Real Artists Don't Starve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. 3, Spring 2001

The University of Iowa School of ArtNEWSLETTER &History Volume 3 Spring/Summer 2001 Art Greetings Warm greetings from the School of Art and Adams, who taught contemporary African Art History! After one of the coldest and art with us this spring will be joining us from harshest winters on record here we as an assistant professor of art history this enjoyed a magnificent spring (although we fall. Over the next few weeks we expect Dorothy are all keeping an eye on the river which to add a faculty member in graphic design is getting higher every day). As the and several visitors in art and art history Johnson, spring semester draws to a close we are for the next academic year. looking forward to the M.F.A. show in the Director Museum of Art and are still enjoying the Growth & Development faculty show at the Museum which is one The School continues to grow every year. of the largest and most diverse we have The numbers of our faculty members seen. This year, thanks to the generosity increase as we try to keep up with ever- of the College, the Vice President for growing enrollments at the undergraduate Research and the University Foundation, and graduate levels. This year we have we are going to have a catalogue of the well over 700 undergraduate majors and faculty exhibit in full color. over 200 graduate students. In addition, we serve thousands of non-majors, espe- Farewells cially in our General Education classes in This is also the time of year for farewells. -

APRIL 1974 60C

APRIL 1974 60c Fi • • o ° ".,o" ShJ'mpo-West,the company that brought you the great Shl'mpo-West° RK-2 potter's wheel, nOW brings you \ ,,,, P the great ohimpo-West RK-2 potter's wheelJ Once you design a wheel like We think the competition is the RK-2, there aren't many ways it can be quite flattering. It has even spurred us on to improved upon. People havetried (believe us!) try radical new ideas and designs. But the but it's tough to come up with something that end product is always basically the same: matches its compactness, power, durability, quality construction, good engineering precision, control and quiet, trouble-free design. The RK-2. We think this is the performance. right kind of progress! SHIMPO-WEST P.O. BOX 2315, LA PUENTE, CAUFORNIA 91746 MAKE YOUR OWN KILN Save money.., add flexibility with Johnson burners Johnson has gas burners to meet all kiln sizes and tem- Simply add Johnson burners and kiln refractory as your perature requirements. They are made of rugged cast iron needs change• with heavy brass valves• They are easy to install and op- Cut your investment• Look into Johnson burners now. erate, and best of all, the cost of a "custom-made" kiln They are available in two basic types: (1) Atmospheric with Johnson burners is a small fraction of the cost of a -- recommended for small kilns and kilns with low tem- Power (blower operated) manufactured model. perature requirements; and (2) The size of your "custom-made" kiln is easy to enlarge. -

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism

Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Mary Henry Pansynclastic Riddle 1966, 48 x 61.5 Courtesy of the Artist and Bryan Ohno Gallery Cover photo: Hilda Morris in her studio 1964 Photo: Hiro Moriyasu Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism Organized by The Art Gym, Marylhurst University 12 Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington with support from the Regional Arts and Culture Council, the Lamb Foundation, members and friends. The Art Gym, Marylhurst University, Marylhurst, Oregon Kathleen Gemberling Adkison September 26 – November 20, 2004 Doris Chase Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner, Washington January 15 – April 3, 2005 Sally Haley Mary Henry Maude Kerns LaVerne Krause Hilda Morris Eunice Parsons Viola Patterson Ruth Penington Amanda Snyder Margaret Tomkins Eunice Parsons Mourning Flower 1969, collage, 26 x 13.5 Collection of the Artist Photo: Robert DiFranco Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington Copyright 2004 Marylhurst University Post Offi ce Box 261 17600 Pacifi c Highway Marylhurst, Oregon 97036 503.636.8141 www.marylhurst.edu Artworks copyrighted to the artists. Essays copyrighted to writers Lois Allan and Matthew Kangas. 2 All rights reserved. ISBN 0-914435-44-2 Design: Fancypants Design Preface Northwest Matriarchs of Modernism: Twelve presented work created prior to 1970. Most of our Proto-feminists from Oregon and Washington exhibitions either present art created specifi cally grew out of a conversation with author and for The Art Gym, or are mid-career or retrospective critic Lois Allan. As women, we share a strong surveys of artists in the thick of their careers. -

Show of Hands

Show of Hands Northwest Women Artists 1880–2010 Maria Frank Abrams Ruth Kelsey Kathleen Gemberling Adkison Alison Keogh Eliza Barchus Maude Kerns Harriet Foster Beecher Sheila Klein Ross Palmer Beecher Gwendolyn Knight Susan Bennerstrom Margot Quan Knight Marsha Burns Margie Livingston Margaret Camfferman Helen Loggie Emily M. Carr Blanche Morgan Losey Lauri Chambers Sherry Markovitz Doris Chase Agnes Martin Diem Chau Ella McBride Elizabeth Colborne Lucinda Parker Show of Hands Northwest Women Artists 1880–2010 Claire Cowie Viola Patterson Louise Crow Mary Ann Peters Imogen Cunningham Susan Point Barbara Matilsky Marita Dingus Mary Randlett Caryn Friedlander Ebba Rapp Anna Gellenbeck Susan Robb Virna Haffer Elizabeth Sandvig Sally Haley Norie Sato Victoria Haven Barbara Sternberger Zama Vanessa Helder Maki Tamura Karin Helmich Barbara Earl Thomas Mary Henry Margaret Tomkins Abby Williams Hill Gail Tremblay Anne Hirondelle Patti Warashina Yvonne Twining Humber Marie Watt Elizabeth Jameson Myra Albert Wiggins Fay Jones Ellen Ziegler Helmi Dagmar Juvonen whatcom museum, bellingham, wa contents This book is published in conjunction with the 6 Foreword exhibition Show of Hands: Northwest Women Artists 1880–2010, organized by the Whatcom Patricia Leach Museum and on view from April 24–August 8, 2010. Funding for the exhibition and the 8 Acknowledgments accompanying catalogue was supported in part with funds provided by the Western 10 A Gathering of Women States Arts Federation (WESTAF) and the Barbara Matilsky National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). The City of Bellingham also generously funded the 52 Checklist of the Exhibition catalogue. Additional support was provided by the Washington Art Consortium (WAC). Published in the United States by 55 Bibliography Whatcom Museum 56 Photographic Credits © 2010 by the Whatcom Museum 121 Prospect Street Bellingham, WA 98225 The copyright of works of art reproduced in www.whatcommuseum.org 56 Lenders to the Exhibition this catalogue is retained by the artists, their heirs, successors, and assignees. -

Eugene Meetings (August 16-19)-Page 485

Eugene Meetings (August 16-19)-Page 485 Notices of the American Mathematical Society August 1984, Issue 235 Volume 31, Number 5, Pages 433-560 Providence, Rhode Island USA ISSN 0002-9920 Calendar of AMS Meetings THIS CALENDAR lists all meetings which have been approved by the Council prior to the date this issue of the Notices was sent to press. The summer and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Association of America and the Ameri· can Mathematical Society. The meeting dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have yet been assigned. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated below. First and second announcements of the meetings will have appeared in earlier issues. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS presented at a meeting of the Society are published in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices which contains the program of the meet ing. Abstracts should be submitted on special forms which are available in many departments of mathematics and from the office of the Society in Providence. Abstracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the deadline for ab stracts submitted for consideration for presentation at special sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For additional information consult the meeting announcement and the list of organizers of special sessions. -

Olaf Berulfson Vrålstad Family History (PDF)

OLAF BÆRULFSON VRÅLSTAD FAMILY HISTORY Written by Gerhard A. Naeseth Published 1978 (May 1, 2009 update) OCTOBER, 1999,REVISORS NOTES: All the data under Tor Olsen Vrålstad (A5) and Ingeborg Olsdatter Vrålstad (A7) has been entered since the original 1978 edition. Considerable data under Ole Jørgenson Berulson (A4E) as well as minor updates throughout have also been added since the original edition. The Asberg Johanne Ellingsdatter Naas Family, numbered (x) in the original edition has been renumbered (BB). Table of Contents Olaf Bærulfson Vrålstad (A) 1780-1825 Jørgen Olsen Vrålstad (A1) 1808- Ole Olsen Wrolstad (A2) 1810-1884 Ole Olsen Wrolstad (A2A) 1836-1911 John Olsen Wrolstad (A2B) 1839-1907 Jørgen (George) Olsen Wrolstad (A2C) 1842-1899 Halvor Olsen Wrolstad (A2D) 1847-1935 Hans Olsen Wrolstad (A2E) 1849-1880 Martin Olsen Wrolstad (A2F) 1852-1853 Martin Olsen Wrolstad (A2G) 1856-1919 Jørgen Olsen Vrålstad (A3) 1812- Marthe Jørgensdatr. (A3A) 1841- Ole Jørgensen (A3B) 1842-1866 Gunhild Oline Jørgensdatr. (A3C) 1844-1845 Gunhild Oline Jørgensdatr. (A3D) 1846- Thor Jørgensen (A3E) 1848-1866 Ole Jørgensen (A3F) 1850-1851 Ole Jørgensen (Graves)(A3G) 1852-1915 Anne Birgithe Jørgensdatr (A3H) 1854- Ingeborg Torine Jørgensdatr.(A3I) 1856 Kari Thomine Jørgensdatr. (A3J) 1858- Torberg Ellevine Jørgensdatr.(A3K) 1860- Aaste Tolvine Jørgensdatr. (A3L) 1862-1864 Aaste Tolvine Jørgensdatr. (A3M) 1864- Thorine Olette Jørgensdatr. (A3N) 1867 Bæruld Olsen Wrolstad (A4) 1815-1858 Ole Bæruldsen Wrolstad (A4A) 1843-1846 Marte Thorine Bæruldsdatter Wrolstad (A4B) 1845-1873 Knud Olaus Berulfsen Wrolstad (A4C) 1851-1933 Siri Oline Bæruldsdatter Wrolstad (A4D) 1854-1944 Ole Jørgensen Berulson (A4E) 1857-1931 Thor Olsen Vrålstad (A5) 1818- Marte Oline Thorsdatr. -

Preview of the Visual Arts | April–May 2008

www.preview-art.com THE GALLERY GUIDE ALBERTA ■ BRITISH COLUMBIA ■ OREGON ■ WASHINGTON April/May 2008 SNAP CONTEMPORARY ART 190 West 3rd Ave., Vancouver, BC 604-879-7627 www.snapart.ca a new look for art on the Web contact subscribe search listings THE GALLERY GUIDE ALBERTA BRITISH COLUMBIA OREGON WASHINGTON GO CALENDAR PREVIEWS GALLERY WEBSITES find www.preview-art.com CONSERVATION CORNER SearchSearch forfor gallery,artwork artist, medium... 8 PREVIEW ■ APRIL/MAY 2008 COVER: Jan Crawford, Nightfall (2007), acrylic on canvas [Linda Lando Fine Art, Vancouver BC, Apr 24-May 3] previews Vol. 22 No. 2 ALBERTA 12 Lynn Richardson:Inter-Glacial Free 10 Calgary Trade agency.ca 14 Edmonton 16 Lethbridge Diana Burgoyne:Sound Drawings 18 Medicine Hat, Red Deer 12 Art Gallery of Calgary BRITISH COLUMBIA 14 Dorothy Knowles 18 Burnaby Douglas Udell Gallery, Edmonton 20 Campbell River, Chilliwack 21 Coquitlam, Courtenay 18 Jan Crawford & Sue Heatherington 22 Delta, Fort Langley, Gabriola Island Linda Lando Fine Art 23 Galiano Island, Grand Forks, Kamloops 38 34 Elspeth Pratt 25 Kaslo, Kelowna Charles H. Scott Gallery 26 Maple Ridge, Nanaimo, Nanoose Bay 38 Vessna Perunovich 27 Nelson, New Westminster, The Stride Gallery North Vancouver 29 Osoyoos, Parksville, Penticton 50 John Franklin Koenig:Northwest Master 30 Port Moody, Prince George, 56 Whatcom Museum Prince Rupert 31 Quadra Island, Qualicum Beach, 54 Stephen Waddell Richmond Contemporary Art Gallery 32 Salmon Arm, Salt Spring Island 56 Gary Pearson:The End is My Beginning 33 Sidney, Sidney-North -

ERITAGE Ustainin G

S ustaining Our Heritage The IMLS Achievement ustaining S H Our eritage The IMLS Achievement Dear Colleague, ear Friends, At part of its celebration of the 25th anniversary of the Museum Services I’m delighted to recognize the 25th anniversary of the Act, IMLS is publishing Sustaining Our Heritage: The IMLS Achievement. This is the story of the agency’s long-standing commitment to the Museum Services Act, and the commemoration of that conservation of museum collections. Throughout 17 years of steady and anniversary through the publication of Sustaining Our unwavering support the Institute of Museum and Library Services, in D partnership with American museums, has profoundly improved the care Heritage: the IMLS Achievement. Through the years the of museum collections. These collections tell the epic story of human Institute of Museum and Library Services has been a experience; the legacy of this partnership is that future generations will use and learn from these treasures for years to come. catalyst for excellence and outreach for all Americans. I would like to recognize several individuals whose dedication and Museums of all types, from art and history to science inspiration have been key to this achievement. We are grateful to past directors of the Institute and chairs of the National Museum Services museums and zoos, play an important role in preserving Board, especially Susan Phillips, Lois Burke Sheppard, Peter Raven and our natural and cultural heritage. Many of us remember Willard L. Boyd who were in leadership posts as the conservation focus developed. Much of the credit also goes to the staff of IMLS: Mary the first trips we took to such places. -

1984 Mathematical Sciences Professional Directory

Notices of the American Mathematical Society April 1984, Issue 233 Volume 31, Number 3, Pages 241-360 Providence, Rhode Island USA ISSN 0002-9920 Calendar of AMS Meetings THIS CALENDAR lists all meetings which have been approved by the Council prior to the date this issue of the Notices was sent to press. The summer and annual meetings are joint meetings of the Mathematical Association of America and the Ameri· can Mathematical Society. The meeting dates which fall rather far in the future are subject to change; this is particularly true of meetings to which no numbers have yet been assigned. Programs of the meetings will appear in the issues indicated below. First and second announcements of the meetings will have appeared in earlier issues. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS presented at a meeting of the Society are published in the journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American Mathematical Society in the issue corresponding to that of the Notices which contains the program of the meet· ing. Abstracts should be submitted on special forms which are available in many departments of mathematics and from the office of the Society in Providence. Abstracts of papers to be presented at the meeting must be received at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Island, on or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the deadline for ab· stracts submitted for consideration for presentation at special sessions is usually three weeks earlier than that specified below. For additional information consult the meeting announcement and the list of organizers of special sessions. -

Oregon's Digital Collections: Environmental Scan 1 of 225 Dcplumer Associates, Sept

OREGON’S DIGITAL COLLECTIONS PART I: ENVIRONMENTAL SCAN OF EXISTING PROJECTS AND MODELS FOR STATEWIDE COLLABORATION PREPARED FOR: OREGON STATE LIBRARY LIBRARY DEVELOPMENT SERVICES 250 WINTER ST. NE SALEM, OREGON 97301-3950 PREPARED BY: DANIELLE CUNNIFF PLUMER, PH.D., M.S.I.S. DCPLUMER ASSOCIATES, L.L.C. 4500 WILLIAMS DR., SUITE 212-414 GEORGETOWN, TX 78633 WWW.DCPLUMER.COM SEPTEMBER 25, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose and Background ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Note on Terminology ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Oregon Library Systems and Technology Act Five-Year Plan ............................................................................ 4 Goal #1: Provide access to information resources and library services ......................................................................... 5 Goal #2: Use technology to increase capacity to provide library services and expand access ......................................... 6 Goal #3: Develop a culture in libraries -

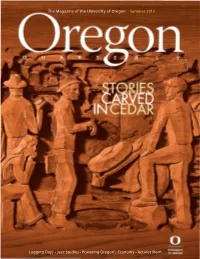

The Magazine of the University of Oregon Summer 2013 Logging

The Magazine of the University of Oregon Summer 2013 Logging Days • Jazz Studies • Powering Oregon’s Economy • Activist Mom 0201S King Eltal'll Winery I Pleue Drink Reaponllbly www.kingestate.com The Magazine of the University of Oregon Summer 2013 • Volume 92 Number 4 28 The Language of Logging OregonQuarterly.com FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 28 2 EDITOR’S NOTE LOGGING DAYS 4 LETTERS By Daniel Lindley, MS ’93 10 UPFRONT | Excerpts, Exhibits, The winner of our 14th annual Explorations, Ephemera Northwest Perspectives Essay Contest tells how a self-described tree hugger Beat the Clock Art of the Depression came to understand loggers. By Lauren Kessler 32 Cowboy Up 32 By Jesse Ellison, JD ’05 Powering Oregon’s STORIES CARVED IN CEDAR Economy By Kenneth O’Connell ’66, MFA ’72 Bookshelf Six Depression-era murals by master woodcarver Art Clough depict the 18 UPFRONT | News, Notables, grandeur of Oregon’s landscape, the Innovations tenacious spirit of its people, and Nota Bene a dark underside rarely seen in the government-sponsored art of the day. Test Kitchen 38 Actively Parenting Passing the Baton 38 Around the Block The Best . Place to Enjoy SIDEWALK OR STREET? the Fruits of Summer By Mary DeMocker ’92 In Brief A Eugene mother weighs the risks PROFile: Alexander B. of activism she sees as critical to Murphy her children’s future against her commitment to be present for OLD OREGON them in the here and now. 50 Marching to His Own Beat Fruits of Their Labor Jazz Masters 44 44 A Life Telling Stories OREGON JAZZ COVER | Detail from one of master woodcarver Class Notes Art Clough's Depression-era cedar panels that By Brett Campbell, MS ’96 Decades hang in Knight Library. -

Carl Hall Gallery

COLLECTION GUIDE Carl Hall Gallery Hallie Ford Museum ofArt1 On the Edge PACIFIC NORTHWEST ART FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST COLLECTION at the Hallie Ford Museum of Art includes paintings, sculptures, and works on paper created by Oregon artists as well as modern and contemporary works from Washington, Idaho, and Montana. Northwest art has been central to the mission of the Hallie Ford Museum of Art since it was first envisioned in the early 1990s. A long tradition of art instruction at Willamette, beginning in the 1850s and continuing with today’s strong departments of art and art history, provides the context for making regional art one of the primary emphases of this university-linked museum. Selections from the Pacific Northwest collection are exhibited in the Carl Hall Gallery, named for the painter who came to Oregon for basic training during World War II and, following his service in the Pacific, returned to the state he referred to as “Eden again.” He taught painting, drawing, and printmaking at Willamette University for thirty-eight years, retiring in 1986. Although the permanent collection contains some nineteenth-century Oregon art, the Carl Hall Gallery presents Northwest art from the 1930s to the twenty-first century. The title of the installation, On the Edge: Pacific Northwest Art from the Permanent Collection, recognizes the edgy, avant-garde nature of these works within their respective periods—as well as the region’s location on the edge of the continent. The Pacific Northwest collection is made up of works purchased with the Maribeth Collins Art Acquisition Fund and also includes donations of individual works from artists as well as collectors, such as Dan and Nancy Schneider.