Antony Hopkins – a Personal Memoir and Obituary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

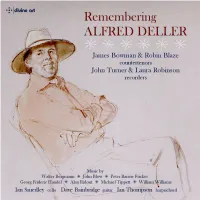

25114Booklet.Pdf

Remembering ALFRED DELLER Walter Bergmann (1902-1988) 1. Pastorale for countertenor & recorder (1946) 3.21 Michael Tippett (1905-1998) Four Inventions for two recorders (1954) 3.40 2. I. Andante 0.55 3. II. Allegro molto 0.34 4. III. Adagio 1.33 5. IV. Allegro moderato 0.36 Alan Ridout (1934-1996) 6. Soliloquy for countertenor, recorder, cello & harpsichord (1985) 5.10 William Williams (d.1701) Sonata in A minor for two recorders & continuo (c.1696) 6.01 7. I. Adagio 1.23 8. II. Vivace 2.58 9. III. Allegro 1.39 John Blow (1649-1708) Ode on the Death of Mr. Henry Purcell, for two countertenors, two recorders & continuo (1696) 32.20 10. I. 4.03 11. II. 4.29 12. III. 3.02 13. IV. 1.51 14. V. 2.32 15. VI. 3.40 16. VII. 2.38 George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Sonata in F major for two recorders & continuo (c.1707) 5.51 17. I. Allegro 2.14 18. II. Grave 1.28 19. III. Allegro 2.09 Peter Racine Fricker (1920-1990) 20. Elegy: The Tomb of St. Eulalia, Op. 25, for countertenor, cello & harpsichord (1955) 7.35 Walter Bergmann (1902-1988) Three Songs for countertenor & guitar (1973, rev. 1983) 4.53 21. No. 1 Mater cantans filio 1.26 22. No. 2 To Musick 2.36 23. No. 3 Chop-Cherry 0.50 Total duration: 59.36 JAMES BOWMAN countertenor (Blow, Fricker, Bergmann songs) ROBIN BLAZE countertenor (Bergmann Pastorale, Ridout, Blow) JOHN TURNER recorder (all works except Fricker & Bergmann Songs) LAURA ROBINSON recorder (Tippett, Williams, Handel) TIM SMEDLEY cello (Ridout, Williams, Blow, Handel, Fricker) DAVE BAINBRIDGE guitar (Bergmann Songs) IAN THOMPSON harpsichord (Ridout, Williams, Blow, Handel, Fricker) MEMORIES OF TIPPETT AND BERGMANN For those of us who grew up in the immediate post-war years, and who were interested in the revival of, and burgeoning enthusiasm for, early music, the names of Tippett and Bergmann are synonymous with those famous Schott editions of music by Purcell and his contemporaries. -

An Actor's Life and Backstage Strife During WWII

Media Release For immediate release June 18, 2021 An actor’s life and backstage strife during WWII INSPIRED by memories of his years working as a dresser for actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit, Ronald Harwood’s evocative, perceptive and hilarious portrait of backstage life comes to Melville Theatre this July. Directed by Jacob Turner, The Dresser is set in England against the backdrop of World War II as a group of Shakespearean actors tour a seaside town and perform in a shabby provincial theatre. The actor-manager, known as “Sir”, struggles to cast his popular Shakespearean productions while the able-bodied men are away fighting. With his troupe beset with problems, he has become exhausted – and it’s up to his devoted dresser Norman, struggling with his own mortality, and stage manager Madge to hold things together. The Dresser scored playwright Ronald Harwood, also responsible for the screenplays Australia, Being Julia and Quartet, best play nominations at the 1982 Tony and Laurence Olivier Awards. He adapted it into a 1983 film, featuring Albert Finney and Tom Courtenay, and received five Academy Award nominations. Another adaptation, featuring Ian McKellen and Anthony Hopkins, made its debut in 2015. “The Dresser follows a performance and the backstage conversations of Sir, the last of the dying breed of English actor-managers, as he struggles through King Lear with the aid of his dresser,” Jacob said. “The action takes place in the main dressing room, wings, stage and backstage corridors of a provincial English theatre during an air raid. “At its heart, the show is a love letter to theatre and the people who sacrifice so much to make it possible.” Jacob believes The Dresser has a multitude of challenges for it to be successful. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

The Capitol Dome

THE CAPITOL DOME The Capitol in the Movies John Quincy Adams and Speakers of the House Irish Artists in the Capitol Complex Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way A MAGAZINE OF HISTORY PUBLISHED BY THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL HISTORICAL SOCIETYVOLUME 55, NUMBER 22018 From the Editor’s Desk Like the lantern shining within the Tholos Dr. Paula Murphy, like Peart, studies atop the Dome whenever either or both America from the British Isles. Her research chambers of Congress are in session, this into Irish and Irish-American contributions issue of The Capitol Dome sheds light in all to the Capitol complex confirms an import- directions. Two of the four articles deal pri- ant artistic legacy while revealing some sur- marily with art, one focuses on politics, and prising contributions from important but one is a fascinating exposé of how the two unsung artists. Her research on this side of can overlap. “the Pond” was supported by a USCHS In the first article, Michael Canning Capitol Fellowship. reveals how the Capitol, far from being only Another Capitol Fellow alumnus, John a palette for other artist’s creations, has been Busch, makes an ingenious case-study of an artist (actor) in its own right. Whether as the historical impact of steam navigation. a walk-on in a cameo role (as in Quiz Show), Throughout the nineteenth century, steam- or a featured performer sharing the marquee boats shared top billing with locomotives as (as in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), the the most celebrated and recognizable motif of Capitol, Library of Congress, and other sites technological progress. -

WTUL Classical Listener's Guide

9 WTUL Classical Lisfener s Guide Don9t F orgef Featured pieces will be aired weekly at 7 a.m., and on Sundays at 7 p.m. and 9 p.m. The week of Jan. 31 -Feb. 5 The week of Feb. 7 - 12 The §ymphony1 Sunday - The 20th Century Sunday with Stefan ext season, the symphony will return. While we despair over its absence, the WTUL Classical Classical Show with Lester o J.S. Bach Cello Suite No.6 in D Major, BWV 1012 Department will do its best to continue their sea Focus on Classic Movie Scores: Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cello N son for them. On the radio, that is. o Virgil Thomson o Franz Waxman The River Lost Command o FJ. Haydn Beginning next month, and for the remainder of the reg Cello Concerto in C, Hob. Vllb No. 1 ular season, WTUL will broadcast the music originally Los Angeles Chamber o Jerome Moross English Chamber Orchestra) Edo DeWaart conducting Orchestra) Neville Mar- The Proud Rebel planned for live performance by the New Orleans Sym riner conducting o Gabriel Faure' phony. More details next issue, but if you have any com Cello Sonata No. 1 in D Minor, Op. 109 ments, please don't hesitate to write or call. Monday with Tom And if you have a chance, please drop by the Encore o Benjamin Britten Monday with Suzanne Shop on 7814 Maple Street. It's a store of previously "Occassional Overture," Op, 38 o Hector Berlioz owned clothing where all sales proceeds go to benefit the Symphonie Fantastique, Op. -

Marie Collier: a Life

Marie Collier: a life Kim Kemmis A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History The University of Sydney 2018 Figure 1. Publicity photo: the housewife diva, 3 July 1965 (Alamy) i Abstract The Australian soprano Marie Collier (1927-1971) is generally remembered for two things: for her performance of the title role in Puccini’s Tosca, especially when she replaced the controversial singer Maria Callas at late notice in 1965; and her tragic death in a fall from a window at the age of forty-four. The focus on Tosca, and the mythology that has grown around the manner of her death, have obscured Collier’s considerable achievements. She sang traditional repertoire with great success in the major opera houses of Europe, North and South America and Australia, and became celebrated for her pioneering performances of twentieth-century works now regularly performed alongside the traditional canon. Collier’s experiences reveal much about post-World War II Australian identity and cultural values, about the ways in which the making of opera changed throughout the world in the 1950s and 1960s, and how women negotiated their changing status and prospects through that period. She exercised her profession in an era when the opera industry became globalised, creating and controlling an image of herself as the ‘housewife-diva’, maintaining her identity as an Australian artist on the international scene, and developing a successful career at the highest level of her artform while creating a fulfilling home life. This study considers the circumstances and mythology of Marie Collier’s death, but more importantly shows her as a woman of the mid-twentieth century navigating the professional and personal spheres to achieve her vision of a life that included art, work and family. -

One-Word Movie Titles

One-Word Movie Titles This challenging crossword is for the true movie buff! We’ve gleaned 30 one- word movie titles from the Internet Movie Database’s list of top 250 movies of all time, as judged by the website’s users. Use the clues to find the name of each movie. Can you find the titles without going to the IMDb? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 EclipseCrossword.com © 2010 word-game-world.com All Rights Reserved. Across 1. 1995, Mel Gibson & James Robinson 5. 1960, Anthony Perkins & Vera Miles 7. 2000, Russell Crowe & Joaquin Phoenix 8. 1996, Ewan McGregor & Ewen Bremner 9. 1996, William H. Macy & Steve Buscemi 14. 1984, F. Murray Abraham & Tom Hulce 15. 1946, Cary Grant & Ingrid Bergman 16. 1972, Laurence Olivier & Michael Caine 18. 1986, Keith David & Forest Whitaker 21. 1979, Tom Skerritt, Sigourney Weaver 22. 1995, Robert De Niro & Sharon Stone 24. 1940, Laurence Olivier & Joan Fontaine 25. 1995, Al Pacino & Robert De Niro 27. 1927, Alfred Abel & Gustav Fröhlich 28. 1975, Roy Scheider & Robert Shaw 29. 2000, Jason Statham & Benicio Del Toro 30. 2000, Guy Pearce & Carrie-Anne Moss Down 2. 2009, Sam Worthington & Zoe Saldana 3. 2007, Patton Oswalt & Iam Holm (voices) 4. 1958, James Stuart & Kim Novak 6. 1974, Jack Nicholson & Faye Dunaway 10. 1982, Ben Kingsley & Candice Bergen 11. 1990, Robert De Niro & Ray Liotta 12. 1986, Sigourney Weaver & Carrie Henn 13. 1942, Humphrey Bogart & Ingrid Bergman 17. -

FILMS and THEIR STARS 1. CK: OW Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 2

FILMS AND THEIR STARS 1. CK: OW Citizen Kane: Orson Welles 2. TGTBATU: CE The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: Clint Eastwood 3. RFTS: KM Reach for the Sky: Kenneth More 4. FG; TH Forest Gump: Tom Hanks 5. TGE: SM/CB The Great Escape: Steve McQueen and Charles Bronson ( OK. I got it wrong!) 6. TS: PN/RR The Sting: Paul Newman and Robert Redford 7. GWTW: VL Gone with the Wind: Vivien Leigh 8. MOTOE: PU Murder on the Orient Express; Peter Ustinov (but it wasn’t it was Albert Finney! DOTN would be correct) 9. D: TH/HS/KB Dunkirk: Tom Hardy, Harry Styles, Kenneth Branagh 10. HN: GC High Noon: Gary Cooper 11. TS: JN The Shining: Jack Nicholson 12. G: BK Gandhi: Ben Kingsley 13. A: NK/HJ Australia: Nicole Kidman, Hugh Jackman 14. OGP: HF On Golden Pond: Henry Fonda 15. TDD: LM/CB/TS The Dirty Dozen: Lee Marvin, Charles Bronson, Telly Savalas 16. A: MC Alfie: Michael Caine 17. TDH: RDN The Deer Hunter: Robert De Niro 18. GWCTD: ST/SP Guess who’s coming to Dinner: Spencer Tracy, Sidney Poitier 19. TKS: CF The King’s Speech: Colin Firth 20. LOA: POT/OS Lawrence of Arabia: Peter O’Toole, Omar Shariff 21. C: ET/RB Cleopatra: Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton 22. MC: JV/DH Midnight Cowboy: Jon Voight, Dustin Hoffman 23. P: AP/JL Psycho: Anthony Perkins, Janet Leigh 24. TG: JW True Grit: John Wayne 25. TEHL: DS The Eagle has landed: Donald Sutherland. 26. SLIH: MM Some like it Hot: Marilyn Monroe 27. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Laurence Olivier in Hamlet (1949)

1 Laurence Olivier in Hamlet (1949) In the late 1930s and early 1940s, when Samuel Goldwyn, MGM, and David Selznick were wooing him, Laurence Olivier chose not to become a movie star “like dear Cary.” After playing Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights (1939), Darcy in Pride and Prejudice (1940), and Maxim Dewinter in Rebecca (1940), he appeared in Hollywood pictures sparingly and tried to avoid a fixed persona. He nevertheless became the symbol of what midcentury America thought of as a distinguished actor, and was the most successful English theatrical type in the movies. He wasn’t romantically flamboyant (Orson Welles was closer to that), he wasn’t a naturalist like the students of the Method, he wasn’t a Brechtian, and he wasn’t the sort of movie actor who plays variations on a single character. He belonged instead to a school of disciplined, tastefully romantic verisimilitude, and within that school was a master. He was also the best-known Shakespearian in films. Olivier often said that his favorite movie role was the working-class comedian Archie Rice in The Entertainer (1960), but his performances in the Shakespeare films that he directed are more representative of his skills and more significant in film history. Based on canonical texts with a long performance history, they foreground his stylistic choices 2 and make his influences relatively easy to identify. His version of Hamlet (1949), for example, seems to derive pretty equally from the English romantics, Sigmund Freud, and William Wyler. These sources are not so eclectic as they might appear. Romantic-realist ideas of narrative shaped nearly all feature films of the period; Wyler had been the director of Wuthering Heights and at one point was scheduled to direct Olivier’s production of Henry V; and Olivier’s conceptions of character and performance are similar to the ones that shaped Hollywood in the 1940s, when Freud was in vogue. -

Anthony Hopkins

Anthony Hopkins From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Anthony hopkins) For the composer, see Antony Hopkins. Sir Anthony Hopkins Hopkins at the Tuscan Sun Festival, Cortona, 2009 Born Philip Anthony Hopkins 31 December 1937 (age 73) Port Talbot, Glamorgan, Wales Occupation Actor Years active 1967±present Petronella Barker (1967±72; divorced) Spouse Jennifer Lynton (1973±2002; divorced) Stella Arroyave (2003±present) Sir Philip Anthony Hopkins, CBE (born 31 December 1937), best known as Anthony Hopkins, is a Welsh actor of film, stage and television. Considered to be one of the greatest living actors,[1][2][3] Hopkins is perhaps best known for his portrayal of cannibalistic serial killerHannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs (for which he received the Academy Award for Best Actor), its sequel Hannibal, and its prequel Red Dragon. Other prominent film credits includeThe Lion in Winter, Magic, The Elephant Man, 84 Charing Cross Road, Dracula, Legends of the Fall, The Remains of the Day, Amistad, Nixon, and Fracture. Hopkins was born and brought up in Wales. Retaining his British citizenship, he became a U.S. citizen on 12 April 2000.[4]Hopkins' films have spanned a wide variety of genres, from family films to horror. As well as his Academy Award, Hopkins has also won three BAFTA Awards, two Emmys, a Golden Globe and a Cecil B. DeMille Award. Hopkins was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 1993 for services to the arts.[5] He received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2003, and was made a Fellow of the British Academy of Film and Television Arts in 2008.[6][7] Contents [hide] 1 Early life 2 Career o 2.1 Roles o 2.2 Acting style o 2.3 Hannibal Lecter 3 Personal life 4 Other work 5 Awards 6 Filmography 7 References 8 External links [edit]Early life Hopkins was born in Margam, Port Talbot, Wales, the son of Muriel Anne (née Yeats) and Richard Arthur Hopkins, a baker.[8] His schooldays were unproductive; he found that he would rather immerse himself in art, such as painting and drawing, or playing the piano, than attend to his studies.