§3.4–3.5 Permutations and Combinations of Multisets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion

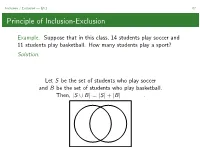

Inclusion / Exclusion — §3.1 67 Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion Example. Suppose that in this class, 14 students play soccer and 11 students play basketball. How many students play a sport? Solution. Let S be the set of students who play soccer and B be the set of students who play basketball. Then, |S ∪ B| = |S| + |B| . Inclusion / Exclusion — §3.1 68 Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion When A = A1 ∪···∪Ak ⊂U (U for universe) and the sets Ai are pairwise disjoint,wehave|A| = |A1| + ···+ |Ak |. When A = A1 ∪···∪Ak ⊂U and the Ai are not pairwise disjoint, we must apply the principle of inclusion-exclusion to determine |A|: |A1 ∪ A2| = |A1| + |A2|−|A1 ∩ A2| |A1 ∪ A2 ∪ A3| = |A1| + |A2| + |A3|−|A1 ∩ A2|−|A1 ∩ A3| −|A2 ∩ A3| + |A1 ∩ A2 ∩ A3| |A1 ∪···∪Am| = |Ai |− |Ai ∩ Aj | + Ai ∩ Aj ∩ Ak ··· ! ! ! " " " " It may be more convenient to apply inclusion/exclusion where the Ai are forbidden subsets of U,inwhichcase . Inclusion / Exclusion — §3.1 69 mmm...PIE The key to using the principle of inclusion-exclusion is determining the right choice of Ai .TheAi and their intersections should be easy to count and easy to characterize. Notation: π = p1p2 ···pn is the one-line notation for a permutation of [n] whose first element is p1,secondelementisp2,etc. Example. How many permutations p = p1p2 ···pn are there in which at least one of p1 and p2 are even? Solution. Let U be the set of n-permutations. Let A1 be the set of permutations where p1 is even. Let A2 be the set of permutations where p2 is even. -

MTH 102A - Part 1 Linear Algebra 2019-20-II Semester

MTH 102A - Part 1 Linear Algebra 2019-20-II Semester Arbind Kumar Lal1 February 3, 2020 1Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur 1 2 • Matrix A = behaves like the scalar 3 when multiplied with 2 1 1 1 2 1 1 x = . That is, = 3 . 1 2 1 1 1 • Physically: The Linear function f (x) = Ax magnifies the nonzero 1 2 vector ∈ C three (3) times. 1 1 1 • Similarly, A = −1 . So, behaves by changing the −1 −1 1 direction of the vector −1 1 2 2 • Take A = . Do I have a nonzero x ∈ C which gets 1 3 magnified by A? • So I am looking for x 6= 0 and α s.t. Ax = αx. Using x 6= 0, we have Ax = αx if and only if [αI − A]x = 0 if and only if det[αI − A] = 0. √ α − 1 −2 2 • det[αI − A] = det = α − 4α + 1. So α = 2 ± 3. −1 α − 3 √ √ 1 + 3 −2 • Take α = 2 + 3. To find x, solve √ x = 0: −1 3 − 1 √ 3 − 1 using GJE, for instance. We get x = . Moreover 1 √ √ √ 1 2 3 − 1 3 + 1 √ 3 − 1 Ax = = √ = (2 + 3) . 1 3 1 2 + 3 1 n • We call λ ∈ C an eigenvalue of An×n if there exists x ∈ C , x 6= 0 s.t. Ax = λx. We call x an eigenvector of A for the eigenvalue λ. We call (λ, x) an eigenpair. • If (λ, x) is an eigenpair of A, then so is (λ, cx), for each c 6= 0, c ∈ C. -

An Exploration of the Relationship Between Mathematics and Music

An Exploration of the Relationship between Mathematics and Music Shah, Saloni 2010 MIMS EPrint: 2010.103 Manchester Institute for Mathematical Sciences School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Reports available from: http://eprints.maths.manchester.ac.uk/ And by contacting: The MIMS Secretary School of Mathematics The University of Manchester Manchester, M13 9PL, UK ISSN 1749-9097 An Exploration of ! Relation"ip Between Ma#ematics and Music MATH30000, 3rd Year Project Saloni Shah, ID 7177223 University of Manchester May 2010 Project Supervisor: Professor Roger Plymen ! 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface! 3 1.0 Music and Mathematics: An Introduction to their Relationship! 6 2.0 Historical Connections Between Mathematics and Music! 9 2.1 Music Theorists and Mathematicians: Are they one in the same?! 9 2.2 Why are mathematicians so fascinated by music theory?! 15 3.0 The Mathematics of Music! 19 3.1 Pythagoras and the Theory of Music Intervals! 19 3.2 The Move Away From Pythagorean Scales! 29 3.3 Rameau Adds to the Discovery of Pythagoras! 32 3.4 Music and Fibonacci! 36 3.5 Circle of Fifths! 42 4.0 Messiaen: The Mathematics of his Musical Language! 45 4.1 Modes of Limited Transposition! 51 4.2 Non-retrogradable Rhythms! 58 5.0 Religious Symbolism and Mathematics in Music! 64 5.1 Numbers are God"s Tools! 65 5.2 Religious Symbolism and Numbers in Bach"s Music! 67 5.3 Messiaen"s Use of Mathematical Ideas to Convey Religious Ones! 73 6.0 Musical Mathematics: The Artistic Aspect of Mathematics! 76 6.1 Mathematics as Art! 78 6.2 Mathematical Periods! 81 6.3 Mathematics Periods vs. -

18.703 Modern Algebra, Permutation Groups

5. Permutation groups Definition 5.1. Let S be a set. A permutation of S is simply a bijection f : S −! S. Lemma 5.2. Let S be a set. (1) Let f and g be two permutations of S. Then the composition of f and g is a permutation of S. (2) Let f be a permutation of S. Then the inverse of f is a permu tation of S. Proof. Well-known. D Lemma 5.3. Let S be a set. The set of all permutations, under the operation of composition of permutations, forms a group A(S). Proof. (5.2) implies that the set of permutations is closed under com position of functions. We check the three axioms for a group. We already proved that composition of functions is associative. Let i: S −! S be the identity function from S to S. Let f be a permutation of S. Clearly f ◦ i = i ◦ f = f. Thus i acts as an identity. Let f be a permutation of S. Then the inverse g of f is a permutation of S by (5.2) and f ◦ g = g ◦ f = i, by definition. Thus inverses exist and G is a group. D Lemma 5.4. Let S be a finite set with n elements. Then A(S) has n! elements. Proof. Well-known. D Definition 5.5. The group Sn is the set of permutations of the first n natural numbers. We want a convenient way to represent an element of Sn. The first way, is to write an element σ of Sn as a matrix. -

Permutation Group and Determinants (Dated: September 16, 2021)

Permutation group and determinants (Dated: September 16, 2021) 1 I. SYMMETRIES OF MANY-PARTICLE FUNCTIONS Since electrons are fermions, the electronic wave functions have to be antisymmetric. This chapter will show how to achieve this goal. The notion of antisymmetry is related to permutations of electrons’ coordinates. Therefore we will start with the discussion of the permutation group and then introduce the permutation-group-based definition of determinant, the zeroth-order approximation to the wave function in theory of many fermions. This definition, in contrast to that based on the Laplace expansion, relates clearly to properties of fermionic wave functions. The determinant gives an N-particle wave function built from a set of N one-particle waves functions and is called Slater’s determinant. II. PERMUTATION (SYMMETRIC) GROUP Definition of permutation group: The permutation group, known also under the name of symmetric group, is the group of all operations on a set of N distinct objects that order the objects in all possible ways. The group is denoted as SN (we will show that this is a group below). We will call these operations permutations and denote them by symbols σi. For a set consisting of numbers 1, 2, :::, N, the permutation σi orders these numbers in such a way that k is at jth position. Often a better way of looking at permutations is to say that permutations are all mappings of the set 1, 2, :::, N onto itself: σi(k) = j, where j has to go over all elements. Number of permutations: The number of permutations is N! Indeed, we can first place each object at positions 1, so there are N possible placements. -

Inclusion‒Exclusion Principle

Inclusionexclusion principle 1 Inclusion–exclusion principle In combinatorics, the inclusion–exclusion principle (also known as the sieve principle) is an equation relating the sizes of two sets and their union. It states that if A and B are two (finite) sets, then The meaning of the statement is that the number of elements in the union of the two sets is the sum of the elements in each set, respectively, minus the number of elements that are in both. Similarly, for three sets A, B and C, This can be seen by counting how many times each region in the figure to the right is included in the right hand side. More generally, for finite sets A , ..., A , one has the identity 1 n This can be compactly written as The name comes from the idea that the principle is based on over-generous inclusion, followed by compensating exclusion. When n > 2 the exclusion of the pairwise intersections is (possibly) too severe, and the correct formula is as shown with alternating signs. This formula is attributed to Abraham de Moivre; it is sometimes also named for Daniel da Silva, Joseph Sylvester or Henri Poincaré. Inclusion–exclusion illustrated for three sets For the case of three sets A, B, C the inclusion–exclusion principle is illustrated in the graphic on the right. Proof Let A denote the union of the sets A , ..., A . To prove the 1 n Each term of the inclusion-exclusion formula inclusion–exclusion principle in general, we first have to verify the gradually corrects the count until finally each identity portion of the Venn Diagram is counted exactly once. -

Multipermutations 1.1. Generating Functions

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector JOURNALOF COMBINATORIALTHEORY, Series A 67, 44-71 (1994) The r- Multipermutations SEUNGKYUNG PARK Department of Mathematics, Yonsei University, Seoul 120-749, Korea Communicated by Gian-Carlo Rota Received October 1, 1992 In this paper we study permutations of the multiset {lr, 2r,...,nr}, which generalizes Gesse| and Stanley's work (J. Combin. Theory Ser. A 24 (1978), 24-33) on certain permutations on the multiset {12, 22..... n2}. Various formulas counting the permutations by inversions, descents, left-right minima, and major index are derived. © 1994 AcademicPress, Inc. 1. THE r-MULTIPERMUTATIONS 1.1. Generating Functions A multiset is defined as an ordered pair (S, f) where S is a set and f is a function from S to the set of nonnegative integers. If S = {ml ..... mr}, we write {m f(mD, .... m f(mr)r } for (S, f). Intuitively, a multiset is a set with possibly repeated elements. Let us begin by considering permutations of multisets (S, f), which are words in which each letter belongs to the set S and for each m e S the total number of appearances of m in the word is f(m). Thus 1223231 is a permutation of the multiset {12, 2 3, 32}. In this paper we consider a special set of permutations of the multiset [n](r) = {1 r, ..., nr}, which is defined as follows. DEFINITION 1.1. An r-multipermutation of the set {ml ..... ran} is a permutation al ""am of the multiset {m~ .... -

Basic Operations for Fuzzy Multisets

Basic operations for fuzzy multisets A. Riesgoa, P. Alonsoa, I. D´ıazb, S. Montesc aDepartment of Mathematics, University of Oviedo, Spain bDepartment of Informatics, University of Oviedo, Spain cDepartment of Statistics and O.R., University of Oviedo, Spain Abstract In their original and ordinary formulation, fuzzy sets associate each element in a reference set with one number, the membership value, in the real unit interval [0; 1]. Among the various existing generalisations of the concept, we find fuzzy multisets. In this case, membership values are multisets in [0; 1] rather than single values. Mathematically, they can be also seen as a generalisation of the hesitant fuzzy sets, but in this general environment, the information about repetition is not lost, so that, the opinions given by the experts are better managed. Thus, we focus our study on fuzzy multisets and their basic operations: complement, union and intersection. Moreover, we show how the hesitant operations can be worked out from an extension of the fuzzy multiset operations and investigate the important role that the concepts of order and sorting sequences play in the basic difference between these two related approaches. Keywords: Fuzzy multiset; Hesitant fuzzy set; Complement; Aggregate union; Aggregate intersection. 1. Introduction The concept of a fuzzy set was originally introduced by Lotfi A. Zadeh as an extension of classical set theory [15]. Fuzzy sets aim to account for real-life situations where there is either limited knowledge or some sort of implicit ambiguity about whether an element should be considered a member of a set. This extension from the classical (or crisp) sets to the fuzzy ones is accomplished by replacing the Boolean characteristic function of a set, which maps each element of the universal set to either 0 (non-member) or 1 (member), with a more sophisticated membership function that maps elements into the real interval [0; 1]. -

Finding Direct Partition Bijections by Two-Directional Rewriting Techniques

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Discrete Mathematics 285 (2004) 151–166 www.elsevier.com/locate/disc Finding direct partition bijections by two-directional rewriting techniques Max Kanovich Department of Computer and Information Science, University of Pennsylvania, 3330 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA Received 7 May 2003; received in revised form 27 October 2003; accepted 21 January 2004 Abstract One basic activity in combinatorics is to establish combinatorial identities by so-called ‘bijective proofs,’ which consists in constructing explicit bijections between two types of the combinatorial objects under consideration. We show how such bijective proofs can be established in a systematic way from the ‘lattice properties’ of partition ideals, and how the desired bijections are computed by means of multiset rewriting, for a variety of combinatorial problems involving partitions. In particular, we fully characterizes all equinumerous partition ideals with ‘disjointly supported’ complements. This geometrical characterization is proved to automatically provide the desired bijection between partition ideals but in terms of the minimal elements of the order ÿlters, their complements. As a corollary, a new transparent proof, the ‘bijective’ one, is given for all equinumerous classes of the partition ideals of order 1 from the classical book “The Theory of Partitions” by G.Andrews. Establishing the required bijections involves two-directional reductions technique novel in the sense that forward and backward application of rewrite rules heads, respectively, for two di?erent normal forms (representing the two combinatorial types). It is well-known that non-overlapping multiset rules are con@uent. -

The Mathematics Major's Handbook

The Mathematics Major’s Handbook (updated Spring 2016) Mathematics Faculty and Their Areas of Expertise Jennifer Bowen Abstract Algebra, Nonassociative Rings and Algebras, Jordan Algebras James Hartman Linear Algebra, Magic Matrices, Involutions, (on leave) Statistics, Operator Theory Robert Kelvey Combinatorial and Geometric Group Theory Matthew Moynihan Abstract Algebra, Combinatorics, Permutation Enumeration R. Drew Pasteur Differential Equations, Mathematics in Biology/Medicine, Sports Data Analysis Pamela Pierce Real Analysis, Functions of Generalized Bounded Variation, Convergence of Fourier Series, Undergraduate Mathematics Education, Preparation of Pre-service Teachers John Ramsay Topology, Algebraic Topology, Operations Research OndˇrejZindulka Real Analysis, Fractal geometry, Geometric Measure Theory, Set Theory 1 2 Contents 1 Mission Statement and Learning Goals 5 1.1 Mathematics Department Mission Statement . 5 1.2 Learning Goals for the Mathematics Major . 5 2 Curriculum 8 3 Requirements for the Major 9 3.1 Recommended Timeline for the Mathematics Major . 10 3.2 Requirements for the Double Major . 10 3.3 Requirements for Teaching Licensure in Mathematics . 11 3.4 Requirements for the Minor . 11 4 Off-Campus Study in Mathematics 12 5 Senior Independent Study 13 5.1 Mathematics I.S. Student/Advisor Guidelines . 13 5.2 Project Topics . 13 5.3 Project Submissions . 14 5.3.1 Project Proposal . 14 5.3.2 Project Research . 14 5.3.3 Annotated Bibliography . 14 5.3.4 Thesis Outline . 15 5.3.5 Completed Chapters . 15 5.3.6 Digitial I.S. Document . 15 5.3.7 Poster . 15 5.3.8 Document Submission and oral presentation schedule . 15 6 Independent Study Assessment Guide 21 7 Further Learning Opportunities 23 7.1 At Wooster . -

Symmetric Relations and Cardinality-Bounded Multisets in Database Systems

Symmetric Relations and Cardinality-Bounded Multisets in Database Systems Kenneth A. Ross Julia Stoyanovich Columbia University¤ [email protected], [email protected] Abstract 1 Introduction A relation R is symmetric in its ¯rst two attributes if R(x ; x ; : : : ; x ) holds if and only if R(x ; x ; : : : ; x ) In a binary symmetric relationship, A is re- 1 2 n 2 1 n holds. We call R(x ; x ; : : : ; x ) the symmetric com- lated to B if and only if B is related to A. 2 1 n plement of R(x ; x ; : : : ; x ). Symmetric relations Symmetric relationships between k participat- 1 2 n come up naturally in several contexts when the real- ing entities can be represented as multisets world relationship being modeled is itself symmetric. of cardinality k. Cardinality-bounded mul- tisets are natural in several real-world appli- Example 1.1 In a law-enforcement database record- cations. Conventional representations in re- ing meetings between pairs of individuals under inves- lational databases su®er from several consis- tigation, the \meets" relationship is symmetric. 2 tency and performance problems. We argue that the database system itself should pro- Example 1.2 Consider a database of web pages. The vide native support for cardinality-bounded relationship \X is linked to Y " (by either a forward or multisets. We provide techniques to be im- backward link) between pairs of web pages is symmet- plemented by the database engine that avoid ric. This relationship is neither reflexive nor antire- the drawbacks, and allow a schema designer to flexive, i.e., \X is linked to X" is neither universally simply declare a table to be symmetric in cer- true nor universally false. -

Universal Invariant and Equivariant Graph Neural Networks

Universal Invariant and Equivariant Graph Neural Networks Nicolas Keriven Gabriel Peyré École Normale Supérieure CNRS and École Normale Supérieure Paris, France Paris, France [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Graph Neural Networks (GNN) come in many flavors, but should always be either invariant (permutation of the nodes of the input graph does not affect the output) or equivariant (permutation of the input permutes the output). In this paper, we consider a specific class of invariant and equivariant networks, for which we prove new universality theorems. More precisely, we consider networks with a single hidden layer, obtained by summing channels formed by applying an equivariant linear operator, a pointwise non-linearity, and either an invariant or equivariant linear output layer. Recently, Maron et al. (2019b) showed that by allowing higher- order tensorization inside the network, universal invariant GNNs can be obtained. As a first contribution, we propose an alternative proof of this result, which relies on the Stone-Weierstrass theorem for algebra of real-valued functions. Our main contribution is then an extension of this result to the equivariant case, which appears in many practical applications but has been less studied from a theoretical point of view. The proof relies on a new generalized Stone-Weierstrass theorem for algebra of equivariant functions, which is of independent interest. Additionally, unlike many previous works that consider a fixed number of nodes, our results show that a GNN defined by a single set of parameters can approximate uniformly well a function defined on graphs of varying size. 1 Introduction Designing Neural Networks (NN) to exhibit some invariance or equivariance to group operations is a central problem in machine learning (Shawe-Taylor, 1993).