Planting and Growing Chestnut Trees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Missionary Perspectives and Experiences of 19Th and Early 20Th Century Droughts

1 2 “Everything is scorched by the burning sun”: Missionary perspectives and 3 experiences of 19th and early 20th century droughts in semi-arid central 4 Namibia 5 6 Stefan Grab1, Tizian Zumthurm,2,3 7 8 1 School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the 9 Witwatersrand, South Africa 10 2 Institute of the History of Medicine, University of Bern, Switzerland 11 3 Centre for African Studies, University of Basel, Switzerland 12 13 Correspondence to: Stefan Grab ([email protected]) 14 15 Abstract. Limited research has focussed on historical droughts during the pre-instrumental 16 weather-recording period in semi-arid to arid human-inhabited environments. Here we describe 17 the unique nature of droughts over semi-arid central Namibia (southern Africa) between 1850 18 and 1920. More particularly, our intention is to establish temporal shifts of influence and 19 impact that historical droughts had on society and the environment during this period. This is 20 achieved through scrutinizing documentary records sourced from a variety of archives and 21 libraries. The primary source of information comes from missionary diaries, letters and reports. 22 These missionaries were based at a variety of stations across the central Namibian region and 23 thus collectively provide insight to sub-regional (or site specific) differences in hydro- 24 meteorological conditions, and drought impacts and responses. Earliest instrumental rainfall 25 records (1891-1913) from several missionary stations or settlements are used to quantify hydro- 26 meteorological conditions and compare with documentary sources. The work demonstrates 27 strong-sub-regional contrasts in drought conditions during some given drought events and the 28 dire implications of failed rain seasons, the consequences of which lasted many months to 29 several years. -

Chestnut Growers' Guide to Site Selection and Environmental Stress

This idyllic orchard has benefited from good soil and irrigation. Photo by Tom Saielli Chestnut Growers’ Guide to Site Selection and Environmental Stress By Elsa Youngsteadt American chestnuts are tough, efficient trees that can reward their growers with several feet of growth per year. They’ll survive and even thrive under a range of conditions, but there are a few deal breakers that guarantee sickly, slow-growing trees. This guide, intended for backyard and small-orchard growers, will help you avoid these fatal mistakes and choose planting sites that will support strong, healthy trees. You’ll know you’ve done well when your chestnuts are still thriving a few years after planting. By then, they’ll be strong enough to withstand many stresses, from drought to a caterpillar outbreak, with much less human help. Soil Soil type is the absolute, number-one consideration when deciding where—or whether—to plant American chestnuts. These trees demand well-drained, acidic soil with a sandy to loamy texture. Permanently wet, basic, or clay soils are out of the question. So spend some time getting to know your dirt before launching a chestnut project. Dig it up, roll it between your fingers, and send in a sample for a soil test. Free tests are available through most state extension programs, and anyone can send a sample to the Penn State Agricultural Analytical Services Lab (which TACF uses) for a small fee. More information can be found at http://agsci.psu.edu/aasl/soil-testing. There are several key factors to look for. The two-foot-long taproot on this four- Acidity year-old root system could not have The ideal pH for American chestnut is 5.5, with an acceptable range developed in shallow soils, suggesting from about 4.5 to 6.5. -

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

Sample Planting Grids All Chestnuts in the Planting Must Have Permanent Embossed Numerical Tags for That Planting and Will Be Monitored by That Tag

Sample planting grids All chestnuts in the planting must have permanent embossed numerical tags for that planting and will be monitored by that tag. The basic module is 6 x 6 ft spacing with a minimum of 20 ft borders. Such plantings allow easy fencing and mowing. Rows and columns need not be continuous nor do they need to be the same length. Mapping should show gaps. Create a simple schematic map of the planting once done. These configurations can be modified in a wide variety of ways but if lengthened in either direction, a depth of a least 3 rows in any dimension should be maintained. Remember that the pines are an early succession planting designed to create early site coverage and encourage upward growth in hardwoods. Their removal will be a first step in thinning. Different configurations will impose other thinning regimens over time: for example, red oaks might be removed in #1 over time if there is high chestnut survival and vigorous growth. These plantings are designed to introduce at least 30 chestnuts on the site. These should represent at least 2‐3 chestnut families, and may include Kentucky stump sprout families. #1. Alternate row planting 024 ft 30 ft 36 ft 42 ft 48 ft 54 ft 60 ft 66 ft 72 ft 78 ft 98 ft Dimensions 24 ft Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Red Oak 110 x 98 ft 10780 sq ft 30 ft Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Chestnut 36 ft Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Red Oak Acreage 42 ft Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut Pine Red Oak Pine Chestnut -

How Climate Change Scorched the Nation in 2012

HOW CLIMATE CHANGE SCORCHED THE NATION IN 2012 NatioNal Wildlife federatioN i. Intro- ductioN Photo: Flickr/woodleywonderworks is climate change ruining our summers? It is certainly altering them in dramatic ways, and rarely for the better. The summer of 2012 has been full of extreme weather events connected to climate change. Heat records have been broken across the country, drought conditions forced the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to make the largest disaster declaration in U.S. history, and wildfires have raged throughout the West. New research by world-renowned climate scientist James Hansen con- firms that the increasingly common extreme weather events across the country, like record heat waves and drought, are linked to climate change.1 This report examines those climate change impacts whose harm is acutely felt in the summer. Heat waves; warming rivers, lakes, and streams; floods; drought; wildfires; and insect and pest infestations are problems we are dealing with this summer and what we are likely to face in future summers. As of August 23rd, 7 MILLION 2/3 of the country has experienced drought this acres of wildlife habitat and communities summer, much of it labeled “severe” 4 have burned in wildfires2 40 20 60 More than July’s average0 continental U.S. temperature 80 -20 113 MILLION 77.6°F100 people in the U.S. were in areas under 3.3°F above-40 the 20th-century average. 3 5 extreme heat advisories as of June 29 This was the-60 warmest month120 on record 0F NatioNal Wildlife federatioN Unfortunately, hot summers like this will occur much more frequently in years ahead. -

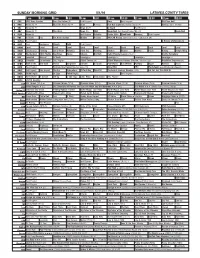

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Effects of a Prescribed Fire on Oak Woodland Stand Structure1

Effects of a Prescribed Fire on Oak Woodland Stand Structure1 Danny L. Fry2 Abstract Fire damage and tree characteristics of mixed deciduous oak woodlands were recorded after a prescription burn in the summer of 1999 on Mt. Hamilton Range, Santa Clara County, California. Trees were tagged and monitored to determine the effects of fire intensity on damage, recovery and survivorship. Fire-caused mortality was low; 2-year post-burn survey indicates that only three oaks have died from the low intensity ground fire. Using ANOVA, there was an overall significant difference for percent tree crown scorched and bole char height between plots, but not between tree-size classes. Using logistic regression, tree diameter and aspect predicted crown resprouting. Crown damage was also a significant predictor of resprouting with the likelihood increasing with percent scorched. Both valley and blue oaks produced crown resprouts on trees with 100 percent of their crown scorched. Although overall tree damage was low, crown resprouts developed on 80 percent of the trees and were found as shortly as two weeks after the fire. Stand structural characteristics have not been altered substantially by the event. Long term monitoring of fire effects will provide information on what changes fire causes to stand structure, its possible usefulness as a management tool, and how it should be applied to the landscape to achieve management objectives. Introduction Numerous studies have focused on the effects of human land use practices on oak woodland stand structure and regeneration. Studies examining stand structure in oak woodlands have shown either persistence or strong recruitment following fire (McClaran and Bartolome 1989, Mensing 1992). -

Chestnut Oak Botanical/Latin Name Quercus Montana

Chestnut Oak Botanical/Latin name Quercus Montana Chestnut Oak owes its name to its leaves, 4”-6” long, looking like those of the American Chestnut. It is a species of oak in the white oak group native to eastern U.S. Predominantly a ridge-top tree in hardwood forests. Also called Mountain Oak or Rock Oak because it grows in dry rocky habitats, sometimes even around large rocks. As a consequence of its dry habitat and harsh ridge-top exposure, it is not usually large, 59’–72’ tall; specimens growing in better conditions however can become large, up to 141’. It is a long-lived tree, with high-quality timber when well-formed. The heavy, durable, close-grained wood is used for fence posts, fuel, railroad ties and tannin. Saplings are easier to transplant than many other oaks because the taproot of the seedling disintegrates as the tree grows, and the remaining roots form a dense mat about three feet deep. It is monoecious, having pollen-bearing catkins in mid-spring that fertilize the inconspicuous female flowers on the same tree. It reproduces from seed as well as stump sprouts. The 1”-1-1/2” long acorns mature in one growing season, are among the largest of native American oaks and are a valuable wildlife food. Acorns are produced when a tree grown from seed is about 20 years of age, but sprouts from cut stumps can produce acorns in as little as three years after cutting. Extensive confusion between the chestnut oak (Q. montana) and the swamp chestnut oak (Quercus michauxii) has historically occurred. -

Impact of Structural Defects on the Surface Quality of Hardwood Species Sliced Veneers

applied sciences Article Impact of Structural Defects on the Surface Quality of Hardwood Species Sliced Veneers Vasiliki Kamperidou 1,* , Efstratios Aidinidis 2 and Ioannis Barboutis 1 1 Department of Harvesting and Technology of Forest Products, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 541 24 Thessaloniki, Greece; [email protected] 2 Department of Forestry and Natural Environment Management, Agricultural University of Athens, 118 55 Athens, Greece; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2310998895 Received: 20 August 2020; Accepted: 7 September 2020; Published: 9 September 2020 Abstract: The surface roughness constitutes one of the most critical properties of wood and wood veneers for their extended utilization, affecting the bonding ability of the veneers with one another in the manufacturing of wood composites, the finishing, coating and preservation processes, and the appearance and texture of the material surface. In this research work, logs of five significant European hardwood species (oak, chestnut, ash, poplar, cherry) of Balkan origin were sliced into decorative veneers. Their surface roughness was examined by applying a stylus tracing method, on typical wood structure areas of each wood species, as well as around the areas of wood defects (knots, decay, annual rings irregularities, etc.), to compare them and assess the impact of the defects on the surface quality of veneers. The chestnut veneers presented the smoothest surfaces, while ash veneers, despite the higher density, recorded the highest roughness. In most of the cases, the roughness was found to be significantly lower around the defects, compared to the typical structure surfaces, probably due to lower porosity, higher density and the presence of tensile wood. -

American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast

American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast Ohio A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Nathan A. Daniel June 2012 © 2012 Nathan A. Daniel. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast Ohio by NATHAN A. DANIEL has been approved for the Program of Environmental Studies and the College of Arts and Sciences by James M. Dyer Professor of Geography Brian C. McCarthy Professor of Environmental and Plant Biology Howard Dewald Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT DANIEL NATHAN A., M.S., June 2012, Environmental Studies American Chestnut Restoration in Eastern Hemlock-Dominated Forests of Southeast Ohio (51 pp.) Directors of Thesis: James M. Dyer and Brian C. McCarthy Restoration of American chestnut (Castanea dentata (Marsh.) Borkh.) is currently underway in eastern North American forests. American chestnut and eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis (L.) Carr.) trees historically co-occurred in these forests. Today, hemlock-dominated forests are in decline due to hemlock wooly adelgid (Adelges tsugae Annand) infestation, and as such, may serve as appropriate habitat for chestnut reestablishment. To investigate this notion, I evaluated the performance of American chestnut seedlings planted under healthy eastern hemlock-dominated canopies. Two process-oriented greenhouse experiments were also performed to study the response of American chestnut to drought stress and to test the competitive performance of chestnut against red maple (Acer rubrum (L.)), the most abundant hardwood found in the understory of regional hemlock-dominated forests. -

Chestnut Oak Forest/Woodland

Classification of the Natural Communities of Massachusetts Terrestrial Communities Descriptions Chestnut Oak Forest/Woodland Community Code: CT1A3A0000 State Rank: S4 Concept: Oak forest of dry ridgetops and upper slopes, dominated by chestnut oak with an often dense understory of scrub oak, heaths, or mountain laurel. Environmental Setting: Chestnut Oak Forests/Woodlands occur as long narrow bands along dry ridges and upper slopes with thin soil over acidic bedrock. They may extend down steep, convex, rocky, often west- or south-facing slopes where soil is shallow and dry. The canopy is closed to partially open (>25% cover). There tends to be deep oak leaf litter with slow decomposition. Often many trees have multiple fire scars and charred bases; fire appears to play a role in maintaining the community occurrences. Chestnut Oak Forests/Woodlands often occur in a mosaic with closed oak or pine - oak forests down slope and more open communities above. Vegetation Description: The canopy of Chestnut Oak Forests/Woodlands is dominated, often completely, by chestnut oak (Quercus montana). Less abundant associates include other oaks (black (Q. velutina), red (Q. rubra), and/or white (Q. alba), and less commonly, scarlet (Q. coccinea)), with red maple (Acer rubrum), and white or pitch pines (Pinus strobus, P. rigida). The subcanopy layer is sparse and consists of canopy species, black birch (Betula lenta), and sassafras (Sassafras albidum). Tall shrubs are lacking or the shrub layer may have scattered tree saplings, mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), striped maple (Acer pensylvanicum), American chestnut (Castanea dentata), and witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana). Short shrubs are dense in patches dominated by black huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata) and lowbush blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium and V. -

Restoration of the American Chestnut in New Jersey

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Restoration of the American Chestnut in New Jersey The American chestnut (Castanea dentata) is a tree native to New Jersey that once grew from Maine to Mississippi and as far west as Indiana and Tennessee. This tree with wide-spreading branches and a deep broad-rounded crown can live 500-800 years and reach a height of 100 feet and a diameter of more than 10 feet. Once estimated at 4 billion trees, the American chestnut Harvested chestnuts, early 1900's. has almost been extirpated in the last 100 years. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, New Jersey Field Value Office (Service) and its partners, including American Chestnut The American chestnut is valued Cooperators’ Foundation, American for its fruit and lumber. Chestnuts Chestnut Foundation, Monmouth are referred to as the “bread County Parks, Bayside State tree” because their nuts are Prison, Natural Lands Trust, and so high in starch that they can several volunteers, are working to American chestnut leaf (4"-8"). be milled into flour. Chestnuts recover the American chestnut in can be roasted, boiled, dried, or New Jersey. History candied. The nuts that fell to the ground were an important cash Chestnuts have a long history of crop for families in the northeast cultivation and use. The European U.S. and southern Appalachians chestnut (Castanea sativa) formed up until the twentieth century. the basis of a vital economy in Chestnuts were taken into towns the Mediterranean Basin during by wagonload and then shipped Roman times. More recently, by train to major markets in New areas in Southern Europe (such as York, Boston, and Philadelphia.