War Torn Manchester, Its Newspapers and the Luftwaffe's Christmas Blitz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War II

World War II. – “The Blitz“ This information report describes the events of “The Blitz” during the Second World War in London. The attacks between 7th September 1940 and 10 th May 1941 are known as “The Blitz”. The report is based upon information from http://www.secondworldwar.co.uk/ , http://www.worldwar2database.com/ and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Blitz . Prelude to the War in London The Second World War started on 1 st September 1939 with the German attack on Poland. The War in London began nearly one year later. On 24 th August 1940 the German Air Force flew an attack against Thames Haven, whereby some German bombers dropped bombs on London. At this time London was not officially a target of the German Air Force. As a return, the Royal Air Force attacked Berlin. On 5th September 1940 Hitler ordered his troops to attack London by day and by night. It was the beginning of the Second World War in London. Attack on Thames Haven in 1940 The Attacks First phase The first phase of the Second World War in London was from early September 1940 to mid November 1940. In this first phase of the Second World War Hitler achieved great military success. Hitler planned to destroy the Royal Air Force to achieve his goal of British invasion. His instruction of a sustainable bombing of London and other major cities like Birmingham and Manchester began towards the end of the Battle of Britain, which the British won. Hitler ordered the German Air Force to switch their attention from the Royal Air Force to urban centres of industrial and political significance. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Reflections on Pearl Harbor Anniversaries Past Roger Dingman University of Southern California

Reflections on Pearl Harbor Anniversaries Past Roger Dingman University of Southern California By any measure, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was one of the decisive events of the twentieth century. For Americans, it was the greatest military disaster in memory-one which set them on the road to becoming the world's greatest military power. For Japanese, the attack was a momentary triumph that marked the beginning of their nation's painful and protracted transition from empire to economic colossus. Thus it is entirely appropriate, more than fifty years after the Pearl Harbor attack, to pause and consider the meaning of that event. One useful way of doing so is to look back on Pearl Harbor anniversaries past. For in public life, no less than in private, anniversaries can tell us where we are; prompt reflections on where we have been; and make us think about where we may be going. Indeed, because they are occa- sions that demand decisions by government officials and media man- agers and prompt responses by ordinary citizens about the relationship between past and present, anniversaries provide valuable insights into the forces that have shaped Japanese-American relations since 1941. On the first Pearl Harbor anniversary in December 1942, Japanese and Americans looked back on the attack in very different ways. In Tokyo, Professor Kamikawa Hikomatsu, one of Japan's most distin- guished historians of international affairs, published a newspaper ar- ticle that defended the attack as a legally and morally justifiable act of self-defense. Surrounded by enemies that exerted unrelenting mili- tary and economic pressure on it, and confronted by an America that refused accommodation through negotiation, Japan had had no choice but to strike.' On Guadalcanal, where they were locked in their first protracted battle against Japanese troops, Americans mounted a "hate shoot" against them to memorialize those who had died at Pearl Har- bor a year earlier.2 In Honolulu, the Advertiser editorial writer urged The ]journal of American-East Asian Relations, Vol. -

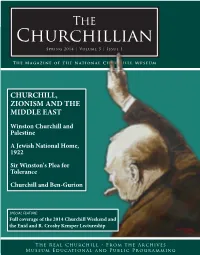

Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1

The Churchillian Spring 2014 | Volume 5 | Issue 1 The Magazine of the National Churchill Museum CHURCHILL, ZIONISM AND THE MIDDLE EAST Winston Churchill and Palestine A Jewish National Home, 1922 Sir Winston's Plea for Tolerance Churchill and Ben-Gurion SPECIAL FEATURE: Full coverage of the 2014 Churchill Weekend and the Enid and R. Crosby Kemper Lectureship The Real Churchill • From the Archives Museum Educational and Public Programming Board of Governors of the Association of Churchill Fellows FROM THE Jean-Paul Montupet MESSAGE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Chairman & Senior Fellow St. Louis, Missouri A.V. L. Brokaw, III Warm greetings from the campus of St. Louis, Missouri Westminster College. As I write, we are Robert L. DeFer still recovering from a wonderful Churchill th Weekend. Tis weekend, marking the 68 Earle H. Harbison, Jr. St. Louis, Missouri anniversary of Churchill’s visit here and his William C. Ives Sinews of Peace address, was a special one for Chapel Hill, North Carolina several reasons. Firstly, because of the threat R. Crosby Kemper, III of bad weather which, while unpleasant, Kansas City, Missouri never realized the forecast’s dismal potential Barbara D. Lewington and because of the presence of members of St. Louis, Missouri the Churchill family, Randolph, Catherine St. Louis, Missouri and Jennie Churchill for a frst ever visit. William R. Piper Tis, in tandem with a wonderful Enid St. Louis, Missouri PHOTO BY DAK DILLON and R. Crosby Kemper Lecture delivered by Paul Reid, defed the weather and entertained a bumper crowd of St. Louis, Missouri Churchillians at both dinner, in the Museum, and at a special ‘ask the experts’ brunch. -

British Responses to the Holocaust

Centre for Holocaust Education British responses to the Insert graphic here use this to Holocaust scale /size your chosen image. Delete after using. Resources RESOURCES 1: A3 COLOUR CARDS, SINGLE-SIDED SOURCE A: March 1939 © The Wiener Library Wiener The © AT FIRST SIGHT… Take a couple of minutes to look at the photograph. What can you see? You might want to think about: 1. Where was the photograph taken? Which country? 2. Who are the people in the photograph? What is their relationship to each other? 3. What is happening in the photograph? Try to back-up your ideas with some evidence from the photograph. Think about how you might answer ‘how can you tell?’ every time you make a statement from the image. SOURCE B: September 1939 ‘We and France are today, in fulfilment of our obligations, going to the aid of Poland, who is so bravely resisting this wicked and unprovoked attack on her people.’ © BBC Archives BBC © AT FIRST SIGHT… Take a couple of minutes to look at the photograph and the extract from the document. What can you see? You might want to think about: 1. The person speaking is British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. What is he saying, and why is he saying it at this time? 2. Does this support the belief that Britain declared war on Germany to save Jews from the Holocaust, or does it suggest other war aims? Try to back-up your ideas with some evidence from the photograph. Think about how you might answer ‘how can you tell?’ every time you make a statement from the sources. -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

79I /f NIGERIAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT AND PRESS FREEDOM, 1966-79 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Ehikioya Agboaye, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1984 Agboaye, Ehikioya, Nigerian Military Government and Press Freedom, 1966-79. Master of Arts (Journalism), May, 1984, 3 tables, 111 pp., bibliography, 148 titles. The problem of this thesis is to examine the military- press relationship inNigeria from 1966 to 1979 and to determine whether activities of the military government contributed to violation of press freedom by prior restraint, postpublication censorship and penalization. Newspaper and magazine articles related to this study were analyzed. Interviews with some journalists and mili- tary personnel were also conducted. Materials collected show that the military violated some aspects of press freedom, but in most cases, however, journalists were free to criticize government activities. The judiciary prevented the military from arbitrarily using its power against the press. The findings show that although the military occasionally attempted suppressing the press, there are few instances that prove that journalists were denied press freedom. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES............ .P Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Statement of the Problem Purpose of the Study Significant Questions Definition of Terms Review of the Literature Significance of the Study Limitations Methodology Organization II. PREMILITARY ERA,.... 1865-1966...18 . From Colonial to Indigenous Press The Press in the First Republic III. PRESS ACTIONS IN THE MILITARY'S EARLY YEARS 29 Before the Civil War The Nigeria-Biaf ran War and After IV. -

2Nd INFANTRY REGIMENT

2nd INFANTRY REGIMENT 1110 pages (approximate) Boxes 1243-1244 The 2nd Infantry Regiment was a component part of the 5th Infantry Division. This Division was activated in 1939 but did not enter combat until it landed on Utah Beach, Normandy, three days after D-Day. For the remainder of the war in Europe the Division participated in numerous operations and engagements of the Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe campaigns. The records of the 2nd Infantry Regiment consist mostly of after action reports and journals which provide detailed accounts of the operations of the Regiment from July 1944 to May 1945. The records also contain correspondence on the early history of the Regiment prior to World War II and to its training activities in the United States prior to entering combat. Of particular importance is a file on the work of the Regiment while serving on occupation duty in Iceland in 1942. CONTAINER LIST Box No. Folder Title 1243 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories January 1943-June 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories, July-October 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Histories, July 1944- December 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, July-September 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, October-December 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, January-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Casualty List, 1944-1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Journal, 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Narrative History, October 1944-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment History Correspondence, 1934-1936 2nd Infantry -

The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper

Article The Manchester Observer: biography of a radical newspaper Poole, Robert Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/28037/ Poole, Robert ORCID: 0000-0001-9613-6401 (2019) The Manchester Observer: biography of a radical newspaper. Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 95 (1). pp. 31-123. ISSN 2054-9318 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. http://dx.doi.org/10.7227/BJRL.95.1.3 For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk i i i i The Manchester Observer: Biography of a Radical Newspaper ROBERT POOLE, UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE Abstract The newly digitised Manchester Observer (1818–22) was England’s leading rad- ical newspaper at the time of the Peterloo meeting of August 1819, in which it played a central role. For a time it enjoyed the highest circulation of any provincial newspaper, holding a position comparable to that of the Chartist Northern Star twenty years later and pioneering dual publication in Manchester and London. -

The Battle of Britain Key Facts

The Battle of Britain Key Facts Read the key facts about the Battle of Britain. Cut them out and put them into chronological order on your timeline. You can decorate the timeline with your own drawings or real photographs that you find on the Internet. History | LKS2 | World War II | The Battle of Britain | Lesson 4 The Battle of Britain Key Facts The Battle of Britain Key Facts On 15th September 1940, the On 15th September 1940, the Germans launched another Germans launched another massive attack, but the British Mass bombing of airfields, massive attack, but the British fighters reacted quickly and it Mass bombing of airfields, harbours, radar stations and fighters reacted quickly and it became clear that the Germans harbours, radar stations and aircraft factories began on 13th became clear that the Germans could not win. This date is aircraft factories began on 13th August, 1940. could not win. This date is officially regarded as the end of August, 1940. officially regarded as the end of the Battle of Britain and this day the Battle of Britain and this day is commemorated each year. is commemorated each year. On 7th September 1940, the On 20th August 1940, the Prime On 7th September 1940, the On 20th August 1940, the Prime Germans moved onto bombing Minister Winston Churchill said: Germans moved onto bombing Minister Winston Churchill said: London as they believed enough 'Never in the field of human London as they believed enough 'Never in the field of human damage had been caused to conflict was so much owed by damage had been caused to conflict was so much owed by the RAF stations. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Does the Daily Paper Rule Britannia’:1 the British Press, British Public Opinion, and the End of Empire in Africa, 1957-60

The London School of Economics and Political Science ‘Does the Daily Paper rule Britannia’:1 The British press, British public opinion, and the end of empire in Africa, 1957-60 Rosalind Coffey A thesis submitted to the International History Department of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, August 2015 1 Taken from a reader’s letter to the Nyasaland Times, quoted in an article on 2 February 1960, front page (hereafter fp). All newspaper articles which follow were consulted at The British Library Newspaper Library. 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99, 969 words. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the role of British newspaper coverage of Africa in the process of decolonisation between 1957 and 1960. It considers events in the Gold Coast/Ghana, Kenya, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, South Africa, and the Belgian Congo/Congo. -

Publisher's Note

Adam Matthew Publications is an imprint of Adam Matthew Digital Ltd, Pelham House, London Road, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2AG, ENGLAND Telephone: +44 (1672) 511921 Fax: +44 (1672) 511663 Email: [email protected] POPULAR NEWSPAPERS DURING WORLD WAR II Parts 1 to 5: 1939-1945 (The Daily Express, The Mirror, The News of The World, The People and The Sunday Express) Publisher's Note This microfilm publication makes available complete runs the Daily Express, The Daily Mirror, the News of the World, The People, and the Sunday Express for the years 1939 through to 1945. The project is organised in five parts and covers the newspapers in chronological sequence. Part 1 provides full coverage for 1939; Part 2: 1940; Part 3: 1941; Part 4: 1942-1943; and finally, Part 5 covers 1944-1945. At last social historians and students of journalism can consult complete war-time runs of Britain’s popular newspapers in their libraries. Less august than the papers of record, it is these papers which reveal most about the impact of the war on the home front, the way in which people amused themselves in the face of adversity, and the way in which public morale was kept high through a mixture of propaganda and judicious reporting. Most importantly, it is through these papers that we can see how most ordinary people received news of the war. For, with a combined circulation of over 23 million by 1948, and a secondary readership far in excess of these figures, the News of the World, The People, the Daily Express, The Daily Mirror, and the Sunday Express reached into the homes of the majority of the British public and played a critical role in shaping public perceptions of the war.