Bruce Onobrakpeya and the Harmattan Workshop Artistic Experimentation in the Niger Delta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

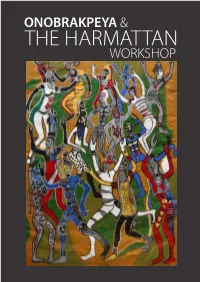

Onobrakpeya & Workshop

ONOBRAKPEYA & THE HARMATTAN WORKSHOP 78 Ezekiel Udubrae (detail) AGBARHA OTOR LANDSCAPE 2007 oil on canvas 122 x 141cm 78 Ezekiel Udubrae (detail) AGBARHA OTOR LANDSCAPE 2007 oil on canvas 122 x 141cm ONOBRAKPEYA & THE HARMATTAN WORKSHOP 1 Bruce Onobrakpeya OBARO ISHOSHI ROVUE ESIRI (THE FRONT OF THE CHURCH OF GOOD NEWS) plastocast 125 x 93 cm 3 ONOBRAKPEYA & THE HARMATTAN WORKSHOP 1 Bruce Onobrakpeya OBARO ISHOSHI ROVUE ESIRI (THE FRONT OF THE CHURCH OF GOOD NEWS) plastocast 125 x 93 cm 3 ONOBRAKPEYA & THE HARMATTAN WORKSHOP CURATED BY SANDRA MBANEFO OBIAGO at the LAGOS COURT OF ARBITRATION SEPT. 16 - DEC 16, 2016 240 Aderinsoye Aladegbongbe (detail) SHOWERS OF BLESSING 2009 acrylic on canvas 60.5 x 100cm 5 ONOBRAKPEYA & THE HARMATTAN WORKSHOP CURATED BY SANDRA MBANEFO OBIAGO at the LAGOS COURT OF ARBITRATION SEPT. 16 - DEC 16, 2016 240 Aderinsoye Aladegbongbe (detail) SHOWERS OF BLESSING 2009 acrylic on canvas 60.5 x 100cm 5 We wish to acknowledge the generous support of: Lead Sponsor Sponsors and Partners Contents Welcome by Yemi Candide Johnson 9 Foreword by Andrew Skipper 11 Preface by Prof. Bruce Onobrakpeya 13 Curatorial Foreword by Sandra Mbanefo Obiago 19 Bruce Onobrakpeya: Human Treasure 25 The Long Road to Agbarah-Otor 33 Credits Celebration by Sam Ovraiti 97 Editorial & Artistic Direction: Sandra Mbanefo Obiago Photography, Layout & Design: Adeyinka Akingbade Our Culture, Our Wealth 99 Exhibition Assistant Manager: Nneoma Ilogu Art at the Heart of Giving by Prof. Peju Layiwola 121 Harmattan Workshop Editorial: Bruce Onobrakpeya, Sam Ovraiti, Moses Unokwah Friendships & Connectivity 133 BOF Exhibition Team: Udeme Nyong, Bode Olaniran, Pius Emorhopkor, Ojo Olaniyi, Oluwole Orowole, Dele Oluseye, Azeez Alawode, Patrick Akpojotor, Monsuru Alashe, A Master & His Workshops by Tam Fiofori 149 Rasaki Adeniyi, Ikechukwu Ajibo and Daniel Ajibade. -

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

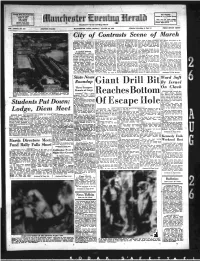

Roundup Giant Drill Bit Reaches Bottom of Escape Hole

..--'.■I- - :i: n'- y 'r \ 'f ■itti Arwag* Daily Net Press Ron T h e W «B th«r Vor ttke Week Ended raramal o f D. « . WmUimr B n s a a August S4, IM S ■ Clear and eool again toolglit. 13,521 Low 48 Is SO. Tuesday mm aj imd Member at the Audit plrassnt. High near W. Bwresu of Obvulstlaa , M aneh^ter-^A City o f ViUage Charm (assstfied AdserlMng m b Fug* 16) PRICE SEVEN CENTS' ▼OL. LXXXU, NO. 278 (SIXTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAlT, AUGUST 26, 1963 City af Contrasts Scene of March plex of greenery and, marble, a the same tinve. Although the crime lems. Most of these committees there without intermittent or bil EDITOR'S NOTE — The nation’s ious fever.’’ attention.. focuses Wednesday on monument that looks east to the has received wide and often lurid are ruled by Southerners. Some Capitol, north to the White House' publicity, it differs llttie from residents say these congressmen Like India's New Delhi and Washington when thousands of Brazil’s Brasilia. Washington is a civil lights advocates mass to west to the Lincoln Memorial and crime rates in other big cities have no sympathy for a 67 per south to the JTefferson Memorial of America. Washington is ninth cent Negro city with Integrated city created as a capital, with no dramatize the struggle for Negro other reason for life. It does not rights. The city that awaits them and the Tidal Basin rimmed with in size with a population of 764,- schools w d restaurants and is sketched In the following ar cherry trees. -

British-Village-Inn-Exhibition-March

MISSION To identify talented Nigerian Female Artists to bring positive social change in society. VISION To foster a sense of pride and achievements among female creative professionals. To promote the dignity of women. To encourage membership to continue creating art. FEAAN EXCECUTIVE MEMBERS President Chinze Ojobo Vice President Clara Aden Secretary Abigail Nnaji Treasurer Millicent Okocha Financial Secretary Funmi Akindejoye P.R.O. Chinyere Odinikwe Welfare Officer Amarachi K. Odimba TOP MANAGEMENT Chairman BoT Prof Bridget O. Nwanze Secretary BoT Lady Ngozi Akande President Chinze Ojobo FEAAN Representative Susa Rodriguez-Garrido 02 FEMALE ARTISTS A S S O C I AT I O N O F N I G E R I A Copyright © 2019 ISBN NO: 978-978-972-362-1 A Catalogue of Exhibition Female Artists Association of Nigeria All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the copyright owner and publishers. CURATORS Susa Rodriguez-Garrido Chinze Ojobo GRAPHICS Susa Rodriguez-Garrido Rotimi Rex Abigail Nnaji PUBLISHER ImageXetera 03 CONTENT Foreword by the President of the Female Artists Association of Nigeria. Chinze Ojobo................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Preface by Susa Rodriguez-Garrido, Representative of FEAAN, Founder of Agama Publishing Susa Rodriguez-Garrido........................................................................................................................................... -

English Or French Please Provide the Name of the Organization in English Or French.·

NG0-90423-02 ... : NGO accreditation ICH-09- Form ReC?u CLT I CIH I ITH United Nations Intangible :ducational, Scientific and Cultural Cultural Organization Heritage Le 0 3 SEP. 201~ N° ..........O.f!.{J ..... .. ...... REQUEST BY A NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION TO BE ACCREDITED TO PROVIDE ADVISORY SERVICES TO THE COMMITTEE DEADLINE 30 APRIL 2019 Instructions for completing the request form are available at: fl11ps://icl1. unesco. orl/lenlforms 1. Name of the organization 1.a. Official name Please provide the full official name of tile organization, in its original language, as it appears in the supporting documentation establishing its legal personality (section 8.b below). Centre for Black Culture andlnternational Understanding, Osogbo 1.b. Name in English or French Please provide the name of the organization in English or French.· lCentre for Blac;-Culture and International Understanding, Osogbo 2. Contact of the organization 2.a. Address of the organization Please provide tl1e complete postal address of the organization, as well as additional contact information· such as its telephone nurn/Jer, email address, website, etc. This sfJould be the postal address where the organization carries out ifs business, regardless of wile re it may /;e legally domiciled (see section 8). Organization: Centre for Black Culture and International Understanding, Osogbo Address: Government Reserved Area, Abere, Osun State Telephone number: + 231812369601 0 Email address: [email protected] Website: www.centreforblackcullure.org Other relevant information: L---- f-orm ICH-09-2020-EN- revised on 26/07/2017- oaoe 1 --- ------- 2.b Contact person for correspondence Provide the complete name, address and other contact information of the person responsible for correspondence conceming this request Title (Ms/Mr, etc }: Mr Family name : Ajibola G1ven name. -

Visual Art Appreciation in Nigeria: the Zaria Art Society Experience

Mgbakoigba, Journal of African Studies. Vol.6 No.2. February 2017 VISUAL ART APPRECIATION IN NIGERIA: THE ZARIA ART SOCIETY EXPERIENCE Chinyere Ndubuisi Department of Fine Art, Yaba College of Technology, Yaba, Lagos, Nigeria [email protected] 0802 3434372 Abstract There is no doubt that one of the greatest creative impetuses injected into Nigerian art was made possible by, among other things, the activities of the first art institution in Nigeria to award a Diploma certificate in art, Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology (NCAST). NCAST started in 1953/54 at their Ibadan branch but they could not rationalize their art programme ab initio but organized art exhibition to raise the public awareness of the programme. In September 1955 the art programme became a full department and relocated to their permanent site at Zaria, in northern Nigeria, with 16 students. This paper focuses on NCAST impact on modern Nigerian art and the gradual, but steady, growth of other art activities in Nigeria since NCAST. The paper also discusses the emergence of an art society from NCAST, known as Zaria Art Society and the extension of the philosophy of the Art Society into the church by one of its member, Bruce Onobrakpeya, who represented most of his Christian images in traditional Urhobo style as against the popular western style. The paper argues that Nigeria has a rich art and diverse culture which existed long before the colonial reign and thus encouraged the efforts of the Zaria Art Society in re-appropriating local forms and motifs in their modern art by way of an ideology known as 'Natural synthesis.' Introduction The argument may be how one can define 'culture' in the context of the diverse ethnic groups that populate present-day Nigeria. -

Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria'

H-AfrArts Smith on Okeke-Agulu, 'Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria' Review published on Tuesday, October 4, 2016 Chika Okeke-Agulu. Postcolonial Modernism: Art and Decolonization in Twentieth-Century Nigeria. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015. 376 pp. $99.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-8223-5732-2; $29.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-8223-5746-9. Reviewed by Fred Smith (Kent State University)Published on H-AfrArts (October, 2016) Commissioned by Jean M. Borgatti The Development of Contemporary Nigerian Painting from the Early Twentieth Century to Uche Okeke and Demas Nwoko Chika Okeke-Agulu’s book on art and decolonization is an extensive and highly detailed investigation of the emergence of artistic modernism in Nigeria from the late 1950s to the civil war in 1967. However, it focuses primarily on artists who began their career as art students at the Nigeria College of Arts, Science, and Technology in Zaria. The book is especially concerned with the varied connections between local artistic developments and twentieth-century modernism. It also relates these connections to the cultural and political conditions of Nigeria as it transitioned from British colony to independence. The investigation begins with evaluating the colonial impact, especially that of indirect rule and its political implications on education, especially art education, during the early to mid-twentieth century. Chapter 1 (“Colonialism and the Educated Africans”) investigates the nature of the colonial experience and how it was affected by educated Africans. The discussion considers Anglophone Africa in general but primarily focuses on Nigeria. Various colonial administrators and their policies, including those impacting educational opportunities, are evaluated. -

Of Gerald Chukwuma: a Critical Analysis

arts Article Visual Language and ‘Paintaglios’ of Gerald Chukwuma: A Critical Analysis Trevor Vermont Morgan, Chukwuemeka Nwigwe and Chukwunonso Uzoagba * Department of Fine and Applied Arts, University of Nigeria, Nsukka (400241), Nigeria; [email protected] (T.V.M.); [email protected] (C.N.); [email protected] (C.U.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +234-806-444-0984 Academic Editor: Annetta Alexandridis Received: 23 September 2016; Accepted: 28 April 2017; Published: 24 May 2017 Abstract: Gerald Chukwuma is a prolific Nigerian artist whose creative adaptation and use of media tend to deviate from common practice. This essay draws on his several avant-garde works on display at the Nnamdi Azikiwe Library and at the administrative building of the University of Nigeria Nsukka. These artworks are referred to as ‘paintaglio’ in this essay owing to the convergence of painting, and engraving (or intaglio) processes. This study therefore identifies, critically interprets and analyzes Chukwuma’s artistic inclinations—style, spirit, forms, materials, and techniques. This is in order to lay bare the formal and conceptual properties that foreground the artist’s recent paintaglio experiments. The study relies on personal interviews, literature, and images of Chukwuma’s works as data. Such experimental works which clearly express influences of ‘natural synthesis’ ideology are here examined against the backdrop of their epistemic themes. Keywords: paintaglio; experimental art; self-discovery; creative; visual; uli; Nsukka School 1. Introduction Nigerian artist Chike Aniakor’s view of creativity as “the wandering of human spirit from one level of experience to another,” until it has secured a desired venting point lends credence to Dante Rossetti’s understanding that fundamental brainwork makes art unique (Aniakor 1987, p. -

Abstract African-American Studies Department

ABSTRACT AFRICAN-AMERICAN STUDIES DEPARTMENT OKWUMABUA, NMADILI N. B.A. GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1994 ARCHITECTURAL RETENTION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN AFRICAN DESIGN IN THE WORKS OF ARCHITECT DEMAS NWOKO, Major Advisor: Dr. Daniel Black Thesis dated May 2007 The purpose of this research was to examine elements of traditional African architecturai design in fhe works of Demas Nwoko. These elements remain aesthetically - and functionally valuable; hence, their inclusion in the development of modern African residential architecture. The research simultaneously explores the methodology Nwoko has created to apply his theory of comfort design in architecture, as well as the impact of traditional Afi-ican culture and European culture on modem African residential design. The methodology used is visual analysis, as several of Nwoko's buildings were visited, photographed and analyzed for the application of his design ideology of New Culture. The three elements of design examined are his approach to space design that supports lifestyle and achieves comfort; artistic application that reflects African aesthetic values in color, motif and design patterns; and his use of building materials, that not only provide comfortable interiors in a tropical climate, but are affordable and durable. The research concludes with recommendations and contributions to the discourse on modern Afiican design and offers the findings for fwther research and development of African and Diaspora communities. The findings expose the intrinsic value of culture and architectural retention in the evolution of modem architecture in Africa and the Diaspora. ARCHITECTURAL RETENTION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF MODERN AFRICAN DESIGN IN THE WORKS OF ARCHITECT DEMAS NWOKO A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR TIE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY NMADILI N. -

Ethnic Traditions, Contemporary Nigerian Art and Group Identity

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.47, 2016 Ethnic Traditions, Contemporary Nigerian Art and Group Identity Dr. Samuel Onwuakpa Department of Fine Arts and Design, University of Port Harcourt, Rivers State Nigeria Dr. Efe Ononeme Department of Fine and Applied Arts University of Benin , Edo State Nigeria Introduction Contemporary Nigerian artists like their counterparts in different parts of Africa have drawn some of their inspirations from traditional art and life and in so doing they have not only contributed to the creation of an amalgamated national identity, but also continue to give art tradition a lifeline. The creative and visual talents noticed among many Nigerians artists no doubt is an indication that they have responded to the dynamics of change and continuity within the frame-work of indigenous art and culture. Generally, but not exclusive, Igbo and Yoruba cultures are characterized by strong art traditions and a rich art vocabulary from which some contemporary artists drew from. Thus it is no surprise that it has enriched their creativity. As the artists draw from Igbo and Yoruba cultures for identity, there is continuity not a break with the past. Among other things, this study focuses on the contemporary artists who study and adapt forms, decorative motifs and symbols taken from indigenous arts and craft of the Yoruba Ona and Igbo Uli for use in their works. -

![[1] Ui Thesis Olasupo A.A Yoruba 2015 Full Work.Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3265/1-ui-thesis-olasupo-a-a-yoruba-2015-full-work-pdf-983265.webp)

[1] Ui Thesis Olasupo A.A Yoruba 2015 Full Work.Pdf

i YORÙBÁ TRADITIONAL RELIGIOUS WOOD-CARVINGS BY AKANDE ABIODUN OLASUPO B. A. (Hons.) Fine Arts ( ), M. A. Visual Arts (Ibadan), PGDE (Ado-Ekiti) A Thesis in the Department of VISUAL ARTS Submitted to the Institute of African Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN LIBRARY MAY 2015 ii ABSTRACT The Yorùbá -Yorùbá N O - - Yorùbá traditional religion and its attendant practice of wood-carving. Existing studies on Yorùbá wood-carving have concen -Yorùbá existed independently for a long time. This study, therefore, identified extant Yorùbá examined areas of divergence in the artistic production of the people. - wood-carvers, priests and adherents of some Yorùbá traditional religion who use wooden paraphernalia in their worship. Direct observation was used to collect data on iconographic features of wooden religious paraphernalia such as ọpón-Ifá (divination board), agere-Ifá (palm-nut bowl), ìróké-Ifá (divination board-tapper), osé-Ṣà Ṣà ‟ ère-ìbejì (twin figurines), and egúngún and gèlèdé masks. The interviews were content-analysed, while the paraphernalia were subjected to iconographic, semiotic and comparative analyses. UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN LIBRARY Opón-Ifá, agere-Ifá, ìróké-Ifá, osé-Ṣà and ère-ìbejì Gèlèdé ìróké-Ifá, agere-Ifá and osé-Ṣà shared similar iconographic fe by the top, middle and base sections. Their middle sections bore a variety of iii images, while the top and base sections were fixed. In all the three communities, the face of Èsù, usually represented on ọpón-Ifá, was the only constant feature on divination trays. Other depictions on the tray varied from zoomorphic and anthropomorphic to abstract motifs. -

Ceramics As a Medium of Social Commentary in Nigeria

Bassey Andah Journal Vol.6 Ceramics as a Medium of Social Commentary in Nigeria Ozioma Onuzulike, & Chukwuemeka Nwigwe & May Ngozi Okafor Abstract This paper proposes that a number of Nigerian ceramic artists and sculptors who have experimented with the ceramic medium have considerably engaged with socio-political issues, especially in form of satires and critical commentaries over post-independence politics, politicians and the Nigerian state. It examines the history of critical engagements with the ceramic medium in postcolonial Nigeria and attempts a critical appraisal and analysis of the works of important socially- committed ceramic artists in the country in terms of the themes of conflict and how they intersect with post- independence politics, politicians and the Nigerian state. Key Words: Ceramics, Social Commentary, Nigerian art, ceramic artists Introduction Traditional African societies are known to have had forms of social control, which included the use of satires, songs, folklores, and other creative channels to extol the good and castigate the evil. Their songs, riddles and proverbs were largely didactic and socially-oriented. This creative attitude goes back to primordial times. World art history has often drawn attention to the work of cave artists of the Palaeolithic era when art served as a means of survival and self- preservation. It has been argued that the paintings of the cave artists were not merely decorative; else, they would not have been executed at the uninhabited and hidden parts of the caves (Gardner 1976). This is also true of rock-shelter paintings such as the popular Marching Warriors, a picture executed during the Mesolithic period in Spain and which dated about 8000-3000 BC.