Flippin' the Script, Joustin' from the Mouth: a Systemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: a Content Analysis

The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman in Rap Videos: A Content Analysis Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Manriquez, Candace Lynn Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 03:10:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624121 THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN IN RAP VIDEOS: A CONTENT ANALYSIS by Candace L. Manriquez ____________________________ Copyright © Candace L. Manriquez 2017 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2017 Running head: THE SYMBOLIC ANNIHILATION OF THE BLACK WOMAN 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR The thesis titled The Symbolic Annihilation of the Black Woman: A Content Analysis prepared by Candace Manriquez has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for a master’s degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgement of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Livin' a Boss' Life

REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED WEST COAST RAP SHIT TURF TALK BEEDA WEEDA CLYDE CARSON MAC MALL DAMANI & MORE BAY AREA AMBASSADOR - LIVIN’ AE BOSS’40 LIFE * WEST COAST DJs SOUND OFF ON MIXTAPE DRAMA * THE GAME’S BROTHER BIG FASE100 * BUMSQUAD’S LATIN PRINCE & MORE // OZONE WEST Publisher EDITOR’S NOTE Julia Beverly Editor-IN-Chief N. Ali Early Music Editor Randy Roper Art Director Tene Gooden Contributors D-Ray DJ BackSide Joey Colombo Toby Francis Wendy Day Street Reps Anthony Deavers Bigg P-Wee Dee1 Demolition Men DJ E-Z Cutt DJ Jam-X DJ K-Tone DJ Quote MUST BE DREAMIN’ DJ Strong & DJ Warrior John Costen Kewan Lewis Lisa Coleman Maroy been living in Atlanta a good decade and I still haven’t gotten completely accus- Rob J Official tomed to it, nor have I embraced it all the way. What can I say? I’m a Bayboy to the Rob Reyes heart. Anyone who knows me, knows that I rep the Bay – all day, every day. I went Sherita Saulsberry I’vehome for Xmas and all I could think about was what kind of Bay Tees I was gonna snatch so I could have William Major the option of reppin’ my soil every day for two weeks straight (that’s 14, but who’s counting?). Took Moms in there and scooped about eight of ‘em REAL QUICK (already had 6). Alas, I didn’t leave my heart in San Francisco ala Tony Bennett. It’s somewhere in Tha Rich! But I gotta love the A and I gotta give JB props for bringing me on board, ‘cause without the move from Orlando this opportunity may have never cracked off. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

G-Eazy & DJ Paul Star in the Movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 in the BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED

STREET CONSEQUENCES MAGAZINE Exclusive Pull up a seat as Antonio Servidio take us through his life as a Legitimate Hustler & Executive Producer of the movie “Tunnel Vision” Featuring 90’s Bay Area Rappers Street Consequences Presents E-40, Too Short, B-Legit, Spice 1 & The New Talent of Rappers KB, Keak Da Sneak, Rappin 4-Tay Mac Fair & TRAP Q&A with T. A. Corleone Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences G-Eazy & DJ Paul star in the movie Tunnel Vision October/November 2017 IN THE BAY AREA YOUR VIEW IS UNLIMITED October/November 2017 2 October /November 2017 Contents Publisher’s Word Exclusive Interview with Antonio Servidio Featuring the Bay Area Rappers Meet the Ladies of Street Consequences Street Consequences presents new talent of Rappers October/November 2017 3 Publisher’s Words Street Consequences What are the Street Consequences of today’s hustling life- style’s ? Do you know? Do you have any idea? Street Con- sequences Magazine is just what you need. As you read federal inmates whose stories should give you knowledge on just what the street Consequences are. Some of the arti- cles in this magazine are from real people who are in jail because of these Street Consequences. You will also read their opinion on politics and their beliefs on what we, as people, need to do to chance and make a better future for the up-coming youth of today. Stories in this magazine are from big timer in the games to small street level drug dealers and regular people too, Hopefully this magazine will open up your eyes and ears to the things that are going on around you, and have to make a decision that will make you not enter into the game that will leave you dead or in jail. -

Zaytoven from a to Zay Pdf

Zaytoven from a to zay pdf Continue This biography of a living person needs additional appointments for verification. Please help by adding reliable sources. Contentious material about people who are not sourced or bad source should be removed immediately, especially if potentially defamation or harmful. Search sources: Zaytoven – news · newspapers · books · the scholar · JSTOR (February 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) ZaytovenDotson on a panel of the SAE Institute; 2015 Additional information Birth nameXavier Lamar DotsonBorn (1980-01-12) January 12, 1980 (age 40)Frankfurt, GermanyOriginAtlanta, Georgia, U.S.GenresHip hoptrapOccupation(s)Record producer jockeykeyboardistsongwriterInstrumentsMPCkeyboardpianoYears active1997–presentLabelsZaytown1017 Family territoryMotownAlemocia Acts fromfutureMigos 21 SavageChief KeefGucci ManeBoosie BadaZzOJ da JuicemanLil KeedLil GotitLecraeUsherWaka Flocka FlameWebsitezaytovenbeatz.com Xavier Lamar Dotson (born January 12, 1980), known professionally as Zaytoven, World War II was a September 17, 1936, in the capital by the university of Atlanta. [2] She has launched collaborative projects with artists such as Usher, Future, Gucci Mane and Lecrae. He has also produced songs for artists such as Chief Keef. [4] Zaytoven won a Grammy Award in 2011 for his contribution to Raymond v of Usher. Raymond album,[5][6] as co-producer and writer of the single Papers with Sean Garrett. [8] Her debut album was released in 2018. The early years of Zaytoven's life spent a lot of time in the church growing up, as his father was a preacher when he did not work for the Army. [9] Zaytoven learned to play instruments through church bands along with his three younger brothers. He recorded towards playing the piano and organ. -

Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Empowerment and Enslavement: Rap in the Context of African-American Cultural Memory Levern G. Rollins-Haynes Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES EMPOWERMENT AND ENSLAVEMENT: RAP IN THE CONTEXT OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURAL MEMORY By LEVERN G. ROLLINS-HAYNES A Dissertation submitted to the Interdisciplinary Program in the Humanities (IPH) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Levern G. Rollins- Haynes defended on June 16, 2006 _____________________________________ Charles Brewer Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________________ Xiuwen Liu Outside Committee Member _____________________________________ Maricarmen Martinez Committee Member _____________________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member Approved: __________________________________________ David Johnson, Chair, Humanities Department __________________________________________ Joseph Travis, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii This dissertation is dedicated to my husband, Keith; my mother, Richardine; and my belated sister, Deloris. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Very special thanks and love to -

Super ACRONYM - Round 5

Super ACRONYM - Round 5 1. After retiring, this athlete founded the Crest Computer Supply Company and served as the athletic director of Southern Illinois University. This player claimed to only need "18 inches of daylight" and led the NFL in the majority of both rushing and kick return categories in 1966. This Wichita-born athlete was often called the (*) "Kansas Comet." This man's autobiography I Am Third detailed his close relationship with his roommate of a different race, which was adapted into a film in which this man was played by Billy Dee Williams. The late Brian Piccolo was a dear friend of, for 10 points, what Bears running back? ANSWER: Gale (Eugene) Sayers <Nelson> 2. The Tiny Desk, a prototype devised by this character, allows people to alleviate stress by flipping their office desks without creating a huge mess. This man sings about a "Leprechaun on the lawn at Boston Common" and a creature "the size of (*) Luxembourg" as part of a "Kaiju Rap" inspired by the film Reptilicus. This character is tormented by Max, an assistant played by Patton Oswalt, and Kinga, played by Felicia Day. For 10 points, name this "mug in a yellow jumpsuit" who is trapped "on the dark side of the moon" in the revival of Mystery Science Theater 3000 and is played by a namesake comedian with the surname Ray. ANSWER: Jonah Heston (accept either underlined portion; do not accept or prompt on "(Jonah) Ray") <Vopava> 3. After the Creolettes were renamed for these things, they recorded the song "The Wallflower (Dance With Me Henry)" with Etta James. -

JT the Bigga Figga Playaz N the Game Mp3, Flac, Wma

JT The Bigga Figga Playaz N The Game mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Playaz N The Game Country: US Released: 1994 Style: Thug Rap, Gangsta MP3 version RAR size: 1743 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1135 mb WMA version RAR size: 1919 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 951 Other Formats: TTA MP1 AC3 DTS AAC MP3 AA Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Its About That Time Peep Game A2 Featuring – D-Moe Game Recongize Game A3 Featuring – Mac Mall A4 Mr. Millimeter Out 2 Get Cha A5 Featuring – D-Moe Did You Get The Dank A6 Featuring – 4-Tay* B1 The Whole Thang B2 The Paper Chase Back To Tha Shit B3 Featuring – D-Moe, San Quinn Doin' Dirt B4 Featuring – Gigolo G B5 Foul From The Start B6 You Can't Play A Playa Companies, etc. Published By – Get Low Publishing Distributed By – SMG Solar Music Group Credits Producer – JT the Bigga Figga Notes Cassette version says "Get Low Records" Second Pressing. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 7 8258-70001-4 6 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year JT The Bigga Playaz N The Game (CD, Get Low GLR001-CD GLR001-CD US 1993 Figga Album) Recordz JT The Bigga Playaz N The Game (Cass, Get Low GLR001 GLR001 US 1994 Figga Album) Recordz JT The Bigga Playaz N The Game (CD, Get Low GLR001 GLR001 US 1994 Figga Album, RE) Recordz JT The Bigga Playaz N The Game (CD, Get Low P2 50554 P2 50554 US 1996 Figga Album, RE) Recordz JT The Bigga Playaz N The Game (CD, Get Low SMC141 SMC141 US 2006 Figga Album, RE) Recordz Related Music albums to Playaz N The Game by JT The Bigga Figga The Game - Untold Story (Chopped And Screwed) Lil Ric - Deep N Tha Game Bigga World - Oh My God / My Perspective Bigga Rankin - Bigga Is Betta Vol. -

Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom Kevin Kshitiz Bhatia

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Law School Student Scholarship Seton Hall Law 5-1-2014 Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom Kevin Kshitiz Bhatia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship Recommended Citation Bhatia, Kevin Kshitiz, "Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom" (2014). Law School Student Scholarship. 441. https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship/441 Ozymandias: Kings without a Kingdom Ozymandias is an English sonnet written by poet Percy Shelly in 1818. The sonnet reads: “I met a traveller from an antique land who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, and wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, tell that its sculptor well those passions read which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, the hand that mocked them and the heart that fed: And on the pedestal these words appear: ’My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare the lone and level sands stretch far away.”75 There are several conflicting accounts regarding Shelly’s inspiration for the sonnet, but the most widely accepted story tells that Percy Shelly was inspired by the arrival in Britain of a statute of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II. Observing the irony of a pharaoh’s statute, which was created to glorify the omnipotence of the ruler, being carried into port as a mere collectible in a museum, Shelly wrote the sonnet to summarize a particular irony that presents itself repeatedly throughout history. -

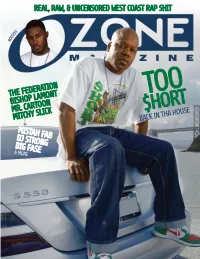

Mistah Fab Dj Strong Big Fase the Federation Bishop

REAL, RAW, & UNCENSORED WEST COAST RAP SHIT THE FEDERATION BISHOP LAMONT MR. CARTOON MITCHY SLICK TOO MISTAH FAB $HORT DJ STRONG back in tha house BIG FASE & MORE OZONE WEST // 1 2 // OZONE WEST editor’s note Publisher Julia Beverly Editor-IN-Chief N. Ali Early Art Director Tene Gooden Music Editor Randy Roper ADVERTISING SALES Che Johnson Isaiah Campbell no id Contributors D-Ray and my ninja finally caught Tyler Perry’s men whose destiny is to go to jail? Meanwhile, their DJ BackSide latest flick Daddy’s Little Girls and I female counterparts find their way through college, Joey Colombo Memust say I was pleasantly surprised. graduate school and then the corporate world, if Regi Mentle I remember him talking on the radio about how they so choose. Wendy Day America didn’t want to accept the idea of a single Black father raising children… and wanting to do We talk about Hip Hop being grown with the button Street Reps it. So I got to thinking – because I do that – and down shirts and all the materialistic bullshit that Anthony Deavers it struck a chord. A week prior to taking in that comes with it, but it doesn’t mean anything if we Bigg P-Wee movie I watched a disturbing video on the news. don’t look out for each other. Perry addressed it in Dee1 The next day there were endless Internet streams of the movie when Gabrielle Union’s character bel- Demolition Men the same video, which I’m sure most of conscious lowed that if she saw “another 30 year old brotha DJ E-Z Cutt America has been made aware of: two babies wearing a throwback” she was going to scream… DJ Jam-X smoking weed in the presence of their uncle and and then she did (both). -

Sociolinguistics and Language Education

Sociolinguistics and Language Education 1790.indb i 5/13/2010 3:43:18 PM NEW PERSPECTIVES ON LANGUAGE AND EDUCATION Series Editor: Professor Viv Edwards, University of Reading, Reading, Great Britain Series Advisor: Professor Allan Luke, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia Two decades of research and development in language and literacy education have yielded a broad, multidisciplinary focus. Yet education systems face constant economic and technological change, with attendant issues of identity and power, community and culture. This series will feature critical and interpretive, disciplinary and multidisciplinary perspectives on teaching and learning, language and literacy in new times. Full details of all the books in this series and of all our other publications can be found on http://www.multilingual-matters.com, or by writing to Multilingual Matters, St Nicholas House, 31–34 High Street, Bristol BS1 2AW, UK. 1790.indb ii 5/13/2010 3:43:19 PM NEW PERSPECTIVES ON LANGUAGE AND EDUCATION Series Editor: Professor Viv Edwards Sociolinguistics and Language Education Edited by Nancy H. Hornberger and Sandra Lee McKay MULTILINGUAL MATTERS Bristol • Buffalo • Toronto 1790.indb iii 5/13/2010 3:43:19 PM Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. Sociolinguistics and Language Education/Edited by Nancy H. Hornberger and Sandra Lee McKay. New Perspectives on Language and Education: 18 Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Sociolinguistics. 2. Language and education. 3. Language and culture. I. Hornberger, Nancy H. II. McKay, Sandra. P40.S784 2010 306.44–dc22 2010018315 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library. -

Messy Marv Messy Situationz Mp3, Flac, Wma

Messy Marv Messy Situationz mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Messy Situationz Country: US Released: 1996 Style: Gangsta MP3 version RAR size: 1433 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1829 mb WMA version RAR size: 1261 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 527 Other Formats: MPC RA VQF MOD AU AIFF DXD Tracklist Hide Credits Ghetto Blues 1 Featuring – Maverick Neal, The Madd Felon 2 Children's Story PHD's 3 Featuring – HK In The Game 4 Featuring – Sandy Wyatt 5 Dank Session 6 Messy Situationz A Poor Man's Dream 7 Featuring – JT The Bigga Figga, San Quinn On The DL 8 Featuring – Sandy Wyatt, Trev-G Ghetto Glamour Hood Hoe's 9 Featuring – Maverick Neal Game To Be $old & Told 10 Featuring – Leysha Too Hot 11 Featuring – Skyler Jett Freak Down 12 Featuring – Trev-G 13 The Back Streets 14 The Chronic Credits Engineer – The Sekret Service Executive Producer – Ammo Entertainment, DeVaughn Hartzfield, Messy Marv, Michael Aissa, Michael Ohayon, Shaka Dumetz Mixed By – The Sekret Service Producer – G-Man Stan (tracks: 10), JT The Bigga Figga (tracks: 13), Messy Marv, The Sekret Service Notes (C)(P)1996 Trigga Lock Records / Ammo Entertainment. This album contains no samples of pre-recorded music. Recorded at Pajamas Studio, Oakland, CA. Mixed at Live Oak Studio, Berkeley, CA.; Except "The Back Streets" recorded & mixed at The Labb, San Francisco, CA. & "Game To Be $old & Told" recorded & mixed at Find Away Studio, San Francisco, CA. Mastered at Bernie Grundman Mastering, Los Angeles, CA. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Messy Messy Situationz (CD, Phonetic, 50591 50591 Germany 1997 Mary* Album) Semaphore Messy Situationz (CD, TRL 6453-2 Messy Marv Trigga Lock TRL 6453-2 US 1996 Album) Messy Situationz (2xCD RTE 00111 Messy Marv Scalen Muzik Inc.