Pablo De Sarasate’S Personal Style of Violin Playing and His Own Spanish-Styled Compositions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edouard Lalo Symphonie Espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Edouard Lalo Born January 27, 1823, Lille, France. Died April 22, 1892, Paris, France. Symphonie espagnole for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 21 Lalo composed the Symphonie espagnole in 1874 for the violinist Pablo de Sarasate, who introduced the work in Paris on February 7, 1875. The score calls for solo violin and an orchestra consisting of two flutes and piccolo, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, timpani, triangle, snare drum, harp, and strings. Performance time is approximately thirty-one minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lalo's Symphonie espagnole were given at the Auditorium Theatre on April 20 and 21, 1900, with Leopold Kramer as soloist and Theodore Thomas conducting. Bizet's Carmen is often thought to have ignited the French fascination with all things Spanish, but Edouard Lalo got there first. His Symphonie espagnole—a Spanish symphony that's really more of a concerto—was premiered in Paris by the virtuoso Spanish violinist Pablo de Sarasate the month before Carmen opened at the Opéra-Comique. And although Carmen wasn't an immediate success (Bizet, who died shortly after the premiere, didn't live to see it achieve great popularity), the Symphonie espagnole quickly became an international hit. It's still Lalo's best-known piece by a wide margin, just as Carmeneventually became Bizet's signature work. Although the surname Lalo is of Spanish origin, Lalo came by his French first name (not to mention his middle names, Victoire Antoine) naturally. His family had been settled in Flanders and in northern France since the sixteenth century. -

The Application of Contemporary Double Bass Left Hand Techniques Applied in the Orchestra Repertoire

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2014 The Application of Contemporary Double Bass Left Hand Techniques Applied in the Orchestra Repertoire Eric Hilgenstieler University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Music Education Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Hilgenstieler, Eric, "The Application of Contemporary Double Bass Left Hand Techniques Applied in the Orchestra Repertoire" (2014). Dissertations. 269. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/269 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi THE APPLICATION OF CONTEMPORARY DOUBLE BASS LEFT HAND TECHNIQUES APPLIED IN THE ORCHESTRA REPERTOIRE by Eric Hilgenstieler Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts May 2014 ABSTRACT THE APLICATION OF CONTEMPORARY DOUBLE BASS LEFT-HAND TECHNIQUES APPLIED IN THE ORCHESTRA REPERTOIRE by Eric Hilgenstieler May 2014 The uses of contemporary left hand techniques are related to solo playing in many ways. In fact, most of these techniques were arguably developed for this kind of repertoire. Generally the original solo repertoire is idiomatic for the double bass. The same cannot be said for the orchestral repertoire, which presents many technical problems too difficult to solve using the traditional technique. -

Franco-Belgian Violin School: on the Rela- Tionship Between Violin Pedagogy and Compositional Practice Convegno Festival Paganiniano Di Carro 2012

5 il convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Convegno Società dei Concerti onlus 6 La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de Musique Romantique Française Venezia Musicalword.it CAMeC Centro Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Piazza Cesare Battisti 1 Comitato scientifico: Andrea Barizza, La Spezia Alexandre Dratwicki, Venezia Lorenzo Frassà, Lucca Roberto Illiano, Lucca / La Spezia Fulvia Morabito, Lucca Renato Ricco, Salerno Massimiliano Sala, Pistoia Renata Suchowiejko, Cracovia Convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Programma Lunedì 9 LUGLIO 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Roberto Illiano (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini / Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Francesco Masinelli (Presidente Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Cinzia Aloisini (Presidente Istituzione Servizi Culturali, Comune della Spezia) • Paola Sisti (Assessore alla Cultura, Provincia della Spezia) 10.30-11.30 Session 1 Nicolò Paganini e la scuola franco-belga presiede: Roberto Illiano 7 • Renato Ricco (Salerno): Virtuosismo e rivoluzione: Alexandre Boucher • Rohan H. Stewart-MacDonald (Leominster, UK): Approaches to the Orchestra in Paganini’s Violin Concertos • Danilo Prefumo (Milano): L’infuenza dei Concerti di Viotti, Rode e Kreutzer sui Con- certi per violino e orchestra di Nicolò Paganini -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Rep List 1.Pub

Richmond Symphony Orchestra League Student Concerto Competition Repertoire Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Guitar & percussion students are welcome to participate; Please contact Anne Hoffler, contest coordinator, at aahoffl[email protected] for repertoire approval no later than November 30. VIOLIN Faure Elegy, Op. 24 Bach All Violin concerti Haydn Cello Concerto No. 1 in C major Beethoven Violin Concerto in D major Haydn Cello Concerto No. 2 in D major Beethoven Romance No. 1 in G major Lalo Cello Concerto in D minor Beethoven Romance No. 2 in F major Rubinstein Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op.96 Bériot Scéne de Ballet, Op. 100 Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op.33 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 7 in G major Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op. 119 Bériot Violin Concerto No. 9 in A minor Schumann Cello Concerto in A minor Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor Shostakovich Concerto for Cello No. 1 Haydn All Violin concerti Stamitz All Cello concerti Kabalevsky Violin Concerto in C Major, Op. 48 R. Strauss Romanze in F major Lalo Symphonie Espagnole Tchaikovsky Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op.33 Massenet Méditation from Thaïs Vivaldi All Cello concerti Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op.64 Mozart Violin Concerto No. 1 in B-flat major BASS Mozart Violin Concerto No. 2 in D major Bottesini Double Bass Concerto No.2 in B minor Mozart Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major Capuzzi Double Bass Concerto in D major Mozart Violin Concerto No. -

Sarasate.Pdf

2 SEMBLANZAS DE COMPOSITORES ESPAÑOLES 29 PABLO DE SARASATE 1844 -1908 Robin Stowell Catedrático de Música de la Universidad de Cardiff ablo de Sarasate fue un heredero espiritual de Nicolò Paganini, un artista elegante y do- tado para el espectáculo cuya facilidad y arte innatos y cuya aristocrática presencia es- P cénica lo convirtieron posiblemente en el más grande y más venerado violinista y com- positor español. Según los testimonios contemporáneos, su elegante pero sutil estilo interpre- tativo era único y su desenfadado virtuosismo difería radicalmente tanto del enfoque “clásico” y enormemente intelectual de la “escuela” rival alemana de Joseph Joachim y sus discípulos co- mo de la técnica más rigurosa y el sonido enérgico y vibrante del más joven Eugène Ysaÿe. Así, Sir George Henschel llegó hasta el extremo de señalar que la interpretación de Sarasate del Concierto para violín Op. 64 de Mendelssohn en el Festival del Bajo Rin de 1877 “fue pa- ra los oídos alemanes como una suerte de revelación, provocando un auténtico furor”. Sarasate introdujo distinción, encanto y refinamiento en el arte de la ejecución violinística y presentaba su música con magnetismo, una facilidad y elegancia naturales y ningún tipo de afectación, hasta el punto de que su público encontraba irresistible su estilo “acariciante”. Su timbre solía describirse como dulce y puro, aunque no especialmente fuerte o vibrante, pero go- zó de un especial renombre por la precisión de su interpretación, la justeza de su afinación y, en palabras de Sir Alexander Mackenzie, su “talento para penetrar de forma intuitiva ‘debajo En «Semblanzas de compositores españoles» un especialista en musicología expone el perfil biográfico y artístico de un autor relevante en la historia de la música en España y analiza el contexto musical, social y cultural en el que desarrolló su obra. -

Carmen Fantasie Brillante Sheet Music

Carmen Fantasie Brillante Sheet Music Download carmen fantasie brillante sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of carmen fantasie brillante sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 4588 times and last read at 2021-09-23 12:20:09. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of carmen fantasie brillante you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Ensemble: Concert Band Level: Intermediate [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Fantaisie Brillante Sur Des Thmes De Carmen For Alto Saxophone And Concert Band Percussion 2 Part Fantaisie Brillante Sur Des Thmes De Carmen For Alto Saxophone And Concert Band Percussion 2 Part sheet music has been read 3510 times. Fantaisie brillante sur des thmes de carmen for alto saxophone and concert band percussion 2 part arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 11:25:19. [ Read More ] Fantaisie Brillante Sur Des Thmes De Carmen For Alto Saxophone And Concert Band Bb Trumpet 1 Part Fantaisie Brillante Sur Des Thmes De Carmen For Alto Saxophone And Concert Band Bb Trumpet 1 Part sheet music has been read 3477 times. Fantaisie brillante sur des thmes de carmen for alto saxophone and concert band bb trumpet 1 part arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 3 preview and last read at 2021-09-23 16:14:29. [ Read More ] Fantaisie Brillante Sur Des Thmes De Carmen For Alto Saxophone And Concert Band Bassoon 2 Partt Fantaisie Brillante Sur Des Thmes De Carmen For Alto Saxophone And Concert Band Bassoon 2 Partt sheet music has been read 3224 times. -

Program Notes by Dr

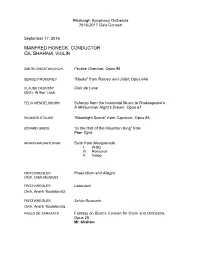

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. -

Carmen Fantasy Sheet Music

Carmen Fantasy Sheet Music Download carmen fantasy sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 6 pages partial preview of carmen fantasy sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 7063 times and last read at 2021-09-27 16:08:14. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of carmen fantasy you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Ensemble: Woodwind Quintet Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Carmen Fantasy For Flute And Band Carmen Fantasy For Flute And Band sheet music has been read 3103 times. Carmen fantasy for flute and band arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 06:16:39. [ Read More ] Carmen Fantasy For Duet 2 Violins Carmen Fantasy For Duet 2 Violins sheet music has been read 10055 times. Carmen fantasy for duet 2 violins arrangement is for Early Intermediate level. The music notes has 5 preview and last read at 2021-09-27 09:22:47. [ Read More ] Carmen Concert Fantasy Habanera Carmen Concert Fantasy Habanera sheet music has been read 2619 times. Carmen concert fantasy habanera arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 04:16:13. [ Read More ] Habanera From Carmen Concert Fantasy Op 25 Arranged For Piano Trio Habanera From Carmen Concert Fantasy Op 25 Arranged For Piano Trio sheet music has been read 8229 times. Habanera from carmen concert fantasy op 25 arranged for piano trio arrangement is for Advanced level. -

2019-2020 Philharmonia No. 3

Lynn Philharmonia No. 3 Featuring the winners of the 2019 Lynn Concerto Competition. Saturday, Nov. 9, 2019 Sunday, Nov. 10, 2019 2019-2020 Season Lynn Philharmonia Roster VIOLIN CELLO FRENCH HORN Carlos Avendano Georgiy Khokhlov Chase DeCarlo Alexander Babin Devin LaMarr Alexander Hofmann Zulfiya Bashirova Michael Puryear Ting-An Lee David Brill Clarissa Viera Sarah Rodnick Kayla Bryan Davron Ziyodjonov Christa Rotolo Mingyue Fei Daniel Guevara DOUBLE BASS TRUMPET Benjamin Kremer Luis Gutierrez Diana Lopez Ricardo Lemus Austin King Oscar Mason Shiyu Liu Peter Savage Abigail Rowland Jenna Mangum Benjamin Shaposhnikov Gerson Medina FLUTE Karla Mejias Naomi Franklin TROMBONE David Mersereau Seung Jeon Aaron Chan Moises Molina Scott Quirk Tyler Coffman Nalin Myoung Lydia Roth Mario Rivieccio Sol Ochoa Castro Aaron Small Sebastian Orellana OBOE Francesca Puro Garrett Arosemena Ott Melanie Riordan Jin Cai PERCUSSION Askar Salimdjanov Amy Han Seth Burkhart Mengyu Shen Kari Jenks Justin Ochoa Shuyi Wang Blaise Rothwell Jonathon Winter CLARINET Miranda Smith Yu Xie Dunia Andreu Benitez Mario Zelaya Kelsey Castellanos HARP Taylor Overholt Yana Lyashko VIOLA Abby Dreher BASSOON Ellen Galentas Fabiola Hoyo Gabriel Galley Dennis Pearson Hyemin Lee Meng-Hsin Shih Marina Monclova Lopez Guillermo Yalanda Daniel Moore Vishnu Ramankutty Mario Rivera Jovani Williams Thomas Wong Lynn Philharmonia No. 3 Guillermo Figueroa, music director and conductor Saturday, Nov. 9 – 7:30 p.m. Sunday, Nov. 10 – 4 p.m. Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center On October 4, 5 and 6, thirty-seven students performed before guest judges Sarah Johnson, violin (Converse College), David Jackson, trombone (University of Michigan), and Baruch Meir, piano (Arizona State University & President of the Bosendorfer/Yamaha USASU International Piano Competition). -

The Wonicaeducator

THEWONICAEDUCATOR @2006 EXPANDS PROWDES T.H.E KNOWLEDGE OF IN-DEPTH INFORMATION HARMONICA ON A WIDE RANGE OF TEACHING AND MUSICAL AND IIARMONICA PL.4YING REL/ITED TOPICS Volume 13 lssue 2 Internatìonal Publication Dedìcated to the Advancemenf of Harmonica Education Summer 2006 Sincethe 1980s,Nick Dallett has been active in the acousticmusic scenein the Pacific Northwest, and has composedand performed a wide Interpretation: Finding Your Style I variely of music, from conlemporaty classical chamber music to hard rock. In addition to creating music, Nick has been active since 1990 in The Construction of Diatonic and Echo 8 Pipe Harmonicas promoting regional musicians of the Pacific l'{orthwest. This has been "A Using PayPal for Subscriptions,Pur- t0 through his radio progranx Portable Stage" on KSER (90.7, Everett, chasingHarmonica Books, and Ads Washington),through his record label, BAF, through his work in cata- loguing the Folklife Festival tape archives, and through the Olympic AcousticGuitar Association,an organization he co-foundedin 1991. From The Editor "The Traditional Irish Music and the Nick Dallett wroÍe a book called, Musical Experience,"which is Diatonic Harmonica published by Acoustic Confusion Music (@ 1991 Nick Dallett/Acoustic Beginning and Intermediate Level ConfusionMusic). Mr. Dallett has given his kind permission to reprint Harmonica Players sorne articles his book. The follou,ing reprint is called Beginning & Intermediate Level Bass "Interpretation: from Finding Your Style." Many of the ideas in this article will Harmonica Players be of valueto harntonicasoloists and ensembleplayers. Beginning,Intermediate, and Advanced level Chromatic and Bass Interpretation: Finding Your Style Harmonica Players (Reprintedfrom the Winter 1997 Issue) Scales,Intervals, Rhythms, Arpeggios, and Exercises for Chromatic and BassHarmonicas By Nick Dallett (Reprintedwith permissionof AcousticConfusion Music) Duets, Trios, and Quartets for Harmonica Ensembles EXERCISE - Comparing The 48-Chord Harmonica I) Find two recordingsof a classicalcomposition. -

City Research Online

Askin, C. (1996). Early Recorded Violinists. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) City Research Online Original citation: Askin, C. (1996). Early Recorded Violinists. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) Permanent City Research Online URL: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/7937/ Copyright & reuse City University London has developed City Research Online so that its users may access the research outputs of City University London's staff. Copyright © and Moral Rights for this paper are retained by the individual author(s) and/ or other copyright holders. All material in City Research Online is checked for eligibility for copyright before being made available in the live archive. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to from other web pages. Versions of research The version in City Research Online may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check the Permanent City Research Online URL above for the status of the paper. Enquiries If you have any enquiries about any aspect of City Research Online, or if you wish to make contact with the author(s) of this paper, please email the team at [email protected]. EARLY RECORDED VIOLINISTS CIHAT AS KIN 1996 EARLY RECORDED VIOLINISTS Cihat Askin Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Musical Arts City University Music Department April 1996 2 CONTENTS Acknowledgements 25 Abstract 26 Preface 27 Introduction 29 Abbreviations & Symbols 32 1. Joseph Joachim 33 1.1 A Short Biography 34 1.2 Joachim: Beethoven and Brahms Concertos 35 1.3 Joachim as Performer 39 1.4 Joachim as Teacher 40 1.5 Analysis of Joachim's Recordings 43 1.5.1 Bach Adagio and Tempo di Borea 44 1.5.2 Vibrato 60 1.5.3 Chords 61 1.5.4 Perfect Rubato 62 1.5.5 Agogic Accents 62 1.5.6 Intonation 63 1.6 Conclusion 66 2.