Sceloporus Jarrovii)By Chiggers and Malaria in the Chiricahua Mountains, Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico

Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Kansas Biological Survey Report #151 Kelly Kindscher, Randy Jennings, William Norris, and Roland Shook September 8, 2008 Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico Cover Photo: The Gila River in New Mexico. Photo by Kelly Kindscher, September 2006. Kelly Kindscher, Associate Scientist, Kansas Biological Survey, University of Kansas, 2101 Constant Avenue, Lawrence, KS 66047, Email: [email protected] Randy Jennings, Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] William Norris, Associate Professor, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Roland Shook, Emeritus Professor, Biology, Department of Natural Sciences, Western New Mexico University, PO Box 680, 1000 W. College Ave., Silver City, NM 88062, Email: [email protected] Citation: Kindscher, K., R. Jennings, W. Norris, and R. Shook. Birds, Reptiles, Amphibians, Vascular Plants, and Habitat in the Gila River Riparian Zone in Southwestern New Mexico. Open-File Report No. 151. Kansas Biological Survey, Lawrence, KS. ii + 42 pp. Abstract During 2006 and 2007 our research crews collected data on plants, vegetation, birds, reptiles, and amphibians at 49 sites along the Gila River in southwest New Mexico from upstream of the Gila Cliff Dwellings on the Middle and West Forks of the Gila to sites below the town of Red Rock, New Mexico. -

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus Poinsettii

856.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus poinsettii Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Webb, R.G. 2008. Sceloporus poinsettii. Sceloporus poinsettii Baird and Girard Crevice Spiny Lizard Sceloporus poinsettii Baird and Girard 1852:126. Type-locality, “Rio San Pedro of the Rio Grande del Norte, and the province of Sonora,” restricted to either the southern part of the Big Burro Moun- tains or the vicinity of Santa Rita, Grant County, New Mexico by Webb (1988). Lectotype, National Figure 1. Adult male Sceloporus poinsettii poinsettii (UTEP Museum of Natural History (USNM) 2952 (subse- 8714) from the Magdalena Mountains, Socorro County, quently recataloged as USNM 292580), adult New Mexico (photo by author). male, collected by John H. Clark in company with Col. James D. Graham during his tenure with the U.S.-Mexican Boundary Commission in late Au- gust 1851 (examined by author). See Remarks. Sceloporus poinsetii: Duméril 1858:547. Lapsus. Tropidolepis poinsetti: Dugès 1869:143. Invalid emendation (see Remarks). Sceloporus torquatus Var. C.: Bocourt 1874:173. Sceloporus poinsetti: Yarrow “1882"[1883]:58. Invalid emendation. S.[celoporus] t.[orquatus] poinsettii: Cope 1885:402. Seloporus poinsettiii: Herrick, Terry, and Herrick 1899:123. Lapsus. Sceloporus torquatus poinsetti: Brown 1903:546. Sceloporus poissetti: Král 1969:187. Lapsus. Figure 2. Adult female Sceloporus poinsettii axtelli (UTEP S.[celoporus] poinssetti: Méndez-De la Cruz and Gu- 11510) from Alamo Mountain (Cornudas Mountains), tiérrez-Mayén 1991:2. Lapsus. Otero County, New Mexico (photo by author). Scelophorus poinsettii: Cloud, Mallouf, Mercado-Al- linger, Hoyt, Kenmotsu, Sanchez, and Madrid 1994:119. Lapsus. Sceloporus poinsetti aureolus: Auth, Smith, Brown, and Lintz 2000:72. -

Preliminary Data on the Age Structure of Phrynocephalus Horvathi in Mount Ararat (Northeastern Anatolia, Turkey)

BIHAREAN BIOLOGIST 6 (2): pp.112-115 ©Biharean Biologist, Oradea, Romania, 2012 Article No.: 121117 http://biozoojournals.3x.ro/bihbiol/index.html Preliminary data on the age structure of Phrynocephalus horvathi in Mount Ararat (Northeastern Anatolia, Turkey) Kerim ÇIÇEK1,*, Meltem KUMAŞ1, Dinçer AYAZ1 and C. Varol TOK2 1. Ege University, Faculty of Science, Biology Department, Zoology Section, Bornova, Izmir, Turkey 2. Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Faculty of Science - Literature, Biology Department, Zoology Section, Terzioğlu Campus, Çanakkale/Turkey. *Corresponding author, K. Çiçek, E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Received: 24. September 2012 / Accepted: 22. October 2012 / Available online: 23. October 2012 / Printed: December 2012 Abstract. In this study, the age structure, growth and longevity of 27 individuals (8 juveniles, 8 males and 11 females) from the Mount Ararat (Iğdır, Turkey) population of Phrynocephalus horvathi were examined with the method of skeletochronology. According to the obtained data, the median age was 3.5 (range= 2-5) for males and 4 (2-5) for females. Both sexes reach sexual maturity after their first hibernation, and no statistically significant difference in age composition was observed between the sexes. According to von Bertalanffy growth curves, asymptotic body length was calculated as 51.29 mm and growth coefficient k - 0.60. Key words: Skeletochronology, growth, longevity, Phrynocephalus horvathi, Northeastern Anatolia. Introduction were measured using dial calipers to the nearest 0.01 mm and re- corded. The genus Phrynocephalus is a core of the Palearctic desert Humerus bones were dissected from specimens, fixed in 70% al- cohol and then washed with distilled water. -

Dunes Sagebrush Lizard Habitat

TECHNICAL NOTES U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE NEW MEXICO September, 2011 BIOLOGY TECHNICAL NOTE NO. 53 CRITERIA FOR BRUSH MANAGEMENT (314) in Lesser Prairie-Chicken and Dunes Sagebrush Lizard Habitat Introduction NRCS policy requires that when providing technical and financial assistance NRCS will recommend only conservation treatments that will avoid or minimize adverse effects, and to the extent practicable, provide long-term benefit to federal candidate species (General Manual 190 Part 410.22(E)(7)). This technical note provides the criteria to ensure that the NRCS practice of Brush Management (314) will avoid or minimize any adverse effects to two Candidate Species for Federal listing: the lesser prairie chicken Tympanuchus pallidicinctus (LEPC), and dunes sagebrush lizard Sceloporus arenicolus (DSL). Species Involved The lesser prairie chicken is a species of prairie grouse native to the southern high plains of the U.S.; including the sandhill rangelands of eastern New Mexico. The dunes sagebrush lizard is native only to a small area of southeastern New Mexico and west Texas, with a habitat range that overlaps the lesser prairie chicken range, but only occurs in the sand dune complexes associated with shinnery oak (Quercus havardii Rydb.). Both species’ habitat includes a component of brush: shinnery oak and/or sand sagebrush (Artemisia filifolia Torr.). See Appendix 1 and 2 for more details on each species. Geographic Area Covered by Technical Note No. 53 encompasses private and state lands within the range that supports the dunes sagebrush lizard and lesser prairie chicken habitat. This includes portions of seven counties in New Mexico: Chaves, Curry, De Baca, Eddy, Lea, Roosevelt, and Quay counties. -

Animal Information Natural Treasures Reptiles (Non-Snakes)

1 Animal Information Natural Treasures Reptiles (Non-Snakes) Table of Contents Red-footed Tortoise…………….………………………………………………………..2 Argentine Black and white Tegu.………………….………………………..……..4 Madagascar Giant Day Gecko.……………………………………….……..………5 Henkel’s Leaf-Tailed Gecko……………………………………………………………6 Panther Chameleon………………………………………………………………………8 Prehensile-tailed Skink………………………………………….……………………..10 Chuckwalla………………………………………………………….……………………….12 Crevice Spiny Lizard……………………………………………………………………..14 Gila Monster……………………………………………..………………………………...15 Dwarf Caiman………….…………………………………………………………………..17 Spotted Turtle……………………………………………………………………………..19 Mexican Beaded Lizard………………………………………………………………..21 Collared Lizard………………………………………………………………………....…23 Red-footed Tortoise Geocheloidis carbonaria 2 John Ball Zoo Habitat – Depending on whether they can be found either in the Natural Treasures Building or outside in the children’s zoo area across from the Budgie Aviary. Individual Animals: 1 Male, 1 Female Male – Morty (Smooth shell) o Age unknown . Records date back to 1985 o Arrived October 11, 2007 o Weight: 8.5lbs Female - Ethel o Age unknown o Arrived June 02, 2011 o Weight: 9.5-10lbs Life Expectancy Insufficient data Statistics Carapace Length – 1.6 feet for males, females tend to be smaller Diet – Frugivore – an animal that mainly eats fruit Wild – Fruit during the wet season and flowers during the dry season o Some soil and fungi Zoo – Salad mix (greens, fruits, veggies) hard boiled eggs, and fish o Fed twice a week Predators Other than humans, there is no information available concerning predators. Habitat Tropical, terrestrial Rainforests and savanna areas. It prefers heavily forested, humid habitats but avoids muddy areas due to low burrowing capacity of these habitats. Region Throughout the South American mainland and North of Argentina. Red-footed Tortoise 3 Geocheloidis carbonaria Reproduction – Polygynous (having more than one female as a mate at a time). -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Sprint Performance of Phrynosomatid Lizards, Measured on a High-Speed Treadmill, Correlates with Hindlimb Length

J. Zool., Lond. (1999) 248, 255±265 # 1999 The Zoological Society of London Printed in the United Kingdom Sprint performance of phrynosomatid lizards, measured on a high-speed treadmill, correlates with hindlimb length Kevin E. Bonine and Theodore Garland, Jr Department of Zoology, University of Wisconsin, 430 Lincoln Drive, Madison, WI 53706-1381, U.S.A. (Accepted 19 September 1998) Abstract We measured sprint performance of phrynosomatid lizards and selected outgroups (n = 27 species). Maximal sprint running speeds were obtained with a new measurement technique, a high-speed treadmill (H.S.T.). Animals were measured at their approximate ®eld-active body temperatures once on both of 2 consecutive days. Within species, individual variation in speed measurements was consistent between trial days and repeatabilities were similar to values reported previously for photocell-timed racetrack measure- ments. Multiple regression with phylogenetically independent contrasts indicates that interspeci®c variation in maximal speed is positively correlated with hindlimb span, but not signi®cantly related to either body mass or body temperature. Among the three phrynosomatid subclades, sand lizards (Uma, Callisaurus, Cophosaurus, Holbrookia) have the highest sprint speeds and longest hindlimbs, horned lizards (Phryno- soma) exhibit the lowest speeds and shortest limbs, and the Sceloporus group (including Uta and Urosaurus) is intermediate in both speed and hindlimb span. Key words: comparative method, lizard, locomotion, morphometrics, phrynosomatidae, sprint speed INTRODUCTION Fig. 1; Montanucci, 1987; de Queiroz, 1992; Wiens & Reeder, 1997) that exhibit large variation in locomotor Evolutionary physiologists and functional morpholo- morphology and performance, behaviour, and ecology gists emphasize the importance of direct measurements (Stebbins, 1985; Conant & Collins, 1991; Garland, 1994; of whole-animal performance (Arnold, 1983; Garland & Miles, 1994a). -

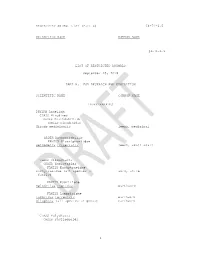

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME §4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS September 25, 2018 PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes -

The San Pedro River in Southeastern Arizona

Lowland Riparian Herpetofaunas: The San Pedro River in Southeastern Arizona Philip C. Rosen School of Natural Resources, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ Abstract—Previous work has shown that southeastern Arizona has a characteristic, high diversity lowland riparian herpetofauna with 62-68 or more species along major stream corridors, and 46-54 species in shorter reaches within single biomes, based on intensive fieldwork and museum record surveys. The San Pedro River supports this characteristic herpetofauna, at least some of which still occurs in the lower basin within the Sonoran Desert. It has about 64 species (55 vouchered to date), with 48-53 species within each of three somewhat ecologically homogeneous portions of the basin. This assemblage is more similar to other lowland herpetofaunas than to an example of a canyon riparian herpetofauna. Most of the characteristic riparian species are not known to be abundant along the San Pedro, and some expected species are apparently absent, suggesting that the herpetofauna may have not yet recovered from the history of grassland, cienega, and bottomland degradation. effort has been most focused in the upper basin, and it is dif- Introduction ficult to entirely separate riparian and non-riparian records, so Remarkably, the riparian herpetofauna of southeastern I have summarized the latter for the upper basin; in the lower Arizona has not been accurately described between Ruthven’s reaches, so little collecting has been done away from the river (1907) and Van Denburgh and Slevin’s (1913) annotations that this was not possible. Museum records were excluded if and records for the Santa Cruz River riparian at Tucson and localities could not be located to an adequate precision, but I the present. -

Amphibians and Reptiles of the State of Coahuila, Mexico, with Comparison with Adjoining States

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 593: 117–137Amphibians (2016) and reptiles of the state of Coahuila, Mexico, with comparison... 117 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.593.8484 CHECKLIST http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research Amphibians and reptiles of the state of Coahuila, Mexico, with comparison with adjoining states Julio A. Lemos-Espinal1, Geoffrey R. Smith2 1 Laboratorio de Ecología-UBIPRO, FES Iztacala UNAM. Avenida los Barrios 1, Los Reyes Iztacala, Tlalnepantla, edo. de México, Mexico – 54090 2 Department of Biology, Denison University, Granville, OH, USA 43023 Corresponding author: Julio A. Lemos-Espinal ([email protected]) Academic editor: A. Herrel | Received 15 March 2016 | Accepted 25 April 2016 | Published 26 May 2016 http://zoobank.org/F70B9F37-0742-486F-9B87-F9E64F993E1E Citation: Lemos-Espinal JA, Smith GR (2016) Amphibians and reptiles of the state of Coahuila, Mexico, with comparison with adjoining statese. ZooKeys 593: 117–137. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.593.8484 Abstract We compiled a checklist of the amphibians and reptiles of the state of Coahuila, Mexico. The list com- prises 133 species (24 amphibians, 109 reptiles), representing 27 families (9 amphibians, 18 reptiles) and 65 genera (16 amphibians, 49 reptiles). Coahuila has a high richness of lizards in the genus Sceloporus. Coahuila has relatively few state endemics, but has several regional endemics. Overlap in the herpetofauna of Coahuila and bordering states is fairly extensive. Of the 132 species of native amphibians and reptiles, eight are listed as Vulnerable, six as Near Threatened, and six as Endangered in the IUCN Red List. In the SEMARNAT listing, 19 species are Subject to Special Protection, 26 are Threatened, and three are in Danger of Extinction. -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus Shannonorum

813.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus shannonorum Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Smith, H.M., E.A. Liner, P. Ponce-Campos, and D. Chiszar. 2006. Sceloporus shannonorum. Sceloporus shannonorum Langebartel Shannon's Spiny Lizard Sceloporus heterolepis Boulenger 1894:724 (part; the syntype British Museum (Natural History) (BMNH) 92.2.8.30 from Rancho La Berberia, Sierra de BolaRos, Jalisco, Mexico). Sceloporus shannonorum Langebartel 1959:25. Type-locality, "37 miles by road from Concordia, Sinaloa, near the Durango-Sinaloa border". Holo- Figure 1. Sceloporus shannonorum from 0.6 km W. type, University of Illinois Museum of Natural His- of Revolcadores, Durango, Mexico. Photograph cour- tory (UIMNH) 43060, adult male, collected by J. tesy of Robert G. Webb. Schaffner, 2 September 1957 (examined by HMS). Sceloporus heterolepis shannonorum: Webb 1969: 305. Sceloporus shannorum: Gilboa 1974:107 (incorrect subsequent spelling). CONTENT. No subspecies are recognized. DEFINITION. A medium-sized species, maximum SVL 78 mm in males, 73 mm in females: at least the lateral scales irregular in size, small ones scattered among larger scales; large dorsolateral nuchal scales sharply differentiated from small lateral nuchal scales, the outer row forming a prominent lateral nuc- ha1 fringe and tuft; dorsals 41-49, mean 45.3; lateral Figure 2. Habitat of Sceloporus shannonorum in scale rows oblique, posteriorly converging dorsally Durango, Mexico. Photograph courtesy of Robert G. almost to midline; femoral pores 13-1 9, mean 15.7; Webb. head scales more or less normal for the genus; two canthals; supraoculars in two rows, scales of medial areas of tiny scales separate two paravertebral rows row much the larger.