Baasha of Ammon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thiele's Biblical Chronology As a Corrective for Extrabiblical Dates

Andm University Seminary Studies, Autumn 1996, Vol. 34, No. 2,295-317. Copyright 1996 by Andrews University Press.. THIELE'S BIBLICAL CHRONOLOGY AS A CORRECTIVE FOR EXTRABIBLICAL DATES KENNETH A. STRAND Andrews University The outstanding work of Edwin R. Thiele in producing a coherent and internally consistent chronology for the period of the Hebrew Divided Monarchy is well known. By ascertaining and applying the principles and procedures used by the Hebrew scribes in recording the lengths of reign and synchronisms given in the OT books of Kings and Chronicles for the kings of Israel and Judah, he was able to demonstrate the accuracy of these biblical data. What has generally not been given due notice is the effect that Thiele's clarification of the Hebrew chronology of this period of history has had in furnishing a corrective for various dates in ancient Assyrian and Babylonian history. It is the purpose of this essay to look at several such dates.' 1. i%e Basic Question In a recent article in AUSS, Leslie McFall, who along with many other scholars has shown favor for Thiele's chronology, notes five vital variable factors which Thiele recognized, and then he sets forth the following opinion: In view of the complex interaction of several of the independent factors, it is clear that such factors could never have been discovered (or uncovered) if it had not been for extrabiblical evidence which established certain key absolute dates for events in Israel and Judah, such as 853, 841, 723, 701, 605, 597, and 586 B.C. It was as a result of trial and error in fitting the biblical data around these absolute dates that previous chronologists (and more recently Thiele) brought to light the factors outlined above.= '~lthou~hmuch of the information provided in this article can be found in Thiele's own published works, the presentation given here gathers it, together with certain other data, into a context and with a perspective not hitherto considered, so far as I have been able to determine. -

09,David's Victories and Officers.Pdf

II Samuel 8:1-18 Lesson #9, David‟s victories and officers The Israelites were surrounded by powerful enemies who had a special hatred of their nation. David, like the Messiah after him must destroy all of his and his people‟s enemies (Lk 20:43). II Samuel 8 tells us of victorious wars against the Philistines, against Moab, against Zobah, against Syria, against Amalek, and against Edom. All these successful conquests are explained in this way: „The Lord gave victory to David wherever he went (II Samuel 8:6,14).1 8:1-14, These verses outline the expansion of David‟s kingdom under the hand of the Lord (v:6,14). Israel‟s major enemies were all defeated as David‟s kingdom extended N, S, E, and W. See I Chronicles 18:1-13. This conquering before the event of chap. 7 (see 7:1) MacArthur Study Bible II Sam 8:1, Now after this it came about that David [1.] v:1, chief city. According to I Chr 18:1, defeated the Philistines and subdued them; and What was probably the chief city of the David took control of the chief city (Metheg Philistines? Ammah) from the hand of the Philistines. 2 He defeated Moab, and measured them with the [2.] v:2, Find Moab on your map, page #4 line, making them lie down on the ground; and he and write a description of it‟s location measured two lines to put to death and one full line to keep alive. And the Moabites became servants to David, bringing tribute. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

THROUGH the BIBLE ISAIAH 15-19 in the Bible God Judges Individuals, and Families, and Churches, and Cities, and Even Nations…

THROUGH THE BIBLE ISAIAH 15-19 ! In the Bible God judges individuals, and families, and churches, and cities, and even nations… I would assume He also judges businesses, and labor unions, and school systems, and civic groups, and athletic associations - all of life is God’s domain. Starting in Isaiah 13, God launches a series of judgments against the Gentile nations of his day. Making Isaiah’s list are Babylon, Assyria, Philistia, Moab, Ethiopia, Egypt, Edom, Tyre, and Syria. Tonight we’ll study God’s burden against the nations. ! Isaiah 15 begins, “The burden against Moab…” Three nations bordered Israel to the east - Moab, Edom, and Ammon. Today this area makes up the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan - a pro-Western monarchy with its capitol city of Amman - or Ammon. ! Today, it’s fashionable to research your roots - track down the family tree. Websites like Ancestry.com utilize the power of the Internet to uncover your genealogy. For some folks this is a fun and meaningful pastime. For me, I’ve always been a little leery… I suspect I’m from a long line of horse thieves and swindlers. I’m not sure I want to know my ancestry. This is probably how most Moabites felt regarding their progenitors… ! The Moabites were a people with some definite skeletons in the closest! Their family tree had root rot. Recently, I read of a Michigan woman who gave her baby up for adoption. Sixteen years later she tracked him down on FB… only to get romantically involved. She had sex with her son… Obviously this gal is one sick pup. -

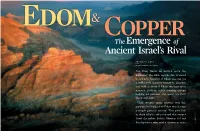

EDOM and COPPER Photo by Mohammad Najjar Mohammad by Photo Photo by Thomas E

Edom& Copper The Emergence of Ancient Israel’s Rival Thomas E. L E v y a n d m ohammad Najjar Did King David do battle with the Edomites? The Bible says he did. It would be unlikely, however, if Edom was not yet a sufficiently complex society to organize and field an army, if Edom was just some nomadic Bedouin tribes roaming around looking for pastures and water for their sheep and goats. Until recently, many scholars took this position: In David’s time Edom was at most a simple pastoral society.1 This gave fuel to those scholars who insisted that ancient DUBY TAL / Israel (or rather, Judah) likewise did not ALBATROSS develop into a state until a century or more 24 BI B LICA L ARCHAEOLOGY REVIEW • JULY/AUGUST 2006 JULY/AUGUST 2006 • BI B LICA L ARCHAEOLOGY REVIEW 25 EDOM AND COPPER PHOTO BY MOHAMMAD NAJJAR PHOTO BY THOMAS E. LEVY after David’s time. Ancient Israel, they argued, explore the role of early mining and metallurgy on r PILES OF RUBBLE (opposite) bestride the outline of a large e v was just like the situation east of the Jordan—no i square fortress and more than 100 smaller buildings at social evolution from the beginnings of agriculture R AMMON n complex societies in Ammon, Moab or Edom. a Khirbat en-Nahas in the Edomite lowlands of Jordan. The and sedentary village life from the Pre-pottery d r According to this school of thought, David was o Neolithic period (c. 8500 B.C.E.) to the Iron Age J massive black mounds are slag, a waste product of the Jerusalem not really a king, but a chieftain of a few simple SEA copper-smelting process, indicating that large-scale copper (1200–500 B.C.E.) in Jordan. -

MESHA STELE. Discovered at Dhiban in 1868 by a Protestant Missionary

MESHA STELE. Discovered at Dhiban in 1868 by a Protestant missionary traveling in Transjordan, the 35-line Mesha Inscription (hereafter MI, sometimes called the Moabite Stone) remains the longest-known royal inscription from the Iron Age discovered in the area of greater Palestine. As such, it has been examined repeatedly by scholars and is available in a number of modern translations (ANET, DOTT). Formally, the MI is like other royal inscriptions of a dedicatory nature from the period. Mesha, king of Moab, recounts the favor of Moab's chief deity, Chemosh (Kemosh), in delivering Moab from the control of its neighbor, Israel. While the MI contains considerable historical detail, formal parallels suggest the Moabite king was selective in arranging the sequence of events to serve his main purpose of honoring Chemosh. This purpose is indicated by lines 3-4 of the MI, where Mesha says that he erected the stele at the "high place" in Qarh\oh, which had been built to venerate Chemosh. The date of the MI can be set with a 20-30-year variance. It must have been written either just before the Israelite king Ahab's death (ca. 853/852 B.C.) or a decade or so after his demise. The reference to Ahab is indicated by the reference in line 8 to Omri's "son," or perhaps "sons" (unfortunately, without some additional information, it is impossible to tell morphologically whether the word [bnh] is singular or plural). Ahab apparently died not long after the battle of Qarqar, in the spring of 853, when a coalition of states in S Syria/Palestine, of which Ahab was a leader, faced the encroaching Assyrians under Shalmaneser III. -

The Names and Boundaries of Eretz-Israel (Palestine) As Reflections of Stages in Its History

THE NAMES AND BOUNDARIES OF ERETZ-ISRAEL (PALESTINE) AS REFLECTIONS OF STAGES IN ITS HISTORY GIDEON BIGER INTRODUCTION Classical historical geography focuses on research of the boundaries of the various states, along with the historical development of these boundaries over time. Edward Freeman, in his book written in 1881 and entitled The Historical Geography of Europe, defines the nature of historical-geographical research as follows: "The work which we have now before us is to trace out the extent of territory which the different states and nations have held at different times in the world's history, to mark the different boundaries which the same country has had and the different meanings in which the same name has been used." The author further claims that "it is of great importance carefully to make these distinctions, because great mistakes as to the facts of history are often caused through men thinking and speaking as if the names of different countries have always meant exactly the same extent of territory. "1 Although this approach - which regards research on boundaries as the essence of historical geography- is not accepted at present, the claim that it is necessary to define the extent of territory over history is as valid today as ever. It is impossible to discuss the development of any geographical area having political and territorial significance without knowing and understanding its physical extent. Of no less significance for such research are the names attached to any particular expanse. The naming of a place is the first step in defining it politically and historically. -

The Iniquities of Ammon and Moab

THE INIQUITIES OF AMMON AND MOAB REUVEN CHAIM (RUDOLPH) KLEIN When barring Ammonites and Moabites from marrying Israelites, the To- rah says: An Ammonite or a Moabite shall not enter into the assembly of the Lord; even to the tenth generation shall none of them enter into the assembly of the Lord for ever; because they met you not with bread and with water on the way, when you came forth out of Egypt; and because they hired against you Balaam the son of Beor from Pethor of Aram-naharaim (Deut. 23:4-5). This passage explicitly states that the Ammonites and Moabites are to be ostracized because they met you not with bread and with water on the way, when you came forth out of Egypt. However, another passage in Deuterono- my seems to contradict this. When Moses requested permission from Sihon king of Heshbon to pass through his land and buy food and water, he sup- ported his request by noting that the Edomites (the children of Esau) and the Moabites had already allowed the Israelites to do so. Moses said: 'Thou shalt sell me food for money, that I may eat; and give me water for money, that I may drink; only let me pass through on my feet; as the children of Esau that dwell in Seir, and the Moabites that dwell in Ar, did unto me; until I shall pass over the Jordan into the land which the Lord our God giveth us' (Deut. 2:28-29). This contradicts the assertion above that the Moabites met you not with bread and with water. -

"The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah." Israel and Empire: a Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism

"The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah." Israel and Empire: A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism. Perdue, Leo G., and Warren Carter.Baker, Coleman A., eds. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2015. 37–68. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9780567669797.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 16:38 UTC. Copyright © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 The Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah I. Historical Introduction1 When the installation of a new monarch in the temple of Ashur occurs during the Akitu festival, the Sangu priest of the high god proclaims when the human ruler enters the temple: Ashur is King! Ashur is King! The ruler now is invested with the responsibilities of the sovereignty, power, and oversight of the Assyrian Empire. The Assyrian Empire has been described as a heterogeneous multi-national power directed by a superhuman, autocratic king, who was conceived of as the representative of God on earth.2 As early as Naram-Sin of Assyria (ca. 18721845 BCE), two important royal titulars continued and were part of the larger titulary of Assyrian rulers: King of the Four Quarters and King of All Things.3 Assyria began its military advances west to the Euphrates in the ninth century BCE. -

National Museum of Aleppo As a Model)

Strategies for reconstructing and restructuring of museums in post-war places (National Museum of Aleppo as a Model) A dissertation submitted at the Faculty of Philosophy and History at the University of Bern for the doctoral degree by: Mohamad Fakhro (Idlib – Syria) 20/02/2020 Prof. Dr. Mirko Novák, Institut für Archäologische Wissenschaften der Universität Bern and Dr. Lutz Martin, Stellvertretender Direktor, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin Fakhro. Mohamad Hutmatten Str.12 D-79639 Grenzach-Wyhlen Bern, 25.11.2019 Original document saved on the web server of the University Library of Bern This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No derivative works 2.5 Switzerland licence. To see the licence go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ or write to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California 94105, USA Copyright Notice This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No derivative works 2.5 Switzerland. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ You are free: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work Under the following conditions: Attribution. You must give the original author credit. Non-Commercial. You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No derivative works. You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.. For any reuse or distribution, you must take clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Nothing in this license impairs or restricts the author’s moral rights according to Swiss law. -

Legacies of the Anglo-Hashemite Relationship in Jordan

Legacies of the Anglo-Hashemite Relationship in Jordan: How this symbiotic alliance established the legitimacy and political longevity of the regime in the process of state-formation, 1914-1946 An Honors Thesis for the Department of Middle Eastern Studies Julie Murray Tufts University, 2018 Acknowledgements The writing of this thesis was not a unilateral effort, and I would be remiss not to acknowledge those who have helped me along the way. First of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Thomas Abowd, for his encouragement of my academic curiosity this past year, and for all his help in first, making this project a reality, and second, shaping it into (what I hope is) a coherent and meaningful project. His class provided me with a new lens through which to examine political history, and gave me with the impetus to start this paper. I must also acknowledge the role my abroad experience played in shaping this thesis. It was a research project conducted with CET that sparked my interest in political stability in Jordan, so thank you to Ines and Dr. Saif, and of course, my classmates, Lensa, Matthew, and Jackie, for first empowering me to explore this topic. I would also like to thank my parents and my brother, Jonathan, for their continuous support. I feel so lucky to have such a caring family that has given me the opportunity to pursue my passions. Finally, a shout-out to the gals that have been my emotional bedrock and inspiration through this process: Annie, Maya, Miranda, Rachel – I love y’all; thanks for listening to me rant about this all year. -

The Period of the Kings Is the Third Stage in Israel's History. It Follows

441 The period of the kings is the third stage in Israel’s history. It follows the period of the Patriarchs (Abraham in the year 1750 B.C.) and that of the Exodus and the Conquest (Moses in the year 1250 B.C.). David captured Jerusalem around the year 1000 B.C. After Solomon’s death in the year 932 B.C., the kingdom of David and his son Solomon would be divided. The northern part, called the kingdom of Israel, would cease to exist as a nation two centuries later. The southern part, called the kingdom of Judah, would last until the year 587 B.C., the year of the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple, and of the Exile to Babylon. This period covers a total of four centuries. These four centuries of the kings are the most important in sacred history because this is the period during which God raised up prophets from among his people. The greater part of Scripture was written during those four centuries. It was not only the major prophets who produced writings, e.g., Isaiah and Jeremiah. There 1-2 K were also groups of prophets of lesser importance who wrote much of Israel’s his- tory, such as the greater part of the pages of Genesis and Exodus, the Books of Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings. We can say that the period of the kings is the most important period in sacred history. It is also the time which we know with the greatest precision. These four centuries would appear to be the time of the kingdom of Israel’s deca- dence if we paid attention only to its wealth and power.