December 2020 Meeting Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Militarisation of Space 14 June 2021

By, Claire Mills The militarisation of space 14 June 2021 Summary 1 Space as a new military frontier 2 Where are military assets in space? 3 What are counterspace capabilities? 4 The regulation of space 5 Who is leading the way on counterspace capabilities? 6 The UK’s focus on space commonslibrary.parliament.uk Number 9261 The militarisation of space Contributing Authors Patrick Butchard, International Law, International Affairs and Defence Section Image Credits Earth from Space / image cropped. Photo by ActionVance on Unsplash – no copyright required. Disclaimer The Commons Library does not intend the information in our research publications and briefings to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. We have published it to support the work of MPs. You should not rely upon it as legal or professional advice, or as a substitute for it. We do not accept any liability whatsoever for any errors, omissions or misstatements contained herein. You should consult a suitably qualified professional if you require specific advice or information. Read our briefing ‘Legal help: where to go and how to pay’ for further information about sources of legal advice and help. This information is provided subject to the conditions of the Open Parliament Licence. Feedback Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained in these publicly available briefings is correct at the time of publication. Readers should be aware however that briefings are not necessarily updated to reflect subsequent changes. If you have any comments on our briefings please email [email protected]. Please note that authors are not always able to engage in discussions with members of the public who express opinions about the content of our research, although we will carefully consider and correct any factual errors. -

Foi-R--5077--Se

Omvärldsanalys Rymd 2020 Fokus på försvar och säkerhet Sandra Lindström (red.), Kristofer Hallgren, Seméli Papadogiannakis, Ola Rasmusson, John Rydqvist och Jonatan Westman FOI-R--5077--SE Januari 2021 Sandra Lindström (red.), Kristofer Hallgren, Seméli Papadogiannakis, Ola Rasmusson, John Rydqvist och Jonatan Westman Omvärldsanalys Rymd 2020 Fokus på försvar och säkerhet FOI-R--5077--SE Titel Omvärldsanalys Rymd 2020 – Fokus på försvar och säkerhet Title Global Space Trends 2020 for Defence and Security Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--5077--SE Månad/Month Januari Utgivningsår/Year 2021 Antal sidor/Pages 127 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Försvarsmakten Forskningsområde Flygsystem och rymdfrågor FoT-område Sensorer och signaturanpassningsteknik Projektnr/Project no E60966 Godkänd av/Approved by Lars Höstbeck Ansvarig avdelning Försvars- och säkerhetssystem Bild/Cover: Tre gröna lasrar från Starfire Optical Range på Kirtland Air Force Base i New Mexico, USA. Anläggningen används bland annat för inmätning av objekt i låga satellitbanor. Den allmänna uppfattningen (men ej officiell) är att lasern även kan användas som ASAT-vapen. Källa: Directed Energy Directorate, US Air Force. Detta verk är skyddat enligt lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk, vilket bl.a. innebär att citering är tillåten i enlighet med vad som anges i 22 § i nämnd lag. För att använda verket på ett sätt som inte medges direkt av svensk lag krävs särskild överenskommelse. This work is protected by the Swedish Act on Copyright in Literary and Artistic Works (1960:729). Citation is permitted in accordance with article 22 in said act. Any form of use that goes beyond what is permitted by Swedish copyright law, requires the written permission of FOI. -

Aas 21-290 Cislunar Space Situational Awareness

AAS 21-290 CISLUNAR SPACE SITUATIONAL AWARENESS Carolin Frueh*, Kathleen Howell†, Kyle J. DeMars‡, Surabhi Bhadauria§ Classically, space situational awareness (SSA) and space traffic management (STM) focus on the near-Earth region, which is highly populated by satellites and space debris objects. With the expansion of space activities further in the cislunar space, the problems of SSA and STM arise anew in regions far away from the near-Earth realm. This paper investigates the conditions for successful Space Situational Awareness and Space Traffic Management in the cislunar region by drawing a direct comparison to the known challenges and solutions in the near-Earth realm, highlighting similarities and differences and their implications on Space Traffic Management engineering solutions. INTRODUCTION Space Situational Awareness (SSA), sometimes called Space Domain Awareness (SDA), can be understood as summary terms for the comprehensive knowledge on all objects in a specific region without necessarily having direct communication to those objects. Space Traffic Management (STM), as an extrapolatory term, is applying the SSA knowledge to manage this said region to enable sustainable use. All three of those terms have traditionally been applied to the realm of the near-Earth space, usually expanding from low Earth orbit (LEO) to hyper geostationary orbit (hyper-GEO), and the objects of interest are objects in orbital motion for which the dominant astrodynamical term is the central gravitational potential of the Earth. Space Traffic Management (STM) aims at engineering solutions, methods, and protocols that allow regulating space fairing in a manner enabling the sustainable use of space. SSA and SDA thereby provide the knowledge-base for STM, and the areas are heavily intertwined. -

Tailoring Deterrence for China in Space for More Information on This Publication, Visit

C O R P O R A T I O N KRISTA LANGELAND, DEREK GROSSMAN Tailoring Deterrence for China in Space For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA943-1. About RAND The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. To learn more about RAND, visit www.rand.org. Research Integrity Our mission to help improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis is enabled through our core values of quality and objectivity and our unwavering commitment to the highest level of integrity and ethical behavior. To help ensure our research and analysis are rigorous, objective, and nonpartisan, we subject our research publications to a robust and exacting quality-assurance process; avoid both the appearance and reality of financial and other conflicts of interest through staff training, project screening, and a policy of mandatory disclosure; and pursue transparency in our research engagements through our commitment to the open publication of our research findings and recommendations, disclosure of the source of funding of published research, and policies to ensure intellectual independence. For more information, visit www.rand.org/about/principles. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © 2021 RAND Corporation is a registered trademark. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0703-0 Cover: Long March 5 Y2 by 篁竹水声 Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. -

Securing Japan an Assessment of Japan´S Strategy for Space

Full Report Securing Japan An assessment of Japan´s strategy for space Report: Title: “ESPI Report 74 - Securing Japan - Full Report” Published: July 2020 ISSN: 2218-0931 (print) • 2076-6688 (online) Editor and publisher: European Space Policy Institute (ESPI) Schwarzenbergplatz 6 • 1030 Vienna • Austria Phone: +43 1 718 11 18 -0 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.espi.or.at Rights reserved - No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or for any purpose without permission from ESPI. Citations and extracts to be published by other means are subject to mentioning “ESPI Report 74 - Securing Japan - Full Report, July 2020. All rights reserved” and sample transmission to ESPI before publishing. ESPI is not responsible for any losses, injury or damage caused to any person or property (including under contract, by negligence, product liability or otherwise) whether they may be direct or indirect, special, incidental or consequential, resulting from the information contained in this publication. Design: copylot.at Cover page picture credit: European Space Agency (ESA) TABLE OF CONTENT 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background and rationales ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Objectives of the Study ................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Methodology -

Next Generation Space Defense May 2021

Next Generation Space Defense MilsatMagazineMilsatMagazine May 2021 Cover image: United Launch Alliance’s Delta IV Heavy rocket carrying the NROL-82 mission for the National Reconnaissance Office lifts off from Space Launch Complex-6 at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Image Source: United Launch Alliance Beyond Secure Satcoms Publishing OPeratiOns disPatChes Features Eutelsat + OneWeb .................................................. 4 How SATCOM Vastly Improves .............................. 12 Silvano Payne, Publisher + Executive Writer Small UAV Flexibility Simon Payne, Chief Technical Officer Author: Get SAT Hartley G. Lesser, Editorial Director ULA + NRO ............................................................... 6 Pattie Lesser, Executive Editor Donald McGee, Production Manager USSF/SMC + Raytheon I&S ...................................... 8 Teresa Sanderson, Operations Director Sean Payne, Business Development Manager Lockheed Martin ....................................................... 8 Dan Makinster, Technical Advisor High Availability Maritime SATCOM....................... 18 Starts On The Ship Space Flight Laboratory ......................................... 10 Author: Dr. Rowan Gilmore, EM Solutions seniOr COlumnists Virgin Orbit ............................................................ 11 and COntributOrs Hughes + OneWeb ................................................. 15 Delivering Mission-Critical Connectivity with ........ 28 Chris Forrester, Broadgate Publications Reliability and Resilience Loft Orbital -

APSCC Monthly E-Newsletter

APSCC Monthly e‐Newsletter August 2020 The Asia‐Pacific Satellite Communications Council (APSCC) e‐Newsletter is produced on a monthly basis as part of APSCC’s information services for members and professionals in the satellite industry. Subscribe to the APSCC monthly newsletter and be updated with the latest satellite industry news as well as APSCC activities! To renew your subscription, please visit www.apscc.or.kr. To unsubscribe, send an email to [email protected] with a title “Unsubscribe.” News in this issue has been collected from July 1 to July 31. INSIDE APSCC APSCC 2020 Conference Series Starts from August 18: LIVE Every Tuesday 9AM HK l Singapore Time from August 18 to November 17 APSCC 2020 is the largest annual event of the Asia Pacific satellite community, which incorporates industry veterans, local players as well as new players into a single platform in order to reach out to a wide-ranging audience. Organized by the Asia Pacific Satellite Communications Council (APSCC), APSCC 2020 this year is even stretching further by going virtual and live. Every Tuesday mornings at 9 AM Hong Kong and Singapore time, new installments in APSCC 2020 will be presented live - in keynote speeches, panel discussions, and in presentations followed by Q&A format. Topics will range across a selection of issues the industry is currently grappling with globally, as well as in the Asia-Pacific region. Register now and get access to the complete APSCC 2020 Series with a single password. To register go to https://apsccsat.com. APSCC Summit@ConnecTechAsia (SatelliteAsia) September 29 ~ October 1, Online Event, https://www.connectechasia.com/satellite-asia/ The Asia-Pacific Satellite Communications Council (APSCC), in conjunction with Informa Markets, will present interactive online sessions at ConnecTechAsia 2020, Asia’s biggest telecom industry event. -

Commercial Crew Breakthrough PAGE 61

JAHNIVERSE 96 AEROPUZZLER 6 LOOKING BACK 94 Newton vs. Einstein Why not let him fl y? First jet operations from a carrier YEAR-IN-REVIEW Researchers, industry persevere through the pandemic. Commercial Crew breakthrough PAGE 61 DECEMBER 2020 | A publication of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics | aerospaceamerica.aiaa.org SPACE AND MISSILES will have NASA teams embedded in their projects Commercial Crew successes lead the as part of the 10-month base period disclosed in the Next Space Technologies for Exploration Part- way in a pivotal year nerships Appendix H Broad Agency Announce- BY JESUS A. OROZCO AND CHRISTOPHER R. SIMPSON ment. In May, NASA and SpaceX launched U.S. as- The Space Operations and Support Technical Committee focuses on tronauts in a Crew Dragon capsule on a Falcon 9 operations and relevant technology developments for crewed and uncrewed missions in Earth orbital and planetary operations. rocket from Kennedy Space Center in Florida. As- tronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken arrived at NASA launch ushered in the era of com- the International Space Station 19 hours later on mercial spacefl ight, the U.S. Space Force the Demo-2 mission. The Crew Dragon remained launched its fi rst payload and three gov- docked to the ISS for 63 days before bringing the A ernments launched Mars missions while astronauts back to Earth; the capsule splashed the covid-19 pandemic paralyzed the world for down in the Gulf of Mexico. Neil Mallik, network most of the year. director of the Human Space Flight Communi- The Space Force completed the military’s cation and Tracking Network at NASA’s Goddard next-generation communications constellation Space Flight Center in Maryland, said that NASA with its March launch of the Advanced Extremely evolved to support “commercial human space- High Frequency-6 satellite. -

NASA) Transition Briefing Document Prepared by NASA for the Incoming Biden Administration 2020

Description of document: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) transition briefing document prepared by NASA for the incoming Biden Administration 2020 Requested date: 01-January-2021 Release date: 04-January-2021 Posted date: 22-February-2021 Source of document: FOIA Request NASA Headquarters 300 E Street, SW Room 5Q16 Washington, DC 20546 Fax: (202) 358-4332 Email: [email protected] Online FOIA submission form The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Headquarters Washington, DC 20546-0001 January 4, 2021 Reply to attn.of Office of Communications Re: FOIA Tracking Number 21-HQ-F-00169 This responds to your Freedom oflnformation Act (FOIA) request to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), dated January 1, 2021, and received in this office on January 4, 2021. -

China's Space Programme

LAU CHINA INSTITUTE POLICY SERIES 2020 China in the World | 02 China’s space programme A rising star, a rising challenge Dr Mark Hilborne LAU CHINA INSTITUTE POLICY SERIES 2020 | CHINA IN THE WORLD | 02 In Partnership with School of Security Studies 2 LAU CHINA INSTITUTE POLICY SERIES 2020 | CHINA IN THE WORLD | 02 Foreword These days, we talk often of Global China – So too is the ambiguity around what China a place which is the main trading partner for is doing. Yes, it conveys its operations as over 120 countries, and which has interests ones that advance human knowledge and that stretch across the earth, reaching into understanding. But the technology is it even the most remote areas like the South developing and using, though presented and North Pole. But what is often forgotten as purely civilian, of course have military is that China has strong, and very realistic, application. And while China in space might aspirations into outer space. That is the focus seem remote from more earthly concerns, of this clear and timely paper, the second in it does give China access not only to the Lau China Institute Policy Paper Series. symbolic power, but, beyond that, a real area in which to have satellites and other China in outer space is not so dissimilar to hard capacity that are all too easy to shift the China we see in the unclaimed territory from benign to more unsettling uses. of the Antarctica. Here, the country is presented with a huge new opportunity, one China in outer space is an urgent and bound by very broad treaties which have important topic. -

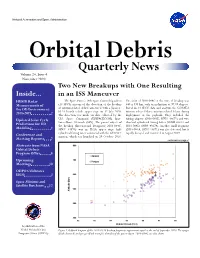

Quarterly News Volume 24, Issue 4 November 2020 Two New Breakups with One Resulting Inside

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Orbital Debris Quarterly News Volume 24, Issue 4 November 2020 Two New Breakups with One Resulting Inside... in an ISS Maneuver HUSIR Radar The Space Force’s 18th Space Control Squadron The orbit of 2018-084C at the time of breakup was Measurements of (18 SPCS) announced the detection of the breakup 643 x 595 km, with an inclination of 97.89 degrees. the OD Environment: of mission-related debris associated with a Japanese Based on 18 SPCS’ data and analysis, the GOSAT-2 H-2A launch vehicle upper stage on 12 July 2020. mission released three mission-related debris during 2018-2019 2 The detection was made via data collected by the deployment of the payloads. They included the Updated Solar Cycle U.S. Space Command (USSPACECOM) Space fairing adapter (2018-084E, SSN# 43675) and two Surveillance Network (SSN). The parent object of identical cylindrical fairing halves (SSN# 43673 and Predictions for OD the breakup (International Designator 2018-084C, 2018-084D, SSN# 43674). Another small fragment Modeling 4 SSN# 43673) was an H-2A upper stage half- (2018-084A, SSN# 43671) was also detected, but it cylindrical fairing cover associated with the GOSAT-2 rapidly decayed and reentered in August 2019. Conference and mission, which was launched on 29 October 2018. Meeting Reports 7 continued on page 2 Abstracts from NASA ϴϬϬ Orbital Debris Program Office 8 ƉŽŐĞĞ ϳϬϬ Upcoming WĞƌŝŐĞĞ Meetings 10 ODPO Celebrates ISS20 2 ϲϬϬ ;ŬŵͿ Space Missions and Satellite Box Score 12 ϱϬϬ ůƚŝƚƵĚĞ ϰϬϬ ϯϬϬ ϵϮ ϵϯ ϵϰ ϵϱ ϵϲ ϵϳ ϵϴ KƌďŝƚĂůWĞƌŝŽĚ;ŵŝŶͿ A publication of the NASA Orbital Debris Figure 1. -

The Future of Security in Space: a Thirty-Year US Strategy

APRIL 2021 The Future of Security in Space: A Thirty-Year US Strategy Lead Authors: Clementine G. Starling, Mark J. Massa, Lt Col Christopher P. Mulder, and Julia T. Siegel With a Foreword by Co-Chairs General James E. Cartwright, USMC (ret.) and Secretary Deborah Lee James In Collaboration with: Raphael Piliero Christopher J. MacArthur Brett M. Williamson Alexander Powell Hays Dor W. Brown IV Christian Trotti Ross Lott Olivia Popp The Future of Security in Space: A Thirty-Year US Strategy Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world. The Center honors General Brent Scowcroft’s legacy of service and embodies his ethos of nonpartisan commitment to the cause of security, support for US leadership in cooperation with allies and partners, and dedication to the mentorship of the next generation of leaders. Forward Defense Forward Defense helps the United States and its allies and partners contend with great-power competitors and maintain favorable balances of power. This new practice area in the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security produces Forward-looking analyses of the trends, technologies, and concepts that will define the future of warfare, and the alliances needed for the 21st century. Through the futures we forecast, the scenarios we wargame, and the analyses we produce, Forward Defense develops actionable strategies and policies for deterrence and defense, while shaping US and allied operational concepts and the role of defense industry in addressing the most significant military challenges at the heart of great-power competition.