Black Society Trilog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Literature in Japanese Film (1910-1938) Alex Pinar

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Kinotayo-2010

PROGRAMME - PROGRAMME - PROGRAMME - PROGRAMME - 20 Nov 11 Déc 2010 5eme FESTIVAL DU FILM JAPONAIS CONTEMPORAIN Mascotte de Kinotayo 2010 140 projectionsAvec la participation d'Écrans - d'asie 25 villes Kinotayo2010 Yoshi OIDA, l’Acteur flottant, président du Festival Kinotayo 2010 Pour le festival Kinotayo, c’est un immense honneur que d’avoir pour président ce comédien, acteur, metteur en scène et écrivain insaisissable, animé par l’omniprésente énergie de la vie, sur scène et en dehors. Yoshi Oida est un acteur hors du commun. Né à Kobe en 1933, il a dédié sa vie aux théâtres du monde entier, en ayant pour seule ligne de conduite de renoncer à la facilité. Son apprentissage commence au Japon : il est initié au théâtre Nô par les plus grands maîtres de l’école Okura. De cette expérience, il retirera l’importance de l’harmonie entre tous les éléments qui constituent l’outil principal du comédien : son corps. Puis en 1968 Yoshi Oida est invité à Paris par Jean-Louis Barrault pour travailler avec Peter Brook. Il fonde avec ce dernier le Centre International de Recherche Théâtrale (CIRT). Au contact du « magicien du théâtre européen », il apprend que le comédien doit être « un vent léger, qui devenant de plus en plus fort, doit allumer une flamme et la faire grandir ». Aux côtés du maître, il apprend également la mise en scène, métier qui l’occupe énormément aujourd’hui. Il sillonne alors le monde à la recherche de la maîtrise théâtrale la plus complète, apprenant les jeux Africains, Indien, Persan. Il s’interroge sur la frontière entre la scène et la vie de tous les jours : « Qu’ai-je appris sur la scène qui pourrait m’aider à vivre ma vie d’homme ordinaire ? ». -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 3, No. 2

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 3 . NUMBER 2 Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation I ANN THOMPSON Kagemusha and the Chushingura Motif JOSEPH S. CHANG Inspiring Images: The Influence of the Japanese Cinema on the Writings of Kazuo Ishiguro 39 GREGORY MASON Video Mom: Reflections on a Cultural Obsession 53 MARGARET MORSE Questions of Female Subjectivity, Patriarchy, and Family: Perceptions of Three Indian Women Film Directors 74 WIMAL DISSANAYAKE One Single Blend: A Conversation with Satyajit Ray SURANJAN GANGULY Hollywood and the Rise of Suburbia WILLIAM ROTHMAN JUNE 1989 The East- West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Kurosawa's Ran: Reception and Interpretation ANN THOMPSON AKIRA KUROSAWA'S Ran (literally, war, riot, or chaos) was chosen as the first film to be shown at the First Tokyo International Film Festival in June 1985, and it opened commercially in Japan to record-breaking busi ness the next day. The director did not attend the festivities associated with the premiere, however, and the reception given to the film by Japa nese critics and reporters, though positive, was described by a French critic who had been deeply involved in the project as having "something of the air of an official embalming" (Raison 1985, 9). -

¥PDF Programa De Ma 06.Fh9

Disseny: IMF DESCOMPTE DEL25%PERALS CLIENTSDECAIXACATALUNYA (El nombred’entradesambdescompte éslimitat) PROGRAMACIÓ * Les sessions que porten un asterisc compten amb la presència de part de l’equip artístic i/o tècnic. DIVENDRES 6 9.15h. Casino Prado. The Last Circus (curt) + Blood Tea and Red Strings (Anima’t) 11h. Casino Prado. Black Moon (Europa Imaginària) 11.15h. El Retiro. Seance (Orient Express – Casa Asia) 13h. El Retiro. Eye of the Spider (Orient Express – Kurosawa) 13.15h. Casino Prado. La Sabina (Europa Imaginària) 13.45h. Auditori. Ils (Secció Oficial Fantàstic) 15h. El Retiro. Taxidermia (Secció Oficial Fantàstic) 15h. Casino Prado. Ulisse (Europa Imaginària) 15.15h. Auditori. Broken (S.O.Méliès) 17h. El Retiro. Duelist (Orient Express – Casa Asia) * 17h. Casino Prado. Blue Velvet (Sitges Clàssics – Lynch) 18h. Auditori. Gala Inauguració Sitges 2006: For(r)est in the Des(s)ert (curt) + El Laberinto del Fauno * 19.15h. El Retiro. La Hora Fría (Secció Oficial Fantàstic) 19.15h. Casino Prado. Fantastic Voyage (Sitges Clàssics - Fleischer) 20.50h. Auditori. El Laberinto del Fauno (Passi privat Tel-Entrada Caixa Catalunya) 21.15h. El Retiro. Avida (S.O. Noves Visions) 21.15h. Casino Prado. The Last Circus (curt) + Blood Tea and Red Strings (Anima’t) 23h. Auditori. Ils (Secció Oficial Fantàstic) * 23h. El Retiro. The Pulse (Secció Oficial Première) 23h. Casino Prado. Soylent Green (Sitges Clàssics - Fleischer) 00.45h. Auditori. Broken (S.O. Méliès) 1h. El Retiro. Masters of Horror (I) (Midnight X-Treme) 1h. Casino Prado. Mondo Macabro (I): The Warrior + Devil’s Sword (Midnight X-Treme) DISSABTE 7 9h. El Retiro. Edmond (S.O. -

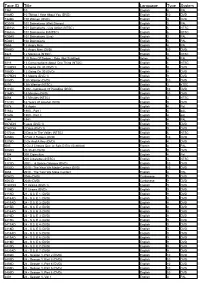

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

![Regard Sur Le Cinéma Japonais : La Jalousie Féminine… Au Féminin]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1057/regard-sur-le-cin%C3%A9ma-japonais-la-jalousie-f%C3%A9minine-au-f%C3%A9minin-251057.webp)

Regard Sur Le Cinéma Japonais : La Jalousie Féminine… Au Féminin]

Document generated on 09/29/2021 7:02 p.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Regard sur le cinéma japonais La jalousie féminine… au féminin Pascal Grenier Number 222, November–December 2002 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/48430ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Grenier, P. (2002). Review of [Regard sur le cinéma japonais : la jalousie féminine… au féminin]. Séquences, (222), 22–23. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2002 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ a dernière édition du Festival des films du monde rendait quittera femme et fille pour la retrouver. Non seulement veut-elle hommage au cinéma japonais avec la section Regard sur le passer beaucoup de temps avec lui mais aspire à leur union. L cinéma japonais. Il s'agissait de la troisième fois depuis les Lorsque que Hijiri s'immisce dans sa vie, elle se rend compte de la débuts du festival que le Japon était à l'honneur. Dès l'annonce de jalousie injustifiée éprouvée et renonce à sa relation avec Kouhei cette nouvelle, mon enthousiasme était sans borne compte tenu car ce dernier ne quittera jamais sa femme. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscrq>t has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in Qpewriter face, while others may be from aiQf type of computer printer. The qnaliQr of this reproduction is dependent upon the qnali^ of the copy snbmltted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard tnargins, and in^xroper alignment can adverse^ afiect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogrzq)hs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher qualiQr 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directfy to order. UMJ A Bell & Howell Informaiion Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 POLITICS AND THE NOVEL; A STUDY OF LIANG CH'I-CITAO'S THE FUTURE OF NEW CHINA AND HIS VIEWS ON FICTION DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Chun-chi Chen, B.A., M.A. -

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Horaire Films

DESHORAIRE FILMS FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DE FILMS · 25 e ÉDITION 5-25 AOÛT 2021 FESTIVAL EN LIGNE ET EN SALLE www.fantasiafestival.com DISPONIBLE EN LIGNE À TRAVERS LE CANADA Illustration : Donald Caron Ça comprend des films qui vous suivent partout. APPLI HELIX TV Certaines conditions s’appliquent. IPTV-FANTASIA-REQUIN-10.5X14.125-2107 Document: IPTV-FANTASIA-REQUIN-10.5X14.125-2107 Échelle: 25% Format: 10.5 po X 14.125 po DPI final: 100 dpi ÉPREUVE Coordo: Anouk Chollet Bleed: 0.04 po Imprimeur: Safety: 0.3 po 01 COULEUR PAPIER FOND CMYK RGB Couché Retro Enr Montage: 9 juillet PANTONE Mat Jrnl Final: par: VGAUD ACT OF VIOLENCE IN A AGNES #BLUE_WHALE THE 12 DAY TALE OF THE YOUNG JOURNALIST ÉTATS-UNIS | USA Réal/Dir: Mickey Reece RUSSIE | RUSSIA Réal/Dir: Anna Zaytseva MONSTER THAT DIED IN 8 URUGUAY | URUGUAY Réal/Dir: Manuel Lamas PREMIÈRE INTERNATIONALE | INTERNATIONAL PREMIERE PREMIÈRE MONDIALE | WORLD PREMIERE JAPON | JAPAN Réal/Dir: Shunji Iwai PREMIÈRE NORD-AMÉRICAINE | NORTH AMERICAN PREMIERE Avec son style romantique et maximaliste, Un déchirant et anxiogène thriller russe en PREMIÈRE NORD-AMÉRICAINE | NORTH AMERICAN PREMIERE Blanca, une brillante jeune journaliste qui Mickey Reece nous amène dans un couvent Screenlife qui explore un défi sur les médias Le plus récent film de Shunji Iwai est une rédige une thèse sur la violence, ignore qu’un aux prises avec des rumeurs de possession sociaux menant à une vague de suicides. savoureuse tranche de vie pandémique méta tueur psychopathe est sur ses traces. démoniaque. Gut-wrenching dread tears through this tense entremêlant isolement et kaiju! Blanca, a brilliant young journalist who is writing a With his signature romantic maximalism, Mickey Russian Screenlife thriller that explores a grisly Shunji Iwai’s latest is a delightfully meta slice of thesis on violence, is unaware that a psychopathic Reece’s latest draws us into a convent gripped by social media suicide challenge. -

Shadowrun: Hong Kong

SHADOWRUN HONG KONG MEL ODOM BASED ON A STORY BY HAREBRAINED SCHEMES PROLOGUE RAYMOND BLACK The Redmond Barrens Seattle United Canadian and American States 2044 I’ll never forget the night I met Raymond Black, mostly because I’d believed Duncan was going to die and leave me all alone. Raymond Black changed that. He changed a lot of things. Me and Duncan, we’d been alone for a long time. I was a couple years older than him, so I could remember back farther than he could, but every time I did, all I could recall were the foster homes I got bounced out of regularly. The longest I’d ever stayed in one was with the Croydon family for two years. They taught me how to pick pockets, hotwire a car, fight with a blade, and pick a lock. When I turned thirteen, I used those skills to get away from them and escape into the shadows. A few months after that, I found Duncan Wu living on dumpster food in an alley. He hadn’t run away from his foster home to find something better. He’d run for his life. His foster parents had set up a deal to sell him and the three other kids to a sex slave ring. He was the only one who’d gotten away. Part of me wanted to leave him there, but I couldn’t because I knew from the shape he was in, starving and covered in sores, he wouldn’t make it on his own. So I’d taken him with me, fed him, sheltered him, and gotten him as healthy as we could be under the circumstances. -

ALSO LIKE LIFE: the FILMS of HOU HSIAO-HSIEN New Addition: Hou Hsiao-Hsien in Conversation at BFI Southbank – Monday 14 September

ALSO LIKE LIFE: THE FILMS OF HOU HSIAO-HSIEN New addition: Hou Hsiao-Hsien In Conversation at BFI Southbank – Monday 14 September Thursday 13 August 2015, London The BFI is delighted to announce that one of the leading figures of the Taiwanese New Wave Hou Hsiao-Hsien, whose latest film The Assassin won Best Director at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, will make a very rare visit to the UK to take part in an In Conversation event at BFI Southbank. The event, which takes place on Monday 14 September, is part of Also Life Life: The Films of Hou Hsiao- Hsien, a major retrospective celebrating Hou’s work, which takes place from 2 Sept – 6 Oct 2015 at BFI Southbank. Hou-Hsiao-Hsien has helped put Taiwanese cinema on the international map with work that explores the island’s rapidly changing present as well as its turbulent, often bloody past, and is one of the best examples in world cinema of a director who found his own distinctive style and voice while working on the job. The season will kick off with Cute Girl (1980), Cheerful Wind (1981) and The Green Green Grass of Home (1982), all starring Hong Kong pop star Kenny Bee; these early films offer a mixture of comedy and romance and begin to show Hou’s interest in Taiwan’s regional differences, a key theme of his later films. Hou’s other early films such as The Sandwich Man (1983) and The Boys from Fengkuei (1983) dramatised engaging life stories – including his own in The Time to Live and the Time to Die (1985).