Obesity Management and Indigenous Peoples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 10Th Annual CON-RCO Obesity Summer Boot Camp Delegates Will Receive a Certificate of Attendance

th the 10 Annual SUMMER BOOT CAMP JULY 18–26, 2015 Delta Lodge at Kananaskis, Kananaskis Village, Alberta, Canada TABLE OF coNTENTS Learning Objectives 3 Message from the Host 4 General Information 5 Daily Schedule 6 Speakers 12 Floor plan 21 Faculty Contact List 22 Trainee Contact List 23 THE OBESITY Boot CAMP HAS BEEN MADE POSSIBLE THE CANADIAN OBESITY NETWORK’S SUPPORTERS. We are extremely grateful for their help in making the boot camp possible! Alberta-Saxony Obesity Research & Training Alliance Canadian Beverage Association Canadian Institutes of Health Research Coca Cola Craving Change Dairy Farmers of Canada Ethicon Integrated Research and Treatment Center (IFB) Adiposity Diseases Natural Factors Nestle Health Science Novo Nordisk TOPS Club Inc. (Take Pounds Off Sensibly) LEARNING OBJEctIVES The overall objective of the Boot Camp is to provide participants with a sound outline of the scientific and method- ological issues around obesity research. The camp aims to cover all aspects of obesity ranging from epidemiology and public health to cell biology, energy regulation, clinical management and health policy. The Canadian Obesity Network – Réseau canadien en obésité (CON-RCO) is a broad network of over 10,000 organizations and individuals from many sectors and disciplines who are committed to stemming the tide of obesity in Canada and to reducing the mental, physical and economic burden of obesity on Canadians. The mission of CON-RCO is to act as a catalyst for addressing obesity in Canada and to foster knowledge translation, capacity building, and partnerships among stakeholders so that researchers, health professionals, policy makers and other stakeholders may develop effective solutions to treat, and to prevent obesity. -

Clinical Updates in Bariatric Surgery: What Every Clinician Needs to Know from Referral to Post-Surgery Follow-Up TIME: 08:30 AM–16:30 PM

http://www.con-obesitysummit.ca th TUESDAY, APRIL 25 , 2017 Clinical Updates in Bariatric Surgery: What Every Clinician Needs to Know from Referral to Post-Surgery Follow-up TIME: 08:30 AM–16:30 PM 1 2 2 3 Workshop Presenters: Dr. David Urbach , Karyn Mackenzie , Patti Kastanias , Dr. Wynne Lundblad , 3 4 5 6 4 4 Dr. Alexis M. Fertig , Susan Wnuk , Stephanie E. Cassin , Dr. Raed Hawa , Chau Du , Rebecca Kirsh , 7 6 8 Jennifer Brown , Lorraine Gougeon , and Dr. Sanjeev Sockalingam 1. McGill University; 2. University of Toronto Collaborative Bariatric Surgery Program; 3. University of Pittsburgh; 4. University Health Network, Toronto; 5. University of Calgary; 6. Toronto Western Hospital; 7. Ottawa Hospital Weight Management Clinic; 8. Bariatric Surgery Psychosocial Program, Toronto Western Hospital Learning Objectives: 1. Describe the role that clinicians have in pre- and post-bariatric surgery care. 2. Identify new tools and evidence for assessing and supporting bariatric surgery patients throughout the bariatric surgery process. 3. Apply medical, nutrition and psychosocial protocols and interventions that improve patient outcomes after bariatric surgery. Abstract: Bariatric surgery is recognized as an effective and durable treatment for severe obesity; however, bariatric and primary care teams require awareness and skills to manage the myriad of pre- and post-operative concerns. Pre-surgery concerns consist of bariatric surgery readiness assessment, surgical risks and psychosocial stability. Further, patients require additional assessment and intervention after surgery, including early recognition of bariatric surgery complications and evidence-informed psychosocial interventions to maintain weight loss and health benefits long-term. This full-day workshop will provide participants with an integrated interprofessional approach to bariatric surgery assessment and aftercare. -

Canadian Obesity Student Meeting June 18 - 21, 2014

th Canadian Obesity Student Meeting June 18 - 21, 2014 #COSM2014 4 University of Waterloo - Waterloo, ON, Canada 1 Organizing Committee: Canadian Obesity Network: CON -SNP UW Dr. Arya Sharma Taryn Orava (Co-Chair) Dawn Hatanaka Cassandra Lowe (Co-Chair) Brad Hussey Iris Levine (Kinesiology Representative) Jessica Lieffers (COSM Logistics Coordinator) CON-SNP National Executive Rachel Laxer (PICDP Liaison) Angela Alberga (Chair) Cassondra McCrory (Guest Speaker & Session Coordinator) Keith Brewster (Vice Chair) Isabelle Messa (Communications Director) Cassandra Lowe (Events & Recruitment Coordinator) Jill Morrison (Program Development) Jasmin Bhawra (Secretary) Gobi Sriranganathan (Fundraising Coordinator) Deborah Schwartz (Financial Director) Renata Valaitis (Social Events Coordinator) Paul Gorczynski (Communications Director) Lana Vanderlee (PICDP Liaison) Stacy Dikareva (Chapter representative (East)) Corrie Vincent (Social Events & Volunteer Coordinator) Sarah Chapelsky (Chapter representative (West)) Jessica Lieffers (CON Scientific Committee Liaison) Advisory Panel: Samantha Hajna (Outgoing Chair) Dr. Rhona Hanning (University of Waterloo) Taryn Orava (Outgoing Vice Chair) Dr. Barbara Riley (Propel Centre for Population Health Impact) Darla Steinmann (Propel Centre for Population Health Impact) Dr. Arya Sharma (CON-RCO) - 2 - Table of Contents Schedule-at-a-Glance 4 Messages From the Organizers 6 From the Advisory Panel 7 From CON-SNP National 8 General Information 9 Maps University of Waterloo Main Campus 10 Buildings at St. Paul’s University College 11 Running Routes (2.5 km & 10 km) 11 Uptown Waterloo/Restaurant Guide 13 Daily Schedules Wednesday June 18, 2014 16 Thursday June 19, 2014. 17 Friday June 20, 2014 20 Saturday June 21, 2014 22 Poster Presentations 25 Who’s Who at COSM 2014 28 Oral Presentation Abstracts 38 Poster Presentation Abstracts 54 Awards 64 The team at Watson’s Eatery is committed to healthy eating and sustainability. -

Report Card Full Version (PDF)

REPORT CARD ON ACCESS TO OBESITY TREATMENT FOR ADULTS IN CANADA 2017 REPORT CARD ON ACCESS TO OBESITY TREATMENT FOR ADULTS IN Canada 2017 Notice and Disclaimer No part of these materials may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission from the Canadian Obesity Network-Réseau canadien en obésité. This booklet is provided under the understanding and basis that none of the publisher, the authors or other persons involved in its creation shall be responsible for the accuracy or currency of the contents, or for the results of any action taken on the basis of the information contained in this book or for any errors or omissions contained herein. No reader should act on the basis of any matter contained in this booklet without obtaining appropriate professional advice. The publisher, the authors and other persons involved in this booklet disclaim liability and responsibility resulting from any ideas, products or practices mentioned in the text and disclaim all and any liability and responsibility to any person, regardless of whether such person purchased this booklet, for loss or damage due to errors and omissions in this book and in respect of anything and of the consequence of anything done or omitted to be done by such person in reliance upon the content of the booklet. Parts of this material are based on data and information provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. -

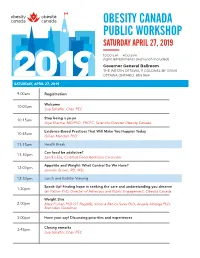

Public Workshop Program

OBESITY CANADA PUBLIC WORKSHOP SATURDAY APRIL 27, 2019 10:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. (light refreshments and lunch included) Governor General Ballroom THE WESTIN OTTAWA, 11 COLONEL BY DRIVE OTTAWA ONTARIO K1N 9H4 SATURDAY, APRIL 27, 2019 9:00am Registration Welcome 10:00am Lisa Schaffer, Chair PEC Stop being a yo-yo 10:15am Arya Sharma, MD/PhD, FRCPC, Scientific Director Obesity Canada Evidence-Based Practices That Will Make You Happier Today 10:45am Gillian Mandich PhD 11:15am Health Break Can food be addictive? 11:30pm Sandra Elia, Certified Food Addiction Councillor Appetite and Weight: What Control Do We Have? 12:00pm Jennifer Brown, RD, MSc. 12:30pm Lunch and Exibitor Viewing Speak Up! Finding hope in seeking the care and understanding you deserve 1:30pm Ian Patton PhD, Director of Advocacy and Public Engagement, Obesity Canada Weight Bias 2:00pm Mary Forhan PhD OT Reg(AB), Ximena Ramos Salas PhD, Angela Alberga PhD, Brenndon Goodman 3:00pm Have your say! Discussing priorities and experiences Closing remarks 3:45pm Lisa Schaffer, Chair PEC Welcome Message Hello and Welcome to Obesity Canada’s Public Workshop — we are thrilled to have you in the room today! Obesity Canada (OC) is dedicated to improving the lives of Canadians affected by obesity and today is the first of what we hope will be many opportunities to connect with Canadian’s just like you. Today’s event is the result of the vision and passion of OC staff and our amazing Public Engagement Committee (PEC). PEC acts as the voice of individuals affected by obesity within OC. -

An Assessment of Fruit and Vegetable Intake, Physical Activity, and Sedentary Behaviour Among Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Students from Northern Ontario

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 10-5-2017 AN ASSESSMENT OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE INTAKE, PHYSICAL ACTIVITY, AND SEDENTARY BEHAVIOUR AMONG INDIGENOUS AND NON-INDIGENOUS STUDENTS FROM NORTHERN ONTARIO Christian O'neil Paton University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Paton, Christian O'neil, "AN ASSESSMENT OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE INTAKE, PHYSICAL ACTIVITY, AND SEDENTARY BEHAVIOUR AMONG INDIGENOUS AND NON-INDIGENOUS STUDENTS FROM NORTHERN ONTARIO" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 7287. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/7287 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. AN ASSESSMENT OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE -

OBESITY TREATMENT for ADULTS in CANADA 2019 Obesitycanada.Ca/Report-Card

REPORT CARD ON ACCESS TO OBESITY TREATMENT FOR ADULTS IN CANADA 2019 obesitycanada.ca/report-card Notice and Disclaimer No part of these materials may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission from Obesity Canada-Obésité Canada. This booklet is provided under the understanding and basis that none of the publisher, the authors or other persons involved in its creation shall be responsible for the accuracy or currency of the contents, or for the results of any action taken on the basis of the information contained in this book or for any errors or omissions contained herein. No reader should act on the basis of any matter contained in this booklet without obtaining appropriate professional advice. The publisher, the authors and other persons involved in this booklet disclaim liability and responsibility resulting from any ideas, products or practices mentioned in the text and disclaim all and any liability and responsibility to any person, regardless of whether such person purchased this booklet, for loss or damage due to errors and omissions in this book and in respect of anything and of the consequence of anything done or omitted to be done by such person in reliance upon the content of the booklet. Parts of this material are based on data and information provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information. However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Canadian Institute for Health Information. -

Improving Obesity Management Training in Family Medicine

Luig et al. BMC Medical Education (2020) 20:5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-019-1908-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Improving obesity management training in family medicine: multi-methods evaluation of the 5AsT-MD pilot course Thea Luig1, Sonja Wicklum2, Melanie Heatherington1, Albert Vu3, Erin Cameron4, Doug Klein5, Arya M. Sharma6,7 and Denise L. Campbell-Scherer1,5,7,8* Abstract Background: Quality, evidence-based obesity management training for family medicine residents is needed to better support patients. To address this gap, we developed a comprehensive course based on the 5As of Obesity Management™ (ASK, ASSESS, ADVISE, AGREE, ASSIST), a framework and suite of resources to improve residents’ knowledge and confidence in obesity counselling. This study assessed the course’s impact on residents’ attitudes, beliefs, and confidence with obesity counselling. Methods: The course combines lectures with a bariatric empathy suit experience, standardized and in-clinic patient practice, and narrative reflections. Using a multi-methods design we measured changes in 42 residents’ attitudes, beliefs, and self-confidence and thematically analyzed the narrative reflections to understand residents’ experience with the course content and pedagogy. Results: Following the course, residents reported improved attitudes towards people living with obesity and improved confidence for obesity counselling. Pre/post improvement in BAOP scores (n = 32) were significant (p < .001)., ATOP scores did not change significantly. Residents showed improvement in assessing root causes of weight gain (p < .01), advising patients on treatment options (p < .05), agreeing with patients on health outcomes (p < .05), assisting patients in addressing their barriers (p < .05), counseling patients on weight gain during pregnancy, (p < .05), counseling patients on depression and anxiety (p < .01), counseling patients on iatrogenic causes of weight gain (p < .01), counseling patients who have children with obesity (p < .05), and referring patients to interdisciplinary providers for care (p < .05). -

It's All in Your Mind

It’s All in Your Mind The brain’s central role in the progression of a chronic disease Dr Sasha High FRCPC Internal Medicine, American Board of Obesity Medicine Diplomate Medical Director, High Metabolic Clinic Faculty/Presenter Disclosure • Faculty/Presenter: Dr. Sarah High • Relationships with commercial interests: I have received honoraria for speaking engagements from Bausch Health, Novo Nordisk, Obesity Canada, and the Canadian Collaborative Research Network. Disclosure of Financial Support This program has received: Financial support from Abbott Diabetes Care, NovoNordisk and Boehringer Ingelheim in the form of an educational grant, and a honorarium from Langs Potential for conflict of interest: Products will be discussed during the presentation. NovoNordisk may benefit from the sale of the following products: - Liraglutide Mitigating Potential Bias Includes evidence based information related to obesity management but is not influenced by the sponsoring organizations Program OBJECTIVES 1. Discover the complex pathophysiology of obesity 2. Understand the mechanisms through which the brain defends the body against weight loss 3. Establish the role of pharmacological intervention in a multi- modal treatment strategy 4. Discuss conversation-starter strategies to create an individualized, sustainable treatment plan What words come to mind when you think OBESITY? Chronic medical condition Complex pathophysiology Neurohormonal control Medical treatments available 6 million Canadians are living with this chronic disease.1 Obesity is a growing problem in Worldwide, 2.8 million Canada. people per year die from overweight/ obesity2. Sources: 1. Canadian Obesity Network. 2018. Understanding Obesity Available at: http://www.obesitycanada.ca/understanding-obesity; 2. WHO. 2017. 10 facts on obesity. Available at: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/obesity/en/# 10 facts on obesity Canadians living with obesity. -

A Qualitative Evaluation of the YMCA's Physical Healthy and Driven Program (PHD)

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMf A Qualitative Evaluation of the YMCA's Physical Healthy and Driven Program (PHD) By Rama Issa Musharbash A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Faculty of Human Kinetics in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Human Kinetics at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2009 ©Rama Musharbash, 2009 Library and Archives Biblioth^que et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'§dition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57634-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57634-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par ('Internet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantias de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Does Impaired Glucose Tolerance Impact Endogenous Carbohydrate

Curriculum Vitae Chu, Lisa NAME IN FULL Lisa Chu CONTACT LMC Healthcare INFORMATION 1929 Bayview Ave Suite 106 Toronto ON M4G 3E8 Phone: 416-645-2928, ext. 9334 Email: [email protected] EDUCATION 2012 – 2017 Ph.D. Medical Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada 2009 – 2011 M.Sc. Kinesiology and Health Science, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 2005 – 2009 B.Sc. in Kinesiology (Honours), Minor in Biochemistry Faculty of Science, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada RESEARCH 2019 – present Clinical Epidemiologist LMC Healthcare, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 2017 – 2019 Postdoctoral Fellowship The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Supervisor: Jill Hamilton, MD, MSc, FRCPC Primary Study: Mechanisms of inflammation, immunity, islet cell and intestinal hormone changes in youth at risk for diabetes (MI4D) 2012 – 2017 Ph.D. Thesis Medical Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada Supervisor: Brian Timmons, PhD Study: Metabolic flexibility in children with obesity: Exercise as a dynamic stimulus to assess metabolic health 2015 Intensive Teaching and Networking, Obesity Summer Boot Camp Obesity Canada, Kananaskis County, Alberta, Canada 2014 Visiting Researcher Loughborough University, Loughborough, United Kingdom Supervisor: Keith Tolfrey, PhD 2009 – 2011 M.Sc. Thesis Kinesiology and Health Science, York University; The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Co-supervisors: Michael Riddell, PhD and Jill Hamilton, MD, MSc, FRCPC 2008 – 2009 Undergraduate Research Thesis -

Aim2be Mhealth Intervention for Children with Overweight and Obesity: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial Louise C

Mâsse et al. Trials (2020) 21:132 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-4080-2 STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access Aim2Be mHealth intervention for children with overweight and obesity: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial Louise C. Mâsse1* , Janae Vlaar1, Janice Macdonald2, Jennifer Bradbury2, Tom Warshawski2, E. Jean Buckler1, Jill Hamilton3, Josephine Ho4, Annick Buchholz5, Katherine M. Morrison6 and Geoff D. C. Ball7 Abstract Background: The prevalence of overweight and obesity remains high in Canada, and the current standard for the treatment of childhood obesity is in-person, family-based, multidisciplinary interventions that target lifestyle behaviors (e.g., diet, physical activity, and sedentary behaviors). These programs are costly to operate, have limited success, and report recruitment and retention challenges. With recent advances in technology, mobile health or mHealth has been presented as a viable alternative to in-person interventions for behavior change, especially with teens. Purpose: The primary aim of this study is to test the efficacy of Aim2Be, a gamified app based on behavior change theory with health coaching to improve weight outcomes (i.e., decrease in standardized body mass index (zBMI)) and lifestyle behaviors (i.e., improve dietary quality, increase fruit and vegetable intake, reduce sugar-sweetened beverage intake, increase physical activity, and reduce screen time) among children 10- to 17-years old with overweight or obesity versus their peers randomized into a waitlist control condition. The secondary aims of this study are to 1) test whether supplementing the Aim2Be program with health coaching increases adherence and 2) examine the mediators and moderators of adherence to the Aim2Be intervention.