Huang Di to Zhi Bo: a Problem in Historical Epistemology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5022

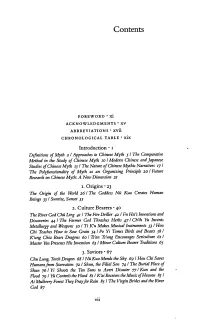

Contents FOREWORD * xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS * XV ABBREVIATIONS * Xvii CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE * xix Introduction • i Definitions of Myth 2 I Approaches to Chinese Myth 5 / The Comparative Method in the Study of Chinese Myth 10 / Modem Chinese and Japanese Studies of Chinese Myth 13 I The Nature of Chinese Mythic Narratives 1 7 1 The Polyfunctionality of Myth as an Organizing Principle 20 I Future Research on Chinese Myth: A New Dimension 21 1. Origins • 23 The Origin of the World 2 6 1 The Goddess Nil Kua Creates Human Beings 33 I Sunrise, Sunset 3s 2. Culture Bearers • 40 The River God Chit Ling 4 1 1 The Fire Driller 42 I Fu Hsi’s Inventions and Discoveries 44 I The Farmer God Thrashes Herbs 4 7 1 Ch’ih Yu Invents Metallurgy and Weapons so I Ti K ’u Makes Musical Instruments 53 I Hou Chi Teaches How to Sow Grain 54 I Po Yi Tames Birds and Beasts 58 I K ’ung Chia Rears Dragons 60 I Ts’an Ts’ung Encourages Sericulture 6 11 Master Yen Presents His Invention 63 I Minor Culture Bearer Traditions 65 3. Saviors • 67 Chu Lung, Torch Dragon 68 I Ntt Kua Mends the Sky 69 I Hou Chi Saves Humans from Starvation 72 / Shun, the Filial Son 74 I The Burial Place of Shun 7 6 1 Yi Shoots the Ten Suns to Avert Disaster 7 7 1 Kun and the Flood 79 I Yii Controls the Flood 811 K ’ai Receives the Music of Heaven 83 I At Mulberry Forest They Pray for Rain 8s I The Virgin Brides and the River God 87 Vll viii Contents 4. -

Three Debates on the Historicity of the Xia Dynasty

Journal of chinese humanities 5 (2019) 78-104 brill.com/joch Faithful History or Unreliable History: Three Debates on the Historicity of the Xia Dynasty Chen Minzhen 陳民鎮 Assistant Researcher, Beijing Language and Culture University, China [email protected] Translated by Carl Gene Fordham Abstract Three debates on the historicity of the Xia dynasty [ca. 2100-1600 BCE] have occurred, spanning the 1920s and 1930s, the late 1900s and early 2000s, and recent years. In the first debate, Gu Jiegang 顧頡剛 [1893-1980], Wang Guowei 王國維 [1877-1927], and Xu Xusheng 徐旭生 [1888-1976] pioneered three avenues for exploring the history of the Xia period. The second debate unfolded in the context of the Doubting Antiquity School [Yigupai 疑古派] and the Believing Antiquity School [Zouchu yigu 走出疑古] and can be considered a continuation of the first debate. The third debate, which is steadily increasing in influence, features the introduction of new materials, methods, and perspectives and is informed by research into the origins of Chinese civilization, a field that is now in a phase of integration. Keywords doubting antiquity – faithful history – unreliable history – Xia dynasty The question of the historicity of the Xia dynasty [ca. 2100-1600 BCE] may be considered from two perspectives. First, did the Xia dynasty exist? Second, on the whole, are the accounts relating to the Xia dynasty as recorded in ancient texts reliable? This perspective tends to center upon the veracity of the his- torical events involving Yu the Great 大禹. Different people at different -

A Study of Luo Yin's Writings of Slandering Shiwei Zhou a Thesis

Understanding “Slandering”: A Study of Luo Yin’s Writings of Slandering Shiwei Zhou A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2020 Committee: Ping Wang William G. Boltz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2020 Shiwei Zhou 2 University of Washington Abstract Understanding “Slandering”: A Study of Luo Yin’s Writings of Slandering Shiwei Zhou Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Ping Wang Department of Asian Languages and Literature This thesis is an attempt to study a collection of fifty-eight short essays-Writings of Slandering- written and compiled by the late Tang scholar Luo Yin. The research questions are who are slandered, why are the targets slandered, and how. The answering of the questions will primarily rely on textual studies, accompanied by an exploration of the tradition of “slandering” in the literati’s world, as well as a look at Luo Yin’s career and experience as a persistent imperial exam taker. The project will advance accordingly: In the introduction, I will examine the concept of “slandering” in terms of how the Chinese literati associate themselves with it and the implications of slandering or being slandered. Also, I will try to explain how Luo Yin fits into the picture. Chapter two will focus on the studies of the historical background of the mid-to-late Tang period and the themes of the essays. Specifically, it will spell out the individuals, the group of people, and the political and social phenomenon slandered in the essays. -

A Study of the Pottery Inscription “Wen Yi 文邑 ”

A Study of the Pottery Inscription “Wen Yi 文邑 ” A Study of the Pottery Inscription “Wen Yi 文邑 ” Feng Shi* Key words: Bronze Age–China Taosi Site (Xiangfen County, Shanxi) Flasks Scripts (Writing) Since the publishing, the red ink-written inscription we know that this has close relationship with Xia Culture. (Figure 1; Li 2001) on pottery flask unearthed from Pit It is well known that the discovery of oracle bone script H4303 at Taosi Site, Xiangfen County, Shanxi Prov- was essential for the identification of the natures of Yinxu ince attracted much attention of academic field. This Culture; then, that whether the Taosi scripts have the flask was dated as the 20th century BCE, which was in same significance to the nature of Taosi Culture is a the chronological scope of the Xia Dynasty. Because of question to which we are eager to get the answers. the studies to the worshipping of God of Land of the The red ink-written inscription of Taosi Culture be- Xia Dynasty and the relevant history facts (Feng 2002a), longed to the same writing system with the oracle bone script of the Shang Dynasty, therefore they could also be seen as the prototype of Chinese characters (Feng 2002b); for this reason, we can decode the Taosi in- scription with the assistance of oracle bone scripts. As for the two characters 2 in this inscription, the first is identified Figure 2. The “Yang as “Wen 文”without disagreement ( )”as the among the researchers, but the decipher- Phonetic ing of the second character has many Component of contradicting results: for example, some 1 3 “Yang (饧)” scholars decipher it as “Yang (Luo in Bronze In- 2001)”, some scholars explained it as Figure 1. -

Natural Law and Normativity in the Huangdi Sijing

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarBank@NUS NATURAL LAW AND NORMATIVITY IN THE HUANGDI SIJING ERNEST KAM CHUEN HWEE (B.A. (Hons), NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2005 Acknowledgements My interest in Huang-Lao began towards the end of my Honors Year and I acknowledge my debt to Prof. Alan Chan, my supervisor, for introducing me to the Huangdi Sijing as a choice for research. Without his encouragement, I may never have thought of furthering my studies beyond my Bachelor’s Degree. Prof. Chan has also been extremely generous in the advice and support he has given me these past three years. For these and also for painstakingly going through the drafts of this dissertation, I am eternally grateful to him. A special word of thanks is due to A/P Tan Sor Hoon. Though she was not my supervisor, she has been extremely patient in answering whatever queries I have had and tolerant of my unexpected and frequent visits all this while. I am grateful too to all who have helped me during my Graduate Seminar Presentation: Kim Hak Ze for agreeing to lend me his laptop (which the projector unfortunately refused to cooperate with), A/P Nuyen Anh Tuan for volunteering to lend me his, and Weng Hong whose Mac I borrowed eventually. A word of thanks also to all my fellow graduate students and A/P Saranindranath Tagore for their comments and suggestions during the seminar. Outside of NUS, I am thankful to the following professors for their invaluable assistance: Prof. -

3.1 the Discovery of the Shang Dynasty

Indiana University, History G380 – class text readings – Spring 2010 – R. Eno 3.1 THE DISCOVERY OF THE SHANG DYNASTY A dramatic beginning In 1899, China was in chaos. Four years earlier, it had been stunned by Japan, which had virtually annihilated the Chinese navy in a single day, aided by their Chinese opponents, whose first cannon shot of the war landed squarely on their own commanding admiral. The political uproar that followed this unmasking of China’s weakness had led to a program of ambitious reform, adopted by a young emperor who daringly gave power to a party of radically progressive Confucians. But the leaders of that party were killed or driven into exile by a coup led by the aging Empress Dowager, and the young emperor was banished to an island prison within the imperial palace grounds in Beijing, where he awaited his eventual death by poison. In the midst of this turmoil, Wang Yirong, a mid-level official who had recently come out of a period of filial retirement in honor of his mother’s death, arrived in Beijing seeking to revive his career and help pull his country out of its desperate trials. Wang was well known as a scholar of ancient script and antiquities, but prior to his mother’s death he had become a political activist as well, raising troops in his home region to help strengthen China against its wealth of foreign adversaries. Upon his arrival in Beijing, Wang secured an appointment as libationer at the Imperial Academy, and he was seeking to use this scholarly position as a means of conveying his patriotic ideas to the Empress Dowager. -

Chinese MYTHOLOGY a to Z

Chinese MYTHOLOGY A TO Z Jeremy Roberts Chinese Mythology A to Z Copyright © 2004 by Jim DeFelice All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roberts, Jeremy, 1956– Chinese mythology A to Z: a young reader’s companion / by Jeremy Roberts.—1st ed. p. cm.—(Mythology A–Z) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4870-3 (hardcover: alk. paper) 1. Mythology, Chinese. I. Title. II. Series. BL1825.R575 2004 299.5′1′03—dc22 2004005341 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Joan M. Toro Cover design by Cathy Rincon Map by Jeremy Eagle Printed in the United States of America VB Hermitage 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS Acknowledgments iv Introduction v Map of China xv A-to-Z Entries 1 Important Gods and Mythic Figures 151 Selected Bibliography 153 Index 154 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank my wife, Debra Scacciaferro, for her help in researching and preparing this book. -

The Shang Dynasty of Ancient China

Teachers’ pack Key Stage 2 Available from 17 March 2015 Rituals and Bronzes: The Shang Dynasty of Ancient China Late Shang dynasty: Ritual food vessel, ding, about 1200 BC. Bronze Teachers’ information This project is aimed at years 3, 4, 5 and 6 and designed to link directly to the history and art and design curriculums. Outline of project In the morning students will tour Compton Verney’s Chinese Collection with a member of the Learning Team exploring objects and artworks from Ancient China. They will investigate the ritual bronzes, exploring their importance and learning about religion and life during the Shang dynasty. Students will have the opportunity to handle an original ritual bronze from Ancient China and discover more about how they were created and their history. In the afternoon students will create their own Chinese vessel using air drying clay. They will be shown different ways to make a clay pot and, taking inspiration from the Chinese bronzes, will base their designs on the ritual vessels they have seen in the morning. Project timing 10am – 2.15pm 1 Compton Verney, Warwickshire, CV35 9HZ T 01926 645560 E [email protected] www.comptonverney.org.uk Registered Charity No 1032478 Important information for your visit This programme will be led by a member of the Learning Team Free coach parking is provided in the main car park. Coaches cannot drop off at the gallery owing to weight restrictions on the Upper Bridge. When arriving please enter through the gate behind the ticket lodge in the main car park The walk from the car park will take approximately 10 minutes.