Demystifying the Art in Spanish Art Song in Late Nineteenth-Century Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

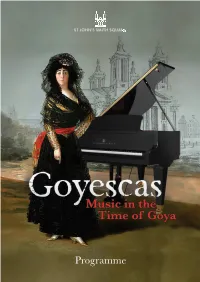

Music in the Time of Goya

Music in the Time of Goya Programme ‘Goyescas’: Music in the Time of Goya Some of the greatest names in classical music support the Iberian and Latin American Music Society with their membership 2 November 2016, 7.00pm José Menor piano Daniel Barenboim The Latin Classical Chamber Orchestra featuring: Argentine pianist, conductor Helen Glaisher-Hernández piano | Elena Jáuregui violin | Evva Mizerska cello Nicole Crespo O’Donoghue violin | Cressida Wislocki viola and ILAMS member with special guest soloists: Nina Corti choreography & castanets Laura Snowden guitar | Christin Wismann soprano Opening address by Jordi Granados This evening the Iberian and Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) pays tribute to one of Spain’s most iconic composers, Enrique Granados (1867–1916) on the centenary year of his death, with a concert programme inspired by Granados’ greatest muse, the great Spanish painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828), staged amidst the Baroque splendour of St John’s Smith Square – a venue which, appropriately, was completed not long before Goya’s birth, in 1728. Enrique Granados To pay homage to Granados here in London also seems especially fi tting given that the great Composer spent his fi nal days on British shores. Granados Will you drowned tragically in the English Channel along with his wife Amparo after their boat, the SS Sussex, was torpedoed by the Germans. At the height of his join them? compositional powers, Granados had been en route to Spain from New York where his opera, Goyescas, had just received its world premiere, and where he had also given a recital for President Woodrow Wilson; in his lifetime Granados was known as much for his virtuoso piano playing as for his talent as a composer. -

Granados: Goyescas

Goyescas Enrique Granados 1. Los Requiebros [9.23] 2. Coloquio en La Reja [10.53] 3. El Fandango de Candil [6.41] 4. Quejas, ó la Maja y el Ruiseñor [6.22] 5. El Amor y la Muerte: Balada [12.43] 6. Epilogo: Serenata del Espectro [7.39] Total Timings [54.00] Ana-Maria Vera piano www.signumrecords.com The Goyescas suite has accompanied me throughout with her during the recording sessions and felt G my life, and I always knew that one day I would generous and grounded like never before. The music attempt to master it.The rich textures and came more easily as my perspectives broadened aspiring harmonies, the unfurling passion and I cared less about perfection. Ironically this is tempered by restraint and unforgiving rhythmic when you stand the best chance of approaching precision, the melancholy offset by ominous, dark your ideals and embracing your audience. humour, the elegance and high drama, the resignation and the hopefulness all speak to my sense of © Ana-Maria Vera, 2008 being a vehicle, offeeling the temperature changes, the ambiguity, and the emotion the way an actor might live the role of a lifetime. And so this particular project has meant more to me than almost any in my career. Catapulted into the limelight as a small child, I performed around the globe for years before realising I had never had a chance to choose a profession for myself. Early success, rather than going to my head, affected my self-confidence as a young adult and I began shying away from interested parties, feeling the attention wasn't deserved and therefore that it must be of the wrong kind. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL CHARACTER AS EXPRESSED IN PIANO LITERATURE Yong Sook Park, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2005 Dissertation directed by: Bradford Gowen, Professor of Music In the middle of the 19th century, many composers living outside of mainstream musical countries such as Germany and France attempted to establish their own musical identity. A typical way of distinguishing themselves from German, French, and Italian composers was to employ the use of folk elements from their native lands. This resulted in a vast amount of piano literature that was rich in national idioms derived from folk traditions. The repertoire reflected many different national styles and trends. Due to the many beautiful, brilliant, virtuosic, and profound ideas that composers infused into these nationalistic works, they took their rightful place in the standard piano repertoire. Depending on the compositional background or style of the individual composers, folk elements were presented in a wide variety of ways. For example, Bartók recorded many short examples collected from the Hungarian countryside and used these melodies to influence his compositional style. Many composers enhanced and expanded piano technique. Liszt, in his Hungarian Rhapsodies, emphasized rhythmic vitality and virtuosic technique in extracting the essence of Hungarian folk themes. Chopin and Szymanowski also made use of rhythmic figurations in their polonaises and mazurkas, often making use of double-dotted rhythms. Obviously, composers made use of nationalistic elements to add to the piano literature and to expand the technique of the piano. This dissertation comprises three piano recitals presenting works of: Isaac Albeniz, Bela Bartók, Frédéric Chopin, Enrique Granados, Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, Frederic Rzewski, Alexander Scriabin, Karol Szymanowski, and Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky. -

Pasodoble PSDB

Documentación técnica Pasodoble PSDB l Pasodoble, o Paso Doble, es un baile que se originó en España entre 1533 y E1538. Podría ser considerado, en esen- cia, como el estandarte sonoro que le distingue en todas partes del mundo. Se trata de un ritmo alegre, pleno de brío, castizo, flamenco unas veces, pero siempre reflejo del garbo y más ge- nuino sabor español. Se trata de una variedad musical dentro de la forma «marcha» en com- pás binario de 2/4 o 6/8 y tiempo «allegro mo- derato», frecuentemente compuesto en tono menor, utilizada indistintamente para desfiles militares y para espectáculos taurinos. Aunque no está del todo claro, parece ser que el pasodoble tiene sus orígenes en la tonadilla escénica, –creada por el flautista es- pañol Luis de Misón en 1727– que era una Este tipo de macha ligera fue adoptada composición que en la primera mitad del siglo como paso reglamentario para la infantería es- XVII servía como conclusión de los entreme- pañola, en la que su marcha está regulada en ses y los bailes escénicos y que después, 120 pasos por minuto, con la característica es- desde mediados del mismo siglo, se utilizaba pecial que hace que la tropa pueda llevar el como intermedio musical entre los actos de las paso ordinario. Tras la etapa puramente militar comedias. –siglo XVIII– vendría la fase de incorporación de elementos populares –siglo XIX–, con la El pasodoble siempre ha estado aso- adición de elementos armónicos de la seguidi- ciado a España y podemos decir que es el baile lla, jota, bolero, flamenco.. -

Crying Across the Ocean: Considering the Origins of Farruca in Argentina Julie Galle Baggenstoss March 22, 2014 the Flamenco

Crying Across the Ocean: Considering the Origins of Farruca in Argentina Julie Galle Baggenstoss March 22, 2014 The flamenco song form farruca is popularly said to be of Celtic origin, with links to cultural traditions in the northern Spanish regions of Galicia and Asturias. However, a closer look at the song’s traits and its development points to another region of origin: Argentina. The theory is supported by an analysis of the song and its interpreters, as well as Spanish society at the time that the song was invented. Various authors agree that the song’s traditional lyrics, shown in Table 1, exhibit the most obvious evidence of the song’s Celtic origin. While the author of the lyrics is not known, the word choice gives some clues about the person who wrote them. The lyrics include the words farruco and a farruca, commonly used outside of Galicia to refer to a person who is from that region of Spain. The use of the word farruco/a indicates that the author was not in Galicia at the time the song was written. Letra tradicional de farruca Una Farruca en Galicia amargamente lloraba porque a la farruca se le había muerto el Farruco que la gaita le tocaba Table 1: Farruca song lyrics Sources say the poetry likely expresses nostalgia for Galicia more than the perspective of a person in Galicia (Ortiz). A large wave of Spanish immigrants settled in what is now called the Southern Cone of South America, including Argentina and Uruguay, during the late 19th century, when the flamenco song farruca was first documented as a sung form of flamenco. -

A La Cubana: Enrique Granados's Cuban Connection

UC Riverside Diagonal: An Ibero-American Music Review Title A la cubana: Enrique Granados’s Cuban Connection Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90b4c4cb Journal Diagonal: An Ibero-American Music Review, 2(1) ISSN 2470-4199 Author de la Torre, Ricardo Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.5070/D82135893 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California A la cubana: Enrique Granados’s Cuban Connection RICARDO DE LA TORRE Abstract Cuba exerted a particular fascination on several generations of Spanish composers. Enrique Granados, himself of Cuban ancestry, was no exception. Even though he never set foot on the island—unlike his friend Isaac Albéniz—his acquaintance with the music of Cuba became manifest in the piano piece A la cubana, his only work with overt references to that country. This article proposes an examination of A la cubana that accounts for the textural and harmonic characteristics of the second part of the piece as a vehicle for Granados to pay homage to the piano danzas of Cuban composer Ignacio Cervantes. Also discussed are similarities between A la cubana and one of Albéniz’s own piano pieces of Caribbean inspiration as well as the context in which the music of then colonial Cuba interacted with that of Spain during Granados’s youth, paying special attention to the relationship between Havana and Catalonia. Keywords: Granados, Ignacio Cervantes, Havana, Catalonia, Isaac Albéniz, Cuban-Spanish musical relations Resumen Varias generaciones de compositores españoles sintieron una fascinación particular por Cuba. Enrique Granados, de ascendencia cubana, no fue la excepción. -

Clair De Lune

A New Type of Musical Coherence Module 17 of Music: Under the Hood John Hooker Carnegie Mellon University Osher Course August 2017 1 Outline • Nationalism in music • Biography of Claude Debussy • Analysis of Clair de lune 2 Nationalism in Music • Rise of ethic consciousness and nationalism – Late 19th century – Rooted in colonialism and development of the concept of “a culture.” • As described by new field of cultural anthropology. • Whence self-conscious “national culture.” • Remains with us today, for better or worse. 3 Nationalism in Music • Rise of ethic consciousness and nationalism – Led to nationalistic styles in music • During late Romantic era • Often inspired by rejection of “development” • …and rejection of German domination of music scene. 4 Nationalism in Music • Some nationalistic schools – Scandinavian • Edvard Grieg, Norway (1843-1907) • Carl Nielsen, Denmark (1865-1931) • Jan Sibelius, Finland (1865-1957) Nielsen Grieg Sibelius 5 Nationalism in Music • Some nationalistic schools – French • Georges Bizet (1838-1875) • Claude Debussy (1862-1918) • Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) • Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) Ravel 6 Bizet Saint-Saëns Nationalism in Music • Some nationalistic schools – German • Richard Wagner (1838-1875) 7 Nationalism in Music • Some nationalistic schools – Russian • Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) • The “Russian Five” – Mily Balakirev (1837-1910) They took an – Cesár Cui (1835-1918) oath to avoid – Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881) Rimsky-Korsakov development – Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908) in their -

El Repertori Els Intèrprets 10 Anys De Festival (2005-2014) La Geografia I

MÚSICS CATALANS A AMÈRICA 10 anys de Festival (2005-2014) de Vicente López; música de Parera-Esnaola; arreglado y anotado por Juan Serpentini. 2a ed. rev. y amp. con instrucciones para su correcta enseñanza. I EL BARCELONA FESTIVAL OF SONG Buenos Aires: Juan Serpentini, [1929?]. (*) Documents cedits per Patricia Caicedo per a l’exposició. TOP 2001-Fol-C 4/68 * Retrats de Montserrat Campmany, Theodoro Valcárcel i Heitor Villalobos. El Barcelona Festival of Song té com a missió * Lied art songs of Latin America. Patricia Caicedo, soprano ; Pau Casan, piano. Fons Montserrat Campany preservar i promoure internacionalment el gènere B.: A. Moraleda, 2000. * Retrat de Manuel Blancafort amb Frederic Mompou. vocal i el treball dels compositors contemporanis en TOP CD 3390 Fons Frederic Mompou * A mi ciudad nativa = to my native city: art songs of Latin America vol. II. * Retrat de Jaume Pahissa i retrat de Ricard Viñes amb Enric Granados. l’àmbit ibèric i llatinoamericà. Està dedicat a l’estudi Patricia Caicedo [soprano]; Eugenia Gassull [piano]. [S.l.]: Mundo Arts, 2005. Fons Joaquim Pena de la història i la interpretació del seu repertori TOP CD 5584 *Suárez Urtubey, Pola. Alberto Ginastera en cinco movimientos. Buenos (*) 2005 Barcelona Festival of Song presents... Aires: Victor Leru, cop. 1972. líric, que du a terme a través de cursos, concerts i * La Canción artística en América Latina: antología crítica y guía interpretativa TOP 2010-8-22192 connexions simultànies amb altres seus. La Biblioteca para cantantes. Prólogo, investigación, revisión y edición Patricia Caicedo. *Toldrà, Eduard. Integral de cant i piano= complete voice & piano works. -

Guitar Music

GUITAR NEWS The Official Organ of the INTERNATIONAL CLASSIC GUITAR ASSOCIATION No. 59 Single cop,y price 1/4 (U.S.A. 20c.) M AY/ J UNE, 196 1 Photo : Natasha Bellow IDA PRESTI, ALEXANDRE LAGOYA, ALEXANDER BELLOW 2 GUITAR NEWS MAY- J U NE, 1961 G. RICORDI & co. Publishers - Milano Bru:telles - Buenos Aires - London - LOrrach - Mexico - New York - Paris - Sao Paulo - Sydney - Toronto NEW EDITIONS FOR GUITAR By MIGUEL ABLONIZ TRANSCRIPTIONS 129879 J. S. BACH, Fugue (1st Violin Sonata). 129882 J. S. BACH, Two Gavottes (5th 'cello Suite). 129880 J. S. BACH, Sarabande-Double, Bourree-Double (1st Violin Partita). 129347 J. S. BACH, Two Bourrees ('French overture') and March (A. Magdalena's book). 129652 L. van BEETHOVEN, Theme and Variation ('septet'). 129653 G . F. HANDEL, Aria ('Ottone'). 129654 G. F. HANDEL, Sarabande and Variations (Suite XI). 129655 J. P. RAMEAU, Six Menuets. 129349 Two ancient 'Ariettes' by A. Scarlatti and A. Caldara. 130056 J. HAYDN, Minuet (Op. 2, No. 2). 130057 F. MENDELSSOHN, Venetian Barcarole (Op. 19, No. 6). 129348 Three short ancient pieces: Aria by Purcell, Minuet by Clarke, Invention by Stanley. 130059 R. SCHUMANN, Four "Album Leaves": Valzer Op. 124, No. 10. Larghetto Op. 124, No. 13. Danza Fantastica Op. 124, No. 5. Presto Op. 99, No. 2. 129884 A Guitar Anthology of Twel ve Pieces (Purcell, Bach, Mozart, Chopin, de Visee, Gruber, etc.). TWO GUITARS 129350 J. S. BACH, Prelude No. I (48 Preludes and Fugues). 130055 J. S. BACH, Prelude No. 1 ("Six Little Preludes"). 12935 l A. VIVALDI, Aria del vagante ("Juditha triumphans"). -

A Mini-Guide

A MINI-GUIDE The Story . .2 Meet the Cast . .3 What is zarzuela? . .5 Meet the Creator of Little Red . .6 The Composers . .7 Activity: Make your own castanets! . .10 The Story: Bear Hug/Abrazo de oso! Bear Hug/Abrazo de oso! is a bilingual (in two different languages) youth opera and the cast sings in both English and Spanish. It is set in a zoo. The Zookeeper enters the stage while feeding some of his favorite animals including Marla, the koala bear, and Polly the panda bear. He admits that while he loves his job as zookeeper, he’s nervous about the grizzly exhibit next door. Grizzly bears are known to eat meat and he feels less than confident. Polly the panda greets the audience and mentions her love of reading and learning. She hears singing next to her exhibit and meets Bernardo, a very special Spanish brown bear and newest exhibit to the zoo. In fact, the entire zoo is decorated to welcome the newest bear! Bernardo, who has just arrived to the zoo and doesn’t speak much English, is nervous and feels lost. He misses his family. Polly distracts him from his loneliness by playing games like charades, trying to understand her new friend. They come across a locked gate. Polly has always wondered what was on the other side of the zoo and her adventur - ous personality starts the bears on a search for the key and out of their exhibit. The two meet Marla, the zoo’s koala bear. Koalas are actually marsupials—that means Marla isn’t really a bear at all! Koala bears are generally sleepy and like to eat plants such as eucalyptus. -

Cartagena Y El Pasodoble

REVISTA DE INVESTIGACIÓN SOBRE FLAMENCO La madrugá Nº15, Diciembre 2018, ISSN 1989-6042 Cartagena y el pasodoble Benito Martínez del Baño Universidad Complutense de Madrid Enviado: 13-12-2018 Aceptado: 20-12-2018 Resumen El pasodoble es un tipo de composición musical menor con títulos de excepción, páginas musicales de gran factura melódica, fuerza expresiva y estructura perfecta. Muchas de sus composiciones han logrado inmortalizar el nombre de sus autores y el insuperable atractivo de dotar emoción nuestras fiestas, patronales y bravas. Podemos incluirlo como subgénero dentro de la composición zarzuelística, y encontrarlo de muy distintas maneras, como en tiempo de marchas aceleradas, alegres y bulliciosas pasadas del coro por la escena, breves y brillantes introducciones orquestales, también para bandas de música, y finales de cuadro o de acto, incluso con tintes flamencos. Asimismo títulos imprescindibles han sido compuestos en Cartagena y algunas de las más ilustres voces de esta tierra lo han cantado y otras aun lo incluyen en su repertorio. Palabras clave: pasodoble, Cartagena, flamenco, música popular. Abstract The pasodoble is a type of minor musical composition with exceptional titles, musical pages of great melodic design, expressive force and perfect structure. Many of his compositions have managed to immortalize the name of their authors and the insurmountable attraction of giving emotion to our festivities, patronal and brave. We can include it as a subgenre within the zarzuela composition, and find it in very different ways, such as in time of accelerated marches, happy and boisterous past of the choir for the scene, brief and brilliant orchestral introductions, also for bands, and end of picture or act, even with flamenco overtones.