Sceloporus Jarrovii) L.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Kansas Biological Survey Report #151 Kelly Kindscher, Randy Jennings, William Norris, and Roland Shook September 8, 2008 Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Cover Photo: The Gila River in New Mexico. Photo by Kelly Kindscher, September 2006. Kelly Kindscher, Associate Scientist, Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, 2101 Constant Avenue, Lawrence, KS 66047, Email: [email protected] Randy Jennings, Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] William Norris, Associate Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Roland Shook, Emeritus Professor, Biology, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Citation: Kindscher, K., R. Jennings, W. Norris, and R. Shook. Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico. Open-File Report No. 151. Kansas Biological Survey, Lawrence, KS. ii + 42 pp. Abstract During 2006 and 2007 our research crews collected data on plants, vegetation, birds, reptiles, and amphibians at 49 sites along the Gila River in southwest New Mexico from upstream of the Gila Cliff Dwellings on the Middle and West Forks of the Gila to sites below the town of Red Rock, New Mexico. -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus Poinsettii

856.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus poinsettii Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Webb, R.G. 2008. Sceloporus poinsettii. Sceloporus poinsettii Baird and Girard Crevice Spiny Lizard Sceloporus poinsettii Baird and Girard 1852:126. Type-locality, “Rio San Pedro of the Rio Grande del Norte, and the province of Sonora,” restricted to either the southern part of the Big Burro Moun- tains or the vicinity of Santa Rita, Grant County, New Mexico by Webb (1988). Lectotype, National Figure 1. Adult male Sceloporus poinsettii poinsettii (UTEP Museum of Natural History (USNM) 2952 (subse- 8714) from the Magdalena Mountains, Socorro County, quently recataloged as USNM 292580), adult New Mexico (photo by author). male, collected by John H. Clark in company with Col. James D. Graham during his tenure with the U.S.-Mexican Boundary Commission in late Au- gust 1851 (examined by author). See Remarks. Sceloporus poinsetii: Duméril 1858:547. Lapsus. Tropidolepis poinsetti: Dugès 1869:143. Invalid emendation (see Remarks). Sceloporus torquatus Var. C.: Bocourt 1874:173. Sceloporus poinsetti: Yarrow “1882"[1883]:58. Invalid emendation. S.[celoporus] t.[orquatus] poinsettii: Cope 1885:402. Seloporus poinsettiii: Herrick, Terry, and Herrick 1899:123. Lapsus. Sceloporus torquatus poinsetti: Brown 1903:546. Sceloporus poissetti: Král 1969:187. Lapsus. Figure 2. Adult female Sceloporus poinsettii axtelli (UTEP S.[celoporus] poinssetti: Méndez-De la Cruz and Gu- 11510) from Alamo Mountain (Cornudas Mountains), tiérrez-Mayén 1991:2. Lapsus. Otero County, New Mexico (photo by author). Scelophorus poinsettii: Cloud, Mallouf, Mercado-Al- linger, Hoyt, Kenmotsu, Sanchez, and Madrid 1994:119. Lapsus. Sceloporus poinsetti aureolus: Auth, Smith, Brown, and Lintz 2000:72. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Sceloporus Jarrovii)By Chiggers and Malaria in the Chiricahua Mountains, Arizona

THE SOUTHWESTERN NATURALIST 54(2):204–207 JUNE 2009 NOTE INFECTION OF YARROW’S SPINY LIZARDS (SCELOPORUS JARROVII)BY CHIGGERS AND MALARIA IN THE CHIRICAHUA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA GRE´ GORY BULTE´ ,* ALANA C. PLUMMER,ANNE THIBAUDEAU, AND GABRIEL BLOUIN-DEMERS Department of Biology, University of Ottawa, 30 Marie-Curie, Ottawa, ON K1N 6N5, Canada *Correspondent: [email protected] ABSTRACT—We measured prevalence of malaria infection and prevalence and intensity of chigger infection in Yarrow’s spiny lizards (Sceloporus jarrovii) from three sites in the Chiricahua Mountains of southeastern Arizona. Our primary objective was to compare parasite load among sites, sexes, and reproductive classes. We also compared our findings to those of previous studies on malaria and chiggers in S. jarrovii from the same area. Of lizards examined, 85 and 93% were infected by malaria and chiggers, respectively. Prevalence of malaria was two times higher than previously reported for the same area, while prevalence of chiggers was similar to previous findings. Intensity of chigger infection was variable among sites, but not among reproductive classes. The site with the highest intensity of chigger infection also had the most vegetative cover, suggesting that this habitat was more favorable for non- parasitic adult chiggers. RESUMEN—Medimos la frecuencia de infeccio´n por malaria y la frecuencia e intensidad de infeccio´n por a´caros en la lagartija espinosa Sceloporus jarrovii de tres sitios en las montan˜as Chiricahua del sureste de Arizona. Nuestro objetivo principal fue comparar la carga de para´sitos entre sitios, sexos y clases reproductivas. Adicionalmente comparamos nuestros hallazgos con estudios previos sobre malaria y a´caros para esta especie en la misma a´rea. -

Sprint Performance of Phrynosomatid Lizards, Measured on a High-Speed Treadmill, Correlates with Hindlimb Length

J. Zool., Lond. (1999) 248, 255±265 # 1999 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom Sprint performance of phrynosomatid lizards, measured on a high-speed treadmill, correlates with hindlimb length Kevin E. Bonine and Theodore Garland, Jr Department of Zoology, University of Wisconsin, 430 Lincoln Drive, Madison, WI 53706-1381, U.S.A. (Accepted 19 September 1998) Abstract We measured sprint performance of phrynosomatid lizards and selected outgroups (n = 27 species). Maximal sprint running speeds were obtained with a new measurement technique, a high-speed treadmill (H.S.T.). Animals were measured at their approximate ®eld-active body temperatures once on both of 2 consecutive days. Within species, individual variation in speed measurements was consistent between trial days and repeatabilities were similar to values reported previously for photocell-timed racetrack measure- ments. Multiple regression with phylogenetically independent contrasts indicates that interspeci®c variation in maximal speed is positively correlated with hindlimb span, but not signi®cantly related to either body mass or body temperature. Among the three phrynosomatid subclades, sand lizards (Uma, Callisaurus, Cophosaurus, Holbrookia) have the highest sprint speeds and longest hindlimbs, horned lizards (Phryno- soma) exhibit the lowest speeds and shortest limbs, and the Sceloporus group (including Uta and Urosaurus) is intermediate in both speed and hindlimb span. Key words: comparative method, lizard, locomotion, morphometrics, phrynosomatidae, sprint speed INTRODUCTION Fig. 1; Montanucci, 1987; de Queiroz, 1992; Wiens & Reeder, 1997) that exhibit large variation in locomotor Evolutionary physiologists and functional morpholo- morphology and performance, behaviour, and ecology gists emphasize the importance of direct measurements (Stebbins, 1985; Conant & Collins, 1991; Garland, 1994; of whole-animal performance (Arnold, 1983; Garland & Miles, 1994a). -

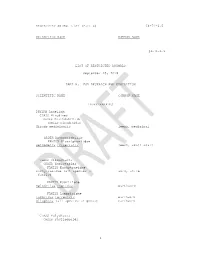

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME §4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS September 25, 2018 PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes -

Amphibians and Reptiles of the State of Coahuila, Mexico, with Comparison with Adjoining States

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 593: 117–137Amphibians (2016) and reptiles of the state of Coahuila, Mexico, with comparison... 117 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.593.8484 CHECKLIST http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Amphibians and reptiles of the state of Coahuila, Mexico, with comparison with adjoining states Julio A. Lemos-Espinal1, Geoffrey R. Smith2 1 Laboratorio de Ecología-UBIPRO, FES Iztacala UNAM. Avenida los Barrios 1, Los Reyes Iztacala, Tlalnepantla, edo. de México, Mexico – 54090 2 Department of Biology, Denison University, Granville, OH, USA 43023 Corresponding author: Julio A. Lemos-Espinal ([email protected]) Academic editor: A. Herrel | Received 15 March 2016 | Accepted 25 April 2016 | Published 26 May 2016 http://zoobank.org/F70B9F37-0742-486F-9B87-F9E64F993E1E Citation: Lemos-Espinal JA, Smith GR (2016) Amphibians and reptiles of the state of Coahuila, Mexico, with comparison with adjoining statese. ZooKeys 593: 117–137. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.593.8484 Abstract We compiled a checklist of the amphibians and reptiles of the state of Coahuila, Mexico. The list com- prises 133 species (24 amphibians, 109 reptiles), representing 27 families (9 amphibians, 18 reptiles) and 65 genera (16 amphibians, 49 reptiles). Coahuila has a high richness of lizards in the genus Sceloporus. Coahuila has relatively few state endemics, but has several regional endemics. Overlap in the herpetofauna of Coahuila and bordering states is fairly extensive. Of the 132 species of native amphibians and reptiles, eight are listed as Vulnerable, six as Near Threatened, and six as Endangered in the IUCN Red List. In the SEMARNAT listing, 19 species are Subject to Special Protection, 26 are Threatened, and three are in Danger of Extinction. -

Prevalence of Ectoparasite Infestation in Neonate Yarrow's Spiny Lizards, Sceloporus Jarrovii (Phrynosomatidae), from Arizona

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 54 Number 2 Article 13 4-29-1994 Prevalence of ectoparasite infestation in neonate Yarrow's spiny lizards, Sceloporus jarrovii (Phrynosomatidae), from Arizona Stephen R. Goldberg Whittier College, Whittier, California Charles R. Bursey Pennsylvania State University, Shenago Valley Campus, Sharon, Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Goldberg, Stephen R. and Bursey, Charles R. (1994) "Prevalence of ectoparasite infestation in neonate Yarrow's spiny lizards, Sceloporus jarrovii (Phrynosomatidae), from Arizona," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 54 : No. 2 , Article 13. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol54/iss2/13 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Basin Naturalist 54(2), ©1994, pp. 189-190 PREVALENCE OF ECTOPARASITE INFESTATION IN NEONATE YARROW'S SPINY LIZARDS, SCELOPORUS JARROVII (PHRYNOSOMATIDAE), FROM ARIZONA Stephen R. Goldbergl and Charles R. Bursey2 Key words: chigger, Eutrombicula lipovskyana, mite, Geckobiella texana, Sceloporus jarrovii, Phrynosomatidae, neonate, prevaleruJe, intensity. While it is well known that ectoparasites Specimens were deposited in the herpetology infest lizards (Frank 1981), we know of no collection of the Los Angeles County Natural reports concerning how quickly newborn History Museum (LACM) (139070-139105). (neonate) lizards are infested under natural conditions. Ectoparasites have been shown to RESULTS AND DISCUSSION cause a diffuse inflammatory response in the skin of infected lizards from natural popula Lizards in the 1991 sample averaged 30.1 tions (Goldberg and Bursey 1991, Goldberg + 2.0 mm SVL, range 26-36 mm. -

Gastrointestinal Helminths of the Crevice Spiny Lizard, Sceloporus Poinsettii (Phrynosomatidae)

OF WASHINGTON, VOLUME 60, NUMBER 2, JULY 1993 263 Chandler, A. C., and R. Rausch. 1947. A study of book of North American Birds. Vol. 4. Yale Uni- strigeids from owls in north central United States. versity Press, New Haven, Connecticut. Transactions of the American Microscopical So- Newsom, I. E., and E. N. Stout. 1933. Proventriculitis ciety 66:283-292. in chickens due to flukes. Veterinary Medicine 28: Dubois, G., and R. Rausch. 1948. Seconde contri- 462^63. bution a 1'etude des-strigeides—(Trematode) Nord- Pence, D. B., J. M. Aho, A. O. Bush, A. G. Canaris, Americains. Societe Neuchateloise des Sciences J. A. Conti, W. R. Davidson, T. A. Dick, G. W. Natureles 71:29-61. Esch, T. Goater, W. Fitzpatrick, D. J. Forrester, , and . 1950a. A contribution to the J. C. Holmes, W. M. Samuel, J. M. Kinsella, J. study of North American strigeoids (Trematoda). Moore, R. L. Rausch, W. Threfall, and T. A. American Midland Naturalist 43:1-31. Wheeler. 1988. In Letters to the editor. Journal , and . 1950b. Troisieme contribution of Parasitology 74:197-198. al'etude des strigeides. (Trematode) Nord-Amer- Ramalingam, S., and W. M. Samuel. 1978. Hel- icains. Societe Neuchateloise des Sciences Natu- minths in the great horned owl. Bubo virginianus, reles 73:19-50. and snowy owl, Nyctea scandiaca, of Alberta. Ca- Morgan, B. B. 1943. The Physalopterinae (Nema- nadian Journal of Zoology 56:2454-2456. toda) of Aves. Transactions of the American Mi- Rausch, R. 1948. Observations on cestodes in North croscopical Society 62:72-80. American owls with the description of Choano- . -

The Karyotype of Sceloporus Macdougallii (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae)

Rev. Esp. Herp. (2004) 18:75-78 The karyotype of Sceloporus macdougallii (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae) FERNANDO MENDOZA-QUIJANO 1 & IRENE GOYENECHEA 2 1 Instituto Tecnológico Agropecuario de Hidalgo, Apartado Postal 94, Carretera Huejutla- Chalahuiyapa km 5.5, Huejutla de Reyes, Hidalgo, México, C.P. 43000 2 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Hidalgo, Apartado Postal 1-69 Plaza Juárez Pachuca, Hidalgo, México C.P. 42000 (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: We report the karyotype of Sceloporus macdougallii, a lizard endemic to the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, member of the torquatus group. The results confirm a constant chromosomal number for members of the torquatus group within Sceloporus, which is 2n = 32 for females and 2n = 31 for males. This karyotype may be fixed in the “crevice-user” groups of Sceloporus but there are three remaining species in the torquatus group that need to be karyotyped for confirmation. Key words: karyotype, Oaxaca, Phrynosomatidae, Sceloporus macdougallii. Resumen: El cariotipo de Sceloporus macdougallii (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae). – Se presenta el cariotipo de Sceloporus macdougallii, lagartija endémica del estado de Oaxaca, México que pertenece al grupo torquatus. Los resultados obtenidos confirman un número cromosómico constante para el grupo torquatus dentro de Sceloporus, que es 2n = 32 para hembras y 2n = 31 para machos. Este cariotipo parece estar fijado en los grupos de Sceloporus que utilizan grietas, sin embargo hace falta analizar el cariotipo de otras tres especies -

Ecology of Sceloporus Gadsdeni (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae) from the Central Chihuahuan Desert, Mexico

Phyllomedusa 17(2):181–193, 2018 © 2018 Universidade de São Paulo - ESALQ ISSN 1519-1397 (print) / ISSN 2316-9079 (online) doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v17i2p181-193 Ecology of Sceloporus gadsdeni (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae) from the central Chihuahuan Desert, Mexico Héctor Gadsden,1 Gamaliel Castañeda,2 Rodolfo A. Huitrón-Ramírez,2 Sergio A. Zapata- Aguilera,2 Sergio Ruíz,1 and Geoffrey R. Smith3 1 Instituto de Ecología, A. C.-Centro Regional del Bajío, Av. Lázaro Cárdenas 253, A. P. 386, C. P. 61600, Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, México. E-mail: [email protected]. 2 Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Av. Universidad s/n, Fraccionamiento Filadelfa, Gómez Palacio, 35070, Durango, México. 3 Department of Biology, Denison University, Granville, Ohio, USA. Abstract Ecology of Sceloporus gadsdeni (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae) from the central Chihuahuan Desert, Mexico. Populations of Sceloporus cyanostictus Axtell and Axtell, 1971 from southwestern Coahuila have been described as a new species, Sceloporus gadsdeni Castañeda-Gaytán and Díaz-Cárdenas, 2017. Sceloporus cyanostictus is listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List due to the decline in its habitat and its limited distribution. The subdivision of S. cyanostictus into two species further reduces the range and population size of each taxon, thereby posing a possible threat to the conservation status of each species. We describe here the sexual dimorphism, growth, age, population structure, sex ratio, density, and thermal ecology of S. gadsdeni to supplement the available information for one these two species. Males are larger than females, and when both sexes reach maturity after 1.1 yr, they have snout–vent lengths of about 60 mm.