Alaris Capture Pro Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England

ABSTRACT “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided by Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England Laura Christine Oliver, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D. This thesis argues that while patriarchy was certainly present in England during the late medieval period, women of the middle and upper classes were able to exercise agency to a certain degree through using both the patriarchal bargain and an economy of makeshifts. While the methods used by women differed due to the resources available to them, the agency afforded women by the patriarchal bargain and economy of makeshifts was not limited to the aristocracy. Using Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe as cases studies, this thesis examines how these women exercised at least a limited form of agency. Additionally, this thesis examines whether ordinary women have access to the same agency as elite women. Although both were exceptional women during this period, they still serve as ideal case studies because of the sources available about them and their status as role models among their contemporaries. “She Should Have More if She Were Ruled and Guided By Them”: Elizabeth Woodville and Margery Kempe, Female Agency in Late Medieval England by Laura Christine Oliver, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Beth Allison Barr, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Julie A. -

How Did Lambert Simnel Challenge Henry VII's Reign?

How did Lambert Simnel challenge Henry VII’s reign? L/O : TO EXPLAIN WHY THE REBELS USED SIMNEL IN THE CAMPAIGN CHALLENGE 1 : A S S E S S THE THREAT TO HENRY’S REIGN CHALLENGE 2 : A N A L Y S E THE SIGNIFICANCE OF FOREIGN INVOLVEMENT K E Y W O R D S : PRETENDER AND MERCENARIES First task-catch up on the background reading… https://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/tudor- england/the-lambert-simnel-rebellion/ When you find someone you have not heard of, please take 5 minutes to Google them and jot down a few notes. Starting point… Helpful tip: Before you start to race through this slide, make sure that you know something about the Battle of Bosworth, the differences between Yorkists and Lancastrians and the story behind the Princes in the Tower. In the meantime - were the ‘Princes in the Tower’ still alive? Richard III and Henry VII both had the problem of these princely ‘threats’ but if they were dead who would be the next threat? Possibly, Edward, Earl of Warwick who had a claim to the throne What is a ‘pretender’ ? Royal descendant those throne is claimed and occupied by a rival, or has been abolished entirely. OR …an individual who impersonates an heir to the throne. The Role of Oxford priest Symonds was Lambert Simnel’s tutor Richard Symonds Yorkist Symonds thought Simnel looked like one of the Princes in the Tower Plotted to use him as a focus for rebellion – tutored him in ‘princely skills’ Instead, he changed his mind and decided to use him as an Earl of Warwick look-a-like Margaret, Duchess of Burgundy Sister of Edward IV and Richard -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

Richard III and Ireland GWEN WATERS ‘Richard, by the Grace of God, King of England and France, Lord of Ireland.’ WITH THE CROWN OF ENGLAND,Richard III acquired also the lordship of Ireland and set about attending to matters Irish with his customary despatch. He sent ‘his trusty welbeloved Maister William Lacy . unto his said lande of Irland’ with letters to the Council in general and to individual members of it, Lacy being instructed to show that the King ‘after the stablisshing of this his Realme of England principally afore othere thinges entendethe for the wele of this lands of Irland to set and advise suche good Rule and politique guyding there as any of his noble progenitors . .’.' He was taking on no easy task. As lords of Ireland, the Plantagenet kings had been fulfilling this role with varying lack of success since Adrian IV, the only English Pope, had given Henry II a mandate to over-run the neighbouring country and reform ‘the evil customs of the Irish people.” When Prince John, made ‘Lord of Ireland' by his father, ascended the throne, the dominion became linked with English sovereignty but the monarch was not termed ‘King of Ireland’ until Henry VIII so designated himself. Among the barons who accompanied John to Ireland and, like land- pirates, carved out territories for themselves, was William de Burgo who, despite being one of the conquering race, seems to have established himself successfully among the native people and, in 1193, married an Irish princess, the daughter of Donal Mor O'Brien, King of Thomond. -

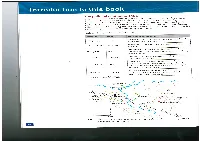

5 Tudor Textbook for GCSE to a Level Transition

Introduction to this book The political context in 1485 England had experienced much political instability in the fifteenth century. The successful short reign of Henry V (1413-22) was followed by the disastrous rule of Henry VI. The shortcomings of his rule culminated in the s outbreak of the so-called Wars of the Roses in 1455 between the royal houses of Lancaster and York. England was then subjected to intermittent civil war for over thirty years and five violent changes of monarch. Table 1 Changes of monarch, 1422-85 Monarch* Reign The ending of the reign •S®^^^^^3^^!6y^':: -; Defeated in battle and overthrown by Edward, Earl of Henry VI(L] 1422-61 March who took the throne. s Overthrown by Warwick 'the Kingmaker' and forced 1461-70 Edward IV [Y] into exile. Murdered after the defeat of his forces in the Battle of Henry VI [L] 1470-?! Tewkesbury. His son and heir, Edward Prince of Wales, was also killed. Died suddenly and unexpectedly, leaving as his heir 1471-83 Edward IV [Y] the 13-year-old Edward V. Disappeared in the Tower of London and probably murdered, along with his brother Richard, on the orders of Edward V(Y] 1483 his uncle and protector, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who succeeded him on the throne. Defeated and killed at the Battle of Bosworth. Richard III [Y] 1483-85 Succeeded on the throne by his successful adversary Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond. •t *(L]= Lancaster [Y)= York / Sence Brook RICHARD King Dick's Hole ao^_ 00/ g •%°^ '"^. 6'^ Atterton '°»•„>••0' 4<^ Bloody. -

AN Tacht UM ATHCHÓIRIÚ an DLÍ REACHTÚIL 2007

———————— Uimhir 28 de 2007 ———————— AN tACHT UM ATHCHÓIRIÚ AN DLÍ REACHTÚIL 2007 [An tiontú oifigiúil] ———————— RIAR NA nALT Alt 1. Mínithe. 2. Athchóiriú an dlí reachtúil i gcoitinne, aisghairm agus cosaint. 3. Aisghairm shonrach. 4. Gearrtheidil a shannadh. 5. Leasú ar an Short Titles Act 1896. 6. Leasú ar an Acht um Ghearrtheidil 1962. 7. Leasuithe ilghnéitheacha ar ghearrtheidil iar-1800. 8. Fianaise ar sheanreachtanna áirithe, etc. 9. Cosaint. 10. Gearrtheideal agus comhlua. SCEIDEAL 1 Reachtanna a Choimeádtar CUID 1 Reachtanna Éireannacha Réamh-Aontachta 1169 go 1800 CUID 2 Reachtanna Shasana 1066 go 1706 CUID 3 Reachtanna na Breataine Móire 1707 go 1800 CUID 4 Reachtanna Ríocht Aontaithe na Breataine Móire agus na hÉireann 1801 go 1922 1 [Uimh. 28.]An tAcht um Athchóiriú an Dlí [2007.] Reachtúil 2007. SCEIDEAL 2 Reachtanna a Aisghairtear go Sonrach CUID 1 Reachtanna Éireannacha Réamh-Aontachta 1169 go 1800 CUID 2 Reachtanna Shasana 1066 go 1706 CUID 3 Reachtanna na Breataine Móire 1707 go 1800 CUID 4 Reachtanna Ríocht Aontaithe na Breataine Móire agus na hÉireann 1801 go 1922 ———————— 2 [2007.]An tAcht um Athchóiriú an Dlí [Uimh. 28.] Reachtúil 2007. Na hAchtanna dá dTagraítear Bill of Rights 1688 1 Will. & Mary, Sess. 2. c.2 Documentary Evidence Act 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. 37 Documentary Evidence Act 1882 45 & 46 Vict., c. 9 Dower Act, 1297 25 Edw. 1, Magna Carta, c. 7 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) (No. 2) 1867 31 & 32 Vict., c. 3 Dublin Hospitals Regulation Act 1856 19 & 20 Vict., c. 110 Evidence Act 1845 8 & 9 Vict., c. -

Perkin Warbeck (NZ Version)

Whether my hero was or was not an impostor, he was 1 believed to be the true man by his contemporaries . Perkin Warbeck Talk to the Australasian Convention of the Richard III Society, Upper Hutt, New Zealand, 13 - 15 April 2007 Dorothea Preis The young man, called by Henry VII's spin doctors, "Perkin Warbeck", has been surrounded by controversy ever since he first appeared on the world stage. He claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, the younger son of Edward IV, and thus would have been the brother of Henry's Queen Elizabeth. As Perkin Warbeck he is often regarded by historians as a footnote of little consequence to the glorious Tudor reign, and this is certainly the image that the Tudors liked to create. As we shall see, whatever Henry’s efforts at portraying the affair, this young man had him seriously worried and was widely accepted as Richard of York. As we know according to Tudor history Richard III was that evil monster who killed his poor innocent nephews. Therefore anyone claiming to be one of these nephews had to be an impostor, and a rather stupid one at that. However, there is no proof that they were indeed murdered by their uncle, or anyone else for that matter, and once we acknowledge this, we can have a more unbiased look at this young man’s identity. When Henry came to the throne he had the Titulus Regius, stating that Edward IV's children were illegitimate, revoked, in order to have an added claim to the throne through his wife. -

Usurpation, Propaganda and State-Influenced History in Fifteenth-Century England

"Winning the People's Voice": Usurpation, Propaganda and State-influenced History in Fifteenth-Century England. By Andrew Broertjes, B.A (Hons) This thesis is presented for the Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia Humanities History 2006 Table of Contents Abstract Acknowledgements Introduction p. 1 Chapter One: Political Preconditions: Pretenders, Usurpation and International Relations 1398-1509. p. 19 Chapter Two: "The People", Parliament and Public Revolt: the Construction of the Domestic Audience. p. 63 Chapter Three: Kingship, Good Government and Nationalism: Contemporary Attitudes and Beliefs. p. 88 Chapter Four: Justifying Usurpation: Propaganda and Claiming the Throne. p. 117 Chapter Five: Promoting Kingship: State Propaganda and Royal Policy. p. 146 Chapter Six: A Public Relations War? Propaganda and Counter-Propaganda 1400-1509 p. 188 Chapter Seven: Propagandistic Messages: Themes and Critiques. p. 222 Chapter Eight: Rewriting the Fifteenth Century: English Kings and State Influenced History. p. 244 Conclusion p. 298 Bibliography p. 303 Acknowledgements The task of writing a doctoral thesis can be at times overwhelming. The present work would not be possible without the support and assistance of the following people. Firstly, to my primary supervisor, Professor Philippa Maddern, whose erudite commentary, willingness to listen and general support since my undergraduate days has been both welcome and beneficial to my intellectual growth. Also to my secondary supervisor, Associate Professor Ernie Jones, whose willingness to read and comment on vast quantities of work in such a short space of time has been an amazing assistance to the writing of this thesis. Thanks are also owed to my reading group, and their incisive commentary on various chapters. -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

Coins Attributed to the Yorkist Pretenders, 1487-1498 JOHN ASHDOWN-HILL Since the issue of coins is a normal concomitant of sovereignty, aspiring rulers often make a point of issuing at least a token coinage. Thus, in the aftermath of 1688 James VII and II, deprived of all his thrones by his daughter and son- in-law, continued to iésue coins in Ireland. Having no bullion at his disposal, he was reduced to producing ‘gun money’.‘ In 1708 dies were prepared for James II’s son, the ‘Old Pretender’, who planned a very beautiful silver crown coin bearing his royal title as KingJames III.2 In the nineteenth century medallic ‘coins’, which never circulated as currency, but were merely passed amongst their faithful adherents as mementos, were issued in the names of the dethroned legitimist Bourbonking ‘Hemi V’ of France, and of the Carlist pretenders to the Spanish throne. It is asserted that coins were likewise issued on behalf of the Yorkist pretenders of Henry VII’s reign, and these alleged Yorkist pieces are the subject of the present study. Although it is convenient to group the putative Yorkist specimens under the generic term ‘coins’, in fact not all of them are true coins. One alleged specimen is a jetton,3 while another appears to have been a commemorative or medallic issue, rather like those of Henri V and the Carlists. Various studies relating to the ‘coins’of the Yorkist pretenders have been published during the past 150 years. These were written by and for numismatists. 4 They concentrate on the nurnismatic evidence and make little attempt to evaluate the historical sources relating to the pretenders and their 1Coins madefromgun metal. -

Lambert Simnel and the King from Dublin

Lambert Simnel and the King from Dublin GORDON SMITH Throughout his reign (1485-1509) Richard III's supplanter Henry VII was troubled by pretenders to his throne, the most important of whom were Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck.1 Both are popularly remembered perhaps because their names have a pantomime sound to them, and a pantomime context seems a suitable one for characters whom Henry accused of being not real pretenders but mere impersonators. Nevertheless, there have been some doubts about the imposture of Perkin, although there appear to have been none before now about Lambert.2 As A.F. Pollard observed, 'no serious historian has doubted that Lambert was an impostor'.3 This observation is supported by the seemingly straightforward traditional story about the impostor Lambert Simnel, who was crowned king in Dublin but defeated at the battle of Stoke in 1487, and pardoned by Henry VII. This story can be recognised in Francis Bacon's influential history of Henry's reign, published in 1622, where Lambert first impersonated Richard, Duke of York, the younger son of Edward IV, before changing his imposture to Edward, Earl of Warwick.4 Bacon and the sixteenth century historians derived their account of the 1487 insurrection mainly from Polydore Vergil's Anglica Historia, but Vergil, in his manuscript compiled between 1503 and 1513, said only that Simnel counterfeited Warwick.5 The impersonation of York derived from a life of Henry VII, written around 1500 by Bernard André, who failed to name Lambert.6 Bacon's York-Warwick imitation therefore looks like a conflation of the impostures from André and Vergil. -

———————— Number 28 of 2007 ———————— STATUTE LAW REVISION ACT 2007 ———————— ARRAN

Click here for Explanatory Memorandum ———————— Number 28 of 2007 ———————— STATUTE LAW REVISION ACT 2007 ———————— ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Section 1. Definitions. 2. General statute law revision repeal and saver. 3. Specific repeals. 4. Assignment of short titles. 5. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1896. 6. Amendment of Short Titles Act 1962. 7. Miscellaneous amendments to post-1800 short titles. 8. Evidence of certain early statutes, etc. 9. Savings. 10. Short title and collective citation. SCHEDULE 1 Statutes retained PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 1 [No. 28.]Statute Law Revision Act 2007. [2007.] SCHEDULE 2 Statutes Specifically Repealed PART 1 Pre-Union Irish Statutes 1169 to 1800 PART 2 Statutes of England 1066 to 1706 PART 3 Statutes of Great Britain 1707 to 1800 PART 4 Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland 1801 to 1922 ———————— 2 [2007.]Statute Law Revision Act 2007. [No. 28.] Acts Referred to Bill of Rights 1688 1 Will. & Mary, sess. 2, c. 2 Documentary Evidence Act 1868 31 & 32 Vict., c. 37 Documentary Evidence Act 1882 45 & 46 Vict., c. 9 Dower Act 1297 25 Edw. 1, Magna Carta, c. 7 Drainage and Improvement of Lands Supplemental Act (Ireland) (No. 2) 1867 31 & 32 Vict., c. 3 Dublin Hospitals Regulation Act 1856 19 & 20 Vict., c. 110 Evidence Act 1845 8 & 9 Vict., c. 113 Forfeiture Act 1639 15 Chas. -

The Life and Northern Career of Richard III Clara E

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2014 Richard, son of York: the life and northern career of Richard III Clara E. Howell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Howell, Clara E., "Richard, son of York: the life and northern career of Richard III" (2014). LSU Master's Theses. 2789. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2789 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RICHARD, SON OF YORK: THE LIFE AND NORTHERN CAREER OF RICHARD III A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Clara E. Howell B.A. Louisiana State University, 2011 August 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people to thank for their help and support throughout the process of researching and writing this thesis, as well as through the three years of graduate school. First, I would like to thank my committee in the Department of History. My advisor, Victor Stater, has been a constant source of guidance and support since my days as an undergraduate. It was his undergraduate lectures and assignments that inspired me to continue on to my Masters degree. -

The Unseen Elizabeth Woodville REGISTER STAFF

....... s Richard III Society, Inc. Volume XXIV No. 3 Fall, 2005 The Unseen Elizabeth Woodville REGISTER STAFF EDITOR: Carole M. Rike 14819 Flowerwood Drive • Houston, TX 77062 281-488-3413 ° 504-952-4984 (cell) email: [email protected] ©2005 Richard III Society, Inc., American Branch. No part may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means — mechanical, RICARDIAN READING EDITOR: Myrna Smith electrical or photocopying, recording or information storage retrieval — 2784 Avenue G • Ingleside, TX 78362 without written permission from the Society. Articles submitted by (361) 332-9363 • email: [email protected] members remain the property of the author. The Ricardian Register is published four times per year. Subscriptions are available at $20.00 annually. ARTIST: Susan Dexter 1510 Delaware Avenue • New Castle, PA 16105-2674 In the belief that many features of the traditional accounts of the character and career of Richard III are neither supported by sufficient CROSSWORD: Charlie Jordan evidence nor reasonably tenable, the Society aims to promote in every [email protected] possible way research into the life and times of Richard III, and to secure a re-assessment of the material relating to the period, and of the role in English history of this monarch The Richard III Society is a nonprofit, educational corporation. In This Issue Dues, grants and contributions are tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law. Elizabeth Woodville’s Families Dues are $35 annually for U.S. Addresses; $40 for international. Kathleen Spaltro . 4 Each additional family member is $5. Members of the American Sites for Elizabeth Woodville’s Families, Society are also members of the English Society.