Overhauling U.S. Security Sector Assistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aussie Classics Hits - 180 Songs

Available from Karaoke Home Entertainment Australia and New Zealand Aussie Classics Hits - 180 Songs 1 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc 2 Absolutely Everybody Vanessa Amorosi 3 Age Of Reason John Farnham 4 All I Do Daryl Braithwaite 5 All My Friends Are Getting Married Skyhooks 6 Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again The Angels 7 Amazing Alex Lloyd 8 Amazing Vanessa Amorosi 9 Animal Song Savage Garden 10 April Sun In Cuba Dragon 11 Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet 12 Art Of Love Guy Sebastian, Jordin Sparks 13 Aussie Rules I Thank You For The Best Kevin Johnson Years Of Our Lives 14 Australian Boy Lee Kernaghan 15 Barbados The Models 16 Battle Scars Guy Sebastian, Lupe Fiasco 17 Bedroom Eyes Kate Ceberano 18 Before The Devil Knows You're Dead Jimmy Barnes 19 Before Too Long Paul Kelly, The Coloured Girls 20 Better Be Home Soon Crowded House 21 Better Than John Butler Trio 22 Big Mistake Natalie Imbruglia 23 Black Betty Spiderbait 24 Bluebird Kasey Chambers 25 Bopping The Blues Blackfeather 26 Born A Woman Judy Stone 27 Born To Try Delta Goodrem 28 Bow River Cold Chisel 29 Boys Will Be Boys Choir Boys 30 Breakfast At Sweethearts Cold Chisel 31 Burn For You John Farnham 32 Buses And Trains Bachelor Girl 33 Chained To The Wheel Black Sorrows 34 Cheap Wine Cold Chisel 35 Come On Aussie Come On Shannon Noll 36 Come Said The Boy Mondo Rock 37 Compulsory Hero 1927 38 Cool World Mondo Rock 39 Crazy Icehouse 40 Cry In Shame Johnny Diesel, The Injectors 41 Dancing With A Broken Heart Delta Goodrem 42 Devil Inside Inxs 43 Do It With Madonna The Androids 44 -

A Conversation with Raghida Dergham

TM: Welcome everybody to this sixth installment in the Harvard Kennedy School American University in Cairo series of conversations with Arab thought leaders on the 2020 U.S. election and America's changing role in the Middle East. I’m going to turn this over to my co-pilot Karim Haggag to introduce our distinguished guest for today but let me Just remind everybody what it is we are doing here. Each weeK we've been meeting with leading Arabs from the worlds of policy practice and ideas to explore their perceptions of the current season of politics in the United States and to get their sense of where they thinK the United States, the world's sole superpower, is heading, and particularly, what all of this means for the Middle East. So far in this series, we've interviewed some really interesting and extraordinary people, including prime minister Ayad Allawi, the Emirati intellectual AbdulKhaleq Abdulla, the Iraqi-Emirati Journalist Mina al-Oraibi, and these conversations will soon be available on our website and on podcast streaming services. We also have one more conversation. This is the penultimate conversation before we break for the winter, one more conversation next weeK with the Saudi editor of the al-Arabiya English, Mohammed Alyahya, and we hope that you'll Join us for that. Let me now turn it over to my co-pilot in this endeavor, Karim Haggag of the American University in Cairo School of Global affairs and Public Policy. Karim. KH: ThanK you, TareK, and thanK you everyone for Joining us for this afternoon's discussion. -

Past Concerts and Events

Rochford Wines - past concerts and events 2021 23 January Sounds Better Together 20 March Wine Machine #1 21 March Wine Machine #2 17 April The Big 90s Party 18 April Vine Warp 24 April Grapevine Presents 2020 18 April The Big 90s Party 28 March Wine Machine 22 February A-ha & Rick Astley 1 February Elton John 31 January Elton John 10 January Cold Chisel 2019 9 November Rob Thomas 13 April The Big 80s Party 6 April Hot Dub Wine Machine 23 February ADOTG – Bryan Ferry 2018 9 December ADOTG – John Farnham 8 December ADOTG – John Farnham 24 November Grapevine Gathering 24 March Hot Dub Wine Machine 22 February AEOTG – Robbie Williams 10 February RNB Vine Days 2017 17 December Rochford Wines Family Christmas Day 16 December ADOTG – Human Nature 10 December ADOTG – KC & The Sunshine Band 26 November Wine Quest's Cuban Festival 2017 25 November Grapevine Gathering 18 November ADOTG – Stevie Nicks & The Pretenders 29 October Gertrude Opera presents Mozart’s The Magic Flute 27 October Gertrude Opera presents Mozart’s The Magic Flute 10 October Wedfest @ Rochford Wines 1 October ADOTG – Sir Elton John 16 June Rochford Wines presents Anthony Gerace 29 April Rochford Wines presents The Decibelles Up Close 8 April Cyndi Lauper & Blondie 2 April 2017 Yarra Valley Wine & Food Festival 1 April 2017 Yarra Valley Wine & Food Festival 1 April Twilight Concert - Bjorn Again 25 March Hot Dub Wine Machine 4 February ADOTG - Simple Minds & B52s 2016 18 December Rochford Wines Family Christmas Day 26 November ADOTG Garbage & The Temper Trap 13 November ADOTG -

Russia and Saudi Arabia: Old Disenchantments, New Challenges by John W

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 35 Russia and Saudi Arabia: Old Disenchantments, New Challenges by John W. Parker and Thomas F. Lynch III Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Vladimir Putin presented an artifact made of mammoth tusk to Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman Al Saud in Riyadh, October 14–15, 2019 (President of Russia Web site) Russia and Saudi Arabia Russia and Saudia Arabia: Old Disenchantments, New Challenges By John W. Parker and Thomas F. Lynch III Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 35 Series Editor: Denise Natali National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2021 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Imperatives of Transformation: Changing Character of Conflict in the Emerging World Order

Imperatives of Transformation: Changing Character of Conflict in the Emerging World Order V K Ahluwalia The character of war in the 21st century has changed, and if we fail to keep pace with the speed of war, we will lose the ability to compete. — General Joe Dunford, 19th Chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, 20171 Introduction It is extremely difficult to crystal-gaze and predict the future with certainty. In hindsight, one can say that the rapid changes in the geo-political, economic, social, cultural and technological domains have had a profound impact on the emerging geo-strategic environment. With a plethora of disruptive technologies, the unknown effects of emerging technologies, asymmetric threats and the revolution in autonomous systems and communications, the global environment has been in a state of continuous change and flux. Resultantly, the envisaged threats and challenges to national security, both traditional and non-traditional, have also undergone significant change. The complexities of which need to be analysed in order to formulate the future course of action. Factors such as external security threats, religious and ethnic extremism, population growth and unemployment, societal tensions, severe competition for natural resources, climate change and environmental degradation are likely to ensure that Lieutenant General (Dr) VK Ahluwalia (Retd) is the Director of the Centre for Land Warfare Studies. CLAWS Journal l Summer 2019 21 V K AHLUWALIA armed conflicts will persist, perhaps with greater intensity. To say so, in a large number of cases, trans-national neighbouring forces and non-state actors have been indulging in abetting insurgencies, terrorism, violence and organised crime, thus, perpetuating instability and conflicts. -

Congressional Enforcement of International Human Rights

St. John's University School of Law St. John's Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications 2020 Congressional Enforcement of International Human Rights Margaret E. McGuiness Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/faculty_publications Part of the International Law Commons ARTICLE CONGRESSIONAL ENFORCEMENT OF INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS Margaret E. McGuinness* I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 9 II. HUMAN RIGHTS MANDATES AS ALTERNATIVES TO HUMAN RIGHTS TREATIES ................................................... 15 III. CONGRESSIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS MANDATES IN THE COURTS .......................................................................................... 29 IV. CONCLUSION ..................................................................................... 36 I. INTRODUCTION On October 2, 2018, Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi journalist based in the United States, walked into the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, Turkey, where he was brutally murdered and dismembered by Saudi government agents.1 It was a brazen violation of the most fundamental, internationally recognized human rights, carried out by one close US ally in the territory of another close ally.2 The US intelligence community quickly determined that the Saudi government and its Crown Prince, Mohammed Bin Salman, were responsible for the killing.3 Members of Congress briefed by the * Professor of Law, Co-Director, Center for International and Comparative Law, St. John's University School of Law. Thank you to Samantha Ragonesi, Michael Campbell, Kelsey Halloran, the editors of the Fordham International Law Journal, and the participants of the February 2020 Symposium on the Global Judiciary. 1. Agnes Callamard, Khashoggi Killing: UN Human Rights Expert Says Saudi Arabia is Responsible for “Premeditated Execution”, OHCHR, https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=24713 [https://perma.cc/LVT8-FFHC] (last visited Oct. 21, 2019). 2. Id. -

Khashoggi's Death and Its Repercussions on the Saudi Position with Turkey

ORSAM Analysis No: 224 / January 2019 KHASHOGGI’S DEATH AND ITS REPERCUSSIONS ON THE SAUDI POSITION WITH TURKEY IHAB OMAR ORSAM Copyright Ankara - TURKEY ORSAM © 2019 Content of this publication is copyrighted to ORSAM. Except reasonable and partial quotation and use under the Act No. 5846, Law on Intellectual and Artistic Works, via proper citation, the content may not be used or re-published without prior permission by ORSAM. The views ex- pressed in this publication reflect only the opinions of its authors and do not represent the institu- tional opinion of ORSAM. ISBN:978-605-80419-3-6 Center for Middle Eastern Studies Adress : Mustafa Kemal Mah. 2128 Sk. No: 3 Çankaya, ANKARA Phone: +90 (312) 430 26 09 Faks: +90 (312) 430 39 48 Email: [email protected] Photos: Associated Press Analiz No:224 ORSAM ANALYSIS KHASHOGGI 'S DEATH AND ITS REPERCUSSIONS ON THE SAUDI POSITION WITH TURKEY About the Author Ihab Omar Ihab Omar is an Egyptian journalist and researcher specializing in Arab affairs. He holds a Bachelor of Media degree and General Diploma in Education. He covered the Arab events of many Arab newspapers and international sites. He covered closely the events of the Arab Spring in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen. January 2019 orsam.org.tr 2 Khashoggi's Death and its Repercussions on the Saudi Position With Turkey Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................3 Who was Jamal Khashoggi? ..........................................................................................................3 -

Informe De La Comisión Hacia El Cierre De Guantánamo

OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 20/15 3 Junio 2015 Original: Inglés COMISIÓN INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS Hacia el cierre de Guantánamo 2015 www.cidh.org OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Hacia el cierre de Guantánamo / Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. v. ; cm. (OAS. Documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L) ISBN 978-0-8270-6422-5 1. Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp. 2. Prisoners of war--Legal status, laws, etc.--Cuba--Guantánamo Bay Naval Base. 3. Prisoners of war--United States. 4. Detention of persons--Cuba-- Guantánamo Bay Naval Base. I. Title. II. OAS. Documentos oficiales ; OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.20/15 COMISIÓN INTERAMERICANA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS Miembros Rose-Marie Belle Antoine James L. Cavallaro* José de Jesús Orozco Henríquez Felipe González Tracy Robinson Rosa María Ortiz Paulo Vannuchi Secretario Ejecutivo Emilio Álvarez-Icaza Longoria Secretaria Ejecutiva Adjunta Elizabeth Abi-Mershed * Conforme a lo dispuesto en el artículo 17.2 del Reglamento de la Comisión, el Comisionado James L. Cavallaro, de nacionalidad estadounidense, no participó en el debate ni en la decisión del presente Informe. Aprobado por la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos el 3 de junio de 2015 ÍNDICE RESUMEN EJECUTIVO 9 CAPÍTULO 1 | INTRODUCCIÓN 15 A. Antecedentes 15 B. Metodología 16 C. Estructura del informe 17 D. Preparación y aprobación del informe 19 CAPÍTULO 2 | EVOLUCIÓN DE LAS INICIATIVAS DE LA CIDH RELATIVAS A GUANTÁNAMO 23 A. El mandato de la CIDH 23 B. Medidas cautelares 25 C. Resoluciones 29 D. Audiencias públicas 31 E. Sistema de peticiones individuales 32 F. -

COUNTER RELEASE 5: an Independent Review

COUNTER RELEASE 5: an independent review Dave Jago, Mark Sandler, and Alicia Wise Contacts: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................................... 3 What We Learned ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Query logs and FAQs ................................................................................................................................... 4 Audit reports ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Survey responses: libraries and consortia .................................................................................................. 6 Survey responses: publishers ....................................................................................................................10 Librarian Focus Groups .............................................................................................................................16 Uses of COUNTER information..............................................................................................................16 Things that can be done with COUNTER 5 that were not possible before ...........................................17 The transition from R4 to R5.................................................................................................................18 -

Human Rights on Capitol Hill

Amnesty International USA November edition HUMAN RIGHTS ON CAPITOL HILL November 13, 2018 In this edition: 1) President Trump’s Proclamation Violates the Rights of Asylum Seekers 2) Saudi Arabia - Amnesty International USA Protests Murder of Jamal Khashoggi and U.S. Arms Sales to Saudi Arabia 3) India - Indian Government Raids Amnesty India Office in Attempt to Halt Human Rights Work 4) Hungary - State Department Should Reinstate Program to Promote Independent Media 5) Amnesty International USA Urges Congress to Adopt Human Rights Defenders’ Cases 6) Myanmar - Amnesty International Withdraws the Ambassador of Conscience Award from Aung San Suu Kyi 1) President Trump’s Proclamation Violates the Rights of Asylum Seekers In November 2018 President Trump issued a proclamation, along with a joint interim DOJ and DHS rule, that seeks to radically restrict the rights of asylum seekers arriving from the southern border. For the first time the U.S. government is inventing a new rule that requires asylum seekers to pres- ent themselves at official ports of entry. This new rule violates asylum seekers’ rights under U.S. and international law to seek asylum whether or not they are at an official port of entry. In October 2018 Amnesty International researchers traveled with the Honduran caravan as it migrated towards Northern Mexico. Mexican shelters are overflowing with thousands of families in children without proper food, medical care or protection. While some have chosen to seek asylum in Mexico, Mexico cannot be con- sidered a uniformly safe country for all asylum seekers. In addition to the Trump administration’s new rule, DHS moves to detain families indefinitely. -

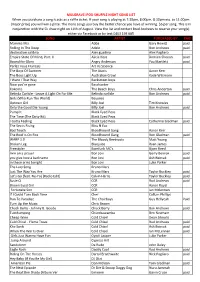

MULGRAVE IPOD SHUFFLE NIGHT SONG LIST When You Purchase a Song It Acts As a Raffle Ticket

MULGRAVE IPOD SHUFFLE NIGHT SONG LIST When you purchase a song it acts as a raffle ticket. If your song is playing at 7:30pm, 8:00pm, 8:30pm etc. to 11:00pm (major prize) you will win a prize. The more songs you buy the better chance you have of winning. $5 per song. This is in conjunction with the 5k draw night on 11th of August. View the list and contact Brad Andrews to reserve your song(s) either via Facebook or by text 0403 193 085 SONG ARTIST PURCHASED BY PAID Mamma Mia Abba Gary Hewitt paid Rolling In The Deep Adele Bon Andrews paid destination calibria Alex guadino Alex Pagliaro Empire State Of Mind, Part. II Alicia Keys Damien Sheean paid Bound for Glory Angry Anderson Paul Bartlett paid Parlez Vous Francais Art Vs Science The Boys Of Summer The Ataris Aaron Kerr The Boys Light Up Australian Crawl Kade Wilsmore I Want I That Way Backstreet boys Now you're gone Basshunter Kokomo The Beach Boys Chris Anderton paid Belinda Carlisle ‐ Leave A Light On For Me Belinda carlisle Bon Andrews paid Girls (Who Run The World) Beyonce Uptown Girl Billy Joel Tim Knowles Only the Good Die Young Billy Joel Bon Andrews paid Pump It Black Eyed Peas The Time (The Dirty Bit) Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Catherine Gladman paid The Sea is Rising Bliss N Eso Bad Touch Bloodhound Gang Aaron Kerr The Roof Is On Fire Bloodhound Gang Ron Gladman paid WARP 1.9 The Bloody Beetroots Matt Young Broken Leg Bluejuice Ryan James Freestyler Bomfunk MC's Bjorn Reed livin on a prayer Bon Jovi Gerry Beiniak paid you give love a bad name Bon Jovi Ash Beiniak paid in these arms tonight Bon Jovi Luke Parker The Lazy Song Bruno Mars Just The Way You Are Bruno Mars Taylor Buckley paid Let's Go (feat. -

Corporate and Foreign Interests Behind White House Push to Transfer U.S

Corporate and Foreign Interests Behind White House Push to Transfer U.S. Nuclear Technology to Saudi Arabia Prepared for Chairman Elijah E. Cummings Second Interim Staff Report Committee on Oversight and Reform U.S. House of Representatives July 2019 oversight.house.gov EXECUTIVE SUMMARY On February 19, 2019, the Committee on Oversight and Reform issued an interim staff report prepared for Chairman Elijah E. Cummings after multiple whistleblowers came forward to warn about efforts inside the White House to rush the transfer of U.S. nuclear technology to Saudi Arabia. As explained in the first interim staff report, under Section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act, the United States may not transfer nuclear technology to a foreign country without the approval of Congress in order to ensure that the agreement meets nine nonproliferation requirements to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. These agreements, commonly known as “123 Agreements,” are typically negotiated with career experts at the National Security Council (NSC) and the Departments of State, Defense, and Energy. The “Gold Standard” for 123 Agreements is a commitment by the foreign country not to enrich or re-process nuclear fuel and not to engage in activities linked to the risk of nuclear proliferation. During the Obama Administration, Saudi Arabia refused to agree to the Gold Standard. During the Trump Administration, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) went further, proclaiming: “Without a doubt, if Iran developed a nuclear bomb, we will follow suit as soon as possible.” There is strong bipartisan opposition to abandoning the “Gold Standard” for Saudi Arabia in any future 123 Agreement.