The Violin Works of Joaquin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edouard Lalo Symphonie Espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Edouard Lalo Born January 27, 1823, Lille, France. Died April 22, 1892, Paris, France. Symphonie espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21 Lalo composed the Symphonie espagnole in 1874 for the violinist Pablo de Sarasate, who introduced the work in Paris on February 7, 1875. The score calls for solo violin and an orchestra consisting of two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, triangle, snare drum, harp, and strings. Performance time is approximately thirty-one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lalo's Symphonie espagnole were given at the Auditorium Theatre on April 20 and 21, 1900, with Leopold Kramer as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Bizet's Carmen is often thought to have ignited the French fascination with all things Spanish, but Edouard Lalo got there first. His Symphonie espagnole—a Spanish symphony that's really more of a concerto—was premiered in Paris by the virtuoso Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate the month before Carmen opened at the Opéra-Comique. And although Carmen wasn't an immediate success (Bizet, who died shortly after the premiere, didn't live to see it achieve great popularity), the Symphonie espagnole quickly became an international hit. It's still Lalo's best-known piece by a wide margin, just as Carmeneventually became Bizet's signature work. Although the surname Lalo is of Spanish origin, Lalo came by his French first name (not to mention his middle names, Victoire Antoine) naturally. His family had been settled in Flanders and in northern France since the sixteenth century. -

18.7 Instrumental 78S, Pp 173-195

78 rpm INSTRUMENTAL Sets do NOT have original albums unless indicated. If matrix numbers are needed for any of the items below in cases where they have been omitted, just let me know (preferably sooner rather than later). Albums require wider boxes than I use for records. If albums are available and are wanted, they will have to be shipped separately. U.S. postal charges for shipment within the U.S. are still reasonable (book rate) but out of country fees will probably be around $25.00 for an empty album. Capt. H. E. ADKINS dir. KNELLER HALL MUSICIANS 2107. 12” PW Plum HMV C.2445 [2B2922-IIA/2B2923-IIA]. FANFARES (Composed for the Musicians’ Benevolent Fund by Lord Berners, Sir. W. Davies, Dorothy Howell and Dame Edith Smyth). Two sides . Lt. rubs, cons . 2. $15.00. JOHN AMADIO [flutist] 2510. 12” Red Orth. Vla 9706 [Cc8936-II/Cc8937-II]. KONZERTSTÜCK, Op. 98: Finale (Heinrich Hofmann) / CONCERTINO, Op. 102 (Chaminade). Orch. dir. Lawrance Collingwood . Just about 1-2. $12.00. DANIELE AMFITHEATROF [composer, conductor] dir. PASDELOUP ORCH. 3311. 12” Green Italian Columbia GQX 10855, GQX 10866 [CPTX280-2/ CPTX281-2, CPTX282-3/ CPTX283- 1]. PANORAMA AMERICANO (Amfitheatrof). Four sides. Just about 1-2. $25.00. ENRIQUE FERDNANDEZ ARBOS [composer, conductor] dir. ORCH. 2222. 12” Blue Viva-Tonal Columbia 67607-D [WKX-62-2/WKX-63]. NOCHE DE ARABIA (Arbos). Two sides. Stkr. with Arbos’ autograph attached to lbl. side one. Just about 1-2. $20.00. LOUIS AUBERT [composer, con- ductor] dir. PARIS CONSERVA- TOIRE ORCH. 1570. 10” Purple Eng. -

Franco-Belgian Violin School: on the Rela- Tionship Between Violin Pedagogy and Compositional Practice Convegno Festival Paganiniano Di Carro 2012

5 il convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Convegno Società dei Concerti onlus 6 La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de Musique Romantique Française Venezia Musicalword.it CAMeC Centro Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Piazza Cesare Battisti 1 Comitato scientifico: Andrea Barizza, La Spezia Alexandre Dratwicki, Venezia Lorenzo Frassà, Lucca Roberto Illiano, Lucca / La Spezia Fulvia Morabito, Lucca Renato Ricco, Salerno Massimiliano Sala, Pistoia Renata Suchowiejko, Cracovia Convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Programma Lunedì 9 LUGLIO 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Roberto Illiano (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini / Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Francesco Masinelli (Presidente Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Cinzia Aloisini (Presidente Istituzione Servizi Culturali, Comune della Spezia) • Paola Sisti (Assessore alla Cultura, Provincia della Spezia) 10.30-11.30 Session 1 Nicolò Paganini e la scuola franco-belga presiede: Roberto Illiano 7 • Renato Ricco (Salerno): Virtuosismo e rivoluzione: Alexandre Boucher • Rohan H. Stewart-MacDonald (Leominster, UK): Approaches to the Orchestra in Paganini’s Violin Concertos • Danilo Prefumo (Milano): L’infuenza dei Concerti di Viotti, Rode e Kreutzer sui Con- certi per violino e orchestra di Nicolò Paganini -

¿Granados No Es Un Gran Maestro? Análisis Del Discurso Historiográfico Sobre El Compositor Y El Canon Nacionalista Español

¿Granados no es un gran maestro? Análisis del discurso historiográfico sobre el compositor y el canon nacionalista español MIRIAM PERANDONES Universidad de Oviedo Resumen Enrique Granados (1867-1916) es uno de los tres compositores que conforman el canon del Nacionalismo español junto a Manuel de Falla (1876- 1946) e Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909) y, sin embargo, este músico suele quedar a la sombra de sus compatriotas en los discursos históricos. Además, Granados también está fuera del “trío fundacional” del Nacionalismo formado por Felip Pedrell (1841-1922) —considerado el maestro de los tres compositores nacionalistas, y, en consecuencia, el “padre” del nacionalismo español—Albéniz y Falla. En consecuencia, uno de los objetivos de este trabajo es discernir por qué Granados aparece en un lugar secundario en la historiografía española, y cómo y en base a qué premisas se conformó este canon musical. Palabras clave: Enrique Granados, canon, Nacionalismo, historiografia musical. Abstract Enrique Granados (1867-1916) is one of the three composers Who comprise the canon of Spanish nationalism, along With Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) and Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909). HoWeVer, in the realm of historical discourse, Granados has remained in the shadoW of his compatriots. MoreoVer, Granados lies outside the “foundational trio” of nationalism, formed by Felip Pedrell (1841-1922)— considered the teacher of the three nationalist composer and, as a consequence, the “father” of Spanish nationalism—Albéniz y Falla. Therefore, one of the objectiVes of this study is to discern why Granados occupies a secondary position in Spanish historiography, and most importantly, for What reasons the musical canon eVolVed as it did. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

An Investigation of the Sonata-Form Movements for Piano by Joaquín Turina (1882-1949)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository CONTEXT AND ANALYSIS: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE SONATA-FORM MOVEMENTS FOR PIANO BY JOAQUÍN TURINA (1882-1949) by MARTIN SCOTT SANDERS-HEWETT A dissertatioN submitted to The UNiversity of BirmiNgham for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC DepartmeNt of Music College of Arts aNd Law The UNiversity of BirmiNgham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Composed between 1909 and 1946, Joaquín Turina’s five piano sonatas, Sonata romántica, Op. 3, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Op. 24, Sonata Fantasía, Op. 59, Concierto sin Orquesta, Op. 88 and Rincón mágico, Op. 97, combiNe established formal structures with folk-iNspired themes and elemeNts of FreNch ImpressioNism; each work incorporates a sonata-form movemeNt. TuriNa’s compositioNal techNique was iNspired by his traiNiNg iN Paris uNder ViNceNt d’Indy. The unifying effect of cyclic form, advocated by d’Indy, permeates his piano soNatas, but, combiNed with a typically NoN-developmeNtal approach to musical syNtax, also produces a mosaic-like effect iN the musical flow. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Sarasate.Pdf

2 SEMBLANZAS DE COMPOSITORES ESPAÑOLES 29 PABLO DE SARASATE 1844 -1908 Robin Stowell Catedrático de Música de la Universidad de Cardiff ablo de Sarasate fue un heredero espiritual de Nicolò Paganini, un artista elegante y do- tado para el espectáculo cuya facilidad y arte innatos y cuya aristocrática presencia es- P cénica lo convirtieron posiblemente en el más grande y más venerado violinista y com- positor español. Según los testimonios contemporáneos, su elegante pero sutil estilo interpre- tativo era único y su desenfadado virtuosismo difería radicalmente tanto del enfoque “clásico” y enormemente intelectual de la “escuela” rival alemana de Joseph Joachim y sus discípulos co- mo de la técnica más rigurosa y el sonido enérgico y vibrante del más joven Eugène Ysaÿe. Así, Sir George Henschel llegó hasta el extremo de señalar que la interpretación de Sarasate del Concierto para violín Op. 64 de Mendelssohn en el Festival del Bajo Rin de 1877 “fue pa- ra los oídos alemanes como una suerte de revelación, provocando un auténtico furor”. Sarasate introdujo distinción, encanto y refinamiento en el arte de la ejecución violinística y presentaba su música con magnetismo, una facilidad y elegancia naturales y ningún tipo de afectación, hasta el punto de que su público encontraba irresistible su estilo “acariciante”. Su timbre solía describirse como dulce y puro, aunque no especialmente fuerte o vibrante, pero go- zó de un especial renombre por la precisión de su interpretación, la justeza de su afinación y, en palabras de Sir Alexander Mackenzie, su “talento para penetrar de forma intuitiva ‘debajo En «Semblanzas de compositores españoles» un especialista en musicología expone el perfil biográfico y artístico de un autor relevante en la historia de la música en España y analiza el contexto musical, social y cultural en el que desarrolló su obra. -

Les Six and Their Music an Incidental Partnership

Berklee College of Music Les Six and Their Music An Incidental Partnership Luís F. Gomes Zanforlin History of Music in the European Tradition MHIS-P203-006 Dennis Leclaire Mar/09/2017 1 Les Six is an group of six French composers who performed and published under the same name. In post WWI France the six composers whom shared an appreciation for the music of Satie and the ideas of Cocteau gathered weekly at a local pub where they entertained themselves and enjoyed the company of many influentials and artists of the avant-guard Paris. After a joined performance at the Lyre Pallette on April fifth in 1919 and a news paper publication by Henri Collet comparing the six composers to the Russian Five, they became known as “Les Six”. The composers have distinct musical style partook in creating a new French music style free from the influence of German music. Although their partnership was informally forged by the influence of Cocteau the composers took advantage of it publishing piano books and performing concerts featuring the six composers. Georges Auric (1899-1983) was one of the founders of the group together with Durey and Honegger. The aesthetic of his music is contemporary to Pulenc and often resources to repetition and motion inducing rhythms, similar to 1920’s the futurism style. Auric composed a large number of film scores for Avant Guard films. Works: “Prélude” (1919, piano piece); “Le 14 Juillet” (1921, overture from Maniés de la Tour Eiffel); “Les Matelots” (1924, dance music for orchestra); “Cinq Bagatelles” (1925, four hands piano piece); “La Belle et Avenant” (1946, film score for La Belle et La Bête); “Where is your heart” (1952, film score for Moulin Rouge). -

Program Notes by Dr

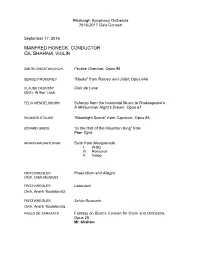

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. -

Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes Vivian Buchanan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 6-4-2018 Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes Vivian Buchanan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Buchanan, Vivian, "Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4744. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4744 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVOLVING PERFORMANCE PRACTICE OF DEBUSSY’S PIANO PRELUDES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in The Department of Music and Dramatic Arts by Vivian Buchanan B.M., New England Conservatory of Music, 2016 August 2018 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………..iii Chapter 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………… 1 2. The Welte-Mignon…………………………………………………………. 7 3. The French Harpsichord Tradition………………………………………….18 4. Debussy’s Piano Rolls……………………………………………………....35 5. The Early Debussystes……………………………………………………...52 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………...63 Selected Discography………………………………………………………………..66 Vita…………………………………………………………………………………..67 ii Abstract Between 1910 and 1912 Claude Debussy recorded twelve of his solo piano works for the player piano company Welte-Mignon. Although Debussy frequently instructed his students to play his music exactly as written, his own recordings are rife with artistic liberties and interpretive freedom. -

An Introduction to Joaquin Nin (1879-1949) and His "Veinte Cantos Populares Espanoles"

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 An Introduction to Joaquin Nin (1879-1949) and His "Veinte Cantos Populares Espanoles". Gina Lottinger Anthon Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Anthon, Gina Lottinger, "An Introduction to Joaquin Nin (1879-1949) and His "Veinte Cantos Populares Espanoles"." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6930. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6930 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.