Achievement Report to 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MID TERM PROGRESS REPORT Table of Contents

Family and Domestic Violence Unit Western Australia Strategic Plan for FAMILY AND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE 2009-2013 MID TERM PROGRESS REPORT Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................................2 STATE GOVERNANCE AND REPORTING FRAMEWORK .................................................................................4 NATIONAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................................................5 OUTCOME ONE: PREVENTION AND EARLY INTERVENTION .........................................................................7 Strategy Links ..............................................................................................................................................7 Initiatives .....................................................................................................................................................7 OUTCOME TWO: SAFETY FOR VICTIMS ......................................................................................................9 Strategy Links ..............................................................................................................................................9 Initiatives .....................................................................................................................................................9 OUTCOME THREE: ACCOUNTABILITY FOR PERPETRATORS ......................................................................14 -

Submission on Privacy and Responsible Information Sharing

Western Australia Police Force Submission on Privacy and Responsible Information Sharing October 2019 CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................... 1 1.1 Key recommendations (8 of 18) 1 2.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 2 3.0 WESTERN AUSTRALIA POLICE FORCE ........................................................... 2 4.0 PRIVACY IN A LAW ENFORCEMENT CONTEXT ............................................... 3 4.1 Safer communities 3 4.1.1 Victim support 3 4.1.2 Community safety 3 4.1.3 Improved social outcomes 3 4.1.4 Research supporting community and road safety 4 4.2 Prevent crime and enforce the law 4 4.2.1 The efficacy of law enforcement and the collection, notification, use and disclosure of personal information 4 Collection 5 Notification 5 Use or disclosure 6 4.3 Supporting outcomes of other government agencies 7 4.3.1 Information sharing, compliance and governance 7 4.4 Access to and correction of personal information 8 4.4.1 Release mechanism outside of the FOI process 8 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Privacy and information sharing in the sphere of law enforcement presents unique challenges. As a police force representing the interests and rights of the community, we must strike a balance between protecting the broader community and an individual’s right to privacy. The Western Australia Police Force submits that the below key recommendations address the key threshold issues that may lessen or advance our ability to provide better policing services to the community of Western Australia. 1.1 Key recommendations (8 of 18) 1. There be a presumption in favour of a victim or their representative, to have the right to know the identity of an alleged offender. -

POLICE DEPARTMENT WESTERN AUSTRALIA Ephemera PR8867

J S Battye Library of West Australian History Collection POLICE DEPARTMENT WESTERN AUSTRALIA Ephemera PR8867 To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia . CALL NO. DESCRIPTION PR8867/1 Judges Rules & Preliminary Breath Test Requirements, pamphlet, 1978. D PR8867/2 Blood Alcohol Sampling Regulations, pamphlet, 1977. D PR8867/3 Item Missing 15th December 1994. PR8867/4 Item Missing 15th December 1994 PR8867/5 The Pioneer Years: a Pictorial History of W.A. Police Stations by Constable Henry James McLaughlin - A List of Paintings, March 1977. D PR8867/6 Protect Your Home, pamphlet, 1977. D PR8867/7 The Police & The Public, pamphlet, 1966. D PR8867/8 Special Circular: Murder Unidentified Body - Dental Examination Report by Dr. Frank Digwood, October 1979. D PR8867/9 Introduction to a Career in the W.A. Police Force, pamphlet, 1968. D PR8867/10 Air Patrol Section, 1 p. sheet, 1982. D PR8867/11 Radar Speed Detection Devices, 2p. Notice, 1982. D PR8867/12 This Bicycle does not conform with the vehicle standard regulations, 2 p. Pamphlet. 1982. D D PR8867/13 Notice to Horse Float owners, 2p. Pamphlet. 1982. D PR8867/14 "If Everyone" Drive Safely Pamphlet, 1982. D PR8867/15 If You Drink & Drive - You Should Know About the Quietest Room in Town, pamphlet, 1982. D PR8867/16 Covering of Grain Vehicles: Advice to Farmers, pamphlet, 1982. D PR8867/17 What every Visiting Driver Should Know, 2p. Pamphlet. 1982. D PR8867/18 Breathalyser, pamphlet, 1982. D PR8867/19 You have been involved in a Traffic Accident...What now? Booklet. 1982. -

Legislative Assembly

Legislative Assembly Thursday, 27 November 2008 THE SPEAKER (Mr G.A. Woodhams) took the chair at 9.00 am, and read prayers. TRUTH-IN-SENTENCING LAWS Petition MR A.J. SIMPSON (Darling Range — Parliamentary Secretary) [9.02 am]: I have a petition that has been certified as conforming to the standing orders of the Legislative Assembly and has been signed by 210 petitioners. It reads as follows — To the Honourable the Speaker and Members of the Legislative Assembly of the Parliament of Western Australia in Parliament assembled. We, the undersigned, say that the ‘truth in sentencing’ laws enacted by the Labor State Government that automatically reduce all sentences by 1/3rd do not represent community expectations. Now we ask the Legislative Assembly to repeal these laws which make a mockery of Western Australia’s criminal justice system. [See petition 21.] ROEBOURNE PCYC Petition MR V. CATANIA (North West) [9.03 am]: I have a petition with 26 signatures that reads as follows — To the Honourable the Speaker and Members of the Legislative Assembly of the Parliament of Western Australia in Parliament assembled. We, the undersigned, say that the Roebourne PCYC is an important community asset and is a key hub of activity for local young people. The role that the PCYC plays in diverting children at risk, away from criminal activity and anti-social behaviour is a valuable one. Similarly the opportunity for the young to interact with positive role models and to develop trusting relationships with police is an investment in the future of our community. The possible closure of the PCYC would have major implications as alternatives which would achieve the same outcomes are neither feasible nor available. -

WA+Police+Vol+2+Part+2.Pdf

FINAL REPORT APPENDIX A EXAMPLE OF METROPOLITAN INTERNAL INVESTIGATION FILE The complainant in this matter was well known to internal investigators and the Ombudsman. The complaint concerned a search of the complainant's home, which, as a precaution, was video, taped from start to finish. The video tape provides evidence that the police officers involved acted with restraint in difficult circumstances. 19 August 2002 Incident occurs. Complaint lodged at police station and first advice note compiled. 17 September 2002 District compiles second advice note and forwards to IIU. 27 September 2002 IIU compiles third advice note and forwards to Ombudsman. Regional Commander advised and instruction to investigate forwarded to District Superintendent. 4 October 2002 District Co-ordinator receives IIU papers. 7 October 2002 District Co-ordinator advises IIU of file allocation details. 8 October 2002 District Superintendent forwards paper to OIC of workplace for investigation. 9 October 2002 OIC advises District Superintendent of unavailability to investigate. File reallocated with note that it is to be completed by 8 November 2002. 31 October 2002 Investigation commences. 5 March 2003 Investigation report completed and forwarded to District Co- ordinator. 7 March 2003 District Co-ordinator forwards file to District Superintendent, who agrees and forwards to IIU. 10 March 2003 District Superintendent writes to complainant. 12 March 2003 IIU sends file to Ombudsman for review. 14 March 2003 File received at Ombudsman's Office. INVESTIGATION TIME - 4 months (57 per cent) ADMINISTRATION TIME - 3 months (43 per cent) TOTAL TIME - 7 months PAGE 228 CHAPTER 9 – COMPLAINTS Appendix B EXAMPLE OF COUNTRY INTERNAL INVESTIGATION FILE In this matter the complainant alleged assault. -

WA Police Strategic Policy on Police and Aboriginal People

Western Australia Police Service Strategic Policy on Police and Aboriginal People A strategic approach to working with Aboriginal1 people in providing equitable and accessible policing services Policy Statement and Rationale 1 Consistent with the Aboriginal Justice Agreement, the term ‘Aboriginal people’ used in this Policy is used to refer to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, where appropriate. Strategic Policy on Police and Aboriginal People I. Introduction A focus on delivering appropriate services to the community has resulted in the development of strategic policies in the three key areas of services to youth, services to Aboriginal people and our approach to family and domestic violence. This is consistent with the Strategic Plan of the Police Service, which identified services to youth and Aboriginal people as priority areas. Family and domestic violence was also identified as a strategic issue. This document presents a strategic policy providing a corporate position on services to, and the relationship with, Aboriginal people. There are linkages between the three policy statements on a number of levels that emphasise the reality that the Police Service does provide a disproportionate level of services to certain socio-demographic groups. The suite of these three strategic policies identifies issues that impact particularly on young people and Aboriginal people, who also represent the largest proportion of victims of crime and offenders in Western Australia. The policy statement itself is a concise expression of the intent of the agency, its commitment to dealing with the specific issues covered by the policy and an indication of the strategic direction. The policy statement can stand alone in the strategic sense, but the accompanying framework does provide the fullest expression of how and why the policy came to be and how the agency expects it to guide agency planning and practices. -

Western Australia Police Case Study

WESTERN AUSTRALIA POLICE CASE STUDY IDEASCALE IdeaScale Case Studies 2 Western Australia Police Giving ownership of innovation to a workforce that covers 2.5 Million Square Kilometers Western Australia Police is one of eight police jurisdictions in Australia and is responsible for policing the world's largest single geographic jurisdiction. Covering 2.5 million square kilometers, WA Police is made up of 11 districts and 157 police stations, with a unique spread across a major capital city (Perth), regional towns, rural areas and vast remote locations. The population of Western Australia is growing at a rate that will likely see demand for policing services exceed resources. To address this, WA Police launched Frontline 2020, a major reform program that continues to examine all aspects of policing services in order to become even more efficient, productive, and locally-focused. A key element of the Frontline 2020 initiative was the establishment of the Continuous Improvement Team (CIT) to source and select ideas from a workforce of 8,000 officers and public servants. This team used IdeaScale to develop a Frontline Innovation Portal to capture and promote those workforce ideas, particularly those around reducing ‘red-tape’ and unnecessary process. The CIT was able to launch the first version of the portal within a day on IdeaScale and present it to the executive team that evening, allowing the project to be fast-tracked. WA Police approved all members to its community by asking them to sign on with their work email address and disabled anonymous submission in order to encourage transparency. To start the conversation, the CIT promoted their IdeaScale community in a weekly newsletter, in workshops with senior leadership and the CIT, and changed all work desktops to show an invitation to the Frontline Innovation Portal. -

WAPOL-Overview--20190702.Pdf

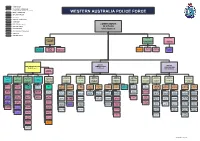

COMMISSIONER ROAD SAFETY COMMISSIONER Formally reports to the Minister for Police; Road Safety DEPUTY COMMISSIONER WESTERN AUSTRALIA POLICE FORCE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SOLICITORS ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER COMMANDER DIRECTOR/CIO (CLASS 1) COMMISSIONER DIRECTOR (LEVEL 9) OF POLICE SUPERINTENDENT Chris Dawson ASSISTANT DIRECTOR (LEVEL 8) INSPECTOR MANAGER (LEVEL 7) DIRECTOR CHIEF OF STAFF COMMISSIONER ROAD SAFETY MEDIA & CORPORATE OFFICE OF COMMISSION COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSIONER MEDIA & CORPO RAT E FINANCE & EXECUTIVE AND STRATEGY POLICY COMMUNICATION & POLICE MEDIA CONTENT COMMUNICATIONS BUSINESS MINISTERIAL & LEGISLATION ENGAGEMENT SERVICES SERVICES DEPUTY DEPUTY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER Frank Pasquale Col Blanch Gary Dreibergs BUSINESS MANAGEMENT CHIEF ASSISTANT CHIEF FINANCE DIRECTOR DIRECTOR ASSISTANT ASSISTANT ASSISTANT ASSISTANT ASSISTANT ASSISTANT ASSISTANT ASSISTANT INFORMATION ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER OFFICER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER OFFICER COMMISSIONER ASSET HUMAN SPECIALIST & STATE COMMUNITY & PROFESSIONAL FINANCE MANAGEMENT RESOURCES STATE CRIME PROFESSIONAL OPERATIONS REGIONAL WA METROPOLITAN BUSINESS INFO FORENSIC, LEGAL SUPPORT INTELLIGENCE COORDINATION STANDARDS & COMMAND DEVELOPMENT SUPPORT REGION SYSTEMS & LEGISLATION SERVICES CHIEF HEALTH, COMMANDER LEGAL COMMANDER DEPUTY CFO LAND & BUILDING TECHNOLOGY WELFARE & COUNTER COMMANDER COMMANDER DIRECTOR INTERNAL POLICE COMMANDER COMMANDER COMMANDER SERVICES COMMANDER CRIME COMMANDER -

ANNUAL REPORT REPORT 2020 20203 COMMISSIONER’S FOREWORD Thank You for Your Interest in the Western Australia Police Force Annual Report of 2020

CONTENTS COMMISSIONER’S FOREWORD .................................................................................... 4 AWARDS AND RECOGNITION ................................................................................................................................... 43 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 6 ROAD SAFETY COMMISSION ......................................................................................................................................44 OVERVIEW OF THE AGENCY ......................................................................................... 8 SUMMARY OF RESULTS AGAINST FINANCIAL TARGETS .........................................................51 AGENCY AT A GLANCE .............................................................................................................................................................8 SUMMARY OF RESULTS AGAINST PERFORMANCE TARGETS ........................................ 52 OPERATIONAL STRUCTURE ..............................................................................................................................................9 SUMMARY OF VARIATION AGAINST PERFORMANCE TARGETS ................................. 53 REGIONS AND DISTRICTS ................................................................................................................................................ 10 SIGNIFICANT ISSUES IMPACTING THE AGENCY ....................................................54 -

Information Statement 2018 – 2019

Western Australia Police Force Information Statement 2018 – 2019 Prepared in accordance with Part 5 of the Freedom of Information Act 1992 1 | WA Police Information Statement 2017 - 2018 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. FUNCTIONS OF THE WA POLICE FORCE 4 3. WA POLICE FORCE STRUCTURE 5 4. OFFICE OF INFORMATION MANAGEMENT 6 5. PRIVACY STATEMENT 6 6. WA POLICE FORCE POLICY AND PERFORMANCE 7 7. STRATEGY AND PERFORMANCE DOCUMENTS 7 8. POLICE MANUAL 8 9. INFORMATION RELEASE CENTRE 8 9.1. PERSONAL STATEMENTS 9 9.2. NATIONAL POLICE CERTIFICATE 10 9.3. STATEMENT OF MATERIAL FACTS 10 9.4. HISTORY FOR COURT DOCUMENTATION 11 9.5. RECORD OF TRAFFIC INFRINGEMENT NOTICE 12 9.6. PERMISSIBLE INFORMATION REPORTS – CRASH AND CRIME 13 10. FREEDOM OF INFORMATION (FOI) 14 10.1. DOCUMENTS CONTAINING YOUR PERSONAL INFORMATION 14 10.2. DOCUMENTS SUBJECT TO COPYRIGHT 14 10.3. NOTICE OF DECISION 15 10.4. TIMEFRAME FOR COMPLETION 15 10.5. APPEALING A DECISION 15 10.6. AMENDING PERSONAL INFORMATION 16 10.7. APPLICATION – FREEDOM OF INFORMATION 16 2 | WA Police Information Statement 2017 - 2018 1. Introduction This Information Statement contains an overview of the structure and functions of the Western Australia (WA) Police Force, including a summary of how these functions affect members of the public and also describes methods available for the public to obtain information held by the WA Police Force. The Information Statement describes the types of documents that can be inspected, purchased or obtained with and without charge, and outlines the range of collated information reports available. The Information Statement also provides an outline of the Freedom of Information (FOI) process including how to make an FOI application, and describes relevant information specific to the WA Police Force. -

2004 Annual Report Mission in Partnership with the Community, Create a Safer and More Secure Western Australia by Providing Quality Police Services

Western Australia Police Service 2004 Annual Report Mission In partnership with the community, create a safer and more secure Western Australia by providing quality police services. Vision To be a policing service of excellence, protecting and serving the people of Western Australia. Contents Commissioner’s Foreword ............................................ 2 Hon Michelle Roberts MLA Senior Management Structure...................................... 4 Minister for Police and Emergency Services Region/Portfolio Structure ............................................ 5 Enabling Legislation...................................................... 6 In accordance with section 62 of the Publications .................................................................. 7 Financial Administration and Audit Act 1985, I hereby submit for your information and Overview of Planning and Reporting ............................ 8 presentation to Parliament, the Annual Report of the Western Australia Police Service for Key Achievements Against the year ending 30 June 2004. Government Goals........................................................ 9 This Annual Report has been prepared in Goal 1 – People and Communities ............................ 12 accordance with the provisions of the Financial Administration and Audit Act 1985. Goal 2 – The Economy .............................................. 30 Goal 3 – The Environment ........................................ 33 Goal 4 – The Regions ................................................ 34 Goal 5 – Governance -

Sick Leave and Workers' Compensation for Police Officers in Australia

Sick leave and workers’ compensation for police officers in Australia Robert Guthrie In Australia it has been necessary to enact specific provisions into industrial and employment laws to ensure workplace protection and coverage of police officers because at common law police officers have not been regarded as employees. Police unions in Australia have emerged as strong industrial players and have secured a range of terms and conditions of employment which do not apply to the broader workforce. However, the battle in relation to workers’ compensation coverage and extended sick leave seems to be ongoing, particularly in Western Australia. The area of interaction between workers’ compensation laws and sick leave entitlements is often neglected against the background of other industrial matters concerning police. This article investigates the entitlements of Australian police officers to these benefits against the historical background of industrial laws. It concludes that there is no uniformity in coverage for workers’ compensation and sick leave and that the publicly available data in relation to absence from work of police officers due to sickness are generally incomplete and present challenges for cross-jurisdictional comparisons. The article points to future areas of research into police sick leave. <DIV>INTRODUCTION Police unions have been significant, outspoken1 and successful industrial players in Australia. Police unions have been in existence in Australia since the early part of the 20th century. In fact, as early as 1917 police were given the right to argue before industrial tribunals for better pay and conditions in Queensland. Police unionism began in South Australia in 1911.2 In Western Australia, the Western Australian Police Union of Workers was formed in 1926 and registered as an industrial union.