What Are Statues Good For? Winning the Battle Or Losing the Battleground?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pretoria Student Law Review (2019) 13

PRETORIA STUDENT LAW REVIEW (2019) 13 Pretoria Tydskrif vir Regstudente Kgatišobaka ya Baithuti ba Molao ya Pretoria Editor-in-chief: Primrose Egnetor Ruvarashe Kurasha Editors: Thato Petrus Maruapula Mzwandile Ngidi Frieda Shifotoka 2019 (2019) 13 Pretoria Student Law Review Published by: Pretoria University Law Press (PULP) The Pretoria University Law Press (PULP) is a publisher, based in Africa, launched and managed by the Centre for Human Rights and the Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, South Africa. PULP endeavours to publish and make available innovative, high-quality scholarly texts on law in Africa. PULP also publishes a series of collections of legal documents related to public law in Africa, as well as text books from African countries other than South Africa. For more information on PULP, see www.pulp.up.ac.za Printed and bound by: Minit Print, Hatfield, Pretoria Cover: Design by Adebayo Okeowo To submit articles, contact: PULP Faculty of Law University of Pretoria South Africa 0002 Tel: +27 12 420 4948 Fax: +27 12 362 5125 [email protected] www.pulp.up.ac.za ISSN: 1998-0280 © 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Editors’ note: Legacy v by Primrose Egnetor Ruvarashe Kurasha Tribute v ii Note on contributions viii Restoring electricity use with the spoliation remedy: A critical comment on Eskom Holdings Soc Ltd v Masinda 1 by Gustav Muller Prescription: The present interpretation of extinctive prescription and the acquisition of real rights 17 by Celinhlanhla Magubane To be black and alive: A study of the inherent racism in the tertiary education system in post-1994 South Africa 27 by Chelsea L. -

Rhodes Fallen: Student Activism in Post-Apartheid South Africa

History in the Making Volume 10 Article 11 January 2017 Rhodes Fallen: Student Activism in Post-Apartheid South Africa Amanda Castro CSUSB Angela Tate CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Castro, Amanda and Tate, Angela (2017) "Rhodes Fallen: Student Activism in Post-Apartheid South Africa," History in the Making: Vol. 10 , Article 11. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol10/iss1/11 This History in the Making is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. History in the Making Rhodes Fallen: Student Activism in Post-Apartheid South Africa By Amanda Castro and Angela Tate The Cecil Rhodes statue as a contested space. Photo courtesy of BBC News.1 In early March of 2015, the steely gaze of Cecil Rhodes—ardent imperialist, founder of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia), and former Prime Minister of the Cape Colony—surveyed the campus of the University of Cape Town (UCT) through a splatter of feces. It had been collected by student Chumani Maxwele from “one of the portable toilets that dot the often turbulent, crowded townships on the windswept plains outside Cape Town.”2 Maxwele’s actions sparked a campus-wide conversation that spread to other campuses in South Africa. They also joined the global conversations about Black Lives Matter; the demands in the United States to remove Confederate flags and commemorations to Confederate heroes, and the names of racists (including President 1 Andrew Harding, “Cecil Rhodes Monument: A Necessary Anger?,” BBC News, April 11, 2015, accessed March 3, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/ world-africa-32248605. -

A Comparative Study of Zimbabwe and South Africa

FACEBOOK, YOUTH AND POLITICAL ACTION: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ZIMBABWE AND SOUTH AFRICA A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MEDIA STUDIES, RHODES UNIVERSITY by Admire Mare September 2015 ABSTRACT This comparative multi-sited study examines how, why and when politically engaged youths in distinctive national and social movement contexts use Facebook to facilitate political activism. As part of the research objectives, this study is concerned with investigating how and why youth activists in Zimbabwe and South Africa use the popular corporate social network site for political purposes. The study explores the discursive interactions and micro- politics of participation which plays out on selected Facebook groups and pages. It also examines the extent to which the selected Facebook pages and groups can be considered as alternative spaces for political activism. It also documents and analyses the various kinds of political discourses (described here as digital hidden transcripts) which are circulated by Zimbabwean and South African youth activists on Facebook fan pages and groups. Methodologically, this study adopts a predominantly qualitative research design although it also draws on quantitative data in terms of levels of interaction on Facebook groups and pages. Consequently, this study engages in data triangulation which allows me to make sense of how and why politically engaged youths from a range of six social movements in Zimbabwe and South Africa use Facebook for political action. In terms of data collection techniques, the study deploys social media ethnography (online participant observation), qualitative content analysis and in-depth interviews. -

Rhodesmustfall: Using Social Media to “Decolonise” Learning Spaces for South African Higher Education Institutions: a Cultural Historical Activity Theory Approach

#RHODESMUSTFALL: USING SOCIAL MEDIA TO “DECOLONISE” LEARNING SPACES FOR SOUTH AFRICAN HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS: A CULTURAL HISTORICAL ACTIVITY THEORY APPROACH S. Francis* e-mail: [email protected] J. Hardman* e-mail: [email protected] *School of Education University of Cape Town Cape Town, South Africa ABSTRACT Since the end of 2015, South African universities have been the stage of ongoing student protests that seek to shift the status quo of Higher Education Institutes through calls to decolonise the curriculum and enable free access to HEIs for all. One tool that students have increasingly turned to, to voice their opinions has been social media. In this article we argue that one can use Cultural Historical Activity Theory to understand how the activity systems of the traditional academy are shifting the wake of social media, with traditional power relations becoming more porous as students’ voices gain an audience. By tracing the historical development of CHAT, we show how 4th generation CHAT enables us to analyse potential power shifts in HEIs brought about through the use of social media. Keywords: decolonising the curriculum Higher Education, cultural historical activity theory INTRODUCTION 2015 was rife with controversy in South Africa, but it was an exciting time as important conversations around access to higher education, the inclusivity of South African universities and decolonisation became part of public conversation (Kamanzi 2015; Hlophe 2015; Masondo 2015). This movement became known under the hashtag of #Rhodesmustfall, indicating the need to decolonise academic spaces felt by those in the movement. In subsequent years this movement has transformed into #feesmustfall, indicating the students’ driving motive to gain access to institutes of higher learning. -

TV on the Afrikaans Cinematic Film Industry, C.1976-C.1986

Competing Audio-visual Industries: A business history of the influence of SABC- TV on the Afrikaans cinematic film industry, c.1976-c.1986 by Coenraad Johannes Coetzee Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art and Sciences (History) in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Dr Anton Ehlers December 2017 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za THESIS DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2017 Copyright © 2017 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS Historical research frequently requires investigations that have ethical dimensions. Although not to the same extent as in medical experimentation, for example, the social sciences do entail addressing ethical considerations. This research is conducted at the University of Stellenbosch and, as such, must be managed according to the institution’s Framework Policy for the Assurance and Promotion of Ethically Accountable Research at Stellenbosch University. The policy stipulates that all accumulated data must be used for academic purposes exclusively. This study relies on social sources and ensures that the university’s policy on the values and principles of non-maleficence, scientific validity and integrity is followed. All participating oral sources were informed on the objectives of the study, the nature of the interviews (such as the use of a tape recorder) and the relevance of their involvement. -

The Black Sash, Vol. 16, No. 7

The Black Sash, Vol. 16, No. 7 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org/. Page 1 of 41 Alternative title The Black SashThe Black Sash Author/Creator The Black Sash (Johannesburg) Contributor Duncan, Sheena Publisher The Black Sash (Johannesburg) Date 1973-11 Resource type Journals (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1973 Source Digital Imaging South Africa (DISA) Relation The Black Sash (1956-1969); continued by Sash (1969-1994) Rights By kind permission of Black Sash. Format extent 39 page(s) (length/size) Page 2 of 41 SASHVol. 16. No. 7Nov. 1973Price: 40cThe Black Sash magazine Page 3 of 41 BLACK SASH OFFICE BEARERSIlEADQUARTERSNational President: Mrs. -

Tracing Objects of Measurement: Locating Intersections of Race, Science and Politics at Stellenbosch University

TRACING OBJECTS OF MEASUREMENT: LOCATING INTERSECTIONS OF RACE, SCIENCE AND POLITICS AT STELLENBOSCH UNIVERSITY Handri Walters Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Social Anthropology in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Professor Kees (C.S.) van der Waal Co-Supervisor: Professor Steven Robins March 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT This study departs from a confrontation with a collection of ‘scientific’ objects employed at Stellenbosch University in various ways from 1925 to 1984. Eugen Fischer’s Haarfarbentafel (hair colour table), Rudolf Martin’s Augenfarbentafel (eye colour table) and Felix von Luschan’s Hautfarbentafel (skin colour table) - a collection later joined by an anatomically prepared human skull - are employed in this study as vessels for -

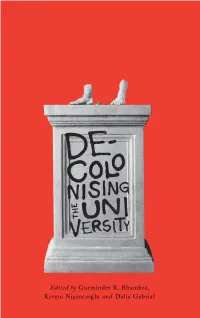

Decolonising the University

Decolonising the University Decolonising the University Edited by Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu First published 2018 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu 2018 The right of the individual contributors to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3821 7 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3820 0 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7868 0315 3 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0317 7 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7868 0316 0 EPUB eBook This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America Bhambra.indd 4 29/08/2018 17:13 Contents 1 Introduction: Decolonising the University? 1 Gurminder K. Bhambra, Dalia Gebrial and Kerem Nişancıoğlu PART I CONTEXTS: HISTORICAL AND DISCPLINARY 2 Rhodes Must Fall: Oxford and Movements for Change 19 Dalia Gebrial 3 Race and the Neoliberal University: Lessons from the Public University 37 John Holmwood 4 Black/Academia 53 Robbie Shilliam 5 Decolonising Philosophy 64 Nelson Maldonado-Torres, Rafael Vizcaíno, Jasmine Wallace and Jeong Eun Annabel We PART II INSTITUTIONAL INITIATIVES 6 Asylum University: Re-situating Knowledge-exchange along Cross-border Positionalities 93 Kolar Aparna and Olivier Kramsch 7 Diversity or Decolonisation? Researching Diversity at the University of Amsterdam 108 Rosalba Icaza and Rolando Vázquez 8 The Challenge for Black Studies in the Neoliberal University 129 Kehinde Andrews 9 Open Initiatives for Decolonising the Curriculum 145 Pat Lockley vi . -

1 Rhodes Must Fall: Archives and Counter-Archives Cynthia Kros

Rhodes Must Fall: Archives and Counter-Archives Cynthia Kros Research Associate, Wits History Workshop and Research Associate, Capital Cities Programme, University of Pretoria Email address: [email protected] Abstract This article takes its departure point from the fact that the VIADUCT 2015 platform overlapped chronologically with the “Rhodes Must Fall” campaign at the University of Cape Town (UCT). I ask whether bringing some of the archival theory that was discussed and applied at the platform to bear on an analysis of the campaign against the statue of Rhodes at UCT – in conjunction with the existing literature around monuments – is helpful in deepening understandings of the campaign. After singling out some of the most interesting literature on monuments and monumental iconoclasm, I explore the ways in which Derridean and Foucauldian inspired readings of the archive might be applied to the colonial memorial landscape. I propose that the campaign was sustained both by a substantial archive of iconoclasm, and that the protesters consciously tried to extend and elaborate on the archive/counter-archive. Keywords Rhodes, monuments, memorials, iconoclasm, photographic tropes, visual archive Introduction My article is inspired by the recent “Rhodes Must Fall” (hereafter “RMF”) campaign at the University of Cape Town (UCT), which culminated in the removal of the statue of notorious mining magnate and British imperialist Cecil John Rhodes from the campus on the 9th of April 2015. The VIADUCT 2015 platform entitled “Archival addresses: photographies, practices, positionalities” convened by the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre at the University of Johannesburg (18-20 March) was contemporaneous with the UCT campaign, and has prompted a reading of it through the multifocal lenses of archive and counter- archive offered by VIADUCT participants. -

Former SRC President Offers His Views on the Protest Conversation

Date: 16 March 2016 Letter to my generation: A juncture towards conversation I thought of writing to you some time ago, but the prevailing circumstances at universities offered no opportunity for me to do so. This piece of writing serves primarily to elevate a number of issues that seem to have escaped the prevailing conversations both nationally and institutionally. I write to you reluctantly owing to having earlier in the year taken a position to provisionally retire from writing publicly so as to critically reflect on the past year. I am well aware that after the publication of this letter, I may very well lose favour in the eyes of several comrades. Unfortunately, the aversion of critic by political formation is a permanent unavoidable feature of politics. Please regard the contents of this letter as my own views. I do not claim to speak on behalf of any political formation. The deficiency of current political discourse I find that we often read history out of context. Our current political situation is not only centered on coloniser versus the colonised axis but incorporates other struggles which were silenced in the past. This introduces a certain degree of complexity both in the articulation and contemporary practice of grassroots politics particularly on campuses. The annunciation and centering of black pain fails dismally to give expression to the different narratives of pain felt by the black community. The ‘white, male, cisgender, heterosexual, able-bodied, Judaeo-Christian faith, European, capitalist…’ body has been placed in front of the jury and is accused of colossal ethical and human rights violations upon an aboriginal population. -

“Rhodes Must Fall”: Student Activism and the Politics of Memory At

1 “RHODES MUST FALL”: STUDENT ACTIVISM AND THE POLITICS OF MEMORY AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN, SOUTH AFRICA By: Chrislyn Laurie Laurore Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Anthropology Mount Holyoke College South Hadley, Massachusetts April 2016 2 Table of Contents: I. Part One: The Problem of Memory Acknowledgements …3 Preface …6 Introduction: Imagining Cape Town …12 Chapter 1 The Man Behind the Statue: Rhodes in South Africa …18 Chapter 2 Remembering Rhodes …40 II. Part Two: Reclaiming Memory Chapter 3 The Revolution Will Be Retweeted: Mobilizing and Memorializing the Movement through Social Media …58 Chapter 4 Constructing Identity through the Performance of Protest …83 Chapter 5 Reimaging South Africa …93 Conclusion …97 Bibliography …100 3 Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to offer my most heartfelt thanks to my thesis advisor, Professor Andrew Lass. Your guidance, encouragement, and support throughout every step of this project has been immaterial. Thank you for reminding me to enjoy the process and teaching me that messiness and imperfection are okay. You may just get me to call you Andy, yet. To the additional readers on this thesis committee, Professors Lynn Morgan and Kimberly Brown: thank you. You have been the greatest inspiration to me and so many other Mount Holyoke students. Thank you for your patience and for joining me on this journey of learning. I would also like to thank my pal over at the SAW Center (and dear friend since our fateful critical social thought first-year seminar with Professor Pleshakov), Khadija Ahmed, for listening to me ramble on about this research and helping me organize my thoughts into something resembling coherency. -

University of Cape Town

Town Cape of University Sartorial Disruption An investigation of the histories, dispositions, and related museum practices of the dress/fashion collections at Iziko Museums as a means to re-imagine and re-frame the sartorial in the museum. Erica de Greef The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derivedTown from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of African Studies University of Cape Town January 2019 “Clothes are people to Diana Vreeland. Her interest in them is deep and human” (Ballard, 1960:293, cited in Clark, De la Haye & Horsley. 2014:26) This text represents a full and original submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Cape Town. This copy has been supplied for the purpose of research, on the understanding that it is copyright material, and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgment. Cover Image: SAM14268: Beadwork Detail. Photograph by Andrew Juries, Courtesy of Andrew Juries. iii iv Abstract In this thesis I investigate and interrogate the historical and current compositions, conditions and dispositions of three collections containing sartorial objects of three formerly separate museums – the South African Museum, the South African National Gallery and the South African Cultural History Museum.