Toccata Classics TOCC 0128 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAN 9722 Front.Qxd 25/7/07 3:07 Pm Page 1

CHAN 9722 Front.qxd 25/7/07 3:07 pm Page 1 CHAN 9722 CHANDOS Schnittke (K)ein Sommernachtstraum Cello Concerto No. 2 Alexander Ivashkin cello Russian State Symphony Orchestra Valeri Polyansky CHAN 9722 BOOK.qxd 25/7/07 3:08 pm Page 2 Alfred Schnittke (1934–1998) Cello Concerto No. 2* 42:00 1 I Moderato – 3:20 2 II Allegro 9:34 3 III Lento – 8:26 4 IV Allegretto mino – 4:34 5 V Grave 16:05 6 10:37 Nigel LuckhurstNigel (K)ein Sommernachtstraum (Not) A Midsummer Night’s Dream TT 52:50 Alexander Ivashkin cello* Russian State Symphony Orchestra Valeri Polyansky Alfred Schnittke 3 CHAN 9722 BOOK.qxd 25/7/07 3:08 pm Page 4 us to a point where nothing is single-faced ‘Greeting Rondo’ with elements from the First Alfred Schnittke: Cello Concerto No. 2/(K)ein Sommernachtstraum and everything is doubtful and double-folded. Symphony creeping into it; one can hear all The fourth movement is a new and last the sharp polystylistic shocking contrasts outburst of activity, of confrontation between similar to Schnittke’s First Symphony in The Second Cello Concerto (1990) is one of different phases and changes as if through a hero (the soloist) and a mob (the orchestra). condensed form here. (K)ein Sommernachts- Schnittke’s largest compositions. The musical different ages. The first subject is excessively Again, two typical elements are juxtaposed traum, written just before the composer’s fatal palate of the Concerto is far from simple, and active and turbulent, the second more here with almost cinematographical clarity: illness began to hound him, is one of his last the cello part is fiendishly difficult. -

NIKOLAI KORNDORF: a BRIEF INTRODUCTION by Martin Anderson Nikolai Korndorf Had a Clear Image of What Kind of a Composer He Was

Explore Unknown Music with the Toccata Discovery Club Since you’re reading this booklet, you’re obviously someone who likes to explore music more widely than the mainstream offerings of most other labels allow. Toccata Classics was set up explicitly to release recordings of music – from the Renaissance to the present day – that the microphones have been ignoring. How often have you heard a piece of music you didn’t know and wondered why it hadn’t been recorded before? Well, Toccata Classics aims to bring this kind of neglected treasure to the public waiting for the chance to hear it – from the major musical centres and from less-well-known cultures in northern and eastern Europe, from all the Americas, and from further afield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, Toccata Classics will be exploring it. To link label and listener directly we have launched the Toccata Discovery Club, which brings its members substantial discounts on all Toccata Classics recordings, whether CDs or downloads, and also on the range of pioneering books on music published by its sister company, Toccata Press. A modest annual membership fee brings you two free CDs when you join (so you are saving from the start) and opens up the entire Toccata Classics catalogue to you, both new recordings and existing releases. Frequent special offers bring further discounts. If you are interested in joining, please visit the Toccata Classics website at www.toccataclassics.com and click on the ‘Discovery Club’ tab for more details. 8 TOCC 0128 Korndorf.indd 1 26/03/2012 17:30 NIKOLAI KORNDORF: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION by Martin Anderson Nikolai Korndorf had a clear image of what kind of a composer he was. -

![Pdf May 2010, "Dvoinaia Pererabotka Otkhodov V Sovetskoi [3] ‘New Beginnings](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7586/pdf-may-2010-dvoinaia-pererabotka-otkhodov-v-sovetskoi-3-new-beginnings-787586.webp)

Pdf May 2010, "Dvoinaia Pererabotka Otkhodov V Sovetskoi [3] ‘New Beginnings

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 368 3rd International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2019) Multifaceted Creativity: Legacy of Alexander Ivashkin Based on Archival Materials and Publications Elena Artamonova Doctor of Philosophy University of Central Lancashire Preston, United Kingdom E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—Professor Alexander Vasilievich Ivashkin (1948- numerous successful international academic and research 2014) was one of the internationally eminent musicians and projects, symposia and competitions, concerts and festivals. researchers at the turn of the most recent century. His From 1999 until his death in 2014, as the Head of the Centre dedication, willpower and wisdom in pioneering the music of for Russian Music at Goldsmiths, he generated and promoted his contemporaries as a performer and academic were the interdisciplinary events based on research and archival driving force behind his numerous successful international collections. The Centre was bursting with concert and accomplishments. This paper focuses on Ivashkin’s profound research life, vivacity and activities of high calibre attracting knowledge of twentieth-century music and contemporary international attention and interest among students and analysis in a crossover of cultural-philosophical contexts, scholars, professionals and music lovers, thus bringing together with his rare ability to combine everything in cultural dialogue across generations and boarders to the retrospect and make his own conclusions. His understanding of inner meaning and symbolism bring new conceptions to wider world. His prolific collaborations, including with the Russian music, when the irrational becomes a new stimulus for London Philharmonic Orchestra, the Southbank Centre, the rational ideas. The discussion of these subjects relies heavily on BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Barbican Centre and unpublished archival and little-explored publications of Wigmore Hall, St. -

Concerto Capriccioso Recorded Live at the Great Hall Of

Concerto capriccioso recorded live at the Great Hall of Moscow Conservatoire, 21 November 2005 Recording engineer: Farida Uzbekova Triptych recorded live at the Lazaridis Theatre, Perimeter Institute, Waterloo, Canada, 1 December 2006 (courtesy of Marshall Arts Productions) Recording engineer: Ed Marshall, Marshall Arts Productions Passacaglia recorded at Studio One, Moscow Radio House, 3–6 August 2001 (courtesy of Megadisc Records) Recording engineer: Liubov Doronina Recordings remastered by Richard Black, Recording Rescue, London Booklet essays: Martin Anderson and Alexander Ivashkin Design and layout: Paul Brooks, Design and Print, Oxford Executive Producer: Martin Anderson TOCC 0128 © 2012, Toccata Classics, London P 2012, Toccata Classics, London Toccata Classics CDs can be ordered from our distributors around the world, a list of whom can be found at www.toccataclassics.com. If we have no representation in your country, please contact: Toccata Classics, 16 Dalkeith Court, Vincent Street, London SW1P 4HH, UK Tel: +44/0 207 821 5020 Fax: +44/0 207 834 5020 E-mail: [email protected] TOCC 0128 Korndorf.indd 1 05/04/2012 14:07 Anya Alexeyev has performed extensively in many countries across Europe as well as in the USA, Canada, Argentina, Malaysia and South Africa. She has performed many times in all of London’s NIKOLAI KORNDORF: A BRIEF INTRODUCTION major concert halls, as well as in such venues as the Philharmonie in Berlin, the Konzerthaus in by Martin Anderson Vienna, Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, Herodes Atticus Theatre in Athens, Bridgewater Hall in Manchester, the Great Hall of the Moscow Conservatoire, Philharmonia Hall in St Petersburg, Nikolai Korndorf had a clear image of what kind of a composer he was. -

Alfred Schnittke Concerto Grosso No.1 Symphony No.9

alfred schnittke Concerto grosso No.1 SHARON BEZALY FLUTE CHRISTOPHER COWIE OBOE Symphony No.9 CAPE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA OWAIN ARWEL HUGHES CAPE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA KAAPSE FILHARMONIESE ORKES I-okhestra yomculo yaseKoloni BIS-CD-1727 BIS-CD-1727_f-b.indd 1 09-05-18 16.16.53 BIS-CD-1727 Alf:booklet 11/5/09 12:58 Page 2 SCHNITTKE, Alfred (1934–98) Concerto grosso No. 1 (1977) (Sikorski) 27'13 Version for flute, oboe, harpsichord, prepared piano and string orchestra (1988) world première recording 1 I. Preludio. Andante 4'46 2 II. Toccata. Allegro 4'33 3 III. Recitativo. Lento 6'39 4 IV. Cadenza 2'11 5 V. Rondo. Agitato 6'45 6 VI. Postludio. Andante 2'13 Sharon Bezaly flute · Christopher Cowie oboe Grant Brasler harpsichord · Albert Combrink piano Symphony No. 9 (1997) (Sikorski) 33'19 Reconstruction by Alexander Raskatov (2006) 7 I. [Andante] 18'03 8 II. Moderato 7'57 9 III. Presto 7'01 TT: 61'24 Cape Philharmonic Orchestra Farida Bacharova leader Owain Arwel Hughes conductor 2 BIS-CD-1727 Alf:booklet 11/5/09 12:58 Page 3 lfred Schnittke (1934–98) needs very little introduction. His music has been performed countless times all around the world and recorded on A numerous compact discs released by different companies. His major com positions – nine symphonies, three operas, ballets, concertos, concerti grossi, sonatas for various instruments – have been heard on every continent. In Schnitt - ke’s music we find a mixture of old and new styles, of modern, post-modern, clas sical and baroque ideas. It reflects a very complex, peculiar and fragile men - tality of the late twentieth century. -

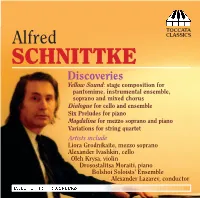

Toccata Classics TOCC 0091 Notes

TOCCATA Alfred CLASSICS SCHNITTKE Discoveries Yellow Sound: stage composition for pantomime, instrumental ensemble, soprano and mixed chorus Dialogue for cello and ensemble Six Preludes for piano Magdalina for mezzo soprano and piano Variations for string quartet Artists include Liora Grodnikaite, mezzo soprano Alexander Ivashkin, cello Oleh Krysa, violin Drosostalitsa Moraiti, piano Bolshoi Soloists’ Ensemble Alexander Lazarev, conductor SCHNITTKE DISCOVERIES by Alexander Ivashkin This CD presents a series of ive works from across Alfred Schnittke’s career – all of them unknown to the wider listening public but nonetheless giving a conspectus of the evolution of his style. Some of the recordings from which this programme has been built were unreleased, others made specially for this CD. Most of the works were performed and recorded from photocopies of the manuscripts held in Schnittke’s family archive in Moscow and in Hamburg and at the Alfred Schnittke Archive in Goldsmiths, University of London. Piano Preludes (1953–54) The Piano Preludes were written during Schnittke’s years at the Moscow Conservatory, 1953–54; before then he had studied piano at the Moscow Music College from 1949 to 1953. An advanced player, he most enjoyed Rachmaninov and Scriabin, although he also learned and played some of Chopin’s Etudes as well as Rachmaninov’s Second and the Grieg Piano Concerto. It was at that time that LPs irst became available in the Soviet Union, and so he was able to listen to recordings of Wagner’s operas and Scriabin’s orchestral music. The piano style in the Preludes is sometimes very orchestral, relecting his interest in the music of these composers. -

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director

Toronto Symphony Orchestra Sir Andrew Davis, Interim Artistic Director Saturday, February 23, 2019 at 8:00pm National Arts Centre Orchestra Alexander Shelley, Music Director John Storgårds, Principal Guest Conductor Pinchas Zukerman, Conductor Emeritus Jack Everly, Principal Pops Conductor Alain Trudel, Principal Youth and Family Conductor Alexander Shelley, conductor Yosuke Kawasaki, violin Jessica Linnebach, violin David Fray, piano Jocelyn Morlock Cobalt Frédéric Chopin Piano Concerto No. 2 in F Minor, Op. 21 I. Maestoso II. Larghetto III. Allegro vivace Intermission Robert Schumann Symphony No. 1 in B-flat Major, Op. 38 “Spring” I. Andante un poco maestoso – Allegro molto vivace II. Larghetto III. Scherzo: Molto vivace IV. Allegro animato e grazioso This concert is dedicated to The Honourable Hilary M. Weston and Mr. W. Galen Weston. As a courtesy to musicians, guest artists, and fellow concertgoers, please put your phone away and on silent during the performance. FEBRUARY 23, 2019 39 ABOUT THE WORKS Jocelyn Morlock Cobalt 7 Born: St. Boniface, Manitoba, December 14, 1969 min Composed: 2009 Jocelyn Morlock received her Bachelor of city’s innovative concert series Music on Main Music degree in piano performance at Brandon (2012–2014). University, and both a master’s degree and a Most of Morlock’s compositions are for Doctorate of Musical Arts from the University small ensembles, many of them for unusual of British Columbia. Among her teachers were combinations like piano and percussion Pat Carrabré, Stephen Chatman, Keith Hamel, (Quoi?), cello and vibraphone (Shade), bassoon and the late Russian-Canadian composer and harp (Nightsong), and an ensemble Nikolai Korndorf. consisting of clarinet/bass clarinet, trumpet, “With its shimmering sheets of harmonics” violin, and double bass (Velcro Lizards). -

FROM the HEAD of DEPARTMENT the Major Piece of Research

FROM THE HEAD OF DEPARTMENT The major piece of research news over the past term an event that also saw a display of materials from the has undoubtedly been the release in December of Daphne Oram archive. Coincidentally, at about the the results of the Research Assessment Exercise. same time, we also secured the purchase of Daphne Keith Negus has given a full appraisal of these in Oram’s original ‘Oramics’ machine, one of the first his contribution below so I will simply reiterate his ever electronic music composition systems. We point that having 70% of the Department’s work rated anticipate that this will lead to some very interesting as being either ‘world leading’ or ‘internationally future strands of research, as well as potential excellent’ was an exceptionally good outcome for us, collaborations with other high-profile partners. and a result that, in percentage terms, was exceeded Another indicator of the Department’s high standing by only one other department within the College as a in music research is the number and quality of PhD whole. The RAE will soon give way to the Research students we are able to attract. Even so, it was Excellence Framework (REF), and we shall shortly something of a pleasant surprise when I discovered begin to contemplate the potential implications for that we have enrolled no fewer than 20 PhD students the Department of this revised method of research in the department in the last calendar year, two of assessment. But for the moment we can draw whom have joined us on AHRC-funded scholarships breath and congratulate ourselves on the very fine (making a total of five students in the Department achievement this time around. -

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS a Discography Of

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers H-P GAGIK HOVUNTS (see OVUNTS) AIRAT ICHMOURATOV (b. 1973) Born in Kazan, Tatarstan, Russia. He studied clarinet at the Kazan Music School, Kazan Music College and the Kazan Conservatory. He was appointed as associate clarinetist of the Tatarstan's Opera and Ballet Theatre, and of the Kazan State Symphony Orchestra. He toured extensively in Europe, then went to Canada where he settled permanently in 1998. He completed his musical education at the University of Montreal where he studied with Andre Moisan. He works as a conductor and Klezmer clarinetist and has composed a sizeable body of music. He has written a number of concertante works including Concerto for Viola and Orchestra No1, Op.7 (2004), Concerto for Viola and String Orchestra with Harpsicord No. 2, Op.41 “in Baroque style” (2015), Concerto for Oboe and Strings with Percussions, Op.6 (2004), Concerto for Cello and String Orchestra with Percussion, Op.18 (2009) and Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op 40 (2014). Concerto Grosso No. 1, Op.28 for Clarinet, Violin, Viola, Cello, Piano and String Orchestra with Percussion (2011) Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) 3 Romances for Viola and Strings with Harp (2009) Elvira Misbakhova (viola)/Evgeny Bushko/Belarusian State Chamber Orchestra ( + Concerto Grosso No. 1 and Letter from an Unknown Woman) CHANDOS CHAN20141 (2019) ARSHAK IKILIKIAN (b. 1948, ARMENIA) Born in Gyumri Armenia. -

New Approaches to Performance and the Practical

New Approaches to Performance and the Practical Application of Techniques from Non-Western and Electro-acoustic Musics in Compositions for Solo Cello since 1950: A Personal Approach and Two Case Studies Rebecca Turner Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of PhD in Music (Performance Practice) Department of Music Goldsmiths College, University of London 2014 Supervisor Professor Alexander Ivashkin Declaration I, Rebecca Turner, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work submitted in this thesis is my own and where the contributions of others are made they are clearly acknowledged. Signed……………………………………………… Date…………………….. Rebecca Turner ii For Alexander Ivashkin, 1948-2014 iii Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge the wisdom, encouragement, and guidance from my academic supervisor, the late Professor Alexander Ivashkin; it was an honour and a privilege to be his student. I am also eternally grateful for the tutelage of my performance supervisor, Natalia Pavlutskaya, for her support and encouragement over the years; she has taught me to always strive for excellence in all areas of my life. I am enormously grateful to Franghiz Ali-Zadeh and Michael Cryne for allowing me to feature their compositions in my case studies, and also for generosity giving up their time for our interviews. I am indebted to the staff of the Music Department at Goldsmiths College, London University, both for supporting me in my research and also being so generous with the use of the available facilities; in particular the Stanley Glasser Electronic Music Studios. I also thank C.f. Peters Corp., Breitkopf & Härtel, Schott Music Ltd, MUSIKVERLA HANS SIKORSKI GMBH & CO, for their kind permission to quote from copyrighted material. -

Cello Concerto (1990)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET CONCERTOS A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Edited by Stephen Ellis Composers A-G RUSTAM ABDULLAYEV (b. 1947, UZBEKISTAN) Born in Khorezm. He studied composition at the Tashkent Conservatory with Rumil Vildanov and Boris Zeidman. He later became a professor of composition and orchestration of the State Conservatory of Uzbekistan as well as chairman of the Composers' Union of Uzbekistan. He has composed prolifically in most genres including opera, orchestral, chamber and vocal works. He has completed 4 additional Concertos for Piano (1991, 1993, 1994, 1995) as well as a Violin Concerto (2009). Piano Concerto No. 1 (1972) Adiba Sharipova (piano)/Z. Khaknazirov/Uzbekistan State Symphony Orchestra ( + Zakirov: Piano Concerto and Yanov-Yanovsky: Piano Concertino) MELODIYA S10 20999 001 (LP) (1984) LEV ABELIOVICH (1912-1985, BELARUS) Born in Vilnius, Lithuania. He studied at the Warsaw Conservatory and then at the Minsk Conservatory where his composition teacher was Vasily Zolataryov. After graduation from the latter institution, he took further composition courses with Nikolai Miaskovsky at the Moscow Conservatory. He composed orchestral, vocal and chamber works. Piano Concerto in E minor (1976) Alexander Tutunov (piano)/ Marlan Carlson/Corvallis-Oregon State University Symphony Orchestra ( + Piano Trio, Aria for Viola and Piano and 10 Romances) ALTARUS 9058 (2003) Aria for Violin and Chamber Orchestra (1973) Mikhail Shtein (violin)/Alexander Polyanko/Minsk Chamber Orchestra ( + Vagner: Clarinet Concerto and Alkhimovich: Concerto Grosso No. 2) MELODIYA S10 27829 003 (LP) (1988) MusicWeb International Last updated: August 2020 Russian, Soviet & Post-Soviet Concertos A-G ISIDOR ACHRON (1891-1948) Piano Concerto No. -

BCSBC Newsletter May 2007

Issue 5 Vancouver, Canada May 16, 2007 www.bcsbc.ca This issue is dedicated to May 24, The Day of the Bulgarian Enlightenment and Culture, and of the Slavonic Alphabet Happy Holiday! The Bulgarian-Canadian Society of British Columbia congratulates all Bulgarians on the occasion of Mays 24, the Day of the Bulgarian Enlightenment and Culture, and of the Slavonic Alphabet! One of the most exciting holidays of our people, this day in the beautiful month of May fills us every year with a grandiose sense of pride, patriotism, and national dignity. It gives us a feeling of enlightenment and hope for spiritual strength, for light and uplifting in harmony with the unique colors and happy sounds of spring. Man and nature look up to new heights and start dreaming of something endless, magnetic, and stronger than themselves. Nature turns to the sun, and we turn to the inner light in our lives – speech, knowledge, science, and culture. Let us have a happy holiday and let this magnificent day continue to charge us with energy, love for the word, faith in its strenghth and intuition how we can use it to make our days brighter and worthier. Ivelina Tchizmarova, Ph.D. Director in the Bulgarian-Canadian Society of British Columbia and editor in chief of the BCSBC Newsletter Successful Bulgarians in Vancouver: Anna Levy – a piano player, a teacher, and a patriot The first impression Anna Levy leaves in people is “genuine, warm, down-to-earth”. Before one knows her, one may think that musicians of her caliber are more haughty and inaccessible, but I did not find anything of this stereotype in the Bulgarian virtuoso.