The Governance of Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lagan College Grant Maintained Integrated School 44 Manse Road Age Range: 11-18 Lisnabreeny Admissions No: 200 Belfast Bt8 6Sa Enrolment No: 1300

Admissions criteria for entry September 2019 LAGAN COLLEGE GRANT MAINTAINED INTEGRATED SCHOOL 44 MANSE ROAD AGE RANGE: 11-18 LISNABREENY ADMISSIONS NO: 200 BELFAST BT8 6SA ENROLMENT NO: 1300 Principal: Mrs A McNamee BA, PGCE, MEd, PQH(NI) Telephone No: 028 9040 1810 Chairman Board of Governors: Mr Francis Martin FCA BSSc. Email: [email protected] Dip Acc. MBA FIMC Website: www.lagancollege.com Lagan College is an integrated, all-ability, co-educational school. It has a grammar stream entry and an all-ability entry. OPEN DAY INFORMATION Saturday 12th January 2019 from 9.00am to 12.30pm - The Principal, Mrs McNamee, will address parents at 9.30am, 10.30am and 11.30am in the Hall. To Parents/Guardians naming Lagan College as a preference on your child’s Transfer Form for the Stage I Grammar Stream entry (35% of total Year 8 intake). Entrance Assessment Results Lagan College will consider the outcome of a pupil’s performance in either the GL Assessment or the AQE Assessment for entry into the Stage I Grammar stream entrance route. Please ensure that you attach the following information to your child’s Transfer Form: An original copy of the results issued by AQE or GLA must be attached to the Transfer Form (or both where an applicant has sat both assessments). The candidate number issued to your child by AQE and/or GLA when you registered for the assessment. Special Circumstances and/or Special Provision If you are making a claim for your child to be considered under Special Circumstances or Special Provision you are required to present the documentation requested. -

Committee for Education Minutes of Proceedings 3

Northern Ireland Assembly COMMITTEE FOR EDUCATION Minutes of Proceedings WEDNESDAY 3 March 2021 Video Conference Present by Video Conference: Mr Chris Lyttle MLA (Chairperson) Mr Pat Sheehan MLA (Deputy Chairperson) Mr Maurice Bradley MLA Ms Nicola Brogan MLA Mr Robbie Butler MLA Mr William Humphrey MBE MLA Mr Daniel McCrossan MLA Mr Justin McNulty MLA Mr Robin Newton MBE MLA Apologies: None In Attendance: Ms Aoibhinn Treanor (Assembly Clerk) Mr Mark McQuade (Assistant Clerk) Mr Craig Mealey (Clerical Supervisor) Ms Emma Magee (Clerical Officer) The meeting commenced at 9:04 am in public session. 1. Apologies There were no apologies. 2. Chairperson’s Business 2.1 General Teaching Council for Northern Ireland (GTCNI) The Chairperson reminded members that the Committee agreed to arrange oral briefings with the Department of Education and the General Teaching Council NI on its role, legal vires and stakeholder concerns at its meeting on Wednesday 24 March 2021. Agreed: The Committee agreed to be briefed informally by the Northern Ireland Teachers Council (NITC) on their concerns about GTCNI on 9 March 2021. 2.2 Tabled items The Committee noted correspondence from the Department in regard to school restart and exams; covid-19 vulnerable children plan benchmarking, vaccination and pandemic learning; the recruitment arrangements for a chairperson, vice- chairperson and panel member of the imminent New Decade New Approach Review of Education, which are unregulated appointments; and notification of the termination of the Transformation programme; for discussion with the Minister on 10 March. 2.3 Recent announcements The Chairperson informed members of the publication of the Department’s Emotional Health and Wellbeing Framework and of the Teachers’ Pay settlement. -

NICIE Newsletter Summer 2015

Summer 2015 Integratededucation NICIE welcomes integrated institution, a number of practical status for Loughries PS steps will be taken by the staff and Governors including changes In This Issue... The Northern Ireland Council for to the Governing body, a review of Integrated Education (NICIE) is the curriculum programmes including RE and staff training and delighted at the Education Minister, NICIE Welcomes Integrated John O’Dowd’s decision to approve development.Loughries Integrated Status For Loughries PS the transformation to integrated Primary School will continue to Response to Ministerial status of Loughries PS in the greater serve children of all faiths and Decision on Mallusk Primary School Newtownards area. none in Loughries, and will NICIE Welcomes Continuing Post Demand for an integrated primary provide for the first time integrated Primary Integrated Education In Crumlin school in the wider Newtownards provision for those residing within NICIE News—Meetings area has grown and since the the Greater Ards area. IIEW 2016 successful ballot, Loughries PS has APTIS, VPIn Forum This Issue...and ISFA been working closely with NICIE to Both Sides Now develop and implement a School Trips comprehensive transformation Integrated School News action plan and will continue to do Roundup so now approval has been given. Diana Awards In order to ensure that the school Killyleagh PS Development becomes a fully integrated Proposal Dates for your diary Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education www.nicie.org https://www.facebook.com/niciebelfast 25 College Gardens, Belfast, BT9 6BS Tel. 02890 972910 Fax. 02890 972919 [email protected] https://twitter.com/niciebelfast Response to Ministerial Decision on Mallusk Primary School The Principal and Governors of Mallusk Primary School and The Grange of Mallusk Steering Group welcome the Minister’s decision to allow Mallusk Primary School to transform to Controlled Integrated status. -

Post-Primary Inspection (Involving Action Short of Strike)

Education and Training Inspectorate POST-PRIMARY INSPECTION Lagan College, Belfast Integrated, co-educational, 11-18 all-ability school DE Ref No (426-0255) Report of an Inspection (Involving Action Short of Strike) in February 2019 CONTENTS Section Page 1. Context 1 2. Pupils’, parents’ and staff questionnaire responses 1 3. Focus of the inspection 2 4. Overall findings of the inspection 2 5. Outcomes for learners 2 6. Quality of provision 3 7. Leadership and management 4 8. Safeguarding 5 9. Overall effectiveness 5 Appendices A. Examination performance and other statistical data B. Inspection methodology and evidence base C. Reporting terms used by the Education and Training Inspectorate INTRODUCTION 1. Context Lagan College draws its pupils from around fifty primary schools and is consistently oversubscribed. A bilateral admissions system operates, with around 35% of the pupils entering the school through academic selection. The approval of a development proposal in 2017 led to an increase in enrolment in the sixth form and there are currently 278 pupils studying a variety of courses at this stage. The school community benefits from a new school building, which opened in 2013. Lagan College is an active member of a number of partnerships including the Northern Ireland Council for Integrated Education and the east Belfast learning community. The school is engaged in shared education work with two other post-primary schools. Four of the teaching unions, which make up the Northern Ireland Teachers’ Council (NITC), have declared industrial action primarily in relation to a pay dispute. This includes non-co-operation with the Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI). -

LAGAN COLLEGE BELFAST Drugs Policy Policy Reviewed – November 2017 – Principal and Vice Principal

LAGAN COLLEGE BELFAST Drugs Policy Policy Reviewed – November 2017 – Principal and Vice Principal Document Reviewed: March 2018 by D Collins, VP Pastoral Date Ratified by BOG: February 2017 Review Date: August 2018 Related Documents 1. LCB Positive Behaviour Policy 2. LCB Use of Reasonable Force Policy 3. CCEA Drugs Guidance for Schools in Northern Ireland 4. DENI Circular 2015/23 – Drugs Guidance 5. DENI Circular 2014/25 – Encouraging a smoke‐free and e‐cigarette free environment in schools and youth organisations RATIONALE Lagan College’s Drug Education Policy complies with its statutory obligation to have a drugs policy. The policy follows the Department of Education Circular 2015/23 and the guidance given by the CCEA in the Northern Ireland Curriculum Drugs Guidance for Schools in Northern Ireland (Revised Edition 2015) (referred to in this Policy as "the CCEA Drugs Guidance"). Lagan College recognises that young people in today’s society are exposed to the risks associated with the drug culture which exists. Young people are challenged by the changing and sometimes conflicting values of society, which places demands on them to make informed and responsible choices. The school wishes to promote the development of the ‘whole person’ which encompasses physical, spiritual, mental, emotional, social and environmental health; by equipping students with the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values to handle their lives effectively in the present and prepare them for adulthood. Research cites personal inadequacy, a lack of self‐esteem and peer pressure as the main reasons for drug misuse among young people. This places a responsibility on the school to ‘better prepare young people for adult life.’ (Education Reform (NI) Order 1989) Our school believes that the misuse of drugs endangers not only our students but also affects the wider community in which we live. -

Eco-Schools Newsletter Eco-Schools 20Th Anniversary Event Celebration

Like Tweet Eco-Schools Newsletter Welcome to the Eco-Schools Northern Ireland April 2015 Newsletter. Eco-Schools 20th Anniversary Event Celebration. We were delighted to welcome almost 2000 school teachers and pupils to our 20th Anniversary Event last month. The turn-out represented 10% of schools within Northern Ireland and goes a long way to show the commitment of schools involved in the programme. The day included awards, speeches, workshops, exhibits and performances and was an amazing day enjoyed by everyone who attended. We would like to thank the following organisations for their kind support of the Eco-Schools 20th Anniversary Event: SSE Airtricity, the principal sponsors of Eco-Schools in Northern Ireland and ambassador for the Energy topic; the Department of the Environment; Magherafelt District Council; Cookstown Textile Recyclers, Eco-Schools waste topic sponsors; the Wrigley Company Foundation, Eco-Schools Litter topic sponsors; Translink, Eco-Schools Transport topic sponsors; and Trócaire, Eco-Schools Global Perspective topic sponsors who all attended to help celebrate the day. We were also delighted to have Event sponsorship from: ni4kids the local media outlet which is full of information for parents of school-aged children. They presented an Ambassador Eco-School award to Downpatrick Nursery School and provided copies of the latest edition of their magazine. Bank of Ireland Junk Kouture in association with Repak is an exciting recycled fashion competition which challenges secondary school students from across Ireland to create wearable couture fashion from rubbish. They presented a fabulous fashion show on the day and presented an Ambassador Eco-School award to Lagan College. -

Lagan College School Development Plan

LAGAN COLLEGE SCHOOL DEVELOPMENT PLAN ! Academic Years 2019-2022 Edition 1 2019-20 Contents Section 1 Ethos and Values Page Section 2: A Provision for Learning Planning Page Teaching and Learning Page Curriculum Provision Page Sixth Form Provision Page Provision for E Learning & E Safety (G) Page B Provision for Learning B Additional Educational Needs Page C Provision for Pastoral Care & Wellbeing Promoting Health & Wellbeing Page Safeguarding and Child Protection Page Attendance Page Positive Behaviour Page D/E Provision for Staff Professional Development & Wellbeing Professional Development Page Attendance Page Health & Wellbeing Page F Provision for Learning via Partnerships CEIAG Page Links and Partnerships Page Extra Curricular Provisions Page Equality of Opportunity Page Shared Education & CRED Page East Belfast Area Learning Community Page 2 International Links Page Eco School Page STEM Page Section 3 A/B Finance & Resources Public Value Page Physical Resources and Accommodation Page Section 4 Achievements, Standards, and Progress Student Progress GCSE Page Student Progress GCE Page Standards Page Progress Page Statutory Key Targets Page Section 5 Challenges Page Opportunities Page Section 6 Consulting & Preparing the New SIP Page Section 7 School Improvement Action Plans Page Appendices Page Consultation Documents Page 3 Lagan College Section 1 1 Integrated Ethos & Values Summary Lagan College was founded in 1981 with 28 students as Northern Ireland’s first planned integrated school. Today there are 1386 students including 285 in the Sixth Form and the College continues to be well over-subscribed. As the flagship of integrated education, the central aim of Governors, Principal and staff is: ‘to educate to the highest standards Catholics, Protestants, and others of goodwill, of all abilities, together’. -

Lagan College Induction Booklet 2020‐2021

Lagan College Induction Booklet 2020‐2021 0 Principal’s Welcome We are delighted to offer your child a place at Lagan College for September 2020. We appreciate that your child may be excited and nervous about the prospect of moving up to, ‘big school,’ especially as they have been home learning since March. We will do our very best to alleviate their worries and to support all our children returning to Lagan College via an Induction Programme in late August. Please be reassured that we will be adhering to Department of Education and the Education Authority’s guidelines in response to the COVID‐19 emergency. Unfortunately, for the short term we will not be able to offer the following provisions: Morning Assemblies Extra‐Curricular Activities One to One Music Tuition Educational Visits Changing Room Facilities for PE We envisage that all students will be initially asked to bring a packed lunch with the exception of those children who are eligible to receive a free school meal (Please note that we are a single‐use plastic free zone from 1 September 2020). Students will be expected to wear normal school uniform, however, they will be permitted to wear their PE uniform on the day they have PE only. At Lagan College we endeavour to form good relationships with our students and their families. During the academic year 2020 – 2021 we will be utilising Parent Mail, a text messaging and email service with parent(s)/guardian(s) and all of our Social Media sites which include Twitter, Facebook and the School Website, to stay in regular communication with you. -

DP 482 Lagan College-1.Pdf

COPY OF DEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL SUBMISSION Cover Note DP No. 482 School Lagan College Proposal To increase Lagan College’s enrolment number from 1200 to 1300 phased over two years from September 2017, or as soon as possible thereafter, with the school’s admission number remaining at 200. Minister’s Decision *Approve Development Proposal 482. Date of Decision 14 February 2017 Minister’s Comments As above* Additional notes n/a Information redacted Some information and personal data may have been removed in line with the principles of the Freedom of Information and Data Protection Act. Key Details .... redaction * refers to less than five cases where data is considered sensitive # means figure has been suppressed to prevent disclosure of sensitive information under rules of disclosure 1 From: Lorraine Finlay Area Planning Policy Team Date: 13 February 2017 To: PETER WEIR MLA Copy distribution below DEVELOPMENT PROPOSAL NO 482 – LAGAN COLLEGE/INCREASE ENROLMENT Issue: Development Proposal No 482 published 24 November 2016 by the Education Authority on behalf of the Board of Governors of Lagan College to increase the school’s enrolment from 1200 to 1300 (with admissions remaining at 200 places) from September 2017 or as soon as possible thereafter. Timescale: Urgent. The proposed implementation date for this proposal is September 2017. Financial/Resourc Capital Cost: Nil. Lagan College’s new building e Implications: was designed and built to accommodate a sixth form of over 340 places. Funding Requirements: A high-level funding estimate for the implementation of this proposal using 2016-17 Post-Primary Formula Funding values, is £234k (full year 2018-19) and £136k (in-year 2017-18). -

Community Visits in Belfast, Northern Ireland

COMMUNITY VISITS Community Visits in Belfast, Northern Ireland COMMUNITY VISITS – OPTION 1 What: Visit To Cross-community Projects Where: The Inter Community Development Project, Belfast Conflict Resolution Consortium, Mount Vernon Community Development Forum When: Friday 5 February 1000 – 1300 THE INTER COMMUNITY Development Project The Inter Community Development Project, Intercomm, was established in 1995 as the result of growing community concerns about the lack of formal structures to deal with political and sectarian unrest in the absence of meaningful intercommunity contact in the North Belfast area. Intercomm is driven by a fundamental ethos of co-operation and partnership. Founded in 1995 by community activists Liam Maskey and Billy Mitchell, the project’s core aim is to forge fruitful links between Catholic/ Nationalist and Protestant/ Unionist community groups through long term strategic development work, community inspired peace building initiatives, youth programmes and job creation programmes. The cornerstone of Intercomm’s peace building strategy is most importantly the people of North Belfast. Those who have intimately experienced the effects of conflict are the key resource in the project’s aim to transcend community division through dialogue. The Peace Building Programme, as a means of community empowerment, is a pioneering programme which intends to enhance the peacebuilding skills of community workers through informed discussion and debate, assessment of good practice and international experience of conflict resolution. It is an innovative venture combining workshops, seminars, skills training and field trips, with a vision to build capacity within the community for conflicts to be managed and resolved without violence in accordance with universally agreed standards and practices. -

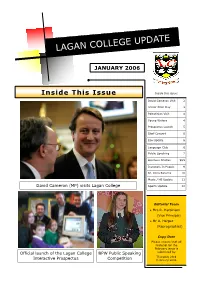

Lagan College Update Jan 2006

E LEGE UPDAT LAGAN COL JANUARY 2006 Inside This Issue Inside this issue: David Cameron Visit 2 Senior Prize Day 3 Palestinian Visit 4 Young Writers 4 Prospectus Launch 5 Staff Concert 6 Eco Update 6 Language Club 6 Public Speaking 7 Business Studies 8&9 Investors In People 9 Sr. Anne Returns 10 Music / HE Update 11 David Cameron (MP) visits Lagan College Sports Update 12 Editorial Team • Mrs R. Harbinson (Vice Principal) • Mr A. Harper (Reprographics) Copy Date Please ensure that all material for the February issue is Official launch of the Lagan College BPW Public Speaking submitted by Thursday 23rd Interactive Prospectus Competition February 2006 LAGAN COLLEGE UPDATE P AGE 2 David Cameron (MP) Visit Lagan College was delighted to welcome the Conservative Party Leader, Mr David Cameron, to the College in December 2005 It was Mr Cameron’s first visit to Northern Ireland and he was thrilled with the reception he received from Lagan College Students. David Cameron meeting the Board of David Cameron joins in with the school choir Governors on his arrival who sang “When The Sun Comes Up” David Cameron overlooking a Technology & David Cameron answering students Design class at work questions in a Politics class David Cameron engaged in a debate with the David Cameron with staff and Board of Justice Group Governors LAGAN COLLEGE UPDATE P AGE 3 Senior Prize Day Lagan College was delighted to welcome back past students to Senior Prize Giving on 19th December 2005. Ciara Murray was awarded the President’s Plate and Bursary Award. This is a new Bursary Award for the College and was kindly bestowed and presented by Dr Jill McIvor, wife of the late Rt. -

Post Primary Guide 2021

Ulster Tatler POST PRIMARY GUIDE 2021 Campbell College // Rockport // Clongowes Wood College // Victoria College Belfast // Grosvenor Grammar School // Bloomfield Collegiate School // St Columbanus’ College // Wellington College // Lagan College // Cookstown High School // The Royal Belfast Academical Institute // Ballyclare High School // Assumption Grammar // Ashfield Girls’ High School // St Joesph’s College // Banbridge Academy // University of Aberdeen // Liverpool John Moores University STRIP ADVERT POST PRIMARY GUIDE 2021 CONTENTS A MESSAGE 000 A FROM 000 A 000 A 000 A EDUCATION 000 A 000 A 000 A MINISTER 000 A 000 A 000 A PETER 000 A 000 A 000 A WEIR 000 A 000 A 000 A Join our 000 A 000 A 000 A Virtual 000 A 000 A 000 A Open Month 000 A 000 A I AM PROUD OF OUR 000 A “ 000 A REPUTATION AS A REGION From Saturday THAT OFFERS A FIRST-CLASS 6th February 2021 EDUCATION SYSTEM THAT PLACES NI VERY FIRMLY ON THE INTERNATIONAL STAGE.” Boarding Places Available very year children face the exciting The pandemic has impacted many that offers a first-class education system prospect of moving from primary aspects of educational life. Many children that places Northern Ireland very firmly Eschool to ‘big school’. I clearly in Northern Ireland are undertaking one or on the international stage. My aspiration remember my sense of excitement and both transfer tests this month. This will be is that each and every young person anticipation at the prospect of leaving the followed by the anxious wait to see if they is nurtured and encouraged to realise friendly and familiar surroundings of my have been successful in gaining entry into their full potential and progress to further first school.