Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

Various Total Recall Volume 10 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Total Recall Volume 10 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Total Recall Volume 10 Country: US Released: 1998 Style: Roots Reggae MP3 version RAR size: 1862 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1995 mb WMA version RAR size: 1427 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 540 Other Formats: DMF AU MMF APE MP2 DTS AC3 Tracklist 1 –Carlton Patterson Hypocrite 2 –Barrington Levy Warm And Sunny Day 3 –Sugar Minott Mr. DC 4 –Hugh Brown* Mr. Music Man 5 –Carlton Patterson On Bending Knees 6 –Johnny Ringo One Time Ringo 7 –Ray I Weather Man Skank 8 –Dillinger Dip Them Bedward 9 –Michael Scotland Love Is A Treasure 10 –General Echo Track Shoes 11 –Larry Marshall I Admire You 12 –Sugar Minott All Kind A People 13 –I Roy* Can't Wine 14 –Stanley Beckford Country Gal Credits Accompanied By – The Soul Syndicate Arranged By – Aaron Patterson, Carlton Patterson, Judith Patterson, King Tubby, Philip Smart Bass – Lloyd Parks, Robbie* Compiled By – Carlton Patterson, Judith Patterson, Vincent Edwards Drums – Sly* Engineer – Carlton Patterson, Errol T*, King Tubby, Michael Campbell, Philip Smart, Scientist Horns – Deadly Headly*, Bobby Ellis, Tommy McCook Producer – Carlton Patterson Notes Recorded at Channel One, Randys' & King Tubby's in Kingston Jamaica W.I. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 054645150828 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year VPRL-1508 Various Total Recall Volume 10 (LP, Comp) VP Records VPRL-1508 US 1998 VPCT 1508 Various Total Recall Volume 10 (Cass, Comp) VP Records VPCT 1508 US 1998 Related -

Basslines 2: Everything Can Be Dub Has No End?

Basslines 2: Everything Can Be Dub Has No End? Column in the zweikommasieben Magazin #11, 2015 (www.zweikommasieben.ch ) Annotated version with sound and text references Text: Marius ‚Comfortnoise‘ Neukom (www.comfortnoise.com ) „Everything can be dub” says Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry in the documentary Dub Echoes .1 He is not too far off with that comment because dub is actually more of a production technology that can apply to all styles than it is a genre of music. However, it is cer- tainly worth looking at dub more intimately. In his professorial dissertation Dub. Soundscapes & Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae , Michael E. Veal (2007) fo- cuses on musical developments in Kingston, Jamaica between 1968 and 1985 and presents impressive analyses that involve musicological, psychoacoustic and cultural theory aspects.2 For Veal, dub is a sub-style of roots reggae which has been dismantled by predomi- nantly electronic sound processing and converted into new, often unfinished sound 1 Natal, 2009, 25:32. 2 See the blog entry „The Essential, Annotated Dub Library“ for further recommendable literature and movies in the context of Dub and Reggae: www.comfortnoise.com/blog/2015/06/essential-dub- library.html version 2015-07-19 structures. Its musical effect and technical aspects have transformed pop music and enabled genres such as hip-hop and techno to be born. Veal provides detailed analyses that document the difference between the original pieces and their „dub versions” as well as indicate the individual touches of leading engineers like King -

The Dub June 2018

1 Spanners & Field Frequency Sound System, Reading Dub Club 12.5.18 2 Editorial Dub Front cover – Indigenous Resistance: Ethiopia Dub Journey II Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 25 for the month of Levi. This is our 3rd anniversary issue, Natty Mark founding the magazine in June 2016, launching it at the 1st Mikey Dread Festival near Witney (an event that is also 3 years old this year). This summer sees a major upsurge in events involving members of The Dub family – Natty HiFi, Jah Lambs & Lions, Makepeace Promotions, Zion Roots, Swindon Dub Club, Field Frequency Sound System, High Grade and more – hence the launch of the new Dub Diary Newsletter at sessions. The aim is to spread the word about forthcoming gigs and sessions across the region, pulling different promoters’ efforts together. Give thanks to the photographers who have allowed us to use their pictures of events this month. We welcome some new writers this month too – thanks you for stepping up Benjamin Ital and Eric Denham (whose West Indian Music Appreciation Society newsletter ran from 1966 to 1974 and then from 2014 onwards). Steve Mosco presents a major interview with U Brown from when they recorded an album together a few years ago. There is also an interview with Protoje, a conversation with Jah9 from April’s Reggae Innovations Conference, a feature on the Indigenous Resistance collective, and a feature on Augustus Pablo. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors. -

Interview with Donovan Germain 25 Years Penthouse Records

Interview with Donovan Germain 25 Years Penthouse Records 02/19/2014 by Angus Taylor Jamaican super-producer Donovan Germain recently celebrated 25 years of his Penthouse label with the two-disc compilation Penthouse 25 on VP Records. But Germain’s contribution to reggae and dancehall actually spans closer to four decades since his beginnings at a record shop in New York. The word “Germane” means relevant or pertinent – something Donovan has tried to remain through his whole career - and certainly every reply in this discussion with Angus Taylor was on point. He was particularly on the money about the Reggae Grammy, saying what has long needed to be said when perennial complaining about the Grammy has become as comfortable and predictable as the awards themselves. How did you come to migrate to the USA in early 70s? My mother migrated earlier and I came and joined her in the States. I guess in the sixties it was for economic reasons. There weren’t as many jobs in Jamaica as there are today so people migrated to greener pastures. I had no choice. I was a foolish child, my mum wanted me to come so I had to come! What was New York like for reggae then? Very little reggae was being played in New York. Truth be told Ken Williams was a person who was very instrumental in the outbreak of the music in New York. Certain radio stations would play the music in the grave yard hours of the night. You could hear the music at half past one, two o’clock. -

Dennis Brown ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The

DATE March 27, 2003 e TO Vartan/Um Creative Services/Meire Murakami FROM Beth Stempel EXTENSION 5-6323 SUBJECT Dennis Brown COPIES Alice Bestler; Althea Ffrench; Amy Gardner; Andy McKaie; Andy Street; Anthony Hayes; Barry Korkin; Bill Levenson; Bob Croucher; Brian Alley; Bridgette Marasigan; Bruce Resnikoff; Calvin Smith; Carol Hendricks; Caroline Fisher; Cecilia Lopez; Charlie Katz; Cliff Feiman; Dana Licata; Dana Smart; Dawn Reynolds; [email protected]; Elliot Kendall; Elyssa Perez; Frank Dattoma; Frank Perez; Fumiko Wakabayashi; Giancarlo Sciama; Guillevermo Vega; Harry Weinger; Helena Riordan; Jane Komarov; Jason Pastori; Jeffrey Glixman; Jerry Stine; Jessica Connor; Jim Dobbe; JoAnn Frederick; Joe Black; John Gruhler; Jyl Forgey; Karen Sherlock; Kelly Martinez; Kerri Sullivan; Kim Henck; Kristen Burke; Laura Weigand; Lee Lodyga; Leonard Kunicki; Lori Froeling; Lorie Slater; Maggie Agard; Marcie Turner; Margaret Goldfarb; Mark Glithero; Mark Loewinger; Martin Wada; Melanie Crowe; Michael Kachko; Michelle Debique; Nancy Jangaard; Norma Wilder; Olly Lester; Patte Medina; Paul Reidy; Pete Hill; Ramon Galbert; Randy Williams; Robin Kirby; Ryan Gamsby; Ryan Null; Sarah Norris; Scott Ravine; Shelin Wing; Silvia Montello; Simon Edwards; Stacy Darrow; Stan Roche; Steve Heldt; Sujata Murthy; Todd Douglas; Todd Nakamine; Tracey Hoskin; Wendy Bolger; Wendy Tinder; Werner Wiens ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The Complete A&M Years CD #: B0000348-02 UPC #: 6 069 493 683-2 CD Logo: A&M Records & Chronicles Attached please find all necessary liner notes and credits for this package. Beth Dennis Brown – Complete A&M Years B0000348-02 1 12/01/19 11:49 AM Dennis Brown The Complete A&M Years (CD Booklet) Original liner notes from The Prophet Rides Again This album is dedicated to the Prophet Gad (Dr. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

The Funky Diaspora

The Funky Diaspora: The Diffusion of Soul and Funk Music across The Caribbean and Latin America Thomas Fawcett XXVII Annual ILLASA Student Conference Feb. 1-3, 2007 Introduction In 1972, a British band made up of nine West Indian immigrants recorded a funk song infused with Caribbean percussion called “The Message.” The band was Cymande, whose members were born in Jamaica, Guyana, and St. Vincent before moving to England between 1958 and 1970.1 In 1973, a year after Cymande recorded “The Message,” the song was reworked by a Panamanian funk band called Los Fabulosos Festivales. The Festivales titled their fuzzed-out, guitar-heavy version “El Mensaje.” A year later the song was covered again, this time slowed down to a crawl and set to a reggae beat and performed by Jamaican singer Tinga Stewart. This example places soul and funk music in a global context and shows that songs were remade, reworked and reinvented across the African diaspora. It also raises issues of migration, language and the power of music to connect distinct communities of the African diaspora. Soul and funk music of the 1960s and 1970s is widely seen as belonging strictly in a U.S. context. This paper will argue that soul and funk music was actually a transnational and multilingual phenomenon that disseminated across Latin America, the Caribbean and beyond. Soul and funk was copied and reinvented in a wide array of Latin American and Caribbean countries including Brazil, Panama, Jamaica, Belize, Peru and the Bahamas. This paper will focus on the music of the U.S., Brazil, Panama and Jamaica while highlighting the political consciousness of soul and funk music. -

Various Let There Be Version, Rupie Edwards & Friends Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Let There Be Version, Rupie Edwards & Friends mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Let There Be Version, Rupie Edwards & Friends Country: UK Released: 1990 Style: Roots Reggae, Dub, Rocksteady MP3 version RAR size: 1668 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1377 mb WMA version RAR size: 1298 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 963 Other Formats: AIFF AC3 AUD AAC MP3 MPC FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits My Conversation A1 –Slim Smith And The Uniques Written-By – K. Smith* 100,000 Dollars A2 –The Success All Stars Written-By – Rupie Edwards Doctor Come Quick A3 –Hugh Roy Junior* Written-By – Hugh Roy Jnr.* Half Way Tree Pressure A4 –Shorty The President Written By – D. Thompson Mi Nuh Matta A5 –El Cisco Delgado Written-By – Delgado* Tribute To Slim Smith A6 –Tyrone Downie Written-By – Downie* Doctor Satan Echo Chamber A7 –The Success All Stars Written-By – Rupie Edwards Yamaha Skank A8 –Shorty The President Written By – D. Thompson Riding With Mr. Lee B1 –Earl "Chinna" Smith Written-By – Earl "China" Smith* President A Mash Up The Resident B2 –Shorty The President Written By – D. Thompson President Rock B3 –Joe White Written-By – J. White* Dew Of Herman B4 –Bongo Herman & Les* Written-By – Bongo Herman, Les* Give Me The Right B5 –The Heptones Written-By – Unknown Artist Underworld Way B6 –Shorty The President Written-By – Rupie Edwards Christmas Rock B7 –Rupie Edwards Written-By – Rupie Edwards Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Trojan Records Copyright (c) – Trojan Records Marketed By – Trojan Sales Ltd. Pressed By – Adrenalin Mastered At – PRT Studios Credits Design – Steve Barrow, Steve Lane Liner Notes – Steve Barrow Producer – Rupie Edwards (tracks: A2 - A8, B1 - B7) Producer [uncredited] – Bunny Lee (tracks: A1) Remastered By – Malcolm Davies Notes Digitally remastered issue of "Yamaha Skank" with additional tracks. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

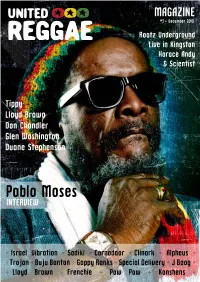

Pablo Moses INTERVIEW

MAGAZINE #3 - December 2010 Rootz Underground Live in Kingston Horace Andy & Scientist Tippy Lloyd Brown Don Chandler Glen Washington Duane Stephenson Pablo Moses INTERVIEW * Israel Vibration * Sadiki * Cornadoor * Clinark * Alpheus * * Trojan * Buju Banton * Gappy Ranks * Special Delivery * J Boog * * Lloyd Brown * Frenchie * Pow Pow * Konshens * United Reggae Mag #3 - December 2010 Want to read United Reggae as a paper magazine? In addition to the latest United Reggae news, views andNow videos you online can... each month you can now enjoy a free pdf version packed with most of United Reggae content from the last month.. SUMMARY 1/ NEWS •Lloyd Brown - Special Delivery - Own Mission Records - Calabash J Boog - Konshens - Trojan - Alpheus - Racer Riddim - Everlasting Riddim London International Ska Festival - Jamaican-roots.com - Buju Banton, Gappy Ranks, Irie Ites, Sadiki, Tiger Records 3 - 9 2/ INTERVIEWS •Interview: Tippy 11 •Interview: Pablo Moses 15 •Interview: Duane Stephenson 19 •Interview: Don Chandler 23 •Interview: Glen Washington 26 3/ REVIEWS •Voodoo Woman by Laurel Aitken 29 •Johnny Osbourne - Reggae Legend 30 •Cornerstone by Lloyd Brown 31 •Clinark - Tribute to Michael Jackson, A Legend and a Warrior •Without Restrictions by Cornadoor 32 •Keith Richards’ sublime Wingless Angels 33 •Reggae Knights by Israel Vibration 35 •Re-Birth by The Tamlins 36 •Jahdan Blakkamoore - Babylon Nightmare 37 4/ ARTICLES •Is reggae dying a slow death? 38 •Reggae Grammy is a Joke 39 •Meet Jah Turban 5/ PHOTOS •Summer Of Rootz 43 •Horace Andy and Scientist in Paris 49 •Red Strip Bold 2010 50 •Half Way Tree Live 52 All the articles in this magazine were previously published online on http://unitedreggae.com.This magazine is free for download at http://unitedreggae.com/magazine/. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures.