The Weathervane George Mortimer Fire!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PH 'Wessex White Horses'

Notes from a Preceptor’s Handbook A Preceptor: (OED) 1440 A.D. from Latin praeceptor one who instructs, a teacher, a tutor, a mentor “A horse, a horse and they are all white” Provincial Grand Lodge of Wiltshire Provincial W Bro Michael Lee PAGDC 2017 The White Horses of Wessex Editors note: Whilst not a Masonic topic, I fell Michael Lee’s original work on the mysterious and mystical White Horses of Wiltshire (and the surrounding area) warranted publication, and rightly deserved its place in the Preceptors Handbook. I trust, after reading this short piece, you will wholeheartedly agree. Origins It seems a perfectly fair question to ask just why the Wiltshire Provincial Grand Lodge and Grand Chapter decided to select a white horse rather than say the bustard or cathedral spire or even Stonehenge as the most suitable symbol for the Wiltshire Provincial banner. Most continents, most societies can provide examples of the strange, the mysterious, that have teased and perplexed countless generations. One might include, for example, stone circles, ancient dolmens and burial chambers, ley lines, flying saucers and - today - crop circles. There is however one small area of the world that has been (and continues to be) a natural focal point for all of these examples on an almost extravagant scale. This is the region in the south west of the British Isles known as Wessex. To our list of curiosities we can add yet one more category dating from Neolithic times: those large and mysterious figures dominating our hillsides, carved in the chalk and often stretching in length or height to several hundred feet. -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

The Geoglyphs of Har Karkom (Negev, Israel): Classification and Interpretation

PAPERS XXIV Valcamonica Symposium 2011 THE GEOGLYPHS OF HAR KARKOM (NEGEV, ISRAEL): CLASSIFICATION AND INTERPRETATION Federico Mailland* Abstract - The geoglyphs of Har Karkom (Negev, Israel): classification and interpretation There is a debate on the possible interpretation of geoglyphs as a form of art, less durable than rock engravings, picture or sculpture. Also, there is a debate on how to date the geoglyphs, though some methods have been proposed. Har Karkom is a rocky mountain, a mesa in the middle of what today is a desert, a holy mountain which was worshipped in the prehis- tory. The flat conformation of the plateau and the fact that it was forbidden to the peoples during several millennia allowed the preservation of several geoglyphs on its flat ground. The geoglyphs of Har Karkom are drawings made on the surface by using pebbles or by cleaning certain areas of stones and other surface rough features. Some of the drawings are over 30 m long. The area of Har Karkom plateau and the southern Wadi Karkom was surveyed and zenithal pictures were taken by means of a balloon with a hanging digital camera. The aerial survey of Har Karkom plateau has reviewed the presence of about 25 geoglyph sites concentrated in a limited area of no more than 4 square km, which is considered to have been a sacred area at the time the geoglyphs were produced and defines one of the major world concentrations of this kind of art. The possible presence among the depictions of large mammals, such as elephant and rhino, already extinct in the area since late Pleistocene, may imply a Palaeolithic dating for some of the pebble drawings, which would make them the oldest pebble drawings known so far. -

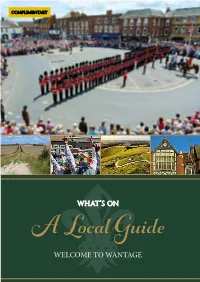

Welcome to Wantage

WELCOME TO WANTAGE Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com Welcome to Wantage in Oxfordshire. Our local guide is your essential tool to everything going on in the town and surrounding area. Wantage is a picturesque market town and civil parish in the Vale of White Horse and is ideally located within easy reach of Oxford, Swindon, Newbury and Reading – all of which are less than twenty miles away. The town benefits from a wealth of shops and services, including restaurants, cafés, pubs, leisure facilities and open spaces. Wantage’s links with its past are very strong – King Alfred the Great was born in the town, and there are literary connections to Sir John Betjeman and Thomas Hardy. The historic market town is the gateway to the Ridgeway – an ancient route through downland, secluded valleys and woodland – where you can enjoy magnificent views of the Vale of White Horse, observe its prehistoric hill figure and pass through countless quintessential English country villages. If you are already local to Wantage, we hope you will discover something new. KING ALFRED THE GREAT, BORN IN WANTAGE, 849AD Photographs on pages 1 & 11 kindly supplied by Howard Hill Buscot Park House photographs supplied by Buscot Park House For more information on Wantage, please see the “Welcome to Wantage” website www.wantage.com 3 WANTAGE THE NUMBER ONE LOCATION FOR SENIOR LIVING IN WANTAGE Fleur-de-Lis Wantage comprises 32 beautifully appointed one and two bedroom luxury apartments, some with en-suites. -

Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation

Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation The Mari Lwyd and the Horse Queen: Palimpsests of Ancient ideas A dissertation submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Celtic Studies 2012 Lyle Tompsen 1 Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation Abstract The idea of a horse as a deity of the land, sovereignty and fertility can be seen in many cultures with Indo-European roots. The earliest and most complete reference to this deity can be seen in Vedic texts from 1500 BCE. Documentary evidence in rock art, and sixth century BCE Tartessian inscriptions demonstrate that the ancient Celtic world saw this deity of the land as a Horse Queen that ruled the land and granted fertility. Evidence suggests that she could grant sovereignty rights to humans by uniting with them (literally or symbolically), through ingestion, or intercourse. The Horse Queen is represented, or alluded to in such divergent areas as Bronze Age English hill figures, Celtic coinage, Roman horse deities, mediaeval and modern Celtic masked traditions. Even modern Welsh traditions, such as the Mari Lwyd, infer her existence and confirm the value of her symbolism in the modern world. 2 Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation Table of Contents List of definitions: ............................................................................................................ 8 Introduction .................................................................................................................. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

Uffington and Baulking Neighbourhood Plan Website.10

Uffington and Baulking Neighbourhood Plan 2011-2031 Uffington Parish Council & Baulking Parish Meeting Made Version July 2019 Acknowledgements Uffington Parish Council and Baulking Parish Meeting would like to thank all those who contributed to the creation of this Plan, especially those residents whose bouquets and brickbats have helped the Steering Group formulate the Plan and its policies. In particular the following have made significant contributions: Gillian Butler, Wendy Davies, Hilary Deakin, Ali Haxworth, John-Paul Roche, Neil Wells Funding Groundwork Vale of the White Horse District Council White Horse Show Trust Consultancy Support Bluestone Planning (general SME, Characterisation Study and Health Check) Chameleon (HNA) Lepus (LCS) External Agencies Oxfordshire County Council Vale of the White Horse District Council Natural England Historic England Sport England Uffington Primary School - Chair of Governors P Butt Planning representing Developer - Redcliffe Homes Ltd (Fawler Rd development) P Butt Planning representing Uffington Trading Estate Grassroots Planning representing Developer (Fernham Rd development) R Stewart representing some Uffington land owners Steering Group Members Catherine Aldridge, Ray Avenell, Anna Bendall, Rob Hart (Chairman), Simon Jenkins (Chairman Uffington Parish Council), Fenella Oberman, Mike Oldnall, David Owen-Smith (Chairman Baulking Parish Meeting), Anthony Parsons, Maxine Parsons, Clare Roberts, Tori Russ, Mike Thomas Copyright © Text Uffington Parish Council. Photos © Various Parish residents and Tom Brown’s School Museum. Other images as shown on individual image. Executive Summary This Neighbourhood Plan (the ‘Plan’) was prepared jointly for the Uffington Parish Council and Baulking Parish Meeting. Its key purpose is to define land-use policies for use by the Planning Authority during determination of planning applications and appeals within the designated area. -

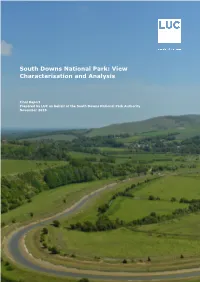

View Characterisation and Analysis

South Downs National Park: View Characterisation and Analysis Final Report Prepared by LUC on behalf of the South Downs National Park Authority November 2015 Project Title: 6298 SDNP View Characterisation and Analysis Client: South Downs National Park Authority Version Date Version Details Prepared by Checked by Approved by Director V1 12/8/15 Draft report R Knight, R R Knight K Ahern Swann V2 9/9/15 Final report R Knight, R R Knight K Ahern Swann V3 4/11/15 Minor changes to final R Knight, R R Knight K Ahern report Swann South Downs National Park: View Characterisation and Analysis Final Report Prepared by LUC on behalf of the South Downs National Park Authority November 2015 Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Registered in England Design 43 Chalton Street London Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Bristol Registered Office: Landscape Management NW1 1JD Glasgow 43 Chalton Street Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Edinburgh London NW1 1JD Mapping & Visualisation [email protected] FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper LUC BRISTOL 12th Floor Colston Tower Colston Street Bristol BS1 4XE T +44 (0)117 929 1997 [email protected] LUC GLASGOW 37 Otago Street Glasgow G12 8JJ T +44 (0)141 334 9595 [email protected] LUC EDINBURGH 28 Stafford Street Edinburgh EH3 7BD T +44 (0)131 202 1616 [email protected] Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background to the study 1 Aims and purpose 1 Outputs and uses 1 2 View patterns, representative views and visual sensitivity 4 Introduction 4 View -

Dartford, Kent

A Report on the Archaeological Excavations at Holy Trinity School, West Hill, Dartford, Kent This report has been downloaded from www.kentarchaeology.org.uk the website of the Kent Archaeological Society (Registered Charity 223382), Maidstone Museum and Bentlif Art Gallery, St Faith's St, Maidstone, Kent ME14 1LH, England. The copyright owner has placed the report on the site for download for personal or academic use. Any other use must be cleared with the copyright owner. Archaeology South-East Units 1 & 2, 2 Chapel Place Portslade, East Sussex BN41 1DR Tel: 01273 426830 Email: [email protected] www.archaeologyse.co.uk A REPORT ON THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS AT HOLY TRINITY SCHOOL, WEST HILL, DARTFORD, KENT Lucy Sibun with contributions by Luke Barber and David Dunkin INTRODUCTION Archaeology South-East (a division of the University College London Field Archaeology Unit) were commissioned by McCullochs plc to undertake an archaeological excavation at the site of the former Holy Trinity School, West Hill, Dartford. Planning permission for a residential development on the site had been granted by Dartford Borough Council in 1996. The site lies to the west of the modern and historic Roman and medieval centre of Dartford, on the south side of West Hill (Figure 1). The probable alignment of Roman Watling Street forms its northern boundary and the site of a medieval leper hospital is recorded to the east (SMR:TQ 57 SW 48). To the south is an outcrop of Boyn Gravel and a small number of Paleolithic handaxes have been found in the general area. According to the British Geological Survey 1:50,000 map the underlying geology is Head overlying Chalk. -

Kur Geriau? Vaikams Gali Būti Dar Sunkiau, Jeigu Atsi- Dalyvauja 15 Metų Paaugliai

Sek mūsų naujienas Facebook.com/Info Ekspresas SAVAITRAŠTIS TUVI IE ŠK L A S nemokamas L AI KRAŠTIS 2014 Nr. 10 lapkričio 13-19 FREE LITHUANIAN NEWSPAPER www.ekspresas.co.uk Didžioji Britanija Mokykla Lietuvoje LAPĖ apkandžiojo vaiką ar Anglijoje – kur 2 psl. geriau? Interviu 6-7psl. A.Kaniava - apie teatrą, muziką ir gyvenimą 10-11psl. Laisvalaikis Regent street kalėdinių lempučių įžiebimas 12 psl. www.ekspresas.co.uk Facebook.com/Info Ekspresas Kiekvieną savaitę patogiais autobusais bei mikro autobusais vežame keleivius maršrutais Anglija - Lietuva. Siuntinių pervežimas - nuo durų iki durų. LT: +370 60998811 www.lietuva-anglija-vezame.com Lapkričio mėn. bilietai UK: +44 7845 416024 į/iš Londoną (o) TIK £50 El.p.: [email protected] SAVAITRAŠTIS SAVAITRAŠTIS 2 2014 Nr. 10 lapkričio 13-19 Aktualijos: Didžioji Britanija Aktualijos: Didžioji Britanija 2014 Nr. 10 lapkričio 13-19 3 Parengė Karolina Germanavičiūtė Parengė Karolina Germanavičiūtė Įėjusi į namus lapė apkandžiojo vaiką Tariama, kad voro įkandimas Dvejų metų ber- riksmą. Mamai nubėgus į vaiko kambarį, niukas buvo išvežtas jie pamatė, kad vaiko koja kruvina, o kam- į ligoninę po to, kai bario kampe blaškosi lapė. lapė įėjusi į namus jį Sykį trenkusi gyvūnui, mama jo nesu- nusinešė moters gyvybę apkandžiojo. gavo ir lapė paspruko atgal pro ten iš kur 60-metė Pat Gough-Irwin (liet. Pet Gou- Pietų Londone, atėjusi. Irvin) po voro įkandimo mirė skausmuose New Addington (liet. Mažamečio tėvai su vaiku išskubėjo į ar- ir agonijoje. Prieš daugiau nei metus pas- Naujasis Adingtonas) timiausią „Croydon University“ ligoninę, klidus žiniai apie nuodingus vorus atsiras- gyvenanti šeima na- kur vaiko kulnas buvo sutvarstytas ir susiū- davo vis daugiau pranešimų apie šių vora- muose augina katiną, tas, bei buvo įduotas antibiotikų kursas. -

White Horse Hill Circular Walk

WHITE HORSE HILL CIRCULAR WALK 4¼ miles (6¾ km) – allow 2 hours (see map on final page) Introduction This circular walk within the North Wessex Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in Oxfordshire is 7 miles (11km) west of Wantage. It takes you through open, rolling downland, small pasture fields with some wonderful mixed hedgerows, woodland and a quintessential English village. It includes a classic section of The Ridgeway, with magnificent views of the Vale of White Horse to the north, and passes the unique site of White Horse Hill before descending the steep scarp slope to the small picturesque village of Woolstone in the Vale. The walk is waymarked with this ‘Ridgeway Circular Route’ waymark. Terrain and conditions • Tracks, field paths mostly through pasture and minor roads. • Quite strenuous with a steep downhill and uphill section. 174m (571 feet) ascent and descent. • There are 9 gates and one set of 5 steps, but no stiles. • Some paths can be muddy and slippery after rain. • There may be seasonal vegetation on the route. Preparation • Wear appropriate clothing and strong, comfortable footwear. • Carry water. • Take a mobile phone if you have one but bear in mind that coverage can be patchy in rural areas. • If you are walking alone it’s sensible, as a simple precaution, to let someone know where you are and when you expect to return. Getting there By Car: The walk starts in the National Trust car park for White Horse Hill (parking fee), south off the B4507 between Swindon and Wantage at map grid reference SU293866. -

Wiltshire White Horses (Pdf)

Wiltshire’s White Horses The Wiltshire Countryside is famous for its white horse chalk hill figures. It is thought that there have been 13 white horses in existence in Wiltshire, but only 8 are sll visible today. The oldest, largest and perhaps the most well known white horse is carved into the chalk hillside across the border in Oxfordshire. Lile is known of the history of the Uffington White Horse, but it is believed to have influenced the cung of the subsequent Wiltshire horses. The first of the Wiltshire white horses to appear was at Westbury in 878AD, although this figure is no longer visible as a new horse was cut on top in 1778. The most recent horse was cut on the hill above Devizes very near to Team Fredericks to celebrate the Millennium. Westbury: The original Westbury white horse was said to be very different in appearance to the horse that appears today. The earlier horse, if local sketches are to be believed, had short legs and a long heavy body, it wore a saddle and had a tail that pointed upwards. In 1778, Lord Abingdon's steward, a Mr. George Gee took it upon himself to re‐design the Westbury horse and changed the appearance of the landscape for ever more. The old horse was completely lost under this new design, and many branded Gee a Barbarian and vandal. Cherhill: A unique aracon of the Cherhill horse was its eye. Measuring four feet in diameter, Aslop filled the eye with glass boles embedded into the turf face down.