Faults and Joints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strike and Dip Refer to the Orientation Or Attitude of a Geologic Feature. The

Name__________________________________ 89.325 – Geology for Engineers Faults, Folds, Outcrop Patterns and Geologic Maps I. Properties of Earth Materials When rocks are subjected to differential stress the resulting build-up in strain can cause deformation. Depending on the material properties the result can either be elastic deformation which can ultimately lead to the breaking of the rock material (faults) or ductile deformation which can lead to the development of folds. In this exercise we will look at the various types of deformation and how geologists use geologic maps to understand this deformation. II. Strike and Dip Strike and dip refer to the orientation or attitude of a geologic feature. The strike line of a bed, fault, or other planar feature, is a line representing the intersection of that feature with a horizontal plane. On a geologic map, this is represented with a short straight line segment oriented parallel to the strike line. Strike (or strike angle) can be given as either a quadrant compass bearing of the strike line (N25°E for example) or in terms of east or west of true north or south, a single three digit number representing the azimuth, where the lower number is usually given (where the example of N25°E would simply be 025), or the azimuth number followed by the degree sign (example of N25°E would be 025°). The dip gives the steepest angle of descent of a tilted bed or feature relative to a horizontal plane, and is given by the number (0°-90°) as well as a letter (N, S, E, W) with rough direction in which the bed is dipping. -

Introduction San Andreas Fault: an Overview

Introduction This volume is a general geology field guide to the San Andreas Fault in the San Francisco Bay Area. The first section provides a brief overview of the San Andreas Fault in context to regional California geology, the Bay Area, and earthquake history with emphasis of the section of the fault that ruptured in the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. This first section also contains information useful for discussion and making field observations associated with fault- related landforms, landslides and mass-wasting features, and the plant ecology in the study region. The second section contains field trips and recommended hikes on public lands in the Santa Cruz Mountains, along the San Mateo Coast, and at Point Reyes National Seashore. These trips provide access to the San Andreas Fault and associated faults, and to significant rock exposures and landforms in the vicinity. Note that more stops are provided in each of the sections than might be possible to visit in a day. The extra material is intended to provide optional choices to visit in a region with a wealth of natural resources, and to support discussions and provide information about additional field exploration in the Santa Cruz Mountains region. An early version of the guidebook was used in conjunction with the Pacific SEPM 2004 Fall Field Trip. Selected references provide a more technical and exhaustive overview of the fault system and geology in this field area; for instance, see USGS Professional Paper 1550-E (Wells, 2004). San Andreas Fault: An Overview The catastrophe caused by the 1906 earthquake in the San Francisco region started the study of earthquakes and California geology in earnest. -

Significance of Brittle Deformation in the Footwall

Journal of Structural Geology 64 (2014) 79e98 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Structural Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jsg Significance of brittle deformation in the footwall of the Alpine Fault, New Zealand: Smithy Creek Fault zone J.-E. Lund Snee a,*,1, V.G. Toy a, K. Gessner b a Geology Department, University of Otago, PO Box 56, Dunedin 9016, New Zealand b Western Australian Geothermal Centre of Excellence, The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia article info abstract Article history: The Smithy Creek Fault represents a rare exposure of a brittle fault zone within Australian Plate rocks that Received 28 January 2013 constitute the footwall of the Alpine Fault zone in Westland, New Zealand. Outcrop mapping and Received in revised form paleostress analysis of the Smithy Creek Fault were conducted to characterize deformation and miner- 22 May 2013 alization in the footwall of the nearby Alpine Fault, and the timing of these processes relative to the Accepted 4 June 2013 modern tectonic regime. While unfavorably oriented, the dextral oblique Smithy Creek thrust has Available online 18 June 2013 kinematics compatible with slip in the current stress regime and offsets a basement unconformity beneath Holocene glaciofluvial sediments. A greater than 100 m wide damage zone and more than 8 m Keywords: Fault zone wide, extensively fractured fault core are consistent with total displacement on the kilometer scale. e Fluid flow Based on our observations we propose that an asymmetric damage zone containing quartz carbonate Hydrofracture echloriteeepidote veins is focused in the footwall. -

Lesson 3 Forces That Build the Land Main Idea

Lesson 3 Forces That Build the Land Main Idea Many landforms result from changes and movements in Earth’s crust. Objectives Identify types of landforms and the processes that form them. Describe what happens when an earthquake occurs. Vocabulary fault focus aftershock seismic wave epicenter seismograph magnitude vent What forces change Earth’s crust? At transform boundaries, the pieces of rock rub together in a force called shearing, like the blades of a pair of scissors, causing the rock to break. At convergent boundaries, plates collide and this force is called compression, squeezing the rock together. At divergent boundaries, plates separate causing tension, making the crust longer and thinner eventually breaking and creating a fault. Faults are usually located along the boundaries between tectonic plates. Three Kinds of Faults Shearing forms strike-slip faults. Tension forms normal faults. The rock above the fault moves down. Compression forms reverse faults. The rock above the fault moves up. Uplifted Landforms Folded mountains are mostly made up of rock layers folded by being squeezed together. Fault-block mountains are made by huge, tilted blocks of rock separated from the surrounding rock by faults. The Colorado Plateau was formed when rock layers were pushed upward. The Colorado River eventually formed the Grand Canyon. Quick Check Infer Why are faults often produced along plate boundaries? Forces act on the crust most directly at plate boundaries, because these locations are where plates are moving, relative to each other. Critical Thinking Why do some mountains form as folded mountains and others form as fault-block mountains? Compression forces form folded mountains, and tension forms fault- block mountains. -

Part 3: Normal Faults and Extensional Tectonics

12.113 Structural Geology Part 3: Normal faults and extensional tectonics Fall 2005 Contents 1 Reading assignment 1 2 Growth strata 1 3 Models of extensional faults 2 3.1 Listric faults . 2 3.2 Planar, rotating fault arrays . 2 3.3 Stratigraphic signature of normal faults and extension . 2 3.4 Core complexes . 6 4 Slides 7 1 Reading assignment Read Chapter 5. 2 Growth strata Although not particular to normal faults, relative uplift and subsidence on either side of a surface breaking fault leads to predictable patterns of erosion and sedi mentation. Sediments will fill the available space created by slip on a fault. Not only do the characteristic patterns of stratal thickening or thinning tell you about the 1 Figure 1: Model for a simple, planar fault style of faulting, but by dating the sediments, you can tell the age of the fault (since sediments were deposited during faulting) as well as the slip rates on the fault. 3 Models of extensional faults The simplest model of a normal fault is a planar fault that does not change its dip with depth. Such a fault does not accommodate much extension. (Figure 1) 3.1 Listric faults A listric fault is a fault which shallows with depth. Compared to a simple planar model, such a fault accommodates a considerably greater amount of extension for the same amount of slip. Characteristics of listric faults are that, in order to maintain geometric compatibility, beds in the hanging wall have to rotate and dip towards the fault. Commonly, listric faults involve a number of en echelon faults that sole into a lowangle master detachment. -

The Geology of the Enosburg Area, Vermont

THE GEOLOGY OF THE ENOSBURG AREA, VERMONT By JOlIN G. DENNIS VERMONT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. DOLL, State Geologist Published by VERMONT DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT MONTPELIER, VERMONT BULLETIN No. 23 1964 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT 7 INTRODUCTION ...................... 7 Location ........................ 7 Geologic Setting .................... 9 Previous Work ..................... 10 Method of Study .................... 10 Acknowledgments .................... 10 Physiography ...................... 11 STRATIGRAPHY ...................... 12 Introduction ...................... 12 Pinnacle Formation ................... 14 Name and Distribution ................ 14 Graywacke ...................... 14 Underhill Facics ................... 16 Tibbit Hill Volcanics ................. 16 Age......................... 19 Underhill Formation ................... 19 Name and Distribution ................ 19 Fairfield Pond Member ................ 20 White Brook Member ................. 21 West Sutton Slate ................... 22 Bonsecours Facies ................... 23 Greenstones ..................... 24 Stratigraphic Relations of the Greenstones ........ 25 Cheshire Formation ................... 26 Name and Distribution ................ 26 Lithology ...................... 26 Age......................... 27 Bridgeman Hill Formation ................ 28 Name and Distribution ................ 28 Dunham Dolomite .................. 28 Rice Hill Member ................... 29 Oak Hill Slate (Parker Slate) .............. 29 Rugg Brook Dolomite (Scottsmore -

Chapter 1 -- the Place of Faults in Petroleum Traps

Sorkhabi, R.,and Y. Tsuji, 2005, The place of faults in petroleum traps, in R. Sorkhabi and Y. Tsuji, eds., Faults, fluid flow, and petroleum traps: AAPG Memoir 85, 1 p. 1 – 31. The Place of Faults in Petroleum Traps Rasoul Sorkhabi1 Technology Research Center, Japan National Oil Corporation, Chiba, Japan Yoshihiro Tsuji2 Technology Research Center, Japan National Oil Corporation, Chiba, Japan ‘‘The incompleteness of available data in most geological studies traps some geologists.’’ Orlo E. Childs in Place of tectonic concepts in geological thinking (AAPG Memoir 2, 1963, p. 1) ‘‘Although the precise role of faults has never been systematically defined, much has been written that touches on the subject. One thing is certain: we need not try to avoid them.’’ Frederick G. Clapp in The role of geologic structure in the accu mulation of petroleum (Structure of typical American oil fields II, 1929, p. 686) ABSTRACT ver since Frederick Clapp included fault structures as significant petroleum traps in his landmark paper in 1910, the myriad function of faults in petroleum E migration and accumulation in sedimentary basins has drawn increasing atten- tion. Fault analyses in petroleum traps have grown along two distinct and successive lines of thought: (1) fault closures and (2) fault-rock seals. Through most of the last century, geometric closure of fault traps and reservoir seal juxtaposition by faults were the focus of research and industrial application. These research and applications were made as structural geology developed quantitative methods for geometric and kine- matic analyses of sedimentary basins, and plate tectonics offered a unified tool to correlate faults and basins on the basis of the nature of plate boundaries to produce stress. -

Lithology and Internal Structure of the San Andreas Fault at Depth Based

1 1 Lithology and Internal Structure of the San Andreas Fault at depth based on 2 characterization of Phase 3 whole-rock core in the San Andreas Fault Observatory at 3 Depth (SAFOD) Borehole 4 By Kelly K. Bradbury1, James P. Evans1, Judith S. Chester2, Frederick M. Chester2, and David L. Kirschner3 5 1Geology Department, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84321-4505 6 2Center for Tectonophysics and Department of Geology and Geophysics, Texas A&M University, College Station, 7 Texas 77843 8 3Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, St. Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri 63108 9 10 Abstract 11 We characterize the lithology and structure of the spot core obtained in 2007 during 12 Phase 3 drilling of the San Andreas Fault Observatory at Depth (SAFOD) in order to determine 13 the composition, structure, and deformation processes of the fault zone at 3 km depth where 14 creep and microseismicity occur. A total of approximately 41 m of spot core was taken from 15 three separate sections of the borehole; the core samples consist of fractured arkosic sandstones 16 and shale west of the SAF zone (Pacific Plate) and sheared fine-grained sedimentary rocks, 17 ultrafine black fault-related rocks, and phyllosilicate-rich fault gouge within the fault zone 18 (North American Plate). The fault zone at SAFOD consists of a broad zone of variably damaged 19 rock containing localized zones of highly concentrated shear that often juxtapose distinct 20 protoliths. Two zones of serpentinite-bearing clay gouge, each meters-thick, occur at the two 21 locations of aseismic creep identified in the borehole on the basis of casing deformation. -

Faults and Joints

133 JOINTS Joints (also termed extensional fractures) are planes of separation on which no or undetectable shear displacement has taken place. The two walls of the resulting tiny opening typically remain in tight (matching) contact. Joints may result from regional tectonics (i.e. the compressive stresses in front of a mountain belt), folding (due to curvature of bedding), faulting, or internal stress release during uplift or cooling. They often form under high fluid pressure (i.e. low effective stress), perpendicular to the smallest principal stress. The aperture of a joint is the space between its two walls measured perpendicularly to the mean plane. Apertures can be open (resulting in permeability enhancement) or occluded by mineral cement (resulting in permeability reduction). A joint with a large aperture (> few mm) is a fissure. The mechanical layer thickness of the deforming rock controls joint growth. If present in sufficient number, open joints may provide adequate porosity and permeability such that an otherwise impermeable rock may become a productive fractured reservoir. In quarrying, the largest block size depends on joint frequency; abundant fractures are desirable for quarrying crushed rock and gravel. Joint sets and systems Joints are ubiquitous features of rock exposures and often form families of straight to curviplanar fractures typically perpendicular to the layer boundaries in sedimentary rocks. A set is a group of joints with similar orientation and morphology. Several sets usually occur at the same place with no apparent interaction, giving exposures a blocky or fragmented appearance. Two or more sets of joints present together in an exposure compose a joint system. -

Describe the Geometry of a Fault (1) Orientation of the Plane (Strike and Dip) (2) Slip Vector

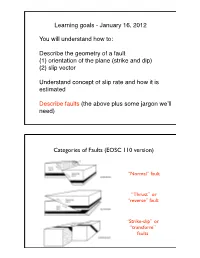

Learning goals - January 16, 2012 You will understand how to: Describe the geometry of a fault (1) orientation of the plane (strike and dip) (2) slip vector Understand concept of slip rate and how it is estimated Describe faults (the above plus some jargon weʼll need) Categories of Faults (EOSC 110 version) “Normal” fault “Thrust” or “reverse” fault “Strike-slip” or “transform” faults Two kinds of strike-slip faults Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) Stand with your feet on either side of the fault. Which side comes toward you when the fault slips? Another way to tell: stand on one side of the fault looking toward it. Which way does the block on the other side move? Right-lateral Left-lateral (dextral) (sinistral) 1992 M 7.4 Landers, California Earthquake rupture (SCEC) Describing the fault geometry: fault plane orientation How do you usually describe a plane (with lines)? In geology, we choose these two lines to be: • strike • dip strike dip • strike is the azimuth of the line where the fault plane intersects the horizontal plane. Measured clockwise from N. • dip is the angle with respect to the horizontal of the line of steepest descent (perpendic. to strike) (a ball would roll down it). strike “60°” dip “30° (to the SE)” Profile view, as often shown on block diagrams strike 30° “hanging wall” “footwall” 0° N Map view Profile view 90° W E 270° S 180° Strike? Dip? 45° 45° Map view Profile view Strike? Dip? 0° 135° Indicating direction of slip quantitatively: the slip vector footwall • let’s define the slip direction (vector) -

Present Day Plate Boundary Deformation in the Caribbean and Crustal Deformation on Southern Haiti Steeve Symithe Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 4-2016 Present day plate boundary deformation in the Caribbean and crustal deformation on southern Haiti Steeve Symithe Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Caribbean Languages and Societies Commons, Geology Commons, and the Geophysics and Seismology Commons Recommended Citation Symithe, Steeve, "Present day plate boundary deformation in the Caribbean and crustal deformation on southern Haiti" (2016). Open Access Dissertations. 715. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/715 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated ¡ ¢¡£ ¢¡¤ ¥ PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Steeve Symithe Entitled Present Day Plate Boundary Deformation in The Caribbean and Crustal Deformation On Southern Haiti. For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Is approved by the final examining committee: Christopher L. Andronicos Chair Andrew M. Freed Julie L. Elliott Ayhan Irfanoglu To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Andrew M. Freed Approved by Major Professor(s): Indrajeet Chaubey 04/21/2016 Approved by: Head of the Departmental Graduate Program Date PRESENT DAY PLATE BOUNDARY DEFORMATION IN THE CARIBBEAN AND CRUSTAL DEFORMATION ON SOUTHERN HAITI A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Steeve J. -

Composition, Alteration, and Texture of Fault-Related Rocks from Safod Core and Surface Outcrop Analogs

Pure Appl. Geophys. Ó 2014 Springer Basel DOI 10.1007/s00024-014-0896-6 Pure and Applied Geophysics Composition, Alteration, and Texture of Fault-Related Rocks from Safod Core and Surface Outcrop Analogs: Evidence for Deformation Processes and Fluid-Rock Interactions 1 1 1 1 1 KELLY K. BRADBURY, COLTER R. DAVIS, JOHN W. SHERVAIS, SUSANNE U. JANECKE, and JAMES P. EVANS Abstract—We examine the fine-scale variations in mineralogi- 1. Introduction cal composition, geochemical alteration, and texture of the fault- related rocks from the Phase 3 whole-rock core sampled between 3,187.4 and 3,301.4 m measured depth within the San Andreas Fault Well-constrained geological, geochemical, and Observatory at Depth (SAFOD) borehole near Parkfield, California. geophysical models of active fault zones are needed if This work provides insight into the physical and chemical properties, we are to understand fault zone behavior and earth- structural architecture, and fluid-rock interactions associated with the actively deforming traces of the San Andreas Fault zone at depth. quake deformation, constraining the factors that affect Exhumed outcrops within the SAF system comprised of serpentinite- the distribution of earthquakes, and the nature of slip bearing protolith are examined for comparison at San Simeon, Goat in the shallow crust by developing realistic models of Rock State Park, and Nelson Creek, California. In the Phase 3 SAFOD drillcore samples, the fault-related rocks consist of multiple subsurface fault zone structure and ground motion juxtaposed lenses of sheared, foliated siltstone and shale with block- predictions. Earthquakes nucleate in rocks at depth in-matrix fabric, black cataclasite to ultracataclasite, and sheared (e.g., FAGERENG and TOY 2011;SIBSON 1977; 2003), serpentinite-bearing, finely foliated fault gouge.