BACKGROUND and RECOMMENDATIONS for Rural CODE REFORM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Niger Valley Development Programme Summary of the Updated Environmental and Social Impact Assessment

Kandadji Ecosystems Regeneration and Niger Valley Development Programme Summary of the Updated Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Language: English Original: French AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP PROJECT TO SUPPORT THE KANDADJI ECOSYSTEMS REGENERATION AND NIGER VALLEY DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME (P_KRESMIN) COUNTRY: NIGER SUMMARY OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Mohamed Aly BABAH Team Leader RDGW2/BBFO 6107 Principal Irrigation Engineer Aimée BELLA-CORBIN Chief Expert, Environmental and Social SNSC 3206 Protection Expert Nathalie G. GAHUNGA RDGW.2 3381 Chief Gender Expert Gisèle BELEM, Senior Expert, Environmental and Social SNSC 4597 Protection Team Members Parfaite KOFFI SNSC Consulting Environmentalist Rokhayatou SARR SAMB Project Team SNFI.1 4365 Procurement Expert Eric NGODE SNFI.2 Financial Management Expert Thomas Akoetivi KOUBLENOU RDGW.2 Consulting Agroeconomist Sector Manager e Patrick AGBOMA AHAI.2 1540 Sector Director Martin FREGENE AHAI 5586 Regional Director Marie Laure. AKIN-OLUGBADE RDWG 7778 Country Manager Nouridine KANE-DIA CONE 3344 Manager, Regional Mouldi TARHOUNI RDGW.2 2235 Agricultural Division Page 1 Kandadji Ecosystems Regeneration and Niger Valley Development Programme Summary of the Updated Environmental and Social Impact Assessment SUMMARY OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) Project Name : Project to Support the Kandadji Ecosystems SAP Code: P-NE-AA0-020 Regeneration and Niger Valley Development Programme Country : NIGER Category : 1 Department : RDGW Division : RDGW.2 1. INTRODUCTION Almost entirely located in the Sahel-Saharan zone, the Republic of Niger is characterised by very low annual rainfall and long dry spells. The western part of country is traversed by the Niger River, which is Niger’s most important surface water resource. -

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

12 Flood Risk Preliminary Mapping in Niamey, Niger33

Maurizio Tiepolo31 and Sarah Braccio32 12 Flood Risk Preliminary Mapping in Niamey, Niger33 Abstract: Flood mapping is still rare in the large cities South of Sahara. The lack of information on the characteristics of floods, the orography of the sites and the recep- tors hampers its production. However, even with scant information, it is possible to create preliminary risk mapping. This tool can be used by local administrations in decision making on emergency plans or on climate change (CC) action plans. From 2010 onwards, the River Niger at Niamey (1.1 million inhabitants, 123 km2 in 2014) swelled at unseasonal times. This new river flood pattern can be linked to CC. Each flooding event affected thousands of people and homes. The steady development of areas that did not appear to be flood prone in the past is the main cause of these impacts. These areas require special measures if further impact is to be avoided in the future. This chapter presents the preliminary flood risk map of Niamey 1:20,000. The map was built up using an historic approach (flooded area derived from satellite images) and considering risk (R) as the result of hazard (H) and damage (D), R = H * D. Risk was measured according to two scenarios: medium and high probability of flooding. The inverse of the return period of river and pluvial flooding (H) and the potential damage to buildings and crops according the water depth were used. Infor- mation to measure risk components was sourced by daily rainfall and daily discharge of the River Niger from 1946 to 2014, and from high-resolution satellite images (2014). -

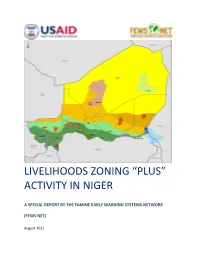

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

Human Rights Watch

350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: +1-212-290-4700 Fax: +1-212-736-1300; 917-591-3452 Washington, April 9, 2021 Ministers Dr. Boubakar Hassan and Alkassoum Indattou, A frica Division Mausi Segun, Executive Director Niamey, Republic of Niger Ida Sawyer, Deputy Director Carine Kaneza Nantulya, Advocacy Director Re: Alleged abuses in Tillabéri and Tahoua regions Laetitia Bader, Horn Director Corinne Dufka, Associate Director, Sahel Dewa Mavhinga, Associate Director, Southern Africa Dear Ministers Hassan and Indattou: Lewis Mudge, Central Africa Director Otsieno Namwaya, East Africa Director Najma Abdi, Coordinator I write on behalf of Human Rights Watch, a nongovernmental human Ilaria Allegrozzi, Senior Researcher Aoife Croucher, Associate rights organization that documents and reports on abuses by states and Clémentine de Montjoye, Researcher non-state armed groups in over 100 countries. Congratulations on your Carine Dikiefu Banona, Assistant Researcher Anietie Ewang, Researcher recent appointments as Ministers of Justice and National Defense. Thomas Fessy, Senior Researcher Zenaida Machado, Senior Researcher Tanya Magaisa, Associate Oryem Nyeko, Researcher As you take up the work of your respective ministries, we wish to share Mohamed Osman, Assistant Researcher Nyagoah Tut Pur, Researcher the serious allegations of extrajudicial killings and enforced Jean-Sébastien Sépulchre, Officer Jim Wormington, Senior Researcher disappearances by armed Islamists and the government security forces in the Tillabéri and Tahoua regions that we have gathered since October A f r i c a Advisory Committee 2019 and urge you to establish an independent and impartial Joy Ngozi Ezeilo, Co-chair Joel Motley, Co-chair investigations into these apparent crimes. -

July, 1984 USAID, Niamey NIGER IRRIGATION SUBSECTOR

NIGER IRRIGATION SUBSECTOR ASSESSMENT VOLUME ONE MAIN REPORT July, 1984 Glenn Anders, Irrigation Engineer USAID, Niamey Walter Firestone, Agronomist Michael Gould, Environmental Specialist Emile Malek, Public Health Specialist Emmy Simmons, arming Systems Economist Malcolm Versel, Vegetable Marketing Teresa Ware, Institutional Analyst Tom Zalla, Team Leader NIGER IRRIGATION SUB-SECTOR A.SSESSMENT Table of Contents Paae EXECUTIV.E S==",R L.. .......... i i. INTRODU2 0N...... ................. II. GOVERNMENT AND DONOR ACTIVITIES RELATED TO IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE ...... ........... 2 A. Government of Niger Institutions ....... 2 1, Ministrv of Rqal Development (MDR) . 2 2. Ministry of Hydrology and the Environment (AHE) ........... 3 3. Ministry of Higher Education and Research (MESR) ...... ............ 4 B. Donor Activities ....... ............. 4 III. IRRIGATION SYSTEMS IN NIGER .... ........ 5 A. Jointly Managed River Pumping Systems . 6 B. Jointly Managed Surface Dam Systems . 6 C. Jointly Managed Ground Water Pumping Systems ........................ 7 D. Individual Managed Micro-Irrigation Systems ......... ................. 7 IV. ENGINEERING ASPECTS OF IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE IN NIGER .......... .................. 8 A. Factors Influencing Development Costs . 9 1. Topography ........ ............... 9 2. Design Standards... ............ 11 3. Competition ..... .............. 12 4. Risk and Uncertainty... .......... .. 12 B. Water Supply and Management Problems. 13 C. System Maintenance. ............... 14 D. Feasibility of Promoting -

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT NIGER Prepared by the Arid Lands

Draft Environmental Report on Niger Item Type text; Book; Report Authors Speece, Mark; University of Arizona. Arid Lands Information Center. Publisher U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat, Department of State (Washington, D.C.) Download date 24/09/2021 16:15:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/227914 DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT ON NIGER prepared by the Arid Lands Information Center Office of Arid Lands Studies University of Arizona Tucson, Arizona 85721 National Park Service Contract No. CX- 0001 -0 -0003 with U.S. Man and the Biosphere Secretariat Department of State Washington, D.C. September 1980 DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT ON NIGER Table of Contents Summary 1.0 GeneralInformation 1 1.1 Preface 1 1.2 Geography and Climate 2 1.2.1The Northern Highlands 2 1.2.2 Northern Deserts 3 1.2.3 The Southern Agricultural Zone 3 1.3 Demographic Characteristics 3 1.3.1Population 3 1.3.2Composition 4 1.3.3 Migration and Urbanization 5 1.3.4 Public Health 5 1.4 Economic Characteristics 7 1.4.1Agriculture and Livestock 7 1.4.2Other Sectors 8 1.4.3 Foreign Aid 8 2.0 Natural Resources 9 2.1 Mineral Resources and Energy 9 2.1.1Mineral Policy 11 2.1.2 Energy 12 2.2 Water 13 2.2.1 Surface Water 13 2.2.2 Groundwater 15 2.2.3 Water Use 16 2.2.4 Water Law 17 2.3 Soils and Agricultural Land Use 18 2.3.1 Soils 18 2.3.2 Agriculture 23 2.4 Vegetation 27 2.4.1 Forestry 32 2.4.2 Pastoralism 33 2.5 Fauna and Protected Areas 36 2.5.1 Endangered Species 38 2.5.2 Fishing 38 3.0Major Environmental Problems 39 3.1 Drought 39 3.2 Desertification 40 3.3 Deforestation and Devegetation 42 3.4 Soil Erosion and Degradation 42 3.5 Water 43 4.0Development 45 Literature Cited 47 Appendix I Geography 53 Appendix II Demographic Characteristics 61 Appendix III Economic Characteristics 77 Appendix IVList of U.S. -

Final Evaluation of Imagine Project

FINAL EVALUATION OF IMAGINE PROJECT Consultants: Abagi Sidi Idriss Issa Bawa Mme Abdoul Baki Baraka Adamou Niamey, August 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 6 A. Context of the evaluation .................................................................................................................... 6 B. Objectives of the evaluation................................................................................................................ 6 C. Methodology of the evaluation............................................................................................................ 7 II. PRESENTATION OF THE IMAGINE PROJECT ........................................................................ 8 A. Technical elaboration of the project.................................................................................................... 8 B. Relevance of the IMAGINE project.................................................................................................... 9 C. Project Funding Arrangements.......................................................................................................... 10 III. PROJECT REALIZATIONS AND EFFECTIVENESS............................................................... 12 A. Increase access to education, particularly for girls............................................................................ 12 1) The realizations of component n°1 .............................................................................................. -

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique Au Niger»

«Fichier Electoral Biométrique au Niger» DIFEB, le 16 Août 2019 SOMMAIRE CEV Plan de déploiement Détails Zone 1 Détails Zone 2 Avantages/Limites CEV Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote CEV: Centre d’Enrôlement et de Vote Notion apparue avec l’introduction de la Biométrie dans le système électoral nigérien. ▪ Avec l’utilisation de matériels sensible (fragile et lourd), difficile de faire de maison en maison pour un recensement, C’est l’emplacement physique où se rendront les populations pour leur inscription sur la Liste Electorale Biométrique (LEB) dans une localité donnée. Pour ne pas désorienter les gens, le CEV servira aussi de lieu de vote pour les élections à venir. Ainsi, le CEV contiendra un ou plusieurs bureaux de vote selon le nombre de personnes enrôlées dans le centre et conformément aux dispositions de création de bureaux de vote (Art 79 code électoral) COLLECTE DES INFORMATIONS SUR LES CEV Création d’une fiche d’identification de CEV; Formation des acteurs locaux (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil) pour le remplissage de la fiche; Remplissage des fiches dans les communes (maire ou son représentant, responsable d’état civil et 3 personnes ressources); Centralisation et traitement des fiches par commune; Validation des CEV avec les acteurs locaux (Traitement des erreurs sur place) Liste définitive par commune NOMBRE DE CEV PAR REGION Région Nombre de CEV AGADEZ 765 TAHOUA 3372 DOSSO 2398 TILLABERY 3742 18 400 DIFFA 912 MARADI 3241 ZINDER 3788 NIAMEY 182 ETRANGER 247 TOTAL 18 647 Plan de Déploiement Plan de Déploiement couvrir tous les 18 647 CEV : Sur une superficie de 1 267 000 km2 Avec une population électorale attendue de 9 751 462 Et 3 500 kits (3000 kits fixes et 500 tablettes) ❖ KIT = Valise d’enrôlement constitués de plusieurs composants (PC ou Tablette, lecteur d’empreintes digitales, appareil photo, capteur de signature, scanner, etc…) Le pays est divisé en 2 zones d’intervention (4 régions chacune) et chaque région en 5 aires. -

Cadernos De Museologia Nº 28 – 2007 191

CADERNOS DE MUSEOLOGIA Nº 28 – 2007 191 PROJET DE REALIZATION D´UN ECO MUSE (KASSAI GORIA) DE WANZERBE (NIGER) Ong Zaka Faba PORTEUR DU PROJET :Mme HAIDARA 1. PRESENTATION DU MILIEU DU PROJET GENERALITES Le Niger est un pays sahélien situé au sud du Sahara en Afrique de l’ouest. Il couvre une superficie de 1267 000 km2 dont les 2 / 3 sont désertiques, il est limité au Nord par l’Algérie et la Libye, au Sud par le Nigeria et le Bénin, à l’Est par le Tchad et à l’Ouest par le Mali et le Burkina faso. Le climat est caractérisé par trois saisons : saison froide (novembre – février), saison chaude (mars – mai) et une saison pluvieuse (juin –septembre.) Les précipitations varient du Nord au Sud avec un isomètre évoluant respectivement de 5O mm à 800 mm sur une période de un à trois mois. Cette irrégularité des précipitations influe grandement sur la production agricole dans un pays essentiellement à vocation agro-pastorale. Sa population est estimée à 12 000 000 d’habitants environ selon le Recensement Administratif 2004 est composée de 9 ethnies réparties dans les huit régions du pays. CADERNOS DE MUSEOLOGIA Nº 28 – 2007 192 PRESENTATION DE LA REGION Le Département de Téra est situé dans la partie ouest du Niger dans la Région de Tillabéry. Il couvre une superficie de 20 220 Km2. Téra, chef lieu du Département est à 177 km de Niamey. La population de ce Département estimée à 413 887 habitants est essentiellement agricole et majoritairement peuplée de Sonrhaï agriculteurs sédentaires possédant du bétail. -

Niger Education and Community Strengthening (NECS) Quarterly Narrative Report No

Niger Education and Community Strengthening (NECS) Quarterly Narrative Report No. 4, April - June 2013 And Year 1 Annual Report 1 Table of Contents List of Accronyms …………………………………………………………………...…. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………..….... 4 Context of Implementation ………………………………………………………...….... 4 I. General Overview …………………………………………………….......… 7 a. Political & Security Situation……………………………………...….… 7 b. Key Program Highlights ……………………………………….…...…... 8 II. Current Quarter Activities ……………………………………….……..…... 8 a. Strategic Objective 1: Increase access to quality education at project schools. …………………………………………………………………. 8 b. Strategic Objective 2 : Increased student grade reading achievement ... 18 c. Monitoring and Evaluation ……………………………………………. 20 III. Quarterly Financial Report (April-June 2013) ……………………………. 22 IV. Next Quarter Commitments and Expenditures ………………….……….... 22 V. Activities Planned for Next Quarter …………………………….………… 22 2 LIST OF ACRONYMS AeA Aide et Action AME Students’ Mothers Association ANED Nigerian Association for Education and Development AOR Agreement Officer Representative APE Students’ Parents Association (equivalent to PTA) CGDES School Management Committees (Used to be called COGES) COP Chief of Party CRC Child Right Convention DGEB Direction Générale de l’Enseignement de Base DPSF Directorate for the Promotion of Education of Girls DREN Regional Directos of Education EGRA Early Grade Reading Association EIE Initial Environmental Evaluation EMMP Environmental Measures and Mitigation Plan FCC Communal -

NIGER - Reference Map

NIGER - Reference Map L I B Y A N A R A B J A M A H I R I Y A ! Tamanrasset 0 100 200 km ! Madama Legend !Djado National capital !Zouar Regional capital Populated place A L G E R I A ! Séguedine International boundary Region boundary I-n-Guezzâm ! Aney ! AGADEZ ! Elevation (meters) Assamakka !Iferouane ! 2,500 - 3,000 Dirkou ! 2,000 - 2,500 ! Arlit 1,500 - 2,000 Bilma ! 1,000 - 1,500 Akokan Fachi 800 - 1,000 ! ! Timia 600 - 800 !Elmeki 400 - 600 ! M A L I !Tabelot Tiguidan Tessoum Aoudouras 200 - 400 ! 0 - 200 Tchirozerine ! ! Dabaga k a ! Below sea level u o a Tchimoumounene Tchintaborak z !! Agadez Disclaimer: The designations employed and the ’A l presentation of material on this map do not e Ingall d imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever é e l on the part of the Secretariat of the United l a Nations concerning the legal status of any V country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, Ménaka or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or ! Tchin Tabaraden N I G E R boundaries. Map data sources: CGIAR, United ! DIFFA Nations Cartographic Section, ESRI, FAO, zar A Government of Niger, Natural Earth. Aderbissinat ! Abalak ! TAHOUA ! Termit-Kaoboul N'gourty ! o s s Takanamat o ! Bani Bangou! C H A D B l Tahoua o ! ZINDER l Ayorou l ! Tamaske Tânout ! a ! D ! Bankila!ré TILLABÉRI Sanam !Bagaroua Belbeji Keita ! ! Sabon Rafi Mehanna Illéla ! ! ! Dakoro ! !Ouallam !Filingué Bouza ! Djiambala Bakin-birji N'guigmi ! ! ! Damagaram Taker Mao Téra! Madawa ! Dargol Fandou ! Bonkoukou ! ! ! Tillabéri Galmi Dankori Bo!uti ! Mayaki