Whose Centary Public Art Project...Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Onobrakpeya & Workshop

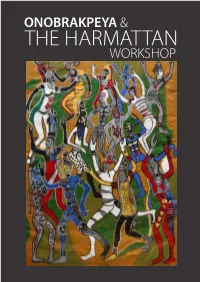

ONOBRAKPEYA & THE HARMATTAN WORKSHOP 78 Ezekiel Udubrae (detail) AGBARHA OTOR LANDSCAPE 2007 oil on canvas 122 x 141cm 78 Ezekiel Udubrae (detail) AGBARHA OTOR LANDSCAPE 2007 oil on canvas 122 x 141cm ONOBRAKPEYA & THE HARMATTAN WORKSHOP 1 Bruce Onobrakpeya OBARO ISHOSHI ROVUE ESIRI (THE FRONT OF THE CHURCH OF GOOD NEWS) plastocast 125 x 93 cm 3 ONOBRAKPEYA & THE HARMATTAN WORKSHOP 1 Bruce Onobrakpeya OBARO ISHOSHI ROVUE ESIRI (THE FRONT OF THE CHURCH OF GOOD NEWS) plastocast 125 x 93 cm 3 ONOBRAKPEYA & THE HARMATTAN WORKSHOP CURATED BY SANDRA MBANEFO OBIAGO at the LAGOS COURT OF ARBITRATION SEPT. 16 - DEC 16, 2016 240 Aderinsoye Aladegbongbe (detail) SHOWERS OF BLESSING 2009 acrylic on canvas 60.5 x 100cm 5 ONOBRAKPEYA & THE HARMATTAN WORKSHOP CURATED BY SANDRA MBANEFO OBIAGO at the LAGOS COURT OF ARBITRATION SEPT. 16 - DEC 16, 2016 240 Aderinsoye Aladegbongbe (detail) SHOWERS OF BLESSING 2009 acrylic on canvas 60.5 x 100cm 5 We wish to acknowledge the generous support of: Lead Sponsor Sponsors and Partners Contents Welcome by Yemi Candide Johnson 9 Foreword by Andrew Skipper 11 Preface by Prof. Bruce Onobrakpeya 13 Curatorial Foreword by Sandra Mbanefo Obiago 19 Bruce Onobrakpeya: Human Treasure 25 The Long Road to Agbarah-Otor 33 Credits Celebration by Sam Ovraiti 97 Editorial & Artistic Direction: Sandra Mbanefo Obiago Photography, Layout & Design: Adeyinka Akingbade Our Culture, Our Wealth 99 Exhibition Assistant Manager: Nneoma Ilogu Art at the Heart of Giving by Prof. Peju Layiwola 121 Harmattan Workshop Editorial: Bruce Onobrakpeya, Sam Ovraiti, Moses Unokwah Friendships & Connectivity 133 BOF Exhibition Team: Udeme Nyong, Bode Olaniran, Pius Emorhopkor, Ojo Olaniyi, Oluwole Orowole, Dele Oluseye, Azeez Alawode, Patrick Akpojotor, Monsuru Alashe, A Master & His Workshops by Tam Fiofori 149 Rasaki Adeniyi, Ikechukwu Ajibo and Daniel Ajibade. -

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

Arts Council of the African Studies Association Roundtables Seeking Participants

Arts Council of the African Studies Association Roundtables Seeking Participants ACASA members, please submit papers to roundtable chairs by January 16, 2017 17th Triennial Symposium on African Art University of Ghana, Legon Campus Institute of African Studies August 8-13, 2017 www.acasaonline.org ROUNDTABLE TITLE: Women and Contemporary Nigerian Art: reception, support, and patronage Contemporary art in Nigeria is fascinating due in no small part to women. This roundtable looks at the work and the history of Nigeria’s female artists. Collette Omogbai, Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu and Afie Ekong are pioneering firsts: each influenced Nigerian modernism. Omogbai was the first woman to receive an arts education; Ugbodaga-Ngu during the 1950s was the only Nigerian faculty member at Zaria’s Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology (NCAST), and, Ekong wielded considerable influence on the 1960s Lagos art scene. Today, Nike Okundaye, and Peju Alatise, are perhaps two of Nigeria’s best-known advocates for gender equity. Often working without the safety net of conventionality, each with laser focus, exposes particular problems within Nigeria. Through the use of Yoruba folklore, they have shown spotlights on forced marriage, misogyny, and, tradition. Eschewing the feminist label, both have boldly chosen their own path. They are the continuum of the work of Nigeria’s first women artists. Neither ascribe to western labels, instead they rewrite the ways in which the contemporary arts of Nigeria are to be received on the global stage. Both demand that the work is accepted for what it is rather from whence it hails. This roundtable shall look at the ways in which women impact Nigeria today through their art and advocacy. -

Bruce Onobrakpeya and the Harmattan Workshop Artistic Experimentation in the Niger Delta

Bruce Onobrakpeya and the Harmattan Workshop Artistic Experimentation in the Niger Delta Janet Stanley Bruce Onobrakpeya (b. August 30,1932) is unique A LIFETIME OF GIVING BACK among Nigerian artists, not only because he has The Bruce Onobrakpeya Foundation (BOF), established in had one of the longest, most productive art careers 1999, is now the parent organization of the Harmattan Work- in all of Nigeria,1 but also because he bridges the shop. It became the conduit for the Ford Foundation fund- divide between the academy and the workshop, a ing which was critical to the Harmattan project over the next divide that bedevils the Nigerian art discourse and decade.5 Onobrakpeya has made significant financial contribu- practice, going back to the competing Aina Onabolu-Kenneth tions to the project from his own pocket and his art sales.6 He Murray philosophies (Oloidi 1998:42)/ Innovation and experi- has also received support from a few Nigerian corporations (e.g., mentation are hallmarks of Onobrakpeya's career, which carry Nestle Nigeria, Cadbury Nigeria, and Nigerian Breweries) and over into the Harmattan Workshop that he founded in 1998 in has enjoyed the collaboration and support of the National Gal- his hometown of Agbarha-Otor in the Niger Delta. Trained as lery of Art, Arthouse, the Society of Nigerian Artists, Signature a painter, Onobrakpeya graduated from the art program at the Gallery, Terra Kulture, and Omooba Yemisi Adedoyin Shyllon Nigerian College of Art, Science, and Technology in Zaria in 1961 Art Foundation (OYASAF). Private individuals have also con- (Fig. 1). A few years later, he participated in some of the Mbari tributed money and in-kind gifts. -

MAGAZINE This Issue Features the College of Arts & Sciences SPRING 2018

DAKOTAFOR OUR ALUMNI, PARENTS AND FRIENDS STATEMAGAZINE This issue features the College of Arts & Sciences SPRING 2018 1 Dear DSU Community, This issue of our alumni magazine focuses on the arts and sciences at Dakota State University. Studies in these areas have always been and continue to be key contributors to the success of our DSU graduates. These days a lot of the conversation around getting a college education focuses on career-readiness and one of the core missions of DSU, digital fluency, or skills in the cyber sciences. A DSU degree leads in both. However, university graduates today more than ever will be living out their professional careers in a rapidly changing global economy of ever greater diversity and multidisciplinary interdependence. Research has shown that today’s graduates will average five to seven career changes in their lifetime. Whatever their chosen career, they will live through swiftly evolving modifications in the skills and knowledge required to continue to be successful in their fields. A recent survey revealed that 90 percent of all recent college graduates believed they were well prepared for their jobs. Unfortunately, only half of hiring managers agreed with them. Interestingly, the hiring managers were not concerned about their young employees’ knowledge of the field in which they had landed a job. No, the companies were most concerned about these graduates’ ability to problem solve, critical thinking skills, creativity, writing proficiency, attention to detail, and speaking ability. Those were the skills companies found most lacking in the new grads joining their efforts. While education in a specific field can contribute to these soft skills, it is study and participation more generally in the arts and sciences that zeroes in on them. -

Annual Repor Annual Report 2006

Annual Report 2006 COUNCIL FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH IN AFRICA © Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa 2006 Avenue Cheikh Anta Diop angle Canal IV BP 3304, Dakar, CP 18524 Senegal Tel. +221 825 98 22/825 98 23 +221 864 01 36-8 Fax +221 824 12 89 Email: [email protected] Website: www.codesria.org Type setting : Daouda Thiam Printed by Imprimerie Saint Paul, Dakar, Senegal The Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA) is an independent organisa- tion whose principal objectives are facilitating research, promoting research-based publishing and creating multiple forums geared towards the exchange of views and information among African researchers. It chal- lenges the fragmentation of research through the creation of thematic research networks that cut across linguis- tic and regional boundaries. CODESRIA publishes a quarterly journal, Africa Development, the longest standing Africa-based social science journal; Afrika Zamani, a journal of history; the African Sociological Review; African Journal of International Affairs (AJIA); Africa Review of Books; and the Journal of Higher Education in Africa. It copublishes the Africa Media Review and Identity, Culture and Politics: An Afro-Asian Dialogue. Research results and other activities of the institution are disseminated through ‘Working Papers’, ‘Monograph Series’, ‘CODESRIA Book Series’, and the CODESRIA Bulletin. CODESRIA would like to express its gratitude to the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA/SAREC), the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ford Foundation, MacArthur Founda- tion, Carnegie Corporation, NORAD, the Danish Agency for International Development (DANIDA), the French Ministry of Cooperation, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Rockefeller Foundation, FINIDA, CIDA, IIEP/ADEA, OECD, OXFAM America, UNICEF and the Government of Senegal for supporting its research, training and publication programmes. -

CFP: Seeking Roundtable Participants. Topic: Women and Contemporary Nigerian Art: Reception, Support, and Patronage

CFP: seeking roundtable participants. Topic: Women and Contemporary Nigerian Art: reception, support, and patronage. Convener: Francine Kola-Bankole, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, [email protected] 100-word Abstract: Collette Omogbai, Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu and Afie Ekong are pioneering firsts: Omogbai was the first woman to receive an arts education; Ugbodaga-Ngu during the 1950s was the only Nigerian faculty member at Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology (NCAST) in Zaria, and Ekong wielded considerable influence on the 1960s Lagos art scene. Each influenced Nigerian modernism. This roundtable shall look at the ways in which women impact Nigeria today through their art and advocacy. How do women become successful contemporary artists in Nigeria? Does advocacy mean that their art remains gendered? How does gender affect patronage, the global art market? Confirmed Presenters: Nike Okundaye: [email protected] Peju Alatise: [email protected] 250-word Abstract: Contemporary art in Nigeria is fascinating due in no small part to women. This roundtable looks at the work and the history of Nigeria’s female artists. Collette Omogbai, Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu and Afie Ekong are pioneering firsts: each influenced Nigerian modernism. Omogbai was the first woman to receive an arts education; Ugbodaga-Ngu during the 1950s was the only Nigerian faculty member at Zaria’s Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology (NCAST), and, Ekong wielded considerable influence on the 1960s Lagos art scene. Today, Nike Okundaye, and Peju Alatise, are perhaps two of Nigeria’s best-known advocates for gender equity. Often working without the safety net of conventionality, each with laser focus, exposes particular problems within Nigeria. -

Textiles in Art, Fashion, and Cultural Memory in Nigeria Since 1960

The Pattern of Modernity: Textiles in Art, Fashion, and Cultural Memory in Nigeria since 1960 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the Department of History and Cultural Studies of Freie Universität Berlin By: Erin Michelle Rice Berlin, 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Wendy M.K. Shaw Second examiner: Prof. Dr. Tobias Wendl Date of defense: 16 July 2018 Grade: Magna Cum Laude 2 ABSTRACT The Pattern of Modernity: Textiles in Art, Fashion and Cultural Memory in Nigeria since 1960 This thesis explores the appropriation of printed and tie-dyed textiles in visual art and culture produced in Nigeria since 1960. By examining the social and political functions of the Yoruba indigo dyed fabric called adire as they evolved over the 20th century, the analyses of artistic appropriations are informed by the perspectives and histories of the cultural production of women in Nigeria's southwest dyeing centers. Questions related to gendered production of both "traditional crafts" and "modern art" are raised and reformulated for the specific context of textiles. Additionally, the ideology of 'Natural Synthesis' that was a formative force for the post-Independence generation of artists is considered as an influence on the drive to appropriate textiles and their patterns, as well as to conceive of them as "traditional" culture within an artistic paradigm of tradition and modernity. It argues that appropriations of textiles by modernist artists seize and sometimes erase the modernity of female and indigenous cultural production. Since these late modernist movements, artistic appropriations of textiles have continued within the field of visual arts, but underwent significant evolution in terms of media, subject matter, and conceptual underpinnings. -

Roundtables Seeking Participants

Arts Council of the African Studies Association Roundtables Seeking Participants ACASA members, please submit papers to roundtable chairs by January 31, 2017 17th Triennial Symposium on African Art University of Ghana, Legon Campus Institute of African Studies August 8-13, 2017 www.acasaonline.org ROUNDTABLE TITLE: Women and Contemporary Nigerian Art: reception, support, and patronage Contemporary art in Nigeria is fascinating due in no small part to women. This roundtable looks at the work and the history of Nigeria’s female artists. Collette Omogbai, Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu and Afie Ekong are pioneering firsts: each influenced Nigerian modernism. Omogbai was the first woman to receive an arts education; Ugbodaga-Ngu during the 1950s was the only Nigerian faculty member at Zaria’s Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology (NCAST), and, Ekong wielded considerable influence on the 1960s Lagos art scene. Today, Nike Okundaye, and Peju Alatise, are perhaps two of Nigeria’s best-known advocates for gender equity. Often working without the safety net of conventionality, each with laser focus, exposes particular problems within Nigeria. Through the use of Yoruba folklore, they have shown spotlights on forced marriage, misogyny, and, tradition. Eschewing the feminist label, both have boldly chosen their own path. They are the continuum of the work of Nigeria’s first women artists. Neither ascribe to western labels, instead they rewrite the ways in which the contemporary arts of Nigeria are to be received on the global stage. Both demand that the work is accepted for what it is rather from whence it hails. This roundtable shall look at the ways in which women impact Nigeria today through their art and advocacy. -

Iconoclash Or Iconoconstrain Truth and Consequence in Contemporary Benin B®And Brass Castings

Iconoclash or Iconoconstrain Truth and Consequence in Contemporary Benin B®and Brass Castings Joseph Nevadomsky YOU WANT THE TRUTH? YOU CAN’T HANDLE THE TRUTH. cally strategic, at the same time. The documented barricade —JACK NICHOLSON AS COL. JESSUP, IN A FEW GOOD MEN (1992) disarticulates the post-1897 production of cast objects from pre- 1897 castings, creating a dichotomy between categorizations— … UNTIL THE LIONS HAVE THEIR OWN HISTORIANS, THE Euro-American aesthetics and art trade vs. Benin civic efficacies HISTORY OF THE HUNT WILL ALWAYS GLORIFY THE HUNTER. and power memory objects—and in the end constitutes an intel- —CHINUA ACHEBE, THE ART OF FICTION (1994:3) lectual dissociation. The date disenfranchises twentieth century Benin castings at the same time that it adds substantial worth to pre-boundary objects. One has somehow to deconstruct the n his introduction to the exhibition catalogue Icono- border crossing between classical Benin art and contemporary clash Bruno Latour (2002) questions the (art) histori- Benin art as exemplified by the temporal cutoff. The difference cal narrative of modernity and turns it into a matter of in merit/value between an object made in the 1890s and, say, doubt. What happens, he asks, if iconoclasm is not a another made ca. 1900–1920 is in the perception of the com- definite dividing line between those who commit the modity as dictated by the date. Scavenging canonical castings hideous act of breaking images and those who don’t? result in few pickings these days, and a change in the academic What if we are all iconoclasts and what if we only differ by the weather makes a paradigm shift likely. -

P40 Layout 1

Justin Bieber wins 3 MTV EMA Europe music38 awards TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 8, 2016 Hostesses pose for photograph during the All Africa Music Awards (AFRIMA) ceremony in Lagos Sunday. 82-year-old Cameroonian vibraphone and saxophonist Manu Dibango, was recognized for making tremen- dous contributions to African music, especially for developing a music style fusing jazz, funk and traditional Cameroonian music. The All Africa Music Awards is designed to recognize and reward artiste who have given African music the most creative competitive edge in the global market within the year under review. — AFP Nigerian artists keep sculpture in the family Nigeria’s first female bronze caster Princess Elizabeth Olowu (right) poses Artist and art historian Peju Layiwola answers journalists’ questions in Nigeria’s first female bronze caster Princess Elizabeth Olowu, 77, cleans with eldest daughter Peju Layiwola, also an artist and art historian in her Benin City. her bronze sculptures with lemon juice in her living room. living room in Benin City. — AFP photos rincess Elizabeth Olowu, 77, sits on the A supportive father of the “Benin Bronzes”, which were stolen by Greek mythology and Yoruba mythology,” meaning.” Olowu dusts her sculptures to give sofa in her small living room, rubbing In Benin City, superstition had it that if a the British during colonial times and which she says, flicking through photographs on them their original shine. Pbronze sculptures with lemon juice to woman went into a foundry-particularly when largely remain in museums overseas. her computer. “She is very close to her work, so I don’t make them shine. -

BOUNDARY OBJECTS June 20 – September 20, 2015 Kunsthaus Dresden – Municipal Gallery for Contemporary Art

Artificial Facts BOUNDARY OBJECTS June 20 – September 20, 2015 Kunsthaus Dresden – Municipal Gallery for Contemporary Art Kader Attia (Berlin/Algier) Burning Museum (Cape Town) Sammy Baloji / Lazara Rosell Albear (Havanna/Brüssel) Peju Layiwola (Lagos) Michelle Monareng (Johannesburg) Paulo Nazareth (Belo Horizonte) Lisl Ponger (Wien) Jorge Satorre (Mexico City/Barcelona) Penny Siopis (Cape Town) Dierk Schmidt (Berlin) Karl Waldmann (†) Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa (London/Innsbruck/Kampala) curated by Sophie Goltz (Hamburg/Berlin) BOUNDARY OBJECTS The showcases of the Ethnological Museum are shattered. Current debates in discourse among museums and in contemporary art are focusing on the future of European and African collections whose historical origins are directly tied to colonial geographies and ethnographies. In the light of the historical situation—the racist practice of human zoos, colonial exhibitions, medical-historical collections to classify humans, and one of the most extensive ethnological collections in Europe—questions related to restitution, the treatment of human remains and cultural heritage are attaining significance also for Dresden and Saxony. With the exhibition Boundary Objects, the research and exhibition project Artificial Facts (2014/2015) opens its third and final station in Dresden, following Cape Town (South Africa) und Porto-Novo (Benin). Works by international artists, partly created especially for the exhibition, pose a challenge to the visual colonization of the museal gaze, examining established visual regimes and calling the gestures of displays and representation—and ultimately the construction of the “other” in the museum—into question. The artists are interested in the future status of objects that were once collected as pieces of cultural-historical evidence, as souvenirs and trophies, and are today increasingly attributed to a globalized World Art.