The Conference the Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020)

Nepal Human Rights Year Book 2021 (ENGLISH EDITION) (This Report Covers the Period - January to December 2020) Editor-In-Chief Shree Ram Bajagain Editor Aarya Adhikari Editorial Team Govinda Prasad Tripathee Ramesh Prasad Timalsina Data Analyst Anuj KC Cover/Graphic Designer Gita Mali For Human Rights and Social Justice Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) Nagarjun Municipality-10, Syuchatar, Kathmandu POBox : 2726, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: +977-1-5218770 Fax:+977-1-5218251 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.insec.org.np; www.inseconline.org All materials published in this book may be used with due acknowledgement. First Edition 1000 Copies February 19, 2021 © Informal Sector Service Centre (INSEC) ISBN: 978-9937-9239-5-8 Printed at Dream Graphic Press Kathmandu Contents Acknowledgement Acronyms and Abbreviations Foreword CHAPTERS Chapter 1 Situation of Human Rights in 2020: Overall Assessment Accountability Towards Commitment 1 Review of the Social and Political Issues Raised in the Last 29 Years of Nepal Human Rights Year Book 25 Chapter 2 State and Human Rights Chapter 2.1 Judiciary 37 Chapter 2.2 Executive 47 Chapter 2.3 Legislature 57 Chapter 3 Study Report 3.1 Status of Implementation of the Labor Act at Tea Gardens of Province 1 69 3.2 Witchcraft, an Evil Practice: Continuation of Violence against Women 73 3.3 Natural Disasters in Sindhupalchok and Their Effects on Economic and Social Rights 78 3.4 Problems and Challenges of Sugarcane Farmers 82 3.5 Child Marriage and Violations of Child Rights in Karnali Province 88 36 Socio-economic -

NEPAL: Preparing the Secondary Towns Integrated Urban

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 36188 November 2008 NEPAL: Preparing the Secondary Towns Integrated Urban Environmental Improvement Project (Financed by the: Japan Special Fund and the Netherlands Trust Fund for the Water Financing Partnership Facility) Prepared by: Padeco Co. Ltd. in association with Metcon Consultants, Nepal Tokyo, Japan For Department of Urban Development and Building Construction This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. TA 7182-NEP PREPARING THE SECONDARY TOWNS INTEGRATED URBAN ENVIRONMENTAL IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Volume 1: MAIN REPORT in association with KNOWLEDGE SUMMARY 1 The Government and the Asian Development Bank agreed to prepare the Secondary Towns Integrated Urban Environmental Improvement Project (STIUEIP). They agreed that STIUEIP should support the goal of improved quality of life and higher economic growth in secondary towns of Nepal. The outcome of the project preparation work is a report in 19 volumes. 2 This first volume explains the rationale for the project and the selection of three towns for the project. The rationale for STIUEIP is the rapid growth of towns outside the Kathmandu valley, the service deficiencies in these towns, the deteriorating environment in them, especially the larger urban ones, the importance of urban centers to promote development in the regions of Nepal, and the Government’s commitments to devolution and inclusive development. 3 STIUEIP will support the objectives of the National Urban Policy: to develop regional economic centres, to create clean, safe and developed urban environments, and to improve urban management capacity. -

BIRATNAGAR, 18–20 March 2014 Prepared by ADB Consultant Team

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 44140 Date: March 2014 TA 7566-REG: Strengthening and Use of Country Safeguard Systems Subproject: Strengthening Involuntary Resettlement Safeguard Systems (Nepal) CAPACITY ENHANCEMENT TRAINING ON SOCIAL SAFEGUARDS SYSTEM BIRATNAGAR, 18–20 March 2014 Prepared by ADB Consultant Team This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. Training Report Capacity Enhancement Training On Social Safeguards System. 18-20 March 201 Biratnagar TA 7566 REG: Strengthening and Use of Country Safeguards System. NEP Subproject: Strengthening Involuntary Resettlement Safeguard Systems in Nepal niri CET Report Biratnagar 18-20-3-014 – Table of Contents 1 Background: ............................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Objectives of the training ................................................................................................................... 4 1.2. Training Schedule: .............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Commencement of the training ................................................................................................................ 4 2.1.Output of the day: ............................................................................................................................. -

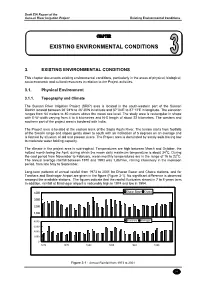

Existing Environmental Conditions

Draft EIA Report of the Sunsari River Irrigation Project Existing Environmental Conditions CHAPTER EXISTING ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS 3. EXISTING ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS This chapter documents existing environmental conditions, particularly in the areas of physical, biological, socio-economic and cultural resources in relation to the Project activities. 3.1. Physical Environment 3.1.1. Topography and Climate The Sunsari River Irrigation Project (SRIP) area is located in the south-western part of the Sunsari District located between 26°24′N to 26°30′N in latitude and 87°04′E to 87°12′E in longitude. The elevation ranges from 64 meters to 80 meters above the mean sea level. The study area is rectangular in shape with E-W width varying from 4 to 8 kilometres and N-S length of about 22 kilometres. The western and southern part of the project area is bordered with India. The Project area is located at the eastern bank of the Sapta Koshi River. The terrain starts from foothills of the Siwalik range and slopes gently down to south with an inclination of 5 degrees on an average and is formed by alluvium of old and present rivers. The Project area is dominated by sandy soils having low to moderate water holding capacity. The climate in the project area is sub-tropical. Temperatures are high between March and October, the hottest month being the April, during which the mean daily maximum temperature is about 340C. During the cool period from November to February, mean monthly temperatures are in the range of 16 to 220C. The annual average rainfall between 1970 and 1993 was 1,867mm, raining intensively in the monsoon period, from late May to September. -

FINAL REPORT.Pdf

Government of Nepal Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Ilam Municipality Ilam Preparation of GIS based Digital Base Urban Map Upgrade of Ilam Municipality, Ilam Final Report Submitted By: JV Grid Consultant Pvt. Ltd, Galaxy Pvt. Ltd and ECN Consultancy Pvt. Ltd June 2017 Government of Nepal Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Ilam Municipality Ilam Preparation of GIS based Digital Base Urban Map Upgrade of Ilam Municipality, Ilam Final Report MUNICIPALITY PROFILE Submitted By: JV Grid Consultant Pvt. Ltd, Galaxy Pvt. Ltd and ECN Consultancy Pvt. Ltd June 2017 Table of Content Contents Page No. CHAPTER - I ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 NAMING AND ORIGIN............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 LOCATION.............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.3 SETTLEMENTS AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS ......................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER - II.................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 PHYSIOGRAPHY......................................................................................................................................4 2.2 GEOLOGY/GEOMORPHOLOGY -

Biratnagar Airport

BIRATNAGAR AIRPORT Brief Description Biratnagar Airport is located at north of Biratnagar Bazaar, Morang District of Province No. 1. and serves as a hub airport. This airport is the first certified aerodrome among domestic / Hub airports of Nepal and second after Tribhuvan International Airport. This airport is considered as the second busiest domestic airport in terms of passengers' movement after Pokhara airport. General Information Name BIRATNAGAR Location Indicator VNVT IATA Code BIR Aerodrome Reference Code 3C Aerodrome Reference Point 262903 N/0871552 E Province/District 1(One)/Morang Distance and Direction from City 5 Km North West Elevation 74.972 m. /245.94 ft. Off: 977-21461424 Tower: 977-21461641 Contact Fax: 977-21460155 AFS: VNVTYDYX E-mail: [email protected] Night Operation Facilities Available 16th Feb to 15th Nov 0600LT-1845LT Operation Hours 16th Nov to 15th Feb 0630LT-1800LT Status In Operation Year of Start of Operation 6 July, 1958 Serviceability All Weather Land Approx. 773698.99 m2 Re-fueling Facility Yes, by Nepal Oil Corporation Service Control Service Instrumental Flight Rule(IFR) Type of Traffic Permitted Visual Flight Rule (VFR) ATR72, CRJ200/700, DHC8, MA60, ATR42, JS-41, B190, Type of Aircraft D228, DHC6, L410, Y12 Buddha Air, Yeti Airlines, Shree Airlines, Nepal Airlines, Schedule Operating Airlines Saurya Airlines Schedule Connectivity Tumlingtar, Bhojpur, Kathmandu RFF Category V Infrastructure Condition Airside Runway Type of surface Bituminous Paved (Asphalt Concrete) Runway Dimension 1500 -

District Transport Master Plan (DTMP)

Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, Morang February 2013 Prepared by the District Technical Office (DTO) for Morang with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR), Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID i FOREWORD It is my great pleasure to introduce this District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) of Morang district especially for district road core network (DRCN). I believe that this document will be helpful in backstopping to Rural Transport Infrastructure Sector Wide Approach (RTI SWAp) through sustainable planning, resources mobilization, implementation and monitoring of the rural road sub-sector development. The document is anticipated to generate substantial employment opportunities for rural people through increased and reliable accessibility in on- farm and off-farm livelihood diversification, commercialization and industrialization of agriculture sector. In this context, rural road sector will play a fundamental role to strengthen and promote overall economic growth of this district through established and improved year round transport services reinforcing intra and inter-district linkages . Therefore, it is most crucial in executing rural road networks in a planned way as per the District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) by considering the framework of available resources in DDC comprising both internal and external sources. Viewing these aspects, DDC Morang has prepared the DTMP by focusing most of the available resources into upgrading and maintenance of the existing road networks. This document is also been assumed to be helpful to show the district road situations to the donor agencies through central government towards generating needy resources through basket fund approach. -

UGDP: ETP) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized

Social Management Framework for Urban Governance and Development Program: Public Disclosure Authorized Emerging Towns Project (UGDP: ETP) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized <Prepared'6y : ~oject Coordination Office ([)epartment ofVr6an ([)eveCopment aM(BuU4i:no Construction !Ministry ofCl'liysicaC(J'{annino aMWo~ Public Disclosure Authorized (Ba6armalia~ %epaC July, 2011 Foreword The Social Management Framework (SMF) was prepared for the Nepal Urban Governance and Development Program: Emerging Town Project (UGDP: ETP) to be implemented by the six municipalities: ltahari, Mehchinagar, Dhankuta, Lekhnath, Baglung and Tansen. The program is being implemented by MLD, Department of Urban Development and Building Construction (DUDBC), Town Development Fund (TDF) and the municipalities under the financial support from the World Bank and the technical support from GIZI SlTNAG program. The SMF was prepared with the participation of all the above agencies and departments, who deserve special thanks for their support and cooperation. I would also like to convey my gratitude to the UGDP: ETP and WB Team members, who were always willing and available to assist in conceptualizing the study framework and approach, developing research tools, accessing relevant documents, and providing helpful insights about different issues and thematic areas that needed to be covered under the study. I am particularly thankful to Mr. Hari Prasad Bhattarai, Associate Professor of Anthropology, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu who prepared this document. My special thanks are also due to Mr. Puma Kadariya, Secretary, MPPW, Mr. Ashok Nath Upreti, Director General, DUDBC; Mr. Reshmi Raj Pandey, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Local Development; Mr. Sushi I Gyewali, Executive Director, Town Development Fund; Mr. Prakash Raghubanshi, Sr. -

Constraints Faced by the Kiwi Fruit Farmers in Ilam Municipality and Sandakpur Rural Municipality of Ilam District

Food & Agribusiness Management (FABM) 2(2) (2021) 54-61 Food & Agribusiness Management (FABM) DOI: http://doi.org/10.26480/fabm.02.2021.54.61 ISSN: 2716-6678 (Online) CODEN: FAMOCP RESEARCH ARTICLE CONSTRAINTS FACED BY THE KIWI FRUIT FARMERS IN ILAM MUNICIPALITY AND SANDAKPUR RURAL MUNICIPALITY OF ILAM DISTRICT Manisha Giria*, Ganesh Rawatb, Anup Sharmac aDepartment of horticulture, Institute of Agriculture and Animal science (IAAS), Mahendra Ratna Multiple Campus, Ilam bDepartment of horticulture, Institute of Agriculture and Animal science (IAAS), Mahendra Ratna Multiple Campus, Ilam cFaculty of Agriculture, Agriculture and Forestry University (AFU), Rampur, Chitwan *Corresponding Author e-mail: [email protected] This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT Article History: The survey research entitled “Constraints faced by Kiwi fruit farmers in Ilam Municipality and Sandakpur Rural Municipality of Ilam District” was conducted to access the problem faced by kiwi fruit farmers of Ilam Received 18 February 2021 district. For the study, 80 households were selected using simple random sampling method. 40 households Accepted 02 March 2021 each from Ilam Municipality and Sandakpur Rural Municipality were selected. The study shows that the Available online 1 March 2021 production is in slightly increasing rate in both Ilam Municipality and Sandakpur Rural Municipality. In both 6 Sandakpur and Ilam areas, 25 and 20 percent farmers are producing seedlings in their own nursery respectively and rest of seedlings requirement is met from other nursery. -

Table of Province 01, Preliminary Results, Nepal Economic Census 2018

Number of Number of Persons Engaged District and Local Unit establishments Total Male Female Taplejung District 4,653 13,225 7,337 5,888 10101PHAKTANLUNG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 539 1,178 672 506 10102MIKWAKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 269 639 419 220 10103MERINGDEN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 397 1,125 623 502 10104MAIWAKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 310 990 564 426 10105AATHARAI TRIBENI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 433 1,770 837 933 10106PHUNGLING MUNICIPALITY 1,606 4,832 3,033 1,799 10107PATHIBHARA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 398 1,067 475 592 10108SIRIJANGA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 452 1,064 378 686 10109SIDINGBA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 249 560 336 224 Sankhuwasabha District 6,037 18,913 9,996 8,917 10201BHOTKHOLA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 294 989 541 448 10202MAKALU RURAL MUNICIPALITY 437 1,317 666 651 10203SILICHONG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 401 1,255 567 688 10204CHICHILA RURAL MUNICIPALITY 199 586 292 294 10205SABHAPOKHARI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 220 751 417 334 10206KHANDABARI MUNICIPALITY 1,913 6,024 3,281 2,743 10207PANCHAKHAPAN MUNICIPALITY 590 1,732 970 762 10208CHAINAPUR MUNICIPALITY 1,034 3,204 1,742 1,462 10209MADI MUNICIPALITY 421 1,354 596 758 10210DHARMADEVI MUNICIPALITY 528 1,701 924 777 Solukhumbu District 3,506 10,073 5,175 4,898 10301 KHUMBU PASANGLHAMU RURAL MUNICIPALITY 702 1,906 904 1,002 10302MAHAKULUNG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 369 985 464 521 10303SOTANG RURAL MUNICIPALITY 265 787 421 366 10304DHUDHAKOSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 263 802 416 386 10305 THULUNG DHUDHA KOSHI RURAL MUNICIPALITY 456 1,286 652 634 10306NECHA SALYAN RURAL MUNICIPALITY 353 1,054 509 545 10307SOLU DHUDHAKUNDA MUNICIPALITY -

Best Practices on SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT of NEPALESE CITIES

Best Practices on SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT OF NEPALESE CITIES PRACTICAL ACTION NEPAL P O Box 15135, Pandol Marga,Lazimpat Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: +00 977 1 444 6015, +00 977 1 209 4063 Fax: +00 977 1 444 5995 E-mail: [email protected] Best Practices on SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT OF NEPALESE CITIES PUBLISHED BY: Practical Action Nepal P O Box 15135, Pandol Marga, Lazimpat Kathmandu, Nepal SUPPORTED BY: European Union under the EC Asia Pro Eco II programme Practical Action Nepal FIRST EDITION: November 2008 Designed & processed by WordScape, 5013567 BEST PRACTICES ON SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT OF NEPALESE CITIES Contents Abbreviations iv Foreword v 1.0 Background 1 2.0 National Best Practices in Solid Waste Management 2 Solid Waste Mangement in Bhaktapur 4 Solid Waste Management in Tribhuvannagar 9 Solid Waste Management in Bharatpur 14 Waste Management in Biratnagar 19 Solid Waste Management in Hetauda 24 NEPCEMAC involvement in door-to-door waste collection 29 Suiro programme at Bharatpur 33 Suiro Abhiyan at Hetauda Municipality 37 UEMS for household composting 41 WEPCO for Urban Environmental Protection 45 3.0 Conclusions and lessons learnt 49 References 52 iii BEST PRACTICES ON SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT OF NEPALESE CITIES Abbreviations BSMC Biratnagar Sub-Metropolitan CIty CBO Community-based organisation CBS Central Bureau of Statistics CKV Clean Kathmandu Valley DFID Department for International Development GO Governmental organization GTZ German Technical Cooperation INGO International non-governmental organisation ISWM Integrated -

COVID- 19 Epi Dashboard: Epi Week 21 (30/05/2021) National COVID- 19 Cases and Deaths

COVID- 19 Epi Dashboard: Epi week 21 (30/05/2021) National COVID- 19 cases and deaths 557,124 18,942 43,883 7,272 2,47 1.3 Confirmed cases Cases per million Last 7 days Total Deaths Deaths per million CFR Daily Covid-19 cases Daily COVID- 19 deaths 10000 700 600 8000 500 6000 400 4000 300 200 2000 100 Number of cases 0 0 deaths of Number Date of reporting Date of reporting Cumulative Covid-19 cases Cumulative COVID- 19 deaths 350000 8000 300000 250000 6000 200000 4000 150000 100000 2000 Number of cases 50000 0 0 of deaths Number Date of reportng Date of reporting 2 Province 1 COVID- 19 cases and deaths 57,765 11,843 6,019 838 172 1.5 Last 7 days Confirmed cases Cases per million Total Deaths Deaths per million CFR Daily Covid-19 cases Daily COVID- 19 deaths 1400 200 1200 1000 150 800 100 600 400 50 Number of cases 200 Number of deaths of Number 0 0 Date of reporting Date of reporting Cumulative Covid-19 cases Cumulative COVID- 19 deaths 70000 900 60000 800 700 50000 600 40000 500 30000 400 300 20000 200 Number of cases 10000 deaths of Number 100 0 0 Date of reporting Date of reporting 3 Province 2 COVID- 19 cases and deaths 38,233 6,254 3,078 615 101 1.6 Cases per million Last 7 days Confirmed cases Total Deaths Deaths per million CFR Daily Covid-19 cases Daily COVID- 19 deaths 800 35 700 30 600 25 500 20 400 15 300 200 10 Number of cases 5 100 deaths of Number 0 0 Date of reporting Date of reporting Cumulative Covid-19 cases Cumulative COVID- 19 deaths 45000 700 40000 600 35000 500 30000 400 25000 20000 300 15000 200 10000 100