET SPECIAL GUEST OF HONOUR Professor Jide Owoeye Chairman, Governing Council & Proprietor Lead City University, Ibadan 2 NATIONAL ANTHEM Great lofty heights attain To build a nation where peace Arise, O compatriot, And justice shall reign. Nigeria’s call obey To serve our father’s land BABCOCK UNIVERSITY With love and strength and faith The labour of our heroes past ANTHEM Shall never be in vain Hail Babcock God’s own University To serve with heart and mind Built on the power of His Word One nation bound in freedom Knowledge and truth, Peace and unity Service to God and man Building a future for the youth Wholistic education, O God of creation, The vision is still aflame: Direct our noble cause Mental, physical, social, spiritual Guide our leaders right Babcock is it! Help our youths the truth to know Hail, Babcock God’s own University In love and honesty to grow Good life here and forever more.