Pablo Sarasate and His Stradivari Violins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edouard Lalo Symphonie Espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Edouard Lalo Born January 27, 1823, Lille, France. Died April 22, 1892, Paris, France. Symphonie espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21 Lalo composed the Symphonie espagnole in 1874 for the violinist Pablo de Sarasate, who introduced the work in Paris on February 7, 1875. The score calls for solo violin and an orchestra consisting of two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, triangle, snare drum, harp, and strings. Performance time is approximately thirty-one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lalo's Symphonie espagnole were given at the Auditorium Theatre on April 20 and 21, 1900, with Leopold Kramer as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Bizet's Carmen is often thought to have ignited the French fascination with all things Spanish, but Edouard Lalo got there first. His Symphonie espagnole—a Spanish symphony that's really more of a concerto—was premiered in Paris by the virtuoso Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate the month before Carmen opened at the Opéra-Comique. And although Carmen wasn't an immediate success (Bizet, who died shortly after the premiere, didn't live to see it achieve great popularity), the Symphonie espagnole quickly became an international hit. It's still Lalo's best-known piece by a wide margin, just as Carmeneventually became Bizet's signature work. Although the surname Lalo is of Spanish origin, Lalo came by his French first name (not to mention his middle names, Victoire Antoine) naturally. His family had been settled in Flanders and in northern France since the sixteenth century. -

Franco-Belgian Violin School: on the Rela- Tionship Between Violin Pedagogy and Compositional Practice Convegno Festival Paganiniano Di Carro 2012

5 il convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Convegno Società dei Concerti onlus 6 La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de Musique Romantique Française Venezia Musicalword.it CAMeC Centro Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Piazza Cesare Battisti 1 Comitato scientifico: Andrea Barizza, La Spezia Alexandre Dratwicki, Venezia Lorenzo Frassà, Lucca Roberto Illiano, Lucca / La Spezia Fulvia Morabito, Lucca Renato Ricco, Salerno Massimiliano Sala, Pistoia Renata Suchowiejko, Cracovia Convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Programma Lunedì 9 LUGLIO 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Roberto Illiano (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini / Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Francesco Masinelli (Presidente Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Cinzia Aloisini (Presidente Istituzione Servizi Culturali, Comune della Spezia) • Paola Sisti (Assessore alla Cultura, Provincia della Spezia) 10.30-11.30 Session 1 Nicolò Paganini e la scuola franco-belga presiede: Roberto Illiano 7 • Renato Ricco (Salerno): Virtuosismo e rivoluzione: Alexandre Boucher • Rohan H. Stewart-MacDonald (Leominster, UK): Approaches to the Orchestra in Paganini’s Violin Concertos • Danilo Prefumo (Milano): L’infuenza dei Concerti di Viotti, Rode e Kreutzer sui Con- certi per violino e orchestra di Nicolò Paganini -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Sarasate.Pdf

2 SEMBLANZAS DE COMPOSITORES ESPAÑOLES 29 PABLO DE SARASATE 1844 -1908 Robin Stowell Catedrático de Música de la Universidad de Cardiff ablo de Sarasate fue un heredero espiritual de Nicolò Paganini, un artista elegante y do- tado para el espectáculo cuya facilidad y arte innatos y cuya aristocrática presencia es- P cénica lo convirtieron posiblemente en el más grande y más venerado violinista y com- positor español. Según los testimonios contemporáneos, su elegante pero sutil estilo interpre- tativo era único y su desenfadado virtuosismo difería radicalmente tanto del enfoque “clásico” y enormemente intelectual de la “escuela” rival alemana de Joseph Joachim y sus discípulos co- mo de la técnica más rigurosa y el sonido enérgico y vibrante del más joven Eugène Ysaÿe. Así, Sir George Henschel llegó hasta el extremo de señalar que la interpretación de Sarasate del Concierto para violín Op. 64 de Mendelssohn en el Festival del Bajo Rin de 1877 “fue pa- ra los oídos alemanes como una suerte de revelación, provocando un auténtico furor”. Sarasate introdujo distinción, encanto y refinamiento en el arte de la ejecución violinística y presentaba su música con magnetismo, una facilidad y elegancia naturales y ningún tipo de afectación, hasta el punto de que su público encontraba irresistible su estilo “acariciante”. Su timbre solía describirse como dulce y puro, aunque no especialmente fuerte o vibrante, pero go- zó de un especial renombre por la precisión de su interpretación, la justeza de su afinación y, en palabras de Sir Alexander Mackenzie, su “talento para penetrar de forma intuitiva ‘debajo En «Semblanzas de compositores españoles» un especialista en musicología expone el perfil biográfico y artístico de un autor relevante en la historia de la música en España y analiza el contexto musical, social y cultural en el que desarrolló su obra. -

Program Notes by Dr

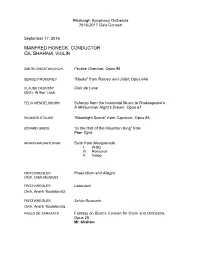

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. -

Program Notes

PROGRAM NOTES Camille Saint-Saëns – Introduction and Rondo capriccioso, Op. 28 Composition History Saint-Saëns composed this work in 1863. The date of the first performance is not known. The score calls for solo violin and an orchestra consisting of pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, and trumpets, with timpani and strings. Performance time is approximately nine minutes. Performance History The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Saint-Saëns’s Introduction and Rondo capriccioso were given at the Auditorium Theatre on December 13 and 14, 1895, with Martin Marsick as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on December 17, 18, 19, and 20, 1997, with Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg as soloist and Christoph Eschenbach conducting. The Orchestra first performed this work at the Ravinia Festival on July 7, 1956, with Zino Francescatti as soloist and Pierre Monteux conducting, and most recently on August 14, 1999, with Midori as soloist and Christoph Eschenbach conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Saint-Saëns’s Introduction and Rondo capriccioso in 1962 with Erick Friedman as soloist and Walter Hendl conducting for RCA. Camille Saint-Saëns Born October 9, 1835, Paris, France. Died December 16, 1921, Algiers, Algeria. Introduction and Rondo capriccioso, Op. 28 Like many composers who write concertos for instruments they do not play, Saint-Saëns welcomed the advice of the great Spanish violinist, Pablo de Sarasate, when he composed music for solo violin. They met when Sarasate was just fifteen, and Saint-Saëns twenty-four, and at the very beginning of a long and productive career. -

Sarasate Y Las Bellas Artes: La Iconografía Del Violinista

Sarasate y las Bellas Artes: la iconografía del violinista JOSÉ LUIS MOLINS MUGUETA* l 24 de septiembre de 2008 se me brindó la ocasión de pronunciar una E conferencia con el mismo título que encabeza este artículo, dentro del ci- clo organizado por la Sociedad de Estudios Históricos de Navarra, bajo la de- nominación de El mundo de Pablo Sarasate. Meses después, ya en 2009, revi- sado el texto y añadidas las pertinentes notas, se publicó como introducción y primera parte de la monografía Artistas en homenaje a Sarasate. Álbum de Roma 1882, de la que somos autores Ignacio J. Urricelqui y yo mismo. Al Ayuntamiento de Pamplona, entonces su editor por medio del Área de Cul- tura, agradezco la deferencia de permitir ahora esta “reimpresión”, que es co- mo sigue: INTRODUCCIÓN La conmemoración del centenario de la muerte de Pablo Sarasate, aca- ecida en su casa “Villa Navarra”, de Biarritz, el 20 de septiembre de 1908, viene ofreciendo diversas actividades promovidas en Navarra por adminis- traciones y entidades musicales o culturales. Singularmente el Ayunta- miento de Pamplona, por sí mismo o en colaboración con el Gobierno Fo- ral, ha querido conmemorar la efeméride del que fue Hijo Predilecto de la Ciudad. No han faltado los conciertos cultos o populares, los ciclos de con- ferencias, la cuidadosa restauración de alguno de los instrumentos de me- jor factura, la edición de monografías especializadas –alguna de próxima publicación– sobre la vida y obra musical, compuesta o adaptada por el cé- lebre violinista, junto a opúsculos divulgativos o de finalidad escolar y pe- dagógica. -

The Music of Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847-1935): a Critical Study

The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the written consent of the author and infomation derived from it should be acknowledged. The Music of Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847-1935): A Critical Study Duncan James Barker A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) Music Department University of Durham 1999 Volume 2 of 2 23 AUG 1999 Contents Volume 2 Appendix 1: Biographical Timeline 246 Appendix 2: The Mackenzie Family Tree 257 Appendix 3: A Catalogue of Works 260 by Alexander Campbell Mackenzie List of Manuscript Sources 396 Bibliography 399 Appendix 1: Biographical Timeline Appendix 1: Biographical Timeline NOTE: The following timeline, detailing the main biographical events of Mackenzie's life, has been constructed from the composer's autobiography, A Musician's Narrative, and various interviews published during his lifetime. It has been verified with reference to information found in The Musical Times and other similar sources. Although not fully comprehensive, the timeline should provide the reader with a useful chronological survey of Mackenzie's career as a musician and composer. ABBREVIATIONS: ACM Alexander Campbell Mackenzie MT The Musical Times RAM Royal Academy of Music 1847 Born 22 August, 22 Nelson Street, Edinburgh. 1856 ACM travels to London with his father and the orchestra of the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh, and visits the Crystal Palace and the Thames Tunnel. 1857 Alexander Mackenzie admits to ill health and plans for ACM's education (July). ACM and his father travel to Germany in August: Edinburgh to Hamburg (by boat), then to Hildesheim (by rail) and Schwarzburg-Sondershausen (by Schnellpost). -

Pablo De Sarasate’S Personal Style of Violin Playing and His Own Spanish-Styled Compositions

ABSTRACT Title of Document: SPANISH DANCES FOR VIOLIN: THEIR ORIGIN AND INFLUENCES Tao-Chang Yu, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2006 Directed By: Professor of Violin and Chair of the String Division, Gerald Fischbach, School of Music Many of the Spanish-styled violin virtuoso pieces from the mid-18th century to the twentieth century were dedicated to, or inspired by Pablo de Sarasate’s personal style of violin playing and his own Spanish-styled compositions. As both violinist and composer, Sarasate tailored these compositions to his technical flair and unique personality. Among Sarasate’s enormous output – total of sixty-one original compositions – the four volumes of Spanish Dances were the most popular and influential. Sarasate successfully translated many of his native folk dances and melodies in these dances, and introduced them to the European musical community with his amazing performances. In my written dissertation, I have discussed and illustrated in detail Sarasate’s four volumes of Spanish Dances, the origin of the Spanish-styled pieces, and the influenced works including Saint-Saëns’s Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, Op. 28, Édouard Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole, Op. 21, Kreisler’s transcriptions of Granados’ Spanish Dance in E minor and Albeníz’s Tango, and Waxman’s Carmen Fantasie. In the performance part of the dissertation, assisted by pianist Kuei-I Wu, I have played all of the mentioned works in their entirety, which is rare in modern concert programming. Through this project, I have gained deeper understanding of the Spanish -

“Pablo De Sarasate”

UNIVERSIDADE DE ÉVORA Departamento de Música “PABLO DE SARASATE” Elena Rodríguez Adame Orientador: Prof. Dr. Eduardo Lopes Co-orientador: Prof. Liviu Scripcaru Mestrado Música, Interpretaçao, 2011 Elena Rodríguez Adame -Pablo de Sarasate- UNIVERSIDADE DE ÉVORA Departamento de Música “PABLO DE SARASATE” Elena Rodríguez Adame Orientador: Prof. Dr. Eduardo Lopes Co-orientador: Prof. Liviu Scripcaru Mestrado Música, Interpretaçao, 2011 2 Elena Rodríguez Adame -Pablo de Sarasate- AGRADECIMIENTOS Me gustaría con estas palabras mostrar mi agradecimiento a todas las personas que me han ayudado a lo largo del proceso de elaboración de este trabajo. A mis orientadores, por su apoyo y sus consejos, y especialmente a Eduardo Lopes por el tiempo invertido en el proyecto y su gran ayuda, a pesar, muchas veces, de la distancia. Al personal de la Biblioteca Nacional de España, por su atención, su amabilidad y todo el asesoramiento que me han dado en la búsqueda de fuentes de información. Y por supuesto a Jesús, por ofrecerme su punto de vista siempre que lo requería, por su gran paciencia con los ordenadores y por su apoyo incondicional. ¡Muchas gracias! 3 Elena Rodríguez Adame -Pablo de Sarasate- ÍNDICE 1. INTRODUCCIÓN............................................................................................................9 2. HISTORIA DE UN PRODIGIO ...................................................................................10 2.1. Los años de infancia ..................................................................................................10 -

Ray Chen, Violin Julio Elizalde, Piano

�������������������������� ������� ������ ������������������������ ������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������������� ����������������� �������������� ������������������������������������������������ ������������������������ ���������������������������������������� �������� ���������������������������������������� ������������������������������������� ��������������������������� �������������������� �������������������������� ���������������� ������������������������������� ������������������������������� �����For tickets call toll-free ����������������1–888–CMA–0033 or online at ���������������������������clevelandart.org/performingarts Programs��������� are subject to change. ���������� ��������������� ������������� ����������� ������������� ������������� ������������������ �������������� ��������������� ����������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������� ������������������������������� ������������������������������� ������������������������� ������ ������������������������������������������������ ��������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� �������������������������������� �����������������������������������������������������������������Ray Chen, violin ��������������������������������������������������������������Julio Elizalde, piano ���������������������Wednesday, February 12, 2014 • 7:30������������������� p.m. Welcome������������������������� to the Cleveland ��������������Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland -

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONYORCHESTRA a JACOBS MASTERWORKS CONCERT Jahja Ling, Conductor

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONYORCHESTRA A JACOBS MASTERWORKS CONCERT Jahja Ling, conductor February 3, 2017 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS Violin Concerto No. 3 in B minor, Op. 61 Allegro non troppo Andantino quasi allegretto Molto moderato e maestoso – Allegro non troppo Benjamin Beilman, violin INTERMISSION PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. 4 in F minor, Op. 36 Andante sostenuto Andantino in modo di canzona Scherzo: Pizzicato ostinato Finale: Allegro con fuoco Festive Overture, Opus 96 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Born September 25, 1906, St. Petersburg Died August 9, 1975, Moscow Early in November 1954, the directors of the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow – who were planning a concert to celebrate the 37th anniversary of the Communist Revolution – suddenly realized that they needed a brief curtain-raiser for that concert. They turned to Shostakovich, who was a musical consultant for the Theatre, and asked him to write that piece. Faced with an immediate deadline, Shostakovich wrote as fast as he could, and his manuscript – the ink still wet – was taken by courier to the Theatre, where it was copied, rehearsed and premiered by the Bolshoi Theatre Orchestra under Alexander Melik-Pashayev on November 6, 1954. The music had not even existed a few days before. The directors wanted a piece to open a celebration concert, and that is exactly what they got. The overture springs to life on a series of ringing trumpet fanfares, and at the Presto it zips ahead on a saucy clarinet solo. Soon cellos and horns announce the overture’s main theme, a broad, open-spirited tune, and this develops with a great deal of energy.