Nineteen Eighty-Four

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marcelo Pelissioli from Allegory Into Symbol: Revisiting George Orwell's Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four in the Light Of

MARCELO PELISSIOLI FROM ALLEGORY INTO SYMBOL: REVISITING GEORGE ORWELL’S ANIMAL FARM AND NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR IN THE LIGHT OF 21 ST CENTURY VIEWS OF TOTALITARIANISM PORTO ALEGRE 2008 2 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS ÊNFASE: LITERATURAS DE LÍNGUA INGLESA LINHA DE PESQUISA: LITERATURA, IMAGINÁRIO E HISTÓRIA FROM ALLEGORY INTO SYMBOL: REVISITING GEORGE ORWELL’S ANIMAL FARM AND NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR IN THE LIGHT OF 21 ST CENTURY VIEWS OF TOTALITARIANISM MESTRANDO: PROF. MARCELO PELISSIOLI ORIENTADORA: PROFª. DRª. SANDRA SIRANGELO MAGGIO PORTO ALEGRE 2008 3 4 PELISSIOLI, Marcelo FROM ALLEGORY INTO SYMBOL: REVISITING GEORGE ORWELL’S ANIMAL FARM AND NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR IN THE LIGHT OF 21 ST CENTURY VIEWS OF TOTALITARIANISM Marcelo Pelissioli Porto Alegre: UFRGS, Instituto de Letras, 2008. 112 p. Dissertação (Mestrado - Programa de Pós-graduação em Letras) Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. 1.Totalitarismo, 2.Animal Farm, 3. Nineteen Eighty-Four, 4. Alegoria, 5. Símbolo. 5 Acknowledgements To my dear professor and adviser Dr. Sandra Maggio, for the intellectual and motivational support; To professors Jane Brodbeck, Valéria Salomon, Vicente Saldanha, Paulo Ramos, Miriam Jardim, José Édil and Edgar Kirchof, professors who guided me to follow the way of Literature; To my bosses Antonio Daltro Costa, Gerson Costa and Mary Sieben, for their cooperation and understanding; To my friends Anderson Correa, Bruno Albo Amedei and Fernando Muniz, for their sense of companionship; To my family, especially my mother and grandmother, who always believed in my capacity; To my wife Ana Paula, who has always stayed by my side along these long years of study that culminate in the handing of this thesis; And, finally, to God, who has proved to me along the years that He really is the God of the brave. -

The Cultural Cold War the CIA and the World of Arts and Letters

The Cultural Cold War The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters FRANCES STONOR SAUNDERS by Frances Stonor Saunders Originally published in the United Kingdom under the title Who Paid the Piper? by Granta Publications, 1999 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2000 Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press oper- ates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in in- novative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450 West 41st Street, 6th floor. New York, NY 10036 www.thenewpres.com Printed in the United States of America ‘What fate or fortune led Thee down into this place, ere thy last day? Who is it that thy steps hath piloted?’ ‘Above there in the clear world on my way,’ I answered him, ‘lost in a vale of gloom, Before my age was full, I went astray.’ Dante’s Inferno, Canto XV I know that’s a secret, for it’s whispered everywhere. William Congreve, Love for Love Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................... v Introduction ....................................................................1 1 Exquisite Corpse ...........................................................5 2 Destiny’s Elect .............................................................20 3 Marxists at -

Professor Peter Davison

GETTING IT RIGHT – Peter Davison January - March 2010 GETTING IT RIGHT January – March 2010 Peter Davison On at least two occasions George Orwell said he had done his best to be honest in his writings. In a letter to Dwight Macdonald on 26 May 1943 he wrote, „Within my own framework I have tried to be truthful‟; in a „London Letter‟ to Partisan Review, probably written in October 1944, he said, „I have tried to tell the truth‟ and goes on to devote the whole Letter to where in past Letters he had „got it wrong and why‟. When giving titles to volumes X to XX of The Complete Works, „I have tried to tell the truth‟ seemed to me apposite for one of them (Volume XVI). Telling the truth went further for Orwell. Writing about James Burnham, he was aware that what he had written in his „Second Thoughts on James Burnham‟ in Polemic, 3 (XVIII, pp. 268-84) would not be liked by that author; „however,‟ he wrote, „it is what I think‟ (XVIII, p. 232). Attempting to „get it right‟, even in the much lowlier task of editing than in the great variety of activities in which Orwell engaged, is about the only thing I can claim to have in common with Orwell. I am aware and embarrassed by my multitude of mistakes, misunderstandings, and my sheer ignorance. The Lost Orwell does what it can to try, belatedly, „to get it right‟. I was once taken to task by a reader who complained that „typewritten‟ had been misspelt: how ironic he thought! Would that were all! What one might call „ordinary, run-of-the-mill, errors‟ are no more than a matter of paying sustained attention – although maintaining that over some 8,500 pages of The Complete Works and seventeen years, with many changes of publisher, is clearly difficult. -

George Orwell: the Critical Heritage

GEORGE ORWELL: THE CRITICAL HERITAGE THE CRITICAL HERITAGE SERIES General Editor: B.C.Southam The Critical Heritage series collects together a large body of criticism on major figures in literature. Each volume presents the contemporary responses to a particular writer, enabling the student to follow the formation of critical attitudes to the writer’s work and its place within a literary tradition. The carefully selected sources range from landmark essays in the history of criticism to fragments of contemporary opinion and little published documentary material, such as letters and diaries. Significant pieces of criticism from later periods are also included in order to demonstrate fluctuations in reputation following the writer’s death. GEORGE ORWELL THE CRITICAL HERITAGE Edited by JEFFREY MEYERS London and New York First published in 1975 Reprinted in 1997 by Routledge This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE & 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 Compilation, introduction, notes and index © 1975 Jeffrey Meyers All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0–415–15923–7 (Print Edition) ISBN 0–203–19635–X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0–203–19638–4 (Glassbook Format) For Alfredo and Barbara General Editor’s Preface The reception given to a writer by his contemporaries and near- contemporaries is evidence of considerable value to the student of literature. -

Forbidden to Dream Again: Orwell and Nostalgia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Forbidden To Dream Again: Orwell and Nostalgia Joseph Brooker There is even a tendency to talk nostalgically of the days of the V1. The good old doodlebug did at least give you time to get under the table, etc. etc. Whereas, in fact, when the doodlebugs were actually dropping, the usual subject of complaint was the uncomfortable waiting period before they went off. Some people are never satisfied. ‘As I Please’, 1 December 1944 (CEJL 3: 320) The Orwell century closed as the anniversary of his birth was marked in 2003. As it recedes, it is appropriate to think about the forms taken by retrospect. Andreas Huyssen has argued that contemporary culture is pervaded by commemoration. Memory, private or public, has been a theoretical focus and a political battlefield, in an era of controversial monuments and ‘memory wars’.1 In what Roger Luckhurst has dubbed the Traumaculture of recent years, the relation of individuals and groups to the past has often been staged as grieving and self-lacerating.2 But the flipside of the traumatic paradigm of memory has gone comparatively unexplored, despite its own weight in contemporary society. Nostalgia is vital to the appeal of the retro culture of the last twenty years, in cinema, literature and other arts.3 It remains politically contentious: regularly involved, and often used as an accusation, in arguments over Englishness, social change, national decline. Yet the topic has yet to receive the attention accorded to darker forms of memory.4 This essay aims to enhance our thinking about it via a reading of George Orwell. -

A Remembrance of George Orwell (1974), P

Notes Introduction 1. Jacintha Buddicom, Eric and Us: A Remembrance of George Orwell (1974), p. 11. Hereafter as Eric and Us. 2. See Tables 2.1 and 5.1, pp. 32 and 92-3, and, for full details, my 'Orwell: Balancing the Books', The Library, VI, 16 (1994), 77-100. 1 Getting Started 1. Sir Richard Rees, George Orwell: Fugitive from the Camp of Victory (1961), pp. 144-5. Hereafter as 'Rees'. Mabel Fierz's report is quoted by Shelden, p. 127. 2. Eric and Us, pp. 13-14. 3. CEJL, iv.412. 4. Rees, p. 145. 5. See Bernard Crick, George Orwell: A Life, (third, Penguin, edition, 1992), p. 107; Michael Shelden, Orwell: The Authorised Biography (1991), p. 73; US pagination differs. Hereafter as 'Crick' and 'Shelden' respectively. 6. Stephen Wadhams, Remembering Orwell (1984), p. 44. As 'Wadhams' hereafter. Wadhams's interviews, conducted in 1983, are a particu larly valuable source of information. 7. Rees, p. 145. Mabel Fierz gave Wadhams a similar account, pp. 44-5. 8. Crick, pp. 48-9; Shelden, pp. 22-3. 9. VII.37. See also Crick, pp. 54-5; he identifies Kate of the novel with Elsie of the Anglican Convent Orwell attended from 1908 to 1911, with whom Orwell says in 'Such, Such Were the Joys' he 'fell deeply in love' - when aged about 6. 10. Eric and Us, p. 19. A footnote on that page reproduces part of a letter from Avril to Jacintha, 14 March 1973, in which Avril, having read a draft of Jacintha's book, says that she 'is making a very fair assess ment of Eric's boyhood'. -

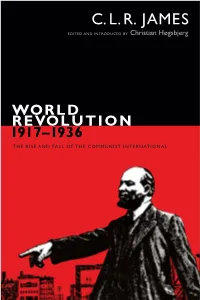

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED and INTRODUCED by Christian Høgsbjerg

C. L. R. JAMES EDITED AND INTRODUCED BY Christian Høgsbjerg WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 THE RISE AND FALL OF THE COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 ||||| C. L. R. James in Trafalgar Square (1935). Courtesy of Getty Images. the c. l. r. james archives recovers and reproduces for a con temporary audience the works of one of the great intel- lectual figures of the twentiethc entury, in all their rich texture, and will pres ent, over and above historical works, new and current scholarly explorations of James’s oeuvre. Robert A. Hill, Series Editor WORLD REVOLUTION 1917–1936 The Rise and Fall of the Communist International ||||| C. L. R. J A M E S Edited and Introduced by Christian Høgsbjerg duke university press Durham and London 2017 Introduction and Editor’s Note © 2017 Duke University Press World Revolution, 1917–1936 © 1937 C. L. R. James Estate Harry N. Howard, “World Revolution,” Annals of the American Acad emy of Po liti cal and Social Science, pp. xii, 429 © 1937 Pioneer Publishers E. H. Carr, “World Revolution,” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1931–1939) 16, no. 5 (September 1937), 819–20 © 1937 Wiley All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Typeset in Arno Pro and Gill Sans Std by Westchester Publishing Ser vices Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: James, C. L. R. (Cyril Lionel Robert), 1901–1989, author. | Høgsbjerg, Christian, editor. Title: World revolution, 1917–1936 : the rise and fall of the Communist International / C. L. R. James ; edited and with an introduction by Christian Høgsbjerg. -

Introduction

Introduction December 1948. A man sits at a typewriter, in bed, on a remote island, fighting to complete the book that means more to him than any other. He is terribly ill. The book will be finished and, a year or so later, so will the man. January 2017. Another man stands before a crowd, which is not as large as he would like, in Washington, DC, taking the oath of office as the forty-fifth president of the United States of America. His press secretary later says that it was the “largest audience to ever witness an inauguration—period—both in person and around the globe.” Asked to justify such a preposterous lie, the president’s adviser describes the statement as “alternative facts.” Over the next four days, US sales of the dead man’s book will rocket by almost 10,000 percent, making it a number-one best seller. When George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four was published in the United Kingdom on June 8, 1949, in the heart of the twentieth century, one critic wondered how such a timely book could possibly exert the same power over generations to come. Thirty-five years later, when the present caught up with Orwell’s future and the world was not the nightmare he had described, commentators again predicted that the book’s popularity would wane. Another thirty-five years have elapsed since then, and Nineteen Eighty-Four remains the book we turn to when truth is mutilated, language is distorted, power is abused, and we want to know how bad things can get, because someone who lived and died in another era was clear-sighted enough to identify these evils and sufficiently talented to present them in the form of a novel that Anthony Burgess, author of A Clockwork Orange, called “an apocalyptical codex of our worst fears.” xiv Introduction Nineteen Eighty-Four has not just sold tens of millions of copies; it has infiltrated the consciousness of countless people who have never read it. -

A Political Writer

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85842-7 - The Cambridge Companion to George Orwell Edited by John Rodden Excerpt More information 1 JOHN ROSSI AND JOHN RODDEN A political writer George Orwell was primarily a political writer. In his essay ‘Why I Write’ (1946), Orwell stated he wanted ‘to make political writing into an art’. While he produced four novels between the years 1933 and 1939, it was clear that his real talent did not lie in traditional fiction. He seems instinctively to have understood that the documentary style he developed in his essays and his semi-autobiographical monograph, Down and Out in Paris and London (1932), was unsuitable to the novel format. Ultimately, the reason for this is simple – what profoundly interested Orwell were political questions. His approach to politics evolved during the decade of the 1930s along with his own idiosyncratic journey from English radical to his unique, eccentric form of socialism. Orwell claimed he had an unhappy youth. If one believes the memories of those like his neighbour Jacintha Buddicom, who knew him as a carefree, fun loving young boy, Orwell’s claim of unhappiness seems exaggerated. In his essay ‘Such, Such Were the Joys’, he portrays his school, St Cyprian’s, as an unpleasant amalgam of snobbery, bullying and petty acts of tyranny. The truth lies somewhere between these two extremes, something Orwell himself understood. ‘Whoever writes about his childhood must beware exaggeration and self-pity’, he wrote of his years at St Cyprian’s. Orwell’s experiences at Eton were more positive. Although he failed to distinguish himself academically, he received a solid education, one that he drew on for the rest of his life. -

Bloom's Literature How to Write About Nineteen Eighty Four Reading to Write

Bloom's Literature How to Write about Nineteen Eighty Four Reading to Write Published in 1949, Orwell's classic dystopian novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four (or 1984 as it is often published now), has become so well known as to have provided a sort of shorthand for critiques of overly intrusive and heavy-handed government. One need only to apply the epithet of "Big Brother" to a government or organization in order to conjure up the nightmarish oppression so vividly portrayed in Orwell's most famous novel. 1984 depicts a fictional society ruled by an oppressive regime that functions mainly to ensure and to increase its own power and status. To this end, Big Brother demands complete obedience and allows its subjects very little in the way of personal freedom of action or expression. Not for lack of considerable effort, the government has been unsuccessful in wiping out all thoughts of rebellion. Protagonist Winston Smith marshals the courage to engage in a small act that is considered a terrible crime by the party: recording his own thoughts in a private diary. Winston's journal reveals a great deal about the society in which he lives and about his own inner workings as well. Have a look at the scene that describes Winston making an entry in his journal: He was a lonely ghost uttering a truth nobody would ever hear. But so long as he uttered it, in some obscure way the continuity was not broken. It was not by making yourself heard but by staying sane that you carried on the human heritage. -

The Cambridge Companion to George Orwell Edited by John Rodden Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85842-7 - The Cambridge Companion to George Orwell Edited by John Rodden Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to george orwell George Orwell is regarded as the greatest political writer in English of the twen- tieth century. The massive critical literature on Orwell has not only become extremely specialised, and therefore somewhat inaccessible to the non-scholar, but it has also contributed to and even created misconceptions about the man, the writer, and his literary legacy. For these reasons, an overview of Orwell’s writing and influence is an indispensable resource. Accordingly, this Companion serves as both an introduction to Orwell’s work and furnishes numerous innovative interpretations and fresh critical perspectives on it. Throughout the Companion, which includes chapters dedicated to Orwell’s major novels, Nineteen Eighty- Four and Animal Farm, Orwell’s work is placed within the context of the political and social climate of the time. His response to the Depression, British imperi- alism, Stalinism, the Second World War, and the politics of the British Left are all examined. Chapters also discuss Orwell’s status among intellectuals and in the literary academy, and a detailed chronology of Orwell’s life and work is included. John Rodden has taught at the University of Virginia and the University of Texas at Austin. He has authored or edited several books on George Orwell, including The Politics of Literary Reputation: the Making and Claiming of ‘St George’ Orwell (1989), Understanding Animal Farm in Historical Con- text (1999), Scenes from an Afterlife: the Legacy of George Orwell (2003), George Orwell Into the Twenty-First Century (2004), and Every Intellectual’s Big Brother: George Orwell’s Literary Siblings (2006). -

Dulley, Paul Richard.Pdf

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details ‘In Front of your Nose’: The Existentialism of George Orwell Paul Richard Dulley PhD In Literature and Philosophy University of Sussex April 2015 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be submitted, whole or in part, to another university for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………............... 1 University of Sussex Paul Richard Dulley PhD in Literature and Philosophy ‘In Front of your Nose’: The Existentialism of George Orwell Summary George Orwell’s reputation as a writer rests largely upon his final two works, selected essays and some of his journalism. As a novelist, he is often considered limited, and it is for this reason that his writing has perhaps received less serious attention than that of many of his contemporaries. Some recent publications have sought to redress this balance, identifying an impressive level of artistry, not only in his more recognised works, but in the neglected novels of the 1930s.