Antichains in the Set of Subsets of a Multiset I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion

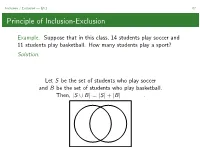

Inclusion / Exclusion — §3.1 67 Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion Example. Suppose that in this class, 14 students play soccer and 11 students play basketball. How many students play a sport? Solution. Let S be the set of students who play soccer and B be the set of students who play basketball. Then, |S ∪ B| = |S| + |B| . Inclusion / Exclusion — §3.1 68 Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion When A = A1 ∪···∪Ak ⊂U (U for universe) and the sets Ai are pairwise disjoint,wehave|A| = |A1| + ···+ |Ak |. When A = A1 ∪···∪Ak ⊂U and the Ai are not pairwise disjoint, we must apply the principle of inclusion-exclusion to determine |A|: |A1 ∪ A2| = |A1| + |A2|−|A1 ∩ A2| |A1 ∪ A2 ∪ A3| = |A1| + |A2| + |A3|−|A1 ∩ A2|−|A1 ∩ A3| −|A2 ∩ A3| + |A1 ∩ A2 ∩ A3| |A1 ∪···∪Am| = |Ai |− |Ai ∩ Aj | + Ai ∩ Aj ∩ Ak ··· ! ! ! " " " " It may be more convenient to apply inclusion/exclusion where the Ai are forbidden subsets of U,inwhichcase . Inclusion / Exclusion — §3.1 69 mmm...PIE The key to using the principle of inclusion-exclusion is determining the right choice of Ai .TheAi and their intersections should be easy to count and easy to characterize. Notation: π = p1p2 ···pn is the one-line notation for a permutation of [n] whose first element is p1,secondelementisp2,etc. Example. How many permutations p = p1p2 ···pn are there in which at least one of p1 and p2 are even? Solution. Let U be the set of n-permutations. Let A1 be the set of permutations where p1 is even. Let A2 be the set of permutations where p2 is even. -

MTH 102A - Part 1 Linear Algebra 2019-20-II Semester

MTH 102A - Part 1 Linear Algebra 2019-20-II Semester Arbind Kumar Lal1 February 3, 2020 1Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur 1 2 • Matrix A = behaves like the scalar 3 when multiplied with 2 1 1 1 2 1 1 x = . That is, = 3 . 1 2 1 1 1 • Physically: The Linear function f (x) = Ax magnifies the nonzero 1 2 vector ∈ C three (3) times. 1 1 1 • Similarly, A = −1 . So, behaves by changing the −1 −1 1 direction of the vector −1 1 2 2 • Take A = . Do I have a nonzero x ∈ C which gets 1 3 magnified by A? • So I am looking for x 6= 0 and α s.t. Ax = αx. Using x 6= 0, we have Ax = αx if and only if [αI − A]x = 0 if and only if det[αI − A] = 0. √ α − 1 −2 2 • det[αI − A] = det = α − 4α + 1. So α = 2 ± 3. −1 α − 3 √ √ 1 + 3 −2 • Take α = 2 + 3. To find x, solve √ x = 0: −1 3 − 1 √ 3 − 1 using GJE, for instance. We get x = . Moreover 1 √ √ √ 1 2 3 − 1 3 + 1 √ 3 − 1 Ax = = √ = (2 + 3) . 1 3 1 2 + 3 1 n • We call λ ∈ C an eigenvalue of An×n if there exists x ∈ C , x 6= 0 s.t. Ax = λx. We call x an eigenvector of A for the eigenvalue λ. We call (λ, x) an eigenpair. • If (λ, x) is an eigenpair of A, then so is (λ, cx), for each c 6= 0, c ∈ C. -

Inclusion‒Exclusion Principle

Inclusionexclusion principle 1 Inclusion–exclusion principle In combinatorics, the inclusion–exclusion principle (also known as the sieve principle) is an equation relating the sizes of two sets and their union. It states that if A and B are two (finite) sets, then The meaning of the statement is that the number of elements in the union of the two sets is the sum of the elements in each set, respectively, minus the number of elements that are in both. Similarly, for three sets A, B and C, This can be seen by counting how many times each region in the figure to the right is included in the right hand side. More generally, for finite sets A , ..., A , one has the identity 1 n This can be compactly written as The name comes from the idea that the principle is based on over-generous inclusion, followed by compensating exclusion. When n > 2 the exclusion of the pairwise intersections is (possibly) too severe, and the correct formula is as shown with alternating signs. This formula is attributed to Abraham de Moivre; it is sometimes also named for Daniel da Silva, Joseph Sylvester or Henri Poincaré. Inclusion–exclusion illustrated for three sets For the case of three sets A, B, C the inclusion–exclusion principle is illustrated in the graphic on the right. Proof Let A denote the union of the sets A , ..., A . To prove the 1 n Each term of the inclusion-exclusion formula inclusion–exclusion principle in general, we first have to verify the gradually corrects the count until finally each identity portion of the Venn Diagram is counted exactly once. -

Multipermutations 1.1. Generating Functions

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector JOURNALOF COMBINATORIALTHEORY, Series A 67, 44-71 (1994) The r- Multipermutations SEUNGKYUNG PARK Department of Mathematics, Yonsei University, Seoul 120-749, Korea Communicated by Gian-Carlo Rota Received October 1, 1992 In this paper we study permutations of the multiset {lr, 2r,...,nr}, which generalizes Gesse| and Stanley's work (J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 24 (1978), 24-33) on certain permutations on the multiset {12, 22..... n2}. Various formulas counting the permutations by inversions, descents, left-right minima, and major index are derived. © 1994 AcademicPress, Inc. 1. THE r-MULTIPERMUTATIONS 1.1. Generating Functions A multiset is defined as an ordered pair (S, f) where S is a set and f is a function from S to the set of nonnegative integers. If S = {ml ..... mr}, we write {m f(mD, .... m f(mr)r } for (S, f). Intuitively, a multiset is a set with possibly repeated elements. Let us begin by considering permutations of multisets (S, f), which are words in which each letter belongs to the set S and for each m e S the total number of appearances of m in the word is f(m). Thus 1223231 is a permutation of the multiset {12, 2 3, 32}. In this paper we consider a special set of permutations of the multiset [n](r) = {1 r, ..., nr}, which is defined as follows. DEFINITION 1.1. An r-multipermutation of the set {ml ..... ran} is a permutation al ""am of the multiset {m~ .... -

Basic Operations for Fuzzy Multisets

Basic operations for fuzzy multisets A. Riesgoa, P. Alonsoa, I. D´ıazb, S. Montesc aDepartment of Mathematics, University of Oviedo, Spain bDepartment of Informatics, University of Oviedo, Spain cDepartment of Statistics and O.R., University of Oviedo, Spain Abstract In their original and ordinary formulation, fuzzy sets associate each element in a reference set with one number, the membership value, in the real unit interval [0; 1]. Among the various existing generalisations of the concept, we find fuzzy multisets. In this case, membership values are multisets in [0; 1] rather than single values. Mathematically, they can be also seen as a generalisation of the hesitant fuzzy sets, but in this general environment, the information about repetition is not lost, so that, the opinions given by the experts are better managed. Thus, we focus our study on fuzzy multisets and their basic operations: complement, union and intersection. Moreover, we show how the hesitant operations can be worked out from an extension of the fuzzy multiset operations and investigate the important role that the concepts of order and sorting sequences play in the basic difference between these two related approaches. Keywords: Fuzzy multiset; Hesitant fuzzy set; Complement; Aggregate union; Aggregate intersection. 1. Introduction The concept of a fuzzy set was originally introduced by Lotfi A. Zadeh as an extension of classical set theory [15]. Fuzzy sets aim to account for real-life situations where there is either limited knowledge or some sort of implicit ambiguity about whether an element should be considered a member of a set. This extension from the classical (or crisp) sets to the fuzzy ones is accomplished by replacing the Boolean characteristic function of a set, which maps each element of the universal set to either 0 (non-member) or 1 (member), with a more sophisticated membership function that maps elements into the real interval [0; 1]. -

Finding Direct Partition Bijections by Two-Directional Rewriting Techniques

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Discrete Mathematics 285 (2004) 151–166 www.elsevier.com/locate/disc Finding direct partition bijections by two-directional rewriting techniques Max Kanovich Department of Computer and Information Science, University of Pennsylvania, 3330 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA Received 7 May 2003; received in revised form 27 October 2003; accepted 21 January 2004 Abstract One basic activity in combinatorics is to establish combinatorial identities by so-called ‘bijective proofs,’ which consists in constructing explicit bijections between two types of the combinatorial objects under consideration. We show how such bijective proofs can be established in a systematic way from the ‘lattice properties’ of partition ideals, and how the desired bijections are computed by means of multiset rewriting, for a variety of combinatorial problems involving partitions. In particular, we fully characterizes all equinumerous partition ideals with ‘disjointly supported’ complements. This geometrical characterization is proved to automatically provide the desired bijection between partition ideals but in terms of the minimal elements of the order ÿlters, their complements. As a corollary, a new transparent proof, the ‘bijective’ one, is given for all equinumerous classes of the partition ideals of order 1 from the classical book “The Theory of Partitions” by G.Andrews. Establishing the required bijections involves two-directional reductions technique novel in the sense that forward and backward application of rewrite rules heads, respectively, for two di?erent normal forms (representing the two combinatorial types). It is well-known that non-overlapping multiset rules are con@uent. -

Symmetric Relations and Cardinality-Bounded Multisets in Database Systems

Symmetric Relations and Cardinality-Bounded Multisets in Database Systems Kenneth A. Ross Julia Stoyanovich Columbia University¤ [email protected], [email protected] Abstract 1 Introduction A relation R is symmetric in its ¯rst two attributes if R(x ; x ; : : : ; x ) holds if and only if R(x ; x ; : : : ; x ) In a binary symmetric relationship, A is re- 1 2 n 2 1 n holds. We call R(x ; x ; : : : ; x ) the symmetric com- lated to B if and only if B is related to A. 2 1 n plement of R(x ; x ; : : : ; x ). Symmetric relations Symmetric relationships between k participat- 1 2 n come up naturally in several contexts when the real- ing entities can be represented as multisets world relationship being modeled is itself symmetric. of cardinality k. Cardinality-bounded mul- tisets are natural in several real-world appli- Example 1.1 In a law-enforcement database record- cations. Conventional representations in re- ing meetings between pairs of individuals under inves- lational databases su®er from several consis- tigation, the \meets" relationship is symmetric. 2 tency and performance problems. We argue that the database system itself should pro- Example 1.2 Consider a database of web pages. The vide native support for cardinality-bounded relationship \X is linked to Y " (by either a forward or multisets. We provide techniques to be im- backward link) between pairs of web pages is symmet- plemented by the database engine that avoid ric. This relationship is neither reflexive nor antire- the drawbacks, and allow a schema designer to flexive, i.e., \X is linked to X" is neither universally simply declare a table to be symmetric in cer- true nor universally false. -

An Overview of the Applications of Multisets1

Novi Sad J. Math. Vol. 37, No. 2, 2007, 73-92 AN OVERVIEW OF THE APPLICATIONS OF MULTISETS1 D. Singh2, A. M. Ibrahim2, T. Yohanna3 and J. N. Singh4 Abstract. This paper presents a systemization of representation of multisets and basic operations under multisets, and an overview of the applications of multisets in mathematics, computer science and related areas. AMS Mathematics Subject Classi¯cation (2000): 03B65, 03B70, 03B80, 68T50, 91F20 Key words and phrases: Multisets, power multisets, dressed epsilon sym- bol, multiset ordering, Dershowtiz-Mana ordering 1. Introduction A multiset (mset, for short) is an unordered collection of objects (called the elements) in which, unlike a standard (Cantorian) set, elements are allowed to repeat. In other words, an mset is a set to which elements may belong more than once, and hence it is a non-Cantorian set. In this paper, we endeavour to present an overview of basics of multiset and applications. The term multiset, as Knuth ([46], p. 36) notes, was ¯rst suggested by N.G.de Bruijn in a private communication to him. Owing to its aptness, it has replaced a variety of terms, viz. list, heap, bunch, bag, sample, weighted set, occurrence set, and ¯reset (¯nitely repeated element set) used in di®erent contexts but conveying synonimity with mset. As mentioned earlier, elements are allowed to repeat in an mset (¯nitely in most of the known application areas, albeit in a theoretical development in¯nite multiplicities of elements are also dealt with (see [11], [37], [51], [72] and [30], in particular). The number of copies (([17], P. -

Week 3-4: Permutations and Combinations

Week 3-4: Permutations and Combinations March 10, 2020 1 Two Counting Principles Addition Principle. Let S1;S2;:::;Sm be disjoint subsets of a ¯nite set S. If S = S1 [ S2 [ ¢ ¢ ¢ [ Sm, then jSj = jS1j + jS2j + ¢ ¢ ¢ + jSmj: Multiplication Principle. Let S1;S2;:::;Sm be ¯nite sets and S = S1 £ S2 £ ¢ ¢ ¢ £ Sm. Then jSj = jS1j £ jS2j £ ¢ ¢ ¢ £ jSmj: Example 1.1. Determine the number of positive integers which are factors of the number 53 £ 79 £ 13 £ 338. The number 33 can be factored into 3 £ 11. By the unique factorization theorem of positive integers, each factor of the given number is of the form 3i £ 5j £ 7k £ 11l £ 13m, where 0 · i · 8, 0 · j · 3, 0 · k · 9, 0 · l · 8, and 0 · m · 1. Thus the number of factors is 9 £ 4 £ 10 £ 9 £ 2 = 7280: Example 1.2. How many two-digit numbers have distinct and nonzero digits? A two-digit number ab can be regarded as an ordered pair (a; b) where a is the tens digit and b is the units digit. The digits in the problem are required to satisfy a 6= 0; b 6= 0; a 6= b: 1 The digit a has 9 choices, and for each ¯xed a the digit b has 8 choices. So the answer is 9 £ 8 = 72. The answer can be obtained in another way: There are 90 two-digit num- bers, i.e., 10; 11; 12;:::; 99. However, the 9 numbers 10; 20;:::; 90 should be excluded; another 9 numbers 11; 22;:::; 99 should be also excluded. So the answer is 90 ¡ 9 ¡ 9 = 72. -

Essential Spectral Theory, Hall's Spectral Graph Drawing, the Fiedler

Spectral Graph Theory Lecture 2 Essential spectral theory, Hall's spectral graph drawing, the Fiedler value Daniel A. Spielman August 31, 2018 2.1 Eigenvalues and Optimization The Rayleigh quotient of a vector x with respect to a matrix M is defined to be x T M x : x T x At the end of the last class, I gave the following characterization of the largest eigenvalue of a symmetric matrix in terms of the Rayleigh quotient. Theorem 2.1.1. Let M be a symmetric matrix and let x be a non-zero vector that maximizes the Rayleigh quotient with respect to M : x T M x : x T x Then, x is an eigenvector of M with eigenvalue equal to the Rayleigh quotient. Moreover, this eigenvalue is the largest eigenvalue of M . Proof. We first observe that the maximum is achieved: As the Rayleigh quotient is homogeneous, it suffices to consider unit vectors x. As the set of unit vectors is a closed and compact set, the maximum is achieved on this set. Now, let x be a non-zero vector that maximizes the Rayleigh quotient. We recall that the gradient of a function at its maximum must be the zero vector. Let's compute that gradient. We have rx T x = 2x; and rx T M x = 2M x: So, x T M x (x T x)(2M x) − (x T M x)(2x) r = : x T x (x T x)2 In order for this to be zero, we must have x T M x M x = x: x T x That is, if and only if x is an eigenvector of M with eigenvalue equal to its Rayleigh quotient. -

Lecture 1.1: Basic Set Theory

Lecture 1.1: Basic set theory Matthew Macauley Department of Mathematical Sciences Clemson University http://www.math.clemson.edu/~macaule/ Math 4190, Discrete Mathematical Structures M. Macauley (Clemson) Lecture 1.1: Basic set theory Discrete Mathematical Structures 1 / 14 What is a set? Almost everybody, regardless of mathematical background, has an intiutive idea of what a set is: a collection of objects, sometimes called elements. Sets can be finite or infinite. Examples of sets 1. Let S be the set consisting of 0 and 1. We write S = f0; 1g. 2. Let S be the set of words in the dictionary. 3. Let S = ;, the \empty set". 4. Let S = f2; A; cat; f0; 1gg. Repeated elements in sets are not allowed. In other words, f1; 2; 3; 3g = f1; 2; 3g. If we want to allow repeats, we can use a related object called a multiset. Perhaps surprisingly, it is very difficult to formally define what a set is. The problem is that some sets actually cannot exist! For example, if we try to define the set of all sets, we will run into a problem called a paradox. M. Macauley (Clemson) Lecture 1.1: Basic set theory Discrete Mathematical Structures 2 / 14 Russell's paradox The following is called Russell's paradox, due to British philsopher, logician, and mathematician Bertrand Russell (1872{1970): Suppose a town's barber shaves every man who doesn't shave himself. Who shaves the barber? Now, consider the set S of all sets which do not contain themselves. Does S contain itself? Later this class, we will encounter paradoxes that are not related to sets, but logical statements, such as: This statement is false. -

Set (Mathematics) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Set (mathematics) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A set in mathematics is a collection of well defined and distinct objects, considered as an object in its own right. Sets are one of the most fundamental concepts in mathematics. Developed at the end of the 19th century, set theory is now a ubiquitous part of mathematics, and can be used as a foundation from which nearly all of mathematics can be derived. In mathematics education, elementary topics such as Venn diagrams are taught at a young age, while more advanced concepts are taught as part of a university degree. Contents The intersection of two sets is made up of the objects contained in 1 Definition both sets, shown in a Venn 2 Describing sets diagram. 3 Membership 3.1 Subsets 3.2 Power sets 4 Cardinality 5 Special sets 6 Basic operations 6.1 Unions 6.2 Intersections 6.3 Complements 6.4 Cartesian product 7 Applications 8 Axiomatic set theory 9 Principle of inclusion and exclusion 10 See also 11 Notes 12 References 13 External links Definition A set is a well defined collection of objects. Georg Cantor, the founder of set theory, gave the following definition of a set at the beginning of his Beiträge zur Begründung der transfiniten Mengenlehre:[1] A set is a gathering together into a whole of definite, distinct objects of our perception [Anschauung] and of our thought – which are called elements of the set. The elements or members of a set can be anything: numbers, people, letters of the alphabet, other sets, and so on.