Taxonomic Names, Metadata, and the Semantic Web

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW COMBINATIONS in COURSETIA DNA Sequence

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE DNA Sequence Variation among Conspecific Accessions of the Legume Coursetia caribaea Reveals Geographically Localized Clades Here Ranked as Species AUTHORS Pennington, T; Lavin, M; Hughes, CE; et al. JOURNAL Systematic Botany DEPOSITED IN ORE 03 December 2018 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/34959 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Lavin et al. 1 LAVIN ET AL.: NEW COMBINATIONS IN COURSETIA DNA Sequence Variation among Conspecific Accessions of the Legume Coursetia caribaea Reveal Geographically Localized Clades Here Ranked as Species Matt Lavin,1,10 R. Toby Pennington,2 Colin E. Hughes,3 Gwilym P. Lewis,4 Alfonso Delgado-Salinas,5 Rodrigo Duno de Stefano,6 Luciano P. de Queiroz,7 Domingos Cardoso,8 and Martin F. Wojciechowski9 1Plant Sciences and Plant Pathology, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana 59717, USA. 2Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 20A Inverleith Row, Edinburgh, Scotland, EH3 5LR, UK. 3University of Zurich, Department of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Zollikerstrasse 107, 8008 Zurich, Switzerland. 4Comparative Plant and Fungal Biology Department, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3AB, UK. 5Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Biología, Departamento de Botánica, Apartado Postal 70- 233, 04510 Ciudad de México, México. 6Herbarium, Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A. C., Calle 43. No. 130, Col. Chuburná de Hidalgo, 97200 Mérida, Yucatán, México. -

Fruits and Seeds of Genera in the Subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae)

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume I December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume I Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Abstract Kirkbride, Joseph H., Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L radicle junction, Crotalarieae, cuticle, Cytiseae, Weitzman. 2003. Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Dalbergieae, Daleeae, dehiscence, DELTA, Desmodieae, Faboideae (Fabaceae). U. S. Department of Agriculture, Dipteryxeae, distribution, embryo, embryonic axis, en- Technical Bulletin No. 1890, 1,212 pp. docarp, endosperm, epicarp, epicotyl, Euchresteae, Fabeae, fracture line, follicle, funiculus, Galegeae, Genisteae, Technical identification of fruits and seeds of the economi- gynophore, halo, Hedysareae, hilar groove, hilar groove cally important legume plant family (Fabaceae or lips, hilum, Hypocalypteae, hypocotyl, indehiscent, Leguminosae) is often required of U.S. -

Root System Morphology of Fabaceae Species from Central Argentina

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Wulfenia Jahr/Year: 2003 Band/Volume: 10 Autor(en)/Author(s): Weberling Focko, Kraus Teresa Amalia, Bianco Cesar Augusto Artikel/Article: Root system morphology of Fabaceae species from central Argentina 61-72 © Landesmuseum für Kärnten; download www.landesmuseum.ktn.gv.at/wulfenia; www.biologiezentrum.at Wulfenia 10 (2003): 61–72 Mitteilungen des Kärntner Botanikzentrums Klagenfurt Root system morphology of Fabaceae species from central Argentina Teresa A. Kraus, César A. Bianco & Focko Weberling Summary: Root systems of different Fabaceae genera from central Argentina, are studied in relation to habitat conditions. Species of the following genera were analyzed: Adesmia, Acacia, Caesalpinia, Coursetia, Galactia, Geoffroea, Hoffmannseggia, Prosopis, Robinia, Senna, Stylosanthes and Zornia. Seeds of selected species were collected in each soil geographic unit and placed in glass recipients to analyze root system growth and branching degree during the first months after germination. Soil profiles that were already opened up were used to study subterranean systems of arboreal species. Transverse sections of roots were cut and histological tests were carried out to analyze reserve substances. All species studied show an allorhizous system, whose variants are related to soil profile characteristics. Roots with plagiotropic growth are observed in highland grass steppes (Senna birostris var. hookeriana and Senna subulata), and in soils containing calcium carbonate (Prosopis caldenia). Root buds are found in: Acacia caven, Caesalpinia gilliesii, Senna aphylla, Geoffroea decorticans, Robinia pseudo-acacia, Adesmia cordobensis and Hoffmannseggia glauca. Two variants are observed in transverse sections of roots: a) woody with predominance of xylematic area with highly lignified cells, and b) fleshy with predominance of parenchymatic tissue. -

Wojciechowski Quark

Wojciechowski, M.F. (2003). Reconstructing the phylogeny of legumes (Leguminosae): an early 21st century perspective In: B.B. Klitgaard and A. Bruneau (editors). Advances in Legume Systematics, part 10, Higher Level Systematics, pp. 5–35. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. RECONSTRUCTING THE PHYLOGENY OF LEGUMES (LEGUMINOSAE): AN EARLY 21ST CENTURY PERSPECTIVE MARTIN F. WOJCIECHOWSKI Department of Plant Biology, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona 85287 USA Abstract Elucidating the phylogenetic relationships of the legumes is essential for understanding the evolutionary history of events that underlie the origin and diversification of this family of ecologically and economically important flowering plants. In the ten years since the Third International Legume Conference (1992), the study of legume phylogeny using molecular data has advanced from a few tentative inferences based on relatively few, small datasets into an era of large, increasingly multiple gene analyses that provide greater resolution and confidence, as well as a few surprises. Reconstructing the phylogeny of the Leguminosae and its close relatives will further advance our knowledge of legume biology and facilitate comparative studies of plant structure and development, plant-animal interactions, plant-microbial symbiosis, and genome structure and dynamics. Phylogenetic relationships of Leguminosae — what has been accomplished since ILC-3? The Leguminosae (Fabaceae), with approximately 720 genera and more than 18,000 species worldwide (Lewis et al., in press) is the third largest family of flowering plants (Mabberley, 1997). Although greater in terms of the diversity of forms and number of habitats in which they reside, the family is second only perhaps to Poaceae (the grasses) in its agricultural and economic importance, and includes species used for foods, oils, fibre, fuel, timber, medicinals, numerous chemicals, cultivated horticultural varieties, and soil enrichment. -

A Flora of Southwestern Arizona

Felger, R.S. and S. Rutman. 2015. Ajo Peak to Tinajas Altas: a flora of southwestern Arizona. Part 14. Eudicots: Fabaceae – legume family. Phytoneuron 2015-58: 1–83. Published 20 Oct 2015. ISSN 2153 733X AJO PEAK TO TINAJAS ALTAS: A FLORA OF SOUTHWESTERN ARIZONA. PART 14. EUDICOTS: FABACEAE – LEGUME FAMILY RICHARD STEPHEN FELGER Herbarium, University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 & Sky Island Alliance P.O. Box 41165 Tucson, Arizona 85717 *Author for correspondence: [email protected] SUSAN RUTMAN 90 West 10th Street Ajo, Arizona 85321 [email protected] ABSTRACT A floristic account is provided for the legume family (Fabaceae) as part of the vascular plant flora of the contiguous protected areas of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, and the Tinajas Altas Region in the heart of the Sonoran Desert of southwestern Arizona. This flora includes 47 legume species in 28 genera, which is 6% of the total local vascular plant flora. These legumes are distributed across three subfamilies: Caesalpinioideae with 7 species, Mimosoideae 9 species, and Papilionoideae 28 species. Organ Pipe includes 38 legume species, Cabeza Prieta 22 species, and Tinajas Altas 10 species. Perennials, ranging from herbaceous to trees, account for 49 percent of the flora, the rest being annuals or facultative annuals or perennials and mostly growing during the cooler seasons. This publication, encompassing the legume family, is our fourteenth contribution to the vascular plant flora in southwestern Arizona. The flora area covers 5141 km2 (1985 mi2) in the Sonoran Desert (Figure 1). These contributions are published in Phytoneuron and also posted on the website of the University of Arizona Herbarium (http://cals.arizona.edu/herbarium/content/flora-sw- arizona). -

Previous Publications from Participants on Papilionoid Legumes

Previous publications from participants on papilionoid legumes Cai Z, Guisinger M, Kim H-G, Ruck E, Blazier JC, McMurtry V, Kuehl JV, Boore J, Jansen RK 2008. Extensive reorganization of the plastid genome of Trifolium subterraneum (Fabaceae) is associated with numerous repeated sequences and novel DNA insertions. J Mol Evol 67: 696–704. Cardoso, D., Lima, H. C. de, Rodrigues, R. S., Queiroz, L. P. de, Pennington, R. T., & Lavin, M. 2012a. The realignment of Acosmium sensu stricto with the Dalbergioid clade (Leguminosae: Papilionoideae) reveals a proneness for independent evolution of radial floral symmetry among early-branching papilionoid legumes. Taxon 61: 1057-1073. Cardoso, D., Lima, H. C. de, Rodrigues, R. S., Queiroz, L. P. de, Pennington, R. T., & Lavin, M. 2012b. The Bowdichia clade of genistoid legumes: Phylogenetic analysis of combined molecular and morphological data and a recircumscription of Diplotropis. Taxon 61: 1074-1087. Cardoso, D, Queiroz, L. P. de, Pennington, R. T., Lima, H.C. de, Fonty, E., Wojciechowski, M.F., & Lavin, M. 2012c. Revisiting the phylogeny of papilionoid legumes: new insights from comprehensively sampled early-branching lineages. Amer. J. Bot. 99: 1991-2013. Cardoso, D., Queiroz, L. P. de, Lima, H. C. de, Suganuma, E., van den Berg, C., & Lavin, M. 2013a. A molecular phylogeny of the vataireoid legumes underscores floral evolvability that is general to many early-branching papilionoid lineages. Amer. J. Bot. 100: 403-421. Cardoso D., Pennington, R. T., Queiroz L. P. de, Boatwright, J.S., van Wyk, B.-E., Wojciechowski, M. F., & Lavin, M. 2013b. Reconstructing the deep-branching relationships of the papilionoid legumes. -

The Contrasting Nature of Woody Plant Species in Different Neotropical Forest Biomes Reflects Differences in Ecological Stability

Review Tansley review The contrasting nature of woody plant species in different neotropical forest biomes reflects differences in ecological stability Author for correspondence: R. Toby Pennington1 and Matt Lavin2 R. Toby Pennington 1 2 Tel: +44 (0)131 248 2818 Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 20a Inverleith Row, Edinburgh, EH3 5LR, UK; Department of Plant Sciences & Plant Pathology, Email: [email protected] Montana State University, PO Box 173150, Bozeman, MT 59717-3150, USA Received: 28 May 2015 Accepted: 7 September 2015 Contents Summary 1 VI. Ages of species 8 I. Introduction 1 VII. Species from neotropical savannas 10 II. Neotropical biomes 2 VIII. Conclusions and ways forward 10 III. Coalescence 3 Acknowledgements 11 IV. Species from seasonally dry tropical forests (SDTFs) 3 References 11 V. Species from rain forest, with particular focus on Amazonia 4 Summary New Phytologist (2015) A fundamental premise of this review is that distinctive phylogenetic and biogeographic patterns doi: 10.1111/nph.13724 in clades endemic to different major biomes illuminate the evolutionary process. In seasonally dry tropical forests (SDTFs), phylogenies are geographically structured and multiple individuals Key words: Amazonia, dispersal, rain forest, representing single species coalesce. This pattern of monophyletic species, coupled with their old seasonally dry tropical forest, speciation, species stem ages, is indicative of maintenance of small effective population sizes over species. evolutionary timescales, which suggests that SDTF is difficult to immigrate into because of persistent resident lineages adapted to a stable, seasonally dry ecology. By contrast, lack of coalescence in conspecific accessions of abundant and often widespread species is more frequent in rain forests and is likely to reflect large effective population sizes maintained over huge areas by effective seed and pollen flow. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Edinburgh Research Explorer Edinburgh Research Explorer Dispersal assembly of rain forest tree communities across the Amazon basin Citation for published version: Dexter, K, Lavin, M, Torke, B, Twyford, A, Kursar, TA, Coley, PD, Drake, C, Hollands, R & Pennington, RT 2017, 'Dispersal assembly of rain forest tree communities across the Amazon basin' Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1613655114 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1073/pnas.1613655114 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 05. Apr. 2019 1 Classification: BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES 2 Title: Dispersal assembly of rain forest tree communities across the Amazon basin 3 Kyle G. Dexter1,2*, Matt Lavin3, Benjamin Torke4, Alex D. Twyford5, Thomas A. Kursar6, Phyllis D. 4 Coley6, Camila Drake2, Ruth Hollands2, R. Toby Pennington2* 5 *KGD and RTP contributed equally to this manuscript 6 7 1School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, 201 Crew Building, King’s Buildings, Edinburgh EH9 8 3FF, UK 9 2Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 20a Inverleith Row, Edinburgh EH3 5LR, UK 10 3Department of Plant Sciences & Plant Pathology, P.O. -

Microsoft Word

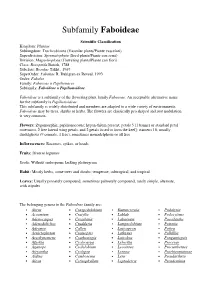

Subfamily Faboideae Scientific Classification Kingdom: Plantae Subkingdom: Tracheobionta (Vascular plants/Piante vascolari) Superdivision: Spermatophyta (Seed plants/Piante con semi) Division: Magnoliophyta (Flowering plants/Piante con fiori) Class: Rosopsida Batsch, 1788 Subclass: Rosidae Takht., 1967 SuperOrder: Fabanae R. Dahlgren ex Reveal, 1993 Order: Fabales Family: Fabaceae o Papilionacee Subfamily: Faboideae o Papilionoideae Faboideae is a subfamily of the flowering plant family Fabaceae . An acceptable alternative name for the subfamily is Papilionoideae . This subfamily is widely distributed and members are adapted to a wide variety of environments. Faboideae may be trees, shrubs or herbs. The flowers are classically pea shaped and root nodulation is very common. Flowers: Zygomorphic, papilionaceous; hypan-thium present; petals 5 [1 banner or standard petal outermost, 2 free lateral wing petals, and 2 petals fused to form the keel]; stamens 10, usually diadelphous (9 connate, 1 free), sometimes monadelphous or all free Inflorescences: Racemes, spikes, or heads Fruits: Diverse legumes Seeds: Without endosperm; lacking pleurogram Habit: Mostly herbs, some trees and shrubs; temperate, subtropical, and tropical Leaves: Usually pinnately compound, sometimes palmately compound, rarely simple, alternate, with stipules The belonging genera to the Faboideae family are: • Abrus • Craspedolobium • Kummerowia • Podalyria • Acosmium • Cratylia • Lablab • Podocytisus • Adenocarpus • Crotalaria • Laburnum • Poecilanthe • Adenodolichos • Cruddasia -

Studies on Foliar Venation Patterns in the Papilionoideae (Leguminosae) Hendrik Bernard Weyland Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1968 Studies on foliar venation patterns in the Papilionoideae (Leguminosae) Hendrik Bernard Weyland Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Weyland, Hendrik Bernard, "Studies on foliar venation patterns in the Papilionoideae (Leguminosae) " (1968). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 3705. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/3705 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfihned exactly as received 68-14 830 WEYLAND, Hendrik Bernard, 1930- STUDIES ON FOLIAR VENATION PATTERNS IN THE PAPILIONOIDEAE (LEGUMINOSAE). Iowa State University, Ph.D., 1968 Botany University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan STUDIES ON FOLIAR VENATION PATTERNS IN THE PAPILIONOIDEAE (LEGUMINOSAE) by Hendrik Bernard Weyland A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major Subject: Plant Morphology Approved : Signature was redacted for privacy. In Charge of Major Work Signature was redacted for privacy. Head of Major Department -

The Contrasting Nature of Woody Plant Species in Different Neotropical Forest Biomes Reflects Differences in Ecological Stability

Review Tansley review The contrasting nature of woody plant species in different neotropical forest biomes reflects differences in ecological stability Author for correspondence: R. Toby Pennington1 and Matt Lavin2 R. Toby Pennington 1 2 Tel: +44 (0)131 248 2818 Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 20a Inverleith Row, Edinburgh, EH3 5LR, UK; Department of Plant Sciences & Plant Pathology, Email: [email protected] Montana State University, PO Box 173150, Bozeman, MT 59717-3150, USA Received: 28 May 2015 Accepted: 7 September 2015 Contents Summary 25 VI. Ages of species 32 I. Introduction 25 VII. Species from neotropical savannas 33 II. Neotropical biomes 26 VIII. Conclusions and ways forward 34 III. Coalescence 27 Acknowledgements 35 IV. Species from seasonally dry tropical forests (SDTFs) 27 References 35 V. Species from rain forest, with particular focus on Amazonia 28 Summary New Phytologist (2016) 210: 25–37 A fundamental premise of this review is that distinctive phylogenetic and biogeographic patterns doi: 10.1111/nph.13724 in clades endemic to different major biomes illuminate the evolutionary process. In seasonally dry tropical forests (SDTFs), phylogenies are geographically structured and multiple individuals Key words: Amazonia, dispersal, rain forest, representing single species coalesce. This pattern of monophyletic species, coupled with their old seasonally dry tropical forest, speciation, species stem ages, is indicative of maintenance of small effective population sizes over species. evolutionary timescales, which suggests that SDTF is difficult to immigrate into because of persistent resident lineages adapted to a stable, seasonally dry ecology. By contrast, lack of coalescence in conspecific accessions of abundant and often widespread species is more frequent in rain forests and is likely to reflect large effective population sizes maintained over huge areas by effective seed and pollen flow. -

Universidade Estadual De Campinas Instituto De Biologia

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE BIOLOGIA EVERTON ALVES MACIEL LINKING PATTERNS AND PROCESSES IN TREE PLANT COMMUNITIES TO CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN SAVANNAS VINCULANDO PADRÕES E PROCESSOS EM COMUNIDADES ARBÓREAS AO PLANEJAMENTO E MANEJO DA CONSERVAÇÃO DE SAVANAS DA AMÉRICA DO SUL Campinas 2020 EVERTON ALVES MACIEL LINKING PATTERNS AND PROCESSES IN TREE PLANT COMMUNITIES TO CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE SOUTH AMERICAN SAVANNAS VINCULANDO PADRÕES E PROCESSOS EM COMUNIDADES ARBÓREAS AO PLANEJAMENTO E MANEJO DA CONSERVAÇÃO DE SAVANAS DA AMÉRICA DO SUL Thesis presented to the Institute of Biology of the University of Campinas in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Plant Biology. Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Biologia da Universidade Estadual de Campinas como parte dos requisitos exigidos para a obtenção do Título de Doutor em Biologia Vegetal. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fernando Roberto Martins ESTE ARQUIVO DIGITAL CORRESPONDE À VERSÃO FINAL DA TESE DEFENDIDA PELO ALUNO EVERTON ALVES MACIEL ORIENTADA PELO PROF. DR. FERNANDO ROBERTO MARTINS Campinas 2020 Ficha catalográfica Universidade Estadual de Campinas Biblioteca do Instituto de Biologia Mara Janaina de Oliveira - CRB 8/6972 Maciel, Everton Alves, 1982- M187L Linking patterns and processes in tree plant communities to conservation and management of the South American savannas / Everton Alves Maciel. – Campinas, SP : [s.n.], 2020. Orientador: Fernando Roberto Martins. Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Biologia. 1. Florestas - Conservação. 2. Ecologia das savanas. 3. Áreas protegidas. 4. Levantamento florístico. 5. Plantas raras. 6. Biomassa vegetal. I. Martins, Fernando Roberto, 1949-. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Biologia.