Iglesia Pentecostal La Luz Del Mundo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Landscapes of Faith: Latin American Religions in the Twenty-First Century

Thornton, Brendan Jamal. 2018. Changing Landscapes of Faith: Latin American Religions in the Twenty-First Century. Latin American Research Review 53(4), pp. 857–862. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.341 BOOK REVIEW ESSAYS Changing Landscapes of Faith: Latin American Religions in the Twenty-First Century Brendan Jamal Thornton University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, US [email protected] This essay reviews the following works: The Cambridge History of Religions in Latin America. Edited by Virginia Garrard-Burnett, Paul Freston, and Stephen C. Dove. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016. Pp. xii + 830. $250.00 hardcover. ISBN: 9780521767330. Native Evangelism in Central Mexico. By Hugo G. Nutini and Jean F. Nutini. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014. Pp. vii + 197. $55.00 hardcover. ISBN: 9780292744127. New Centers of Global Evangelicalism in Latin America and Africa. By Stephen Offutt. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015. Pp. viii + 192. $80.18 hardcover. ISBN: 9781107078321. The Roots of Pope Francis’s Social and Political Thought: From Argentina to the Vatican. By Thomas R. Rourke. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016. Pp. vii + 220. $80.00 hardcover. ISBN: 9781442272712. Latin America today is much more than simply Catholic. To describe it as such would obscure the complicated cultural history of the region while belying the lived experiences of believers and the dynamic transformations in the religious field that have distinguished the longue durée of colonial and postcolonial Latin America. Diversity, heterodoxy, and pluralism have always been more useful descriptors of religion in Latin America than orthodoxy or homogeneity, despite the ostensible ubiquity of Catholic identity. -

The Light of the World in Greater Los Angeles

$ The Journal of CESNUR $ Field Report: The Light of the World in Greater Los Angeles Donald A. Westbrook San Diego State University daw3@protonmail. com We will always be by your side, we have promised to the Lord, We will never stray from your side, you’re Anointed by our God; Our hearts are overflowing and give glories to the Lord, For HE made you an Apostle for salvation of our souls. “All Glory Be to God,” English translation of Andres Orduna Arguello’s “La Gloria Sea a Dios,” The Light of the World Hymnal (2018, 578) ABSTRACT: La Luz del Mundo (LLDM, “The Light of the World”) is a Mexican-born restorationist or “primitive” Christian church that dates to the 1920s. Under the leadership of its second Apostle, Samuel, and now under the guidance of its third Apostle, Naasón, LLDM has increasingly sought to expand its base beyond Mexico (where it is the second largest religious group after the Catholic Church) and now boasts a presence of millions in over 50 nations. This short article, based on fieldwork conducted at churches in southern California, surveys the church’s history in the Greater Los Angeles Area and examines some forms of LLDM community and non-profit engagements. The tight community networks established by LLDM members around places of worship have contributed to social improvements (decreased crime, increases in home value, opening of businesses, increased civic participation and recognition from local authorities, etc.). This phenomenon was evident in East Los Angeles, where hundreds of members live in the neighborhood that surrounds the most significant LLDM temple in the region. -

Congress 2007 Registration Guidebook

Valerie MacRae Valerie Anaheim, California Anaheim, 800 West 800 West Katella Avenue March 1-4, 2007 1-4, March Anaheim Convention Center Anaheim Convention EDUCATION CONGRESS EDUCATION LOS ANGELES RELIGIOUS LOS Registration Guidebook Registration Sponsored by the by Sponsored Angeles of Los Archdiocese Office of Religious Education 3424 Wilshire Boulevard CA 90010-2202 Angeles, Los www.recongress.org LOS ANGELES RELIGIOUS EDUCATION CONGRESS Non-Profit Organization Office of Religious Education U.S. Postage P.O. Box 76955 PAID Los Angeles, CA 90076-0955 Los Angeles, California Permit No. 31795 IMPORTANT! IMPORTANTE! If name and address Si su nombre y dirección are correct, peel off estan correctos, despegue this lable and place it esta etiqueta y peguela on registration form en la forma de inscripción as indicated. como es indicado. 2007 RGB Cover fn 10/9/06 5:40 PM Page 1 OVERVIEW Register online at www.RECongress.org 2007 RECongress Theme Reflection Light poured out wraps all of creation in beauty, in warmth, in love and in solace. The invitation, “Stand in the Light,” nudges us to bask in the incredible radiance of a God whose glory and brightness penetrates everyone, everything and everywhere. Standing in the Light we touch this all-pervasive presence and recognize our inner glory because of it. Christ’s Light shining in our hearts pouring energy and inspiration into us can be a powerful revealer of truth if we allow it to pierce the dark corners of our lives and transform us anew. Acknowledging that “Heaven’s brightness WHAT IS THE LOS ANGELES RECONGRESS? flows from me to you, and on behalf of God, I say that’s right” (B. -

Lets Look @ History & the Process of Elimination

Who started your Church? Lets look @ history & the process of Elimination Date, Origin, Founders of various churches NAME YEAR FOUNDER(S) ORIGIN ORTHODOX CHURCH 1054 (Britannica) Patriarch Bishop Photius Middle East National Churches Went into Schism (formal division) LUTHERAN 1517 (Britannica) Martin Luther (at least 20 groups) Germany ZWINGLIANS 1520’s (Britannica) Ulrich Zwingli Switzerland ANGLICAN 1534 (Britannica) King Henry VIII England CALVINIST 1555 (Britannica) John Calvin Switzerland PRESBYTERIAN 1560 (Britannica) John Knox (at least 10 groups) Scotland CONGREGATIONALIST 1582 (Britannica) Robert Brown England BAPTIST 1605 (Britannica) John Smith (at least 23 branches) Netherlands DUTCH REFORMED 1628 (Britannica) Michaelis Jones New York QUAKERS 1647 (H.of D. p.265) George Fox England METHODIST 1739 (Britannica) John & Charles Wesley (at least 19 groups) London UNITARIAN 1774 (Wikipedia) Theophilus Lindley London EPISCOPALIAN 1789 (Britannica) Samuel Seabury Philadelphia UNITED BRETHREN 1800 (H.of D p.205) Philip Otterbein & Martin Boehm MaryIand DISCIPLES OF CHRIST 1848 (Britannica) Thomas & Alexander Campbell Kentucky PLYMOUTH BRETHREN 1829 (H.of D. p.244-6) John Nelson Derby (at least 8 groups) England ADVENTIST 1830 (Adventist.org) William MiIler (at least 4 Branches) New Hampshire MORMONS (Church of Jesus 1830 (H.of D. p.165) Joseph Smith (at least 7 branches) New York Christ of Latter Day Saints SEVENTH DAY ADVENTIST 1860 (H.of D. p.38) Ellen Gould White Michigan SALVATION ARMY 1865 (H.of D. p.275) William Booth London -

Iglesia De La Luz Del Mundo, Just As Any Religious As in Other Pentecostal Denominations, La Luz Del Body, Plays Different Roles in the Lives of Its Members

By Timothy Wyatt ravelling along Texas Highway 59 in northeast Houston, it eccentric millionaire than a church, but it is one of the many Tis hard to dismiss the golden dome that towers above the houses of worship that can be found around the city. The landscape. Part of a larger Greco-Roman inspired struc- denomination that meets here is not Baptist, Catholic, or ture, the dome stands in sharp contrast to the surrounding even Greek Orthodox; rather a form of Pentecostalism that neighborhood. With a large number of vehicles passing by caters to a primarily Latin American congregation calls the the building each day, only a small number of commuters church home. The church, known as Iglesia de La Luz del and even fewer travelers know the purpose of the opulent Mundo (Light of the World Church), represents the central marble edifi ce. The stark white construction, surrounded Houston congregation of the Mexico-based denomination by a painted metal fence, looks more like a monument to an of the same name. The Romanesque temple of La Luz del Mundo is located between Darden and Bostic Streets in Northeast Houston along Highway 59. The church is the central Houston location for the Mexican-based congregation. Photo by Omar Silva Ambriz courtesy of La Luz del Mundo. 26 • Houston HISTORY • VOL.8 • NO.3 Eusebio Joaquín González established the organiza- tion, formally known as La Iglesia del Dios Vivo, Columna y Apoyo de la Verdad, La Luz del Mundo (The Church of the Living God, Column and Foundation of Truth, The Light of the World), in Monterey, Mexico, on April 6, 1926.1 Called into the service of God through a vision, González changed his name to Aaron and began his service as a minister. -

![Curriculum Vitae [ABRIDGED] June 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6301/curriculum-vitae-abridged-june-2021-2266301.webp)

Curriculum Vitae [ABRIDGED] June 2021

Curriculum Vitae [ABRIDGED] June 2021 Lloyd Barba 17 Barrett Hill Drive Chapin Hall Amherst, MA 01002 EDUCATION June 2016 Ph.D. in American Culture University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Exam Fields: History of the American West & Borderlands; American Race, Ethnicity, & Immigration; American Religious History; Religious Theory & Globalization; -Latino Studies Certificate Dissertation Title: “California’s Cross: A Cultural History of Pentecostals, Race, and Agriculture” December 2011 M.A. in American Culture University of Michigan, Ann Arbor December 2009 B.A. in History and Religious Studies University of the Pacific, Stockton, California Minor: Classics PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE July 2019- Assistant Professor present Amherst College Department of Religion Core Faculty in Latinx and Latin American Studies July 2017- Postdoctoral Fellow (deferred tenure-track appointment to 2019 & secured external grant 2018-19) June 2019 Amherst College Department of Religion July 2016- C3 Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow June 2017 Williams College Latina/o Studies and Religion Barba CV 1 PUBLICATIONS [SELECTED] Monograph “Sowing the Sacred: Mexican Pentecostal Farmworkers in California, 1916-1966” (under contract with Oxford University Press) Edited Volume “Recovering Apostolic Histories & Theologies: Race, Gender, and Culture in Oneness Pentecostalism” Edited with Andrea Johnson and Daniel Ramírez (Advance Contract Penn State University Press July 2020; external reviewers recommend volume for publication May 2021) Peer-Reviewed Journal Articles and Chapters in Edited Volumes “Latina/x/o Pentecostalism” in the Oxford Handbook on Latinx/o/a Christianities ed. Kristy Nabhan-Warren (Oxford University Press; 8,500 words, forthcoming 2021) [invited essay] “Pentecostalism’s Instrumental Faith and Alternative Power: Cesar Chavez and Reies Lopez Tijerina Among Pentecostal Farmworkers 1954-1956” in Faith and Power: Latina/o Religious Politics since 1945 eds. -

Mixtec Evangelicals

M I X T E C EVANGELICALS Globalization, Migration, and Religious Change in a Oaxacan Indigenous Group Mary I. O’Connor MIXTEC EVANGELICALS MIXTEC EVANGELICALS Globalization, Migration, and Religious Change in a Oaxacan Indigenous Group Mary I. O’Connor UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO Boulder © 2016 by University Press of Colorado Published by University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of The Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State University, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, Regis University, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, Utah State University, and Western State Colorado University. ∞ This paper meets the requirements of the ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). ISBN: 978-1-60732-423-2 (cloth) ISBN: 978-1-60732-424-9 (ebook) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data O’Connor, Mary I. Mixtec evangelicals : globalization, migration, and religious change in a Oaxacan indigenous group / by Mary I. O'Connor. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60732-423-2 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-1-60732-424-9 (ebook) 1. Mixtec Indians—Mexico—Oaxaca (State)—Religion. 2. Mixtec Indians—Migrations. 3. Return migrants—Mexico—Oaxaca (State) 4. Return migration—Mexico—Oaxaca (State) 5. Evangelicalism—Mexico—Oaxaca (State) I. Title. F1221.M7O37 2016 299.7'89763—dc23 2015012980 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. -

The Rise of La Luz Del Mundo in Texas

$ The Journal of CESNUR $ The Rise of La Luz del Mundo in Texas J. Gordon Melton Baylor University, Waco, Texas [email protected] ABSTRACT: La Luz del Mundo, a large and relatively new Christian denomination, originated in Mexico in 1926 even as the Roman Catholic religious hegemony was being challenged by a spectrum of Protestant and post-Protestant groups. The new church has complex roots, one being the still relatively new Pentecostal movement, which spread from Los Angeles into Mexico early in the twentieth century. La Luz del Mundo was founded by a young Mexican visionary who emerged from an initial contact with God with a unique mission. The Apostle Aarón began to develop his church, La Luz del Mundo (The Light of the World), in Guadalajara. It followed a unique version of Arian Christianity, which recognized the one God the Father and his Son Jesus Christ, and additionally restored the office of Apostle to its primary role in church leadership. In 1960, La Luz del Mundo entered Texas, the state where Pentecostalism was receiving its greatest support. In its 60 years of life thereafter, the church has experienced a steady increase in membership year-by year. Its success in the state has been capped by the construction of a headquarters temple in Houston. KEYWORDS: La Luz del Mundo, Pentecostalism, Pentecostalism in Texas, Religion in Texas, Houston La Luz del Mundo Temple. Note: This article has emerged from a larger project devoted to the production of a history of Pentecostalism in Texas. To date, as this project has proceeded, a series of papers and one monograph have appeared (Melton 2015, 2018, 2019a, 2019b). -

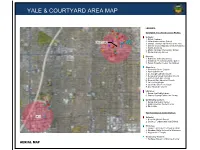

Yale Transitional Center Radius: YALE 1 Schools: 1

YALE & COURTYARD AREA MAP LEGENDS: 2 6 2 1 Courtyard Transitional Center Radius: 2 3 4 Schools: 3 1. El Sol Academy 1 8 3 2. Willard Intermediate School COURTYARD 2 4 5 3 7 3. Orange County High School of the Arts 2 9 5 4. Orange County Educational Arts Academy 5. NOVA Academy 1 1 6. Martin Heninger Elementary School 1 7. Santa Ana High School 6 7 Daycare: 1. Katherine Irvine Day School 2. Storybook Preschool & Kindergarten 3. Hands Together Center for Children Churches: 1. Sovereign Grace Church 2. Episcopal Church 3. St. Joseph Catholic Church 4. Santa Ana United Methodist Church 5. First Presbyterian Church 6. Seventh-Day Adventist Church 7. La Luz Del Mundo 8. Iglesia de Dios Pentecostal 9. Zion Apostolic Church Libraries: 1. Santa Ana Public Library 2. Orange County Public Law Library Community Centers: 2 1. Santa Ana Senior Center 1 1 2. Asian American Senior Center 2 3. Ebell Club 3 Yale Transitional Center Radius: YALE 1 Schools: 1. Kenneth Mitchell School 2. Godinez Fundamental High School Churches: 1. Gospel Light Church of God in Christ 2. Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses 3. Nguyen At V Temple Community Centers: 1. Heritage Museum of Orange County AERIAL MAP YALE TRANSITIONAL CENTER LEGENDS: Yale Transitional Center Radius: Schools : 1. Kenneth Mitchell School 2. Godinez Fundamental High School Churches: 1. Gospel Light Church of God in Christ 2. Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses 3. Nguyen At V Temple 2 Community Centers: 1. Heritage Museum of Orange County 1 1 2 3 1 AERIAL MAP COURTYARD TRANSITIONAL CENTER LEGENDS: Courtyard Transitional Center Radius: 2 Schools: 1. -

EPIPHANIA | Appear — Aparecer

EPIPHANIA | appear — aparecer “To g e t h e r W e M a k e t h e K i n g d o m a R e a l i t y” 701 North Hiatus Road ● Pembroke Pines, Florida 33026 ● Tel 954.432.0206 ● www.stmax.cc PASTORAL STAFF ● PERSONAL PASTORAL HOLY MASS ● LA SANTA MISA Pastor: Fr. Jeff McCormick Saturday Vigil: Parochial Vicar: Fr. Joseph Maalouf 5:00 pm 7:00 pm español Deacons: Rev. Mr. Carl Carieri, Rev. Mr. Scott Joiner, Sunday: Rev. Mr. Pierre Douyon, Rev. Mr. Manuel Mendoza 8:00 am 9:30 am 11:00 am 12:30 pm 6:00 pm Weekday (Monday - Saturday): PARISH OFFICE ● OFICINA PARROQUIAL 8:00 am Tel: 954.432.0206 Healing & Bereavement (4th Monday of the month): Fax: 954.432.0775 7:00 pm Email: [email protected] Website: www.stmax.cc Holy Day of Obligation: Hours: Mon - Fri: 8:00 am - 4:00 pm See bulletin and Parish website for Mass schedule Saturday: 3:00 pm - 7:00 pm Sunday: 8:00 am - 2:00 pm CONFESSION ● CONFESIÓN Saturday: FAITH & ACADEMIC FORMATION 4:00 pm - 5:00 pm or by appointment o por cita Director of Religious Education: Maryann Hotchkiss Tel 954.885.7260 · Fax 954.885.7261 · [email protected] Preschool Director: Jimena Hibbard NOVENA ● DEVOTION ● DEVOCIÓN Tel 954.885.7250 · Fax 954.885.7252 · [email protected] Director of Youth Ministry: John Mark Kaldahl Monday: 954.432.0206 · [email protected] 7:00 pm - Novena to Our Lady of Perpetual Help Saturday: 8:00 am - Novena to St. -

Toward a Classification System of Religious Groups in the Americas by Major Traditions and Family Types

LATIN AMERICAN SOCIO-RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROGRAM (PROLADES) TOWARD A CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM OF RELIGIOUS GROUPS IN THE AMERICAS BY MAJOR TRADITIONS AND FAMILY TYPES Clifton L. Holland, Editor First Edition: 30 October 1993 Last Modified on 20 April 2010 PROLADES Apartado 1524-2050, San Pedro, Costa Rica Telephone: (506) 283-8300; Fax (506) 234-7682 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.prolades.com © Clifton L. Holland 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 PROLADES Apartado 1524-2050 San José, Costa Rica All Rights Reserved 2 CONTENTS 1. Document #1: Toward a Classification System of Religious Groups in the Americas by Major Traditions and Family Types 7 2. Document #2: An Annotated Outline of the Classification System of Religious Groups by Major Traditions, Families and Sub-Families with Special Reference to the Americas 15 PART A: THE OLDER LITURGICAL CHRISTIAN TRADITIONS 15 A1.0 EASTERN LITURGICAL TRADITIONS 15 A1.10 EASTERN OTHODOX TRADITION 15 A1.11 Patriarchates 16 A1.12 Autocephalous Orthodox Churches 16 A1.13 Other Orthodox Churches in the Americas 17 A1.14 Schismatic Groups of Eastern Orthodox Origins 18 A1.20 NON-CALCEDONIAN ORTHODOX TRADITION 18 A1.21 Nestorian Family – Church of the East 18 A1.22 Monophysite Family 19 A1.23 Coptic Church Family 19 A1.30 INTRA-FAITH ORTHODOX ORGANIZATIONS 20 A2.0 WESTERN LITURGICAL TRADITION 20 A2.1 Roman Catholic Church 21 A2.2 Religious Orders of the Roman Catholic Church 21 A2.3 Autonomous Orthodox Churches in communion with the Vatican 21 A2.4 Old Catholic Church Movement 23 A2.5 Other -

Church Pg (4) 10-17

4 The Goodland Daily News / Thursday, October 17, 2002 Saints and sinners: The life of a Jehovah’s Witness This is a story of how I became a Jehovah’s ous, cheerful and happy people. At their inter- year 2000.) life. Witness for a day. national assembly in London, I was treated with george Ironically, while the doorbell ministry irri- “I can understand how you feel,” he told her. Like everybody else, I had been called on the utmost kindness, gentle courtesy and genu- tates so many, it is responsible for the Witnesses’ Then he added, “If it is any consolation, you can numerous times over the years by these door- ine friendliness by every Witness I met.” plagenz great growth. be sure it was not a Jehovah’s Witness who to-door “telemarketers,” who use the doorbell But the Witnesses’ “doorbell ministry” con- “Most who are Witnesses today once killed your son.” instead of the telephone to get your attention — tinues to annoy some. Witnesses still receive an slammed the door in the face of a Witness Witnesses believe we are living in the Last and often your goat! inhospitable reception at many doors. Having • saints & sinners caller,” Gene said. “But situations change in Days. They look forward to the “new heaven The Witnesses’ foot-in-the-door tactics an- never had a door slammed in my face, I decided people’s lives. The next time we come, they may and new earth,” spoken of in the book of Rev- tagonized many. Consequently, it was not un- to see what it was like.