Life Before EXCEL: Some Historical Statistical Graphs David Robinson THAMES CANCER REGISTRY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

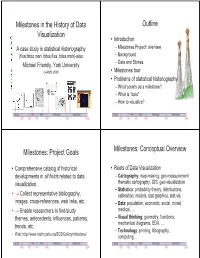

Milestones in the History of Data Visualization

Milestones in the History of Data Outline Visualization • Introduction A case study in statistical historiography – Milestones Project: overview {flea bites man, bites flea, bites man}-wise – Background Michael Friendly, York University – Data and Stories CARME 2003 • Milestones tour • Problems of statistical historiography – What counts as a milestone? – What is “data” – How to visualize? Milestones: Project Goals Milestones: Conceptual Overview • Comprehensive catalog of historical • Roots of Data Visualization developments in all fields related to data – Cartography: map-making, geo-measurement visualization. thematic cartography, GIS, geo-visualization – Statistics: probability theory, distributions, • o Collect representative bibliography, estimation, models, stat-graphics, stat-vis images, cross-references, web links, etc. – Data: population, economic, social, moral, • o Enable researchers to find/study medical, … themes, antecedents, influences, patterns, – Visual thinking: geometry, functions, mechanical diagrams, EDA, … trends, etc. – Technology: printing, lithography, • Web: http://www.math.yorku.ca/SCS/Gallery/milestone/ computing… Milestones: Content Overview Background: Les Albums Every picture has a story – Rod Stewart c. 550 BC: The first world map? (Anaximander of Miletus) • Album de 1669: First graph of a continuous distribution function Statistique (Gaunt's life table)– Christiaan Huygens. Graphique, 1879-99 1801: Pie chart, circle graph - • Les Chevaliers des William Playfair 1782: First topographical map- Albums M. -

An Investigation Into the Graphic Innovations of Geologist Henry T

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche Renee M. Clary Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Clary, Renee M., "Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 127. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/127 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. UNCOVERING STRATA: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE GRAPHIC INNOVATIONS OF GEOLOGIST HENRY T. DE LA BECHE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Renee M. Clary B.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1983 M.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1997 M.Ed., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Renee M. Clary All rights reserved ii Acknowledgments Photographs of the archived documents held in the National Museum of Wales are provided by the museum, and are reproduced with permission. I send a sincere thank you to Mr. Tom Sharpe, Curator, who offered his time and assistance during the research trip to Wales. -

Infovis and Statistical Graphics: Different Goals, Different Looks1

Infovis and Statistical Graphics: Different Goals, Different Looks1 Andrew Gelman2 and Antony Unwin3 20 Jan 2012 Abstract. The importance of graphical displays in statistical practice has been recognized sporadically in the statistical literature over the past century, with wider awareness following Tukey’s Exploratory Data Analysis (1977) and Tufte’s books in the succeeding decades. But statistical graphics still occupies an awkward in-between position: Within statistics, exploratory and graphical methods represent a minor subfield and are not well- integrated with larger themes of modeling and inference. Outside of statistics, infographics (also called information visualization or Infovis) is huge, but their purveyors and enthusiasts appear largely to be uninterested in statistical principles. We present here a set of goals for graphical displays discussed primarily from the statistical point of view and discuss some inherent contradictions in these goals that may be impeding communication between the fields of statistics and Infovis. One of our constructive suggestions, to Infovis practitioners and statisticians alike, is to try not to cram into a single graph what can be better displayed in two or more. We recognize that we offer only one perspective and intend this article to be a starting point for a wide-ranging discussion among graphics designers, statisticians, and users of statistical methods. The purpose of this article is not to criticize but to explore the different goals that lead researchers in different fields to value different aspects of data visualization. Recent decades have seen huge progress in statistical modeling and computing, with statisticians in friendly competition with researchers in applied fields such as psychometrics, econometrics, and more recently machine learning and “data science.” But the field of statistical graphics has suffered relative neglect. -

Reviews Edited by Beth Notzon and Edith Paal

Reviews edited by Beth Notzon and Edith Paal People have been trying to display infor- dull statistician or economist: he dabbled mation graphically ever since our ancestors in fields as varied as engineering, journal- depicted hunts on the cave walls. From ism, and blackmail, the reader discovers. those early efforts through the graphs and There is essentially no limit to the types tables in modern scientific publications, of data display that can be influenced by the attempts have met with various degrees good design, as Wainer makes clear by of success, as Howard Wainer describes in the variety of examples he presents. The Graphic Discovery: A Trout in the Milk and college acceptance letter Wainer’s son Other Visual Adventures. received is cited as a successful display. The This book is no dry, academic tome word “YES,” which is really the only infor- about data. The conversational tone, well- mation the reader cares about in such a chosen illustrations, and enriching asides letter, is printed in large type in the middle combine to create a delightful presentation of the page, with two short, smaller-type of the highlights and lowlights of graphic lines of congratulatory text at the bottom. display. And good data displays will con- As Wainer points out, that tells readers tinue to be important in our current, data- what they want to know without making inundated society. them hunt for it. (He leaves unaddressed Like any good story, this one has its hero. what that school’s rejection letters looked Although writers have used pictures to like that year. -

How Well Can We Equate Test Forms That Are Constructed by Examinees? Program Statistics Research

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 579 TM 024 017 AUTHOR Wainer, Howard; And Others TITLE How Well Can We Equate Test Forms That Are Constructed by Examinees? Program Statistics Research. INSTITUTION Educational Testing Service, Princeton, N.J. REPORT NO ETS-RR-91-57; ETS-TR-91-15 PUB DATE Oct 91 NOTE 29p. PUB TYPE Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adaptive Testing; Chemistry; ComparativeAnalysis; Computer Assisted Testing; *Constructed Response; Difficulty Level; *Equated Scores; *ItemResponse Theory; Models; Selection; Test Format; Testing; *Test Items IDENTIFIERS Advanced Placement Examinations (CEEB); *Unidimensionality (Tests) ABSTRACT When an examination consists, in wholeor in part, of constructed response items, it isa common-practice to allow the examinee to choose amonga variety of questions. This procedure is usually adopted so that the limited number ofitems that can be completed in the allotted time does not unfairlyaffect the examinee. This results in the de facto administrationof several different test forms, where the exact structure ofany particular form is determined by the examinee. When different formsare administered, a canon of good testing practice requires that thoseforms be equated to adjust for differences in their difficulty.When the items are chosen by the examinee, traditional equating proceduresdo not strictly apply. In this paper, how one might equate withan item response theory (IRT) framework is explored. The procedure isillustrated with data from the College Board's Advanced PlacementTest in Chemistry taken by a sample of 18,431 examinees. Comparablescores can be produced in the context of choice to the extent thatresponses may be characterized with a unidimensional IRT model.Seven tables and five figures illustrate the discussion. -

STAT 6560 Graphical Methods

STAT 6560 Graphical Methods Spring Semester 2009 Project One Jessica Anderson Utah State University Department of Mathematics and Statistics 3900 Old Main Hill Logan, UT 84322{3900 CHARLES JOSEPH MINARD (1781-1870) And The Best Statistical Graphic Ever Drawn Citations: How others rate Minard's Flow Map of Napolean's Russian Campaign of 1812 . • \the best statistical graphic ever drawn" - (Tufte (1983), p. 40) • Etienne-Jules Marey said \it defies the pen of the historian in its brutal eloquence" -(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Joseph_Minard) • Howard Wainer nominated it as the \World's Champion Graph" - (Wainer (1997) - http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Joseph_Minard) Brief background • Born on March 27, 1781. • His father taught him to read and write at age 4. • At age 6 he was taught a course on anatomy by a doctor. • Minard was highly interested in engineering, and at age 16 entered a school of engineering to begin his studies. • The first part of his career mostly consisted of teaching and working as a civil engineer. Gradually he became more research oriented and worked on private research thereafter. • By the end of his life, Minard believed he had been the co-inventor of the flow map technique. He wrote he was pleased \at having given birth in my old age to a useful idea..." - (Robinson (1967), p. 104) What was done before Minard? Examples: • Late 1700's: Mathematical and chemical graphs begin to appear. 1 • William Playfair's 1801:(Chart of the National Debt of England). { This line graph shows the increases and decreases of England's national debt from 1699 to 1800. -

Master Thesis SC Final

The Potential Role for Infographics in Science Communication By: Laura Mol (2123177) Biomedical Sciences Master Thesis Communication specialization (9 ECTS) Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam Under supervision of dr. Frank Kupper, Athena Institute, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam November 2011 Cover art: ‘Nonsensical Infograhics’ by Chad Hagen (www.chadhagen.com) "Tell me and I'll forget; show me and I may remember; involve me and I'll understand" - Chinese proverb - 2 Index !"#$%&'$()))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(*! "#!$%&'()*+&,(%())))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(+! ,),! !(#-.%$(-/#$.%0(.1(#'/23'2('.4453/'&$/.3())))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(6! ,)7! 8#/39(/4&92#(/3(#'/23'2('.4453/'&$/.3()))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(:! -#!$%.(/'012,+3()))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(,;! 7),! <3$%.=5'$/.3())))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(,;! 7)7! >/#$.%0()))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(,,! 7)?! @/112%23$(AB2423$#())))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(,:! 7)*! C5%D.#2()))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))(,:! -

Lecture Slides

MTTTS17 Dimensionality Reduction and Visualization Spring 2020 Jaakko Peltonen Lecture 4: Graphical Excellence Slides originally by Francesco Corona 1 Outline Information visualization Edward Tufte The visual display of quantitative information Graphical excellence Data maps Time series Space-time narratives Relational graphics Graphical integrity Distortion in data graphics Design and data variation Visual area and numerical measure 2 Information visualization Data graphics visually display measured quantities by means of the combined use of points, lines, a coordinate system, numbers, words, shading and colour The use of abstract, non-representational pictures to show numbers is a surprisingly recent invention, perhaps because of the diversity of skills required: - visual-artistic, empirical-statistical, and mathematical It was not until 1750-1800 that statistical graphics were invented, long after Cartesian coordinates, logarithms, the calculus, and the basics of probability theory William Playfair (1759-1823) developed/improved upon (nearly) all fundamental graphical designs, seeking to replace conventional tables of numbers with systematic visual representations A Scottish engineer and a political economist The founder of graphical methods of statistics A pioneer of information graphics 3 Information visualization (cont.) Modern data graphics can do much more than simply substitute for statistical tables Graphics are instruments for reasoning about quantitative information Often, the most effi cient way to describe, explore, and summarize -

Notices of the American Mathematical

ISSN 0002-9920 Notices of the American Mathematical Society AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY Graduate Studies in Mathematics Series The volumes in the GSM series are specifically designed as graduate studies texts, but are also suitable for recommended and/or supplemental course reading. With appeal to both students and professors, these texts make ideal independent study resources. The breadth and depth of the series’ coverage make it an ideal acquisition for all academic libraries that of the American Mathematical Society support mathematics programs. al January 2010 Volume 57, Number 1 Training Manual Optimal Control of Partial on Transport Differential Equations and Fluids Theory, Methods and Applications John C. Neu FROM THE GSM SERIES... Fredi Tro˝ltzsch NEW Graduate Studies Graduate Studies in Mathematics in Mathematics Volume 109 Manifolds and Differential Geometry Volume 112 ocietty American Mathematical Society Jeffrey M. Lee, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, American Mathematical Society TX Volume 107; 2009; 671 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 978-0-8218- 4815-9; List US$89; AMS members US$71; Order code GSM/107 Differential Algebraic Topology From Stratifolds to Exotic Spheres Mapping Degree Theory Matthias Kreck, Hausdorff Research Institute for Enrique Outerelo and Jesús M. Ruiz, Mathematics, Bonn, Germany Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain Volume 110; 2010; approximately 215 pages; Hardcover; A co-publication of the AMS and Real Sociedad Matemática ISBN: 978-0-8218-4898-2; List US$55; AMS members US$44; Española (RSME). Order code GSM/110 Volume 108; 2009; 244 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 978-0-8218- 4915-6; List US$62; AMS members US$50; Ricci Flow and the Sphere Theorem The Art of Order code GSM/108 Simon Brendle, Stanford University, CA Mathematics Volume 111; 2010; 176 pages; Hardcover; ISBN: 978-0-8218- page 8 Training Manual on Transport 4938-5; List US$47; AMS members US$38; and Fluids Order code GSM/111 John C. -

Curriculum Vitae for James J. Heckman

September 13, 2021 James Joseph Heckman Department of Economics University of Chicago 1126 East 59th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 Telephone: (773) 702-0634 Fax: (773) 702-8490 Email: [email protected] Personal Date of Birth: April 19, 1944 Place of Birth: Chicago, Illinois Education B.A. 1965 (Math) Colorado College (summa cum laude) M.A. 1968 (Econ) Princeton University Ph.D. 1971 (Econ) Princeton University Dissertation “Three Essays on Household Labor Supply and the Demand for Market Goods.” Sponsors: S. Black, H. Kelejian, A. Rees Graduate and Undergraduate Academic Honors Phi Beta Kappa Woodrow Wilson Fellow NDEA Fellow NIH Fellow Harold Willis Dodds Fellow Post-Graduate Honors Honorary Degrees and Professorships Doctor Honoris Causa, Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria. Jan- uary, 2017. Doctor of Social Sciences Honoris Causa, Lignan University, Hong Kong, China. November, 2015. Honorary Doctorate of Science (Economics), University College London. September, 2013. Doctor Honoris Causis, Pontifical University, Santiago, Chile. August, 2009. Doctor Honoris Causis, University of Montreal.´ May 2004. 1 September 13, 2021 Doctor Honoris Causis, Bard College, May 2004. Doctor Honoris Causis, UAEM, Mexico. January 2003. Doctor Honoris Causis, University of Chile, Fall 2002. Honorary Doctor of Laws, Colorado College, 2001. Honorary Professor, Jinan University, Guangzhou, China, June, 2014. Honorary Professor, Renmin University, P. R. China, June, 2010. Honorary Professor, Beijing Normal University, P. R. China, June, 2010. Honorary Professor, Harbin Institute of Technology, P. R. China, October, 2007. Honorary Professor, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China, 2003. Honorary Professor, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, 2001. Honorary Professor, University of Tucuman, October, 1998. -

STAT 6560 Graphical Methods

STAT 6560 Graphical Methods Spring Semester 2009 Project Work James B. Odei Utah State University Department of Mathematics and Statistics 3900 Old Main Hill Logan, UT 84322{3900 WILLIAM PLAYFAIR (1759-1823) A Graphical Pioneer of the 18th Century Citations: How others rate William Playfair . • \the father of modern graphical display" - (Wainer (2005), p. 5) • \the great pioneer of statistical graphics" - (Playfair (2005), p. v) • \the founder of graphical methods of statistics"-(http://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/William_Playfair) • \the inventor of statistical graphs and writer on political economy" - (Spence (2004), http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/printable/22370) • \the pioneer of information graphics"-(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_ Henry_Playfair) • \an engineer, political economist and scoundrel" - (Spence and Wainer in Statis- ticians of the Centuries, http://bibleproupdate2.com/Definitions/William_ Playfair) • \an ingenious mechanic and miscellaneous writer" - (Eminent Scotsmen, http: //bibleproupdate2.com/Definitions/William_Playfair) Brief background • Born on September 22, 1759. • Was the fourth son of the Reverend James Playfair of the parish of Liff & Benvie near the city of Dundee, Scotland. • Much of his early education was the responsibility of his brother John Playfair (1748-1819), a professor of mathematics and natural philosophy at Edinburgh University. • He pursued variety of careers with such passion, ambition, industry, and optimism that even without his great innovations he would be judged a colorful figure. 1 • He was in turn apprenticed (1774-1747) under Andrew Meikle(inventor of the threshing machine ), millwright to the Rennie family, draftsman for James Watt (inventor of the steam engine), engineer, accountant, inventor, silversmiths, mer- chant, investment broker, economist, statistician, pamphleteer, translator, pub- licist, land speculator, convict, banker, ardent royalist, editor, blackmailer, and journalist. -

No Humble Pie: the Origins and Usage of a Statistical Chart

Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics Winter 2005, Vol. 30, No. 4, pp. 353–368 No Humble Pie: The Origins and Usage of a Statistical Chart Ian Spence University of Toronto William Playfair’s pie chart is more than 200 years old and yet its intellectual ori- gins remain obscure. The inspiration likely derived from the logic diagrams of Llull, Bruno, Leibniz, and Euler, which were familiar to William because of the instruction of his mathematician brother John. The pie chart is broadly popular but—despite its common appeal—most experts have not been seduced, and the academy has advised avoidance; nonetheless, the masses have chosen to ignore this advice. This commentary discusses the origins of the pie chart and the appro- priate uses of the form. Keywords: Bruno, circle chart, Euler, Leibniz, Llull, logic diagrams, pie chart, Playfair 1. Introduction The pie chart is more than two centuries old. The diagram first appeared (Playfair, 1801) as an element of two larger graphical displays (see Figure 1 for one instance) in The Statistical Breviary, whose charts portrayed the areas, populations, and rev- enues of European states. William Playfair had previously devised the bar chart and was first to advocate and popularize the use of the line graph to display time series in statistics (Playfair, 1786). The pie chart was his last major graphical invention. Playfair was an accomplished and talented adapter of the ideas of others, and although we may be confident that we know his sources of inspiration in the case of the bar chart and line graph, the intellectual motivations for the pie chart and its parent, the circle chart, remain obscure.