The First Business Computer: a Case Study in User-Driven Innovation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153

Appendix 1 Technical Details of the Elliott 152 and 153 Introduction The Elliott 152 computer was part of the Admiralty’s MRS5 (medium range system 5) naval gunnery project, described in Chap. 2. The Elliott 153 computer, also known as the D/F (direction-finding) computer, was built for GCHQ and the Admiralty as described in Chap. 3. The information in this appendix is intended to supplement the overall descriptions of the machines as given in Chaps. 2 and 3. A1.1 The Elliott 152 Work on the MRS5 contract at Borehamwood began in October 1946 and was essen- tially finished in 1950. Novel target-tracking radar was at the heart of the project, the radar being synchronized to the computer’s clock. In his enthusiasm for perfecting the radar technology, John Coales seems to have spent little time on what we would now call an overall systems design. When Harry Carpenter joined the staff of the Computing Division at Borehamwood on 1 January 1949, he recalls that nobody had yet defined the way in which the control program, running on the 152 computer, would interface with guns and radar. Furthermore, nobody yet appeared to be working on the computational algorithms necessary for three-dimensional trajectory predic- tion. As for the guns that the MRS5 system was intended to control, not even the basic ballistics parameters seemed to be known with any accuracy at Borehamwood [1, 2]. A1.1.1 Communication and Data-Rate The physical separation, between radar in the Borehamwood car park and digital computer in the laboratory, necessitated an interconnecting cable of about 150 m in length. -

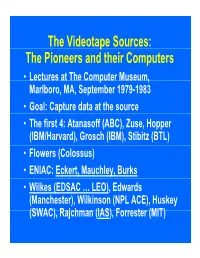

P the Pioneers and Their Computers

The Videotape Sources: The Pioneers and their Computers • Lectures at The Compp,uter Museum, Marlboro, MA, September 1979-1983 • Goal: Capture data at the source • The first 4: Atanasoff (ABC), Zuse, Hopper (IBM/Harvard), Grosch (IBM), Stibitz (BTL) • Flowers (Colossus) • ENIAC: Eckert, Mauchley, Burks • Wilkes (EDSAC … LEO), Edwards (Manchester), Wilkinson (NPL ACE), Huskey (SWAC), Rajchman (IAS), Forrester (MIT) What did it feel like then? • What were th e comput ers? • Why did their inventors build them? • What materials (technology) did they build from? • What were their speed and memory size specs? • How did they work? • How were they used or programmed? • What were they used for? • What did each contribute to future computing? • What were the by-products? and alumni/ae? The “classic” five boxes of a stored ppgrogram dig ital comp uter Memory M Central Input Output Control I O CC Central Arithmetic CA How was programming done before programming languages and O/Ss? • ENIAC was programmed by routing control pulse cables f ormi ng th e “ program count er” • Clippinger and von Neumann made “function codes” for the tables of ENIAC • Kilburn at Manchester ran the first 17 word program • Wilkes, Wheeler, and Gill wrote the first book on programmiidbBbbIiSiing, reprinted by Babbage Institute Series • Parallel versus Serial • Pre-programming languages and operating systems • Big idea: compatibility for program investment – EDSAC was transferred to Leo – The IAS Computers built at Universities Time Line of First Computers Year 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 ••••• BTL ---------o o o o Zuse ----------------o Atanasoff ------------------o IBM ASCC,SSEC ------------o-----------o >CPC ENIAC ?--------------o EDVAC s------------------o UNIVAC I IAS --?s------------o Colossus -------?---?----o Manchester ?--------o ?>Ferranti EDSAC ?-----------o ?>Leo ACE ?--------------o ?>DEUCE Whirl wi nd SEAC & SWAC ENIAC Project Time Line & Descendants IBM 701, Philco S2000, ERA.. -

A Historical Perspective of the Development of British Computer Manufacturers with Particular Reference to Staffordshire

A historical perspective of the development of British computer manufacturers with particular reference to Staffordshire John Wilcock School of Computing, Staffordshire University Abstract Beginning in the early years of the 20th Century, the report summarises the activities within the English Electric and ICT groups of computer manufacturers, and their constituent groups and successor companies, culminating with the formation of ICL and its successors STC-ICL and Fujitsu-ICL. Particular reference is made to developments within the county of Staffordshire, and to the influence which these companies have had on the teaching of computing at Staffordshire University and its predecessors. 1. After the second world war In Britain several computer research teams were formed in the late 1940s, which concentrated on computer storage techniques. At the University of Manchester, Williams and Kilburn developed the “Williams Tube Store”, which stored binary numbers as electrostatic charges on the inside face of a cathode ray tube. The Manchester University Mark I, Mark II (Mercury 1954) and Atlas (1960) computers were all built and marketed by Ferranti at West Gorton. At Birkbeck College, University of London, an early form of magnetic storage, the “Birkbeck Drum” was constructed. The pedigree of the computers constructed in Staffordshire begins with the story of the EDSAC first generation machine. At the University of Cambridge binary pulses were stored by ultrasound in 2m long columns of mercury, known as tanks, each tank storing 16 words of 35 bits, taking typically 32ms to circulate. Programmers needed to know not only where their data were stored, but when they were available at the top of the delay lines. -

Resurrection

Issue Number 10 Summer 1994 Computer Conservation Society Aims and objectives The Computer Conservation Society (CCS) is a co-operative venture between the British Computer Society and the Science Museum of London. The CCS was constituted in September 1989 as a Specialist Group of the British Computer Society (BCS). It thus is covered by the Royal Charter and charitable status of the BCS. The aims of the CCS are to o Promote the conservation of historic computers o Develop awareness of the importance of historic computers o Encourage research on historic computers Membership is open to anyone interested in computer conservation and the history of computing. The CCS is funded and supported by a grant from the BCS, fees from corporate membership, donations, and by the free use of Science Museum facilities. Membership is free but some charges may be made for publications and attendance at seminars and conferences. There are a number of active Working Parties on specific computer restorations and early computer technologies and software. Younger people are especially encouraged to take part in order to achieve skills transfer. The corporate members who are supporting the Society are Bull HN Information Systems, Digital Equipment, ICL, Unisys and Vaughan Systems. Resurrection The Bulletin of the Computer Conservation Society ISSN 0958 - 7403 Number 10 Summer 1994 Contents Society News Tony Sale, Secretary 2 Evolution of the Ace drum system Fred Osborne 3 Memories of the Manchester Mark I Frank Sumner 9 Ferranti in the 1950s Charlie Portman 14 Very early computer music Donald Davies 19 Obituary: John Gray Doron Swade 21 Book Review - the Leo story 22 Letters to the Editor 24 Letters Extra - on identifying Pegasi 27 Working Party Reports 29 Forthcoming Events 32 Society News Tony Sale, Secretary Things have been progressing well for the Society at Bletchley Park. -

The Women of ENIAC

The Women of ENIAC W. BARKLEY FRITZ A group of young women college graduates involved with the EFJIAC are identified. As a result of their education, intelligence, as well as their being at the right place and at the right time, these young women were able to per- form important computer work. Many learned to use effectively “the machine that changed the world to assist in solving some of the important scientific problems of the time. Ten of them report on their background and experi- ences. It is now appropriate that these women be given recognition for what they did as ‘pioneers” of the Age of Computing. introduction any young women college graduates were involved in ties of some 50 years ago, you will note some minor inconsiskn- NI[ various ways with ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integra- cies, which arc to be expected. In order to preserve the candor and tor And Computer) during the 1942-195.5 period covering enthusiasm of these women for what they did and also to provide ENIAC’s pre-development, development, and 10-year period of today’s reader and those of future generations with their First-hand its operational usage. ENIAC, as is well-known, was the first accounts, I have attempted to resolve only the more serious incon- general purpose electronic digital computer to be designed, built, sistencies. Each of the individuals quoted, however, has been and successfully used. After its initial use for the Manhattan Proj- given an opportunity to see the remarks of their colleagues and to ect in the fall of 194.5 and its public demonstration in February modify their own as desired. -

Company Histories

British companies delivering digital computers in the period 1950 – 1965. Elliott Brothers (London) Ltd. and Elliott-Automation. The Elliott Instrument Company was founded in 1804. By the 1870s, telegraph equipment and electrical equipment were added to the company’s products. Naval instrumentation became an area of increasing importance from about 1900, the company working with the Admiralty to develop Fire Control (ie gunnery control) electro-mechanical analogue computers. Elliott Brothers (London) Ltd. provided fire-control equipment to the Royal Navy from 1908 until shortly after the end of the Second World War. By 1946 the company’s main factory at Lewisham in south London had become a technological backwater. Although still skilled in manufacturing electro-mechanical equipment and precision electrical instrumentation, it had been bypassed by the huge war- time flow of government contracts for radar and allied electronic equipment. Compared with firms such as Ferranti Ltd., there was practically no electronic activity at Elliott’s Lewisham factory. The company actually traded at a loss between 1946 and 1951. Somewhat surprisingly, fresh discussions between the Admiralty and Elliott Brothers (London) Ltd. started in 1946, with the objective of persuading the company to host a new research team whose prime objective was to work on an advanced digital electronic Fire Control system and target-tracking radar. The Admiralty leased to the company a redundant factory at Borehamwood in Hertfordshire. This became known as Elliott’s Borehamwood Research Laboratory. It was at Borehamwood that a team of specially- recruited young scientists and engineers designed and built several secret digital computers for various classified projects. -

Science Museum Library and Archives Science Museum at Wroughton Hackpen Lane Wroughton Swindon SN4 9NS

Science Museum Library and Archives Science Museum at Wroughton Hackpen Lane Wroughton Swindon SN4 9NS Telephone: 01793 846222 Email: [email protected] LAV/1/1/UK2 Material relating to English Electric computers Compiled by Professor Simon Lavington LAV/1/1/UK2 April 1959 Programming Buff- bound foolscap typed manual for the document, approximately computer 200 pages. This manual DEUCE. RAE given to SHL by John Farnborough, Coales, November 1999. Tech Note MS38. D G Burnett-Hall & P A Samet c. 1995 & Notes on Four pages of notes, 2007 probable provenance Keith Titmuss, deliveries of Kohn Barrett, Jeremy EE DEUCE Walker & David Leigh. (For a corrected list, see the Our Computer Heritage website. 1999 P J Walker’s Jeremy Walker retired from notes on KDF ICL Kidsgrove in 1991. He 6, KDF7, KDF8 worked on the KDP10 at and KDP10. English Electric Kidsgrove in 1961. 1999 George Vale’s George was involved in the notes on KDN2, specification of the KDF7 and M2140, a 16-bit process M2140. control computer whose design was begun in about 1966. GEC scrapped the project in 1966 although by then ‘quite a number had been sold’ and installations continued up to about 1973. c. 1959 KDP10: a 6 page illustrated glossy decisive brochure, EE publication advance in ES/202. automatic data processing. C. 1961 KDF9: very 30 page illustrated glossy high speed brochure, EE publication data DP/103. Also, a photocopy processing of this. system for commerce, industry, science. c. 1965 KDF9 Undated publication programming 1002mm/1000166, produced manual by English Electric-Leo- Marconi. -

Lac-TM-544-B PUB DATE Km:: BO GRANT :1=7-G-7B-0043 NOTE 3:24:; Figure

DOCUMEr7 RESUHE ED 202 095 EA 013 AUTHOR Lambright, N.Benty; And Othe.s TITLE 1.:lucational InnoY7ation as a F 3cess of :alition-Buildi=7:. A Study Organilt_:=.2. Decision-,Making., Tolume 3e Studies Educational InncTations in '\E:, ester L..z.d York. INSTITUTION S-Frracuse Researcn Corp., Sy=:,z;:se, N.Y. -SPONS AGENC: la:zional Inst. of Education (4ash:.agtora, D.C. REPORT NO :lac-TM-544-B PUB DATE km:: BO GRANT :1=7-G-7B-0043 NOTE 3:24:; Figure. 3 and:occasiol. appen:Aces may remroduce poorly. For a accument,see TA 01Z EDRS PRICE . I201/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Ldministrative Organization Cam:, _zsisted Instruction;,CompuLer Instructi.:n; :ommuter Oriented Programs; *Decisicr. l_sabilities; Educational Comple;:es Innovation; Elementary Secondar= Exceptional Persois; Free Choice 2-a ::en Progrs: House Plan; Informal OrTanizatio:._: .L.aamrAtocy .7ohools; Magnet Schools; Mainst-zei.,4-z..---c;MatIzgeme=t :nformation Systems; *OrgtmizatioL4.._ -reaopient; kOrzanizational EffectiveLess; 2ara:r.ofessz.nral School Personnel; Power Structui-e: R. IElarc-E; 0School Districts; Special 'Education: i:tudemt Lachatge Programs IDENTIFIERS 1.-fducation for A21 Handicapped Childrea ict: Project luzigue; *Rochester City School .7,;.s.-;==t 'L4 *Syracuse 2.-Lty Schools NY; UrbaniSliburhian Interiztztriz:t 1.-L-ansfer Program ABSTRACT fzis document contains/the full texl_ of te. ca-Li_ studies prepared b,- the Syracuse Research Corpocati-7_ 5o= _J:s 1,11:,:pose. of examining the c7.ganizational processes involved :...at.,-ffetz.ve educational innolion at the school didtrict level- ;no ;e. in two urban distri:Ts were examined. In th Syracuse City 3cLc;3_ District these inaovations involved the oliowing: resco.e.af, t- the need for educatira children with hAndicap ing condition z, .z_-;:. -

MY WORKING LIFE the Story of a 20Th Century Computer Programmer

MY WORKING LIFE The story of a 20th century computer programmer An Autobiography by D. J. Pentecost November 2018, with corrections in 2020 © 2018, 2020 ISBN 978-0-9518719-3-5 D. J. Pentecost, 2. St. Andrews Close, Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire, LU7 1DB To Kai and other members of my family. To historians of the computer industry. ii CONTENTS Chapter 1 The Shortlands Press Page 1 Chapter 2 The National Physical Laboratory Page 2 Chapter 3 Elliott Brothers (London) Ltd Page 7 Chapter 4 Mills Associates Limited, ISIS Page 29 Chapter 5 Dataco Limited Page 41 Chapter 6 Unit Trust Services Ltd Page 43 Chapter 7 CMG (City of London) Limited Page 50 Chapter 8 Attwood Computer Projects Limited Page 53 Chapter 9 Coward Chance, Clifford Chance Page 56 Chapter 10 I.T. Consultant Page 70 Chapter 11 Our Computer Heritage Page 85 iii Chapter 1: THE SHORTLANDS PRESS The Shortlands Press former premises (2015 photo), and a Thompson letterpress machine In some of the school holidays around 1950, I worked in my father’s printing shop at 650/652 High Road, Leyton, E10; the business was listed in the local Chamber of Commerce Trade Directory for 1957-58, and for some earlier years too, certainly in 1949, and up to 1974 in Kelly’s directories. The business was opened in 1946 with Percy Budd, my father’s business partner, whom I think he had met during their service in the Royal Marines during the second world war. My father and I travelled by bus from North Finchley to Leyton, leaving early in the morning. -

Peru2 User Guide

1:::D1""\ Systems PLr\.'-L Corporation PERU2 USER GUIDE March 1984 Copyrisht(C) 198i International Computers LiMited Lovelace Road Bracknell Berkshire RG12 iSN England CopyrishtCC) 198i PERQ Systems Corporation 2600 Liberty Avenue P. O. Box 2600 Pittsbursh, PA 15Z30 (HZ) 355-0900 This document is not to be reproduced in any form or transmitted in whole or in part, without the prior written authorization of PERC Systems Corporation. The information in this document is subject to change without notice and should not be construed as a commitment by PERC Systems Corporation. The company assumes no responsibility for any errors that may appear in this document. PERC Systems Corporation will make every effort to keep customers apprised of all documentation changes as quickly as possible. The Reader's Comments card is distributed with this document to request users' critical evaluation to assist us in preparing future documentation. PERC and PERQ2 are trademarks of PERC Systems Corporation. - ii - User Guide - Preface Karch 5, 1984 Preface How to Use This Guide This guide introduces you to using PERQ Systems hardware. The guide is intended for the user who has some knowledge of computers, but who is not necessarily a expert. This preface contains: Details of publications for the PERQ user; General advice on the proper use of PERQ and its peripherals; A reminder to return the customer reply fOMl supplied with PERQ; Space for you to record useful information and telephone numbers. The rest of the guide is divided into two parts. Part 1 contains information on the standard PERQ system. Part 2 provides space for you to file separate publications describing optional peripherals such as printers. -

PUB ATE % I Mar 82 , Ndte '144P.; for Related Document, See IR 010 560

DOCUMENT RESUME 1, - .ED 225 552 IR 010 559 AUTHOR Woolls, Blanche; And Others 0 . TITLE The Use of Technology in the Administration Fdnction , of School Library Media Programs. N INSTITUTION Pittsburgh Univ., Pa. 1 . 'SPONS AGENtY Office of Libraries and Learning Technologies (ED), Washington, DC. PUB ATE % I Mar 82 , NdTE '144p.; For related document, see IR 010 560. Information Analyses (070)' ---Reports Descriptive , PUB'TYPE (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Pliis Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Case Studies; Elementary Secondary Education; *Learning Resources Centers; *Library Administration; *Library Cooperation; Citerature Reviews; *Public Libraxies; School Libraries; *Technology Transfer; l!Use Studies ABSTRACT The state-of-the-art review on the use of technology in the administration of school library media programs and in school library/Public library cooperation which is presented is,based on a literature review and interviews with media specialists from nine states. Additional information is incorporated from a surveyof the 0 status of technology in the Albuquerque Processing Center(New Mexico), The Shawnee Mission, Kansas Schools, and Leavenworth High School (Kansas), and from,commercial vendors queried todetermine use of their online systems by school districts. Theintroduction describes the study methodology, and provides aihistorical perspective through an analysis of pre-1973 literature. A 17-page annotated bibliography of more recent materials,isdivided into the 'major categories of basic information or descriptiva-laformation an applications of technology. Using administrative functions outlined forrthe study, general and specific trends in technologyutilization are analyzed in the areas ai-taChilical services, ciredlation, vcurity systems, information retri val, budgeting an staffing, and other functions. A listing of 23 rec mmendations for future planning concludes the report. -

CA Aion Business Rules Expert Mainframe User Guide

CA Aion® Business Rules Expert Mainframe User Guide r11 This documentation and any related computer software help programs (hereinafter referred to as the "Documentation") are for your informational purposes only and are subject to change or withdrawal by CA at any time. This Documentation may not be copied, transferred, reproduced, disclosed, modified or duplicated, in whole or in part, without the prior written consent of CA. This Documentation is confidential and proprietary information of CA and may not be used or disclosed by you except as may be permitted in a separate confidentiality agreement between you and CA. Notwithstanding the foregoing, if you are a licensed user of the software product(s) addressed in the Documentation, you may print a reasonable number of copies of the Documentation for internal use by you and your employees in connection with that software, provided that all CA copyright notices and legends are affixed to each reproduced copy. The right to print copies of the Documentation is limited to the period during which the applicable license for such software remains in full force and effect. Should the license terminate for any reason, it is your responsibility to certify in writing to CA that all copies and partial copies of the Documentation have been returned to CA or destroyed. TO THE EXTENT PERMITTED BY APPLICABLE LAW, CA PROVIDES THIS DOCUMENTATION "AS IS" WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE, OR NONINFRINGEMENT. IN NO EVENT WILL CA BE LIABLE TO THE END USER OR ANY THIRD PARTY FOR ANY LOSS OR DAMAGE, DIRECT OR INDIRECT, FROM THE USE OF THIS DOCUMENTATION, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS, LOST INVESTMENT, BUSINESS INTERRUPTION, GOODWILL, OR LOST DATA, EVEN IF CA IS EXPRESSLY ADVISED IN ADVANCE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH LOSS OR DAMAGE.