2020 Bolivia Conflict Diagnostic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Print Version (PDF)

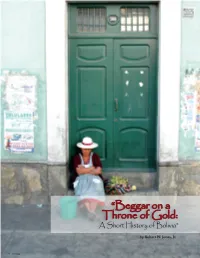

“Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia” by Robert W. Jones, Jr. 6 Veritas is a land of sharp physical and social contrasts. Although blessed with Benormousolivia mineral wealth Bolivia was (and is) one of the poorest nations of Latin America and has been described as a “Beggar on a Throne of Gold.” 1 This article presents a short description of Bolivia as it appeared in 1967 when Che Guevara prepared to export revolution to the center of South America. In Guevara’s estimation, Bolivia was ripe for revolution with its history of instability and a disenfranchised Indian population. This article covers the geography, history, and politics of Bolivia. Geography and Demographics Bolivia’s terrain and people are extremely diverse. Since geography is a primary factor in the distribution of the population, these two aspects of Bolivia will be discussed together. In the 1960s Bolivian society was predominantly rural and Indian unlike the rest of South America. The Indians, primarily Quechua or Aymara, made up between fifty to seventy percent of the population. The three major Indian dialects are Quechua, Aymara, and Guaraní. The remainder of the population were whites and mixed races (called “mestizos”). It is difficult to get an accurate census because The varied geographic regions of Bolivia make it one of the Indians have always been transitory and there are the most climatically diverse countries in South America. cultural sensitivities. Race determines social status in Map by D. Telles. Bolivian society. A mestizo may claim to be white to gain vegetation grows sparser towards the south, where social status, just as an economically successful Indian the terrain is rocky with dry red clay. -

Iv BOLIVIA the Top of the World

iv BOLIVIA The top of the world Bolivia takes the breath away - with its beauty, its geographic and cultural diversity, and its lack of oxygen. From the air, the city of La Paz is first glimpsed between two snowy Andean mountain ranges on either side of a plain; the spread of the joined-up cities of El Alto and La Paz, cradled in a huge canyon, is an unforgettable sight. For passengers landing at the airport, the thinness of the air induces a mixture of dizziness and euphoria. The city's altitude affects newcomers in strange ways, from a mild headache to an inability to get up from bed; everybody, however, finds walking up stairs a serious challenge. The city's airport, in the heart of El Alto (literally 'the high place'), stands at 4000 metres, not far off the height of the highest peak in Europe, Mont Blanc. The peaks towering in the distance are mostly higher than 5000m, and some exceed 6000m in their eternally white glory. Slicing north-south across Bolivia is a series of climatic zones which range from tropical lowlands to tundra and eternal snows. These ecological niches were exploited for thousands of years, until the Spanish invasion in the early sixteenth century, by indigenous communities whose social structure still prevails in a few ethnic groups today: a single community, linked by marriage and customs, might live in two or more separate climes, often several days' journey away from each other on foot, one in the arid high plateau, the other in a temperate valley. -

Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War Roniger, Luis; Senkman, Leonardo

www.ssoar.info Fuel for Conspiracy: Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War Roniger, Luis; Senkman, Leonardo Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Roniger, L., & Senkman, L. (2019). Fuel for Conspiracy: Suspected Imperialist Plots and the Chaco War. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 11(1), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X19843008 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC Lizenz (Namensnennung- This document is made available under a CC BY-NC Licence Nicht-kommerziell) zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu (Attribution-NonCommercial). For more Information see: den CC-Lizenzen finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/deed.de Journal of Politics in j Latin America Research Article Journal of Politics in Latin America 2019, Vol. 11(1) 3–22 Fuel for Conspiracy: ª The Author(s) 2019 Article reuse guidelines: Suspected Imperialist sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/1866802X19843008 Plots and the Chaco War journals.sagepub.com/home/pla Luis Roniger1 and Leonardo Senkman2 Abstract Conspiracy discourse interprets the world as the object of sinister machinations, rife with opaque plots and covert actors. With this frame, the war between Bolivia and Paraguay over the Northern Chaco region (1932–1935) emerges as a paradigmatic conflict that many in the Americas interpreted as resulting from the conspiracy man- oeuvres of foreign oil interests to grab land supposedly rich in oil. At the heart of such interpretation, projected by those critical of the fratricidal war, were partial and extrapolated facts, which sidelined the weight of long-term disputes between these South American countries traumatised by previous international wars resulting in humiliating defeats and territorial losses, and thus prone to welcome warfare to bolster national pride and overcome the memory of past debacles. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO the Politics of Representing the Past in Bolivia a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfa

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Politics of Representing the Past in Bolivia A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Edward Fabian Kennedy Committee in charge: Professor Nancy Grey Postero, Chair Professor Jeffrey Haydu Professor Steven Parish Professor David Pedersen Professor Leon Zamosc 2009 Copyright Edward Fabian Kennedy, 2009 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Edward Fabian Kennedy is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my mother, Maud Roberta Roehl Kennedy. iv EPIGRAPH “Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it. Do not believe in anything simply because it is spoken and rumored by many. Do not believe in anything simply because it is found written in your religious books. Do not believe in anything merely on the authority of your teachers and elders. Do not believe in traditions because they have been handed down for many generations. But after observation and analysis, when you find that anything agrees with reason and is conducive to the good and benefit of one and all, then accept it -

Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of Hist

Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Jocelyn H. Olcott ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Orin Starn ___________________________ Dirk Bönker Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 ABSTRACT Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Jocelyn H. Olcott ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Orin Starn ___________________________ Dirk Bönker An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Elizabeth Shesko 2012 Abstract This dissertation examines the trajectory of military conscription in Bolivia from Liberals’ imposition of this obligation after coming to power in 1899 to the eve of revolution in 1952. Conscription is an ideal fulcrum for understanding the changing balance between state and society because it was central to their relationship during this period. The lens of military service thus alters our understandings of methods of rule, practices of authority, and ideas about citizenship in and belonging to the Bolivian nation. In eliminating the possibility of purchasing replacements and exemptions for tribute-paying Indians, Liberals brought into the barracks both literate men who were formal citizens and the non-citizens who made up the vast majority of the population. -

Unintended Consequences of a Bolivian Quinoa Economy

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2017 From grassroots to global: unintended consequences of a Bolivian quinoa economy Melissa Trinley DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Trinley, Melissa, "From grassroots to global: unintended consequences of a Bolivian quinoa economy" (2017). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 227. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/227 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Grassroots to Global: Unintended Consequences of a Bolivian Quinoa Economy A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts June 9, 2017 BY Melissa Trinley Department of International Studies College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois Copyright @ 2017 Melissa Trinley All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This thesis offers a counterargument to the claims that Bolivian peasant farmers are acting in contradiction with their political support of food sovereignty by participating in a global quinoa economy. This research gives agency to the farmers by reframing the Bolivian quinoa story to show how farmers succeeded in overcoming “development” projects. My research is inspired by two brief periods of time I spent living in Bolivia volunteering with campesinos. -

And the Indigenous People of Bolivia Maral Shoaei University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2012 MAS and the Indigenous People of Bolivia Maral Shoaei University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Latin American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Shoaei, Maral, "MAS and the Indigenous People of Bolivia" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4401 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAS and the Indigenous People of Bolivia by Maral Shoaei A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science College of Arts and Sciences Universtiy of South Florida Major Professor: Bernd Reiter, Ph.D. Rachel May, Ph.D. Harry E. Vanden, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 16, 2012 Keywords: Social Movements, Evo Morales, Cultural Politics, Marginalization and Exclusion Copyright © 2012, Maral Shoaei Acknowledgement I would like to first thank my committee chair, Dr. Bernd Reiter, whose extensive knowledge, expertise and passion for Latin American politics provided me invaluable guidance and support. I have benefited greatly from his enthusiasm and encouragement throughout the research process, and for this I am extremely grateful. I would also like to thank Dr. Rachel May and Dr. Harry Vanden for taking time out to serve as members of my committee and provide me with critical comments, advice and support. -

Pre-Departure Packet Summer 2017 | Bolivia

PRE-DEPARTURE PACKET SUMMER 2017 | BOLIVIA Table of Contents PART I About GESI Welcome (3) Program History (4) Program Information (5) Staff (6) Emergency Contacts (7) GESI Partners (8) Academic Info Experiential Learning (9) Pre-Departure (9) In-Country (10) Final Summit (11) Safety Procedures (12) Preparation Cultural Adjustment (13) Food for Thought (14-16) Works Cited (17) PART II About FSD Letter from FSD (19) About FSD (20-22) Safety Safety (23) Health (24) Visas (25) Logistics Packing List & FAQs (26-27) Electronics (28) Food & Water (29) Communication (30) Money, Flight, Transportation (31-32) Family Homestay (33-35) Personal Account (35) Preparation Cultural Practices at Home & Work (36-37) Race, Sexuality, Gender (38) Language Guide (39) Film & Reading Guides (40-41) Website Guides (42) 2 Welcome Dear GESI Student, Welcome to the 10th annual Global Engagement Studies Institute (GESI)! GESI began with the idea and perseverance of an undergraduate like you. It has since grown from a small experien- tial-learning program in Uganda exclusively for Northwestern students, into a nationally recognized model that has trained and sent over 525 students from almost 100 colleges and universities to 11 countries for community development work. GESI offers students the unique opportunity to apply their classroom learning toward ad- dressing global challenges. Students will spend their time abroad working with, and learning from, our community partners across the world. Northwestern University provides students with compre- hensive preparatory coursework and training, ensures a structured and supported in-country field experience, and facilitates critical post-program reflection. This program will challenge you to think and act differently. -

Bolivia: Political and Economic Developments and Relations with the United States

Order Code RL32580 Bolivia: Political and Economic Developments and Relations with the United States Updated January 26, 2007 Clare M. Ribando Analyst in Latin American Affairs Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Bolivia: Political and Economic Developments and Relations with the United States Summary In the past few years, Bolivia has experienced extreme political unrest resulting in the country having six presidents since 2001. Evo Morales, an indigenous leader of the leftist Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) party, won a convincing victory in the December 18, 2005, presidential election with 54% of the votes. He was inaugurated to a five-year term on January 22, 2006. During his first year in office, President Morales moved to fulfill his campaign promises to decriminalize coca cultivation, nationalize the country’s natural gas industry, and enact land reform. These policies pleased his supporters within Bolivia, but have complicated Bolivia’s relations with some of its neighboring countries, foreign investors, and the United States. Any progress that President Morales has made on advancing his campaign pledges has been overshadowed by an escalating crisis between the MAS government in La Paz and opposition leaders in the country’s wealthy eastern provinces. In August 2006, many Bolivians hoped that the constituent assembly elected in July would be able to carry out constitutional reforms and respond to the eastern province’s ongoing demands for regional autonomy. Five months later, the assembly is stalled, the eastern provinces have held large protests against the Morales government, and clashes between MAS supporters and opposition groups have turned violent. U.S. interest in Bolivia has traditionally centered on its role as a coca producer and its relationship to Colombia and Peru, the two other major coca- and cocaine- producing countries in the Andes. -

Race, Region, and Reconstruction in Nation Building Bolivia Caleb Wittum University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 Making La Ciudad Blanca: Race, Region, and Reconstruction in Nation Building Bolivia Caleb Wittum University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Wittum, .(2015).C Making La Ciudad Blanca: Race, Region, and Reconstruction in Nation Building Bolivia. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3111 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Making La Ciudad Blanca: Race, Region, and Reconstruction in Nation Building Bolivia by Caleb Wittum Bachelor of Arts University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, 2012 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: E. Gabrielle Kuenzli, Director of Thesis Matt D. Childs, Reader Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Caleb Wittum, 2015 All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Prior to the 1899 Federal Revolution, Sucre elite used the memory of Chuquisaca independence exploits to justify their rule and imagine a future for the Bolivian nation. These symbols became widespread in the Bolivian public sphere and were the dominant national discourse for the Bolivian nation. However, dissatisfied highland elite began crafting an alternative national project and these two competing Nationalisms clashed and eventually led to the 1899 Federal Revolution. -

Evaluating Evo Morales: the Conflicts and Convergences of Populism, Resource Nationalism, and Ethno-Environmentalism in Bolivia

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 4-2021 Evaluating Evo Morales: The Conflicts and Convergences of Populism, Resource Nationalism, and Ethno-Environmentalism in Bolivia Gillian Diebold University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Comparative Politics Commons Recommended Citation Diebold, Gillian, "Evaluating Evo Morales: The Conflicts and Convergences of Populism, Resource Nationalism, and Ethno-Environmentalism in Bolivia" 01 April 2021. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/258. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/258 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evaluating Evo Morales: The Conflicts and Convergences of Populism, Resource Nationalism, and Ethno-Environmentalism in Bolivia Abstract This thesis seeks to integrate existing scholarly frameworks of populism, resource nationalism, and ethno-environmentalism in order to create a comprehensive understanding of Morales and the MAS. From 2006 until 2019, President Evo Morales and the Movimiento al socialismo (MAS) led Bolivia to global prominence. Experts lauded Morales and the MAS for apparent development successes and democratic expansion in a nation long known for its chronic poverty and conflict. Still, yb the time of his controversial resignation, several socioenvironmental conflicts had diminished his eputationr as an ethno- environmental champion, revealing the tensions inherent in pursuing resource nationalist development in an ethnopopulist state. While existing scholarship on the subject views populist and resource nationalist strategies and policies separately, their functional convergence in the Isiboro Sécure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS) conflict demonstrates the necessity of an integrated framework. -

The Monetary and Fiscal History of Bolivia, 1960-2017

The Monetary and Fiscal History of Bolivia, 1960–2017 Timothy J. Kehoe University of Minnesota, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, and National Bureau of Economic Research Carlos Gustavo Machicado Institute for Advanced Development Studies (INESAD) José Peres-Cajías Economic History Department, University of Barcelona Staff Report 579 February 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21034/sr.579 Keywords: Bolivia; Monetary policy; Fiscal policy; Hyperinflation; Public enterprises JEL classification: E52, E63, H63, N16 The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. __________________________________________________________________________________________ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis • 90 Hennepin Avenue • Minneapolis, MN 55480-0291 https://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Research Department Staff Report 579 February 2019 First version: August 2010 The Monetary and Fiscal History of Bolivia, 1960–2017* Timothy J. Kehoe University of Minnesota, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, and National Bureau of Economic Research Carlos Gustavo Machicado Institute for Advanced Development Studies (INESAD) José Peres-Cajías Economic History Department, University of Barcelona ABSTRACT___________________________________________________________________ After the economic reforms that followed the National Revolution of the 1950s, Bolivia seemed positioned for sustained growth. Indeed, it achieved unprecedented growth from 1960 to 1977. Mistakes in economic policies, especially the rapid accumulation of debt due to persistent deficits and a fixed exchange rate policy during the 1970s, led to a debt crisis that began in 1977. From 1977 to 1986, Bolivia lost almost all the gains in GDP per capita that it had achieved since 1960. In 1986, Bolivia started to grow again, interrupted only by the financial crisis of 1998–2002, which was the result of a drop in the availability of external financing.