Transcript a Pinewood Dialogue with Patricia Rozema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSA Interview MASTER

Amin Bhatia & Ari Posner – Canadian Screen Award Nominees Best Original Music for a Series – X-Company: Black Flag SCGC member Janal Bechthold catches up with the Canadian Screen Award nominees Amin Bhatia and Ari Posner to give you a little look into their process of scoring for the TV series, X-Company. This is their second nomination, having received a Best Original Score nomination for the series in 2016. X-Company is an “emotionally-driven character drama, set in the thrilling and dangerous world of WWII espionage and covert operations. It follows the stories of five highly skilled young recruits.” ~CBC.ca SCGC: How is the premise of X-Company meaningful to you? AB & AP: As a Canadian, to learn about how Camp X in Whitby Ontario and our intelligence forces helped to defeat the Nazi regime was very inspiring. It needs to be said that especially this year we've become acutely aware of world events in the US and how this story is an uncomfortable foreshadowing of what could repeat itself if we do not pay attention. SCGC: What was the biggest challenge you faced during this project? AB & AP: For this particular episode ,"Black Flag", our heroes had to assassinate a high-ranking German general during a night at the Opera. So it created many musical challenges, ranging from ritzy jazz themes and remixes, operatic rearrangements of Gabriel Fauré, ambient terror, orchestral action, and pure tragedy with a Nazi reprisal attack on innocent citizens. Thanks to the co-ordination of the cast and crew we actually wrote the source music months before to be used as playback on set as well as helping the picture editors set the pace and feel of the show. -

Schreef Score Voor Alberta NUMMER

FILMMUZIEKMAGAZINE DANIËL LOHUES – Schreef score voor Alberta NUMMER 191 – 46ste JAARGANG – MAART 2017 1 Score 191 Maart 2017 46ste jaargang ISSN-nummer: 0921- 2612 Het e-zine Score is een uitgave van de stichting FILMMUZIEKMAGAZINE Cinemusica, het Nederlands Centrum voor Filmmuziek REDACTIONEEL Informatienummer: +31 050-5251991 Filmcomponisten hebben allen hun eigen muzikale achter- grond. Meestal gaat een opleiding in de klassieke muziek E-mail: vooraf aan het bestaan van een filmcomponist, althans zo [email protected] denkt het grote publiek nog maar al te vaak. Een treffend voorbeeld is de Amerikaan Aaron Copland die een dergelijke opleiding genoot en naar Hollywood reisde om daar enkele Kernredactie: Paul memorabele scores te schrijven. Dat de werkelijkheid anders Stevelmans en Sijbold kan zijn, bewijzen enkele van de componisten die werden Tonkens genomineerd voor een Oscar dit jaar. De een komt uit de Aan Score 191 werkten avant-gardistische muziekwereld, een ander uit de alternatie- mee: Paul Stevelmans ve popwereld en weer een ander heeft een opleiding in de en Sijbold Tonkens klassieke muziek achter de rug. Dichterbij huis zien we dat Daniël Lohues zijn eigen muzikale Eindredactie: Paul ontwikkeling kent: de singer-songwriter heeft de laatste jaren Stevelmans voorzichtig aan de weg getimmerd als componist voor film. Deze Score begint met een interview met Lohues. Filmmu- ziek betekent niet per definitie een symfonische score, maar Vormgeving: Paul kent vele verschillende stijlen en daar mogen we heel blij mee Stevelmans zijn. Met dank aan: Daniël Lohues, Coen ter Wol- INHOUDSOPGAVE beek, Reyer Boxem (fo- to’s Daniël Lohues), 3 Daniël Lohues - Interview Marco Beltrami, Costa Communications, AMPAS 7 Marco Beltrami - Interview 10 In memoriam: Jan Stoeckart 13 Aaron Copland - Portret 17 Oscar 2017 23 Boekbespreking 24 Recensies 2 VAN IMPROVISATIE NAAR FILMSCORE Daniël Lohues over zijn muziek voor Alberta Als zanger en liedjesschrijver heeft Daniël Lohues al meer dan twee decennia zijn sporen ruimschoots verdiend. -

1. Managing-Director's Report BOD Feb 26 2019

Managing Director’s Report Board of Directors meeting February 26th 2019 Presented/Submitted by Tonya Dedrick Advocacy DM@X Conference • SCGC Board Members Paul Novotny, Amin Bhatia, Ryner Stoetzer, and President John Welsman attended the DM@X conference at the University of Toronto. • Much was presented and discussed about the state of digital media, with a strong sense of urgency about the need for legislative changes around Copyright, the Broadcast Act, streaming services, and dealing with the new realities in a coordinated effort internationally. Programs Orchestral Reading Session (ORS) • The ORS Masterclass took place on December 10th at Hugh’s Room and was a great success. Panelists included: Composers John Welsman, and Rob Carli, Director Don McBrearty and Filmmaker Larry Weinstein. • Once again, tremendous thanks to John Herberman for his dedicated leadership given to this popular program! Programs Interviewing 1010 for Composers #Womeninfilm #ComposeHer Janal Bechthold Chair of our Women Composer Advisory Council, hosted 'Interviewing 101 for Composers'. At this event, Jen Gorman (from GormanPR) walked through PR tips for composers. Educational Outreach • We will be presenting to students at York University on February 28th 2019. • With much appreciation we have Charlie Finlay and Elizabeth Hannan who continue to an outstanding job representing the SCGC and providing students with a basic overview of benefits of membership with the SCGC and how joining the guild can assist them with the next steps of their education and career path. • Many thanks to Nicholas Stirling who administrates the Educational Outreach program. Industry Outreach Whistler Film Festival This year we began a new partnership with the Whistler Film Festival. -

Rossi Laura Rossi's War Musics Kendra Preston Leonard of The

rossi Laura Rossi’s War Musics Kendra Preston Leonard Of the many eminent and acclaimed composers writing today for both film and the concert hall, not just men but also such women as Laura Karpman, Anne Dudley, Lolita Ritmanis, Lesley Barber, and Debbie Wiseman, it is Laura Rossi who is perhaps best known for the intimate connections between her works for the cinema and the stage. Rossi, nominated for an Academy Award for her music for Unfinished Song (2012), was commissioned by the Imperial War Museum (IWM) to compose original scores for films from the period of the Great War, including the 1916 The Battle of the Somme (2008) and 1917 The Battle of the Ancre (2002).i Rossi has also been heralded for her concert works, and in 2014 her work in these two spheres overlapped with the creation of her Voices of Remembrance for orchestra, choir, and spoken voices.ii Voices was composed for the centenary of the First World War, and includes spoken recitations of ten World War I poems, musical settings of three of the poems for voice and orchestra, and seven instrumental movements based on the remaining poems. In reading Rossi’s Voices in the context of her scores for World War I films and analyzing Rossi’s approaches to scoring texts and testimonies of various natures documenting the war, I theorize that Rossi’s Voices of Remembrance differs in approach from her film scores in that it does not function just as music to help audiences understand the context of wartime artistic creations but also seeks to serve as a musical autobiography-by-proxy for the poets upon whose works the work is based. -

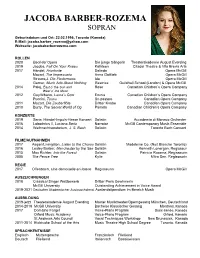

Jacoba Barber-Rozema Soprano

JACOBA BARBER-ROZEMA SOPRAN Geburtsdatum und Ort: 22.02.1996, Toronto (Kanada) E-Mail: [email protected] Webseite: jacobabarberrozema.com ROLLEN 2020 Bechdel Opera Die junge Sängerin Theaterakademie August Everding 2019 Jacobs, Fall On Your Knees Kathleen Citadel Theatre & Vita Brevis Arts 2017 Händel, Ariodante Dalinda Opera McGill Mozart, The Impressario Anna Gottlieb Opera McGill Strauss,J. Die Fledermaus Ida Opera McGill Garner, Much Ado About Nothing Beatrice Guildhall School (London) & Opera McGill 2014 Palej, East o’ the Sun and Rose Canadian Children’s Opera Company West o’ the Moon 2012 Gay/Albano, Laura’s Cow Emma Canadian Children’s Opera Company Puccini, Tosca Un pastore Canadian Opera Company 2011 Mozart, Die Zauberflöte Dritter Knabe Canadian Opera Company 2010 Burry, The Secret World of Og Pamela Canadian Children’s Opera Company KONZERTE 2019 Seria: Händel-Impuls-Hasse Konzert Solistin Accademia di Monaco Orchester 2016 Laborintus II, Luciano Berio Narrator McGill Contemporary Music Ensemble 2014 Weihnachtsoratorium, J. S. Bach Solistin Toronto Bach Consort FILME/AUFNAHMEN 2017 Asgari/Livingston, Listen to the Chorus Solistin Madeleine Co. (Nuit Blanche Toronto) 2016 Lesley Barber, Manchester by the Sea Solistin Kenneth Lonergan, Regisseur 2015 Max Richter, Into the Forest Solistin Patricia Rozema, Regisseurin 2005 The Peace Tree Kylie Mitra Sen, Regisseurin REGIE 2017 Offenbach, Une demoiselle en loterie Regisseurin Opera McGill AUSZEICHNUNGEN 2018 Classical Singer Wettbewerb Dritter Preis Gewinnerin McGill -

Starry 'Sousatzka' Team on Garth Drabinsky's Comeback Musical

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 17, 2016 Women composers US rapper Common on look to even up the movie score teaming up with 13TH s the movie business struggles with diversity and gen- merican rapper Common said it was “very special” to der equality issues, there are signs of progress on the team up again with director Ava DuVernay on her latest Amusic front: At least four features being released Adocumentary “13TH”, which deals with issues of race between now and year’s end have been scored by women, and the US criminal justice system. The Chicago native, who and at least two are expected to be major awards contenders. won a 2015 Academy Award for best song “Glory” from That may not sound like much. But consider this: No female DuVernay’s 1960s civil rights drama “Selma,” said it was impor- composer has been nominated for an original-score Oscar in tant for him to work on her latest project. “I think it’s very, very the past 15 years, and only four women have been nominated special. She is like one of those creative, passionate, intelligent in the entire 81-year history of the category. Two have won: beings and visionaries and is committed. So I’m like always British composers Rachel Portman, for “Emma,” and Anne saying, ok, what can we do?,” Common said in an interview. Dudley, for “The Full Monty.” The documentary argues that although slavery was official- “Rainbow Time,” scored by Heather McIntosh, opened Nov. ly abolished in the United States 150 years ago, it is still alive in 4. -

NEW FILMS from CANADA MARCH 21 – 24, 2019 AMERICAN CINEMATHEQUE at the AERO THEATRE 1328 Montana Avenue at 14Th Street, Santa Monica

NEW FILMS FROM CANADA MARCH 21 – 24, 2019 AMERICAN CINEMATHEQUE AT THE AERO THEATRE 1328 Montana Avenue at 14th Street, Santa Monica Movies on the Big Screen! AMERICAN CINEMATHEQUE.COM CANADA NOW 2019 Look up. Way up. Up above that 49th parallel. Soon you will begin to see the swirling illuminations of those northern cinematic lights: Canada Now 2019 is here. Yes, your Canadian neighbours are again coming south, bringing tales of restless youth, indigenous stories of tragedy and healing, compelling personal dramas about reinventing our world with the power of our imaginations, as well as a riveting documentary about the search for social justice in right here in the United States of America. This latest Canada Now selection includes daring and impressive works by both veteran flmmakers and new Canadian visions by emerging directorial talents. As always, the 2019 Canada Now showcase celebrates the independent spirit that has always been a hallmark of Canadian cinema. Follow us on Facebook at @CanadaNowFilm www.CanadaNowFestival.com Directors of the CANADA NOW flms will be present at screenings for Q & A. The Firefies Are Gone/ La disparition des lucioles THURSDAY, MARCH 21, 7:30 PM DOUBLE FEATURE NIGHT! ► FRIDAY, MARCH 22, 7:30 PM THE FIREFLIES ARE GONE/ THROUGH BLACK SPRUCE LA DISPARITION DES LUCIOLES Director: Don McKellar 2018 | 111 MINUTES | ENGLISH Director: Sébastien Pilote 2018 | 96 MINUTES | FRENCH WITH ENGLISH SUBTITLES A thoughtful and timely dramatic exploration of the crisis in Canada regarding missing and murdered Indigenous women, Through Black Spruce revolves around Annie Bird, On the verge of her high school graduation, a brilliant, high-spirited young 18 year-old a young Cree woman from the remote James Bay region of Northern Ontario who travels woman named Léo can’t wait to get out of her drab small town in Quebec’s hinterland. -

ADAM HAY – BIO and TESTIMONIALS

ADAM HAY – BIO and TESTIMONIALS "Adam Hay is awesome! PASSION and KNOWLEDGE! If I could take lessons from him I would." Paul Bostaph (SLAYER) Born in 1976, Adam Hay is a freelance drummer/drum teacher living in Canada, having played well over 2,000 dates since the early 1990s all over the US and Canada with Quintuple Platinum selling artist Chantal Kreviazuk (Sony/2x Juno Winner/3x Nominee), multiple Diamond (million) selling artistRaine Maida (Sony/Our Lady Peace/4x Juno Winner), Sarah Slean (Warner/Juno Nominee), Justin Rutledge (Six Shooter, Juno Nominee), Martina Sorbara (Mercury/Dragonette, Juno Nominee and Winner), Royal Wood (Dead Daisy/Six Shooter/ Juno Nominee), Patricia O'Callaghan (EMI), John Barrowman (Sony UK), Sharon Cuneta (Sony Philippines), KC Concepcion (Sony Philippines), Jeff Healey (George Harrison/multiple award winner), Dr. Draw, Luisito Orbegoso (Montreal Jazzfest Grand Prix winner), Cindy Gomez, George Koeller (Peter Gabriel/Bruce Cockburn/Dizzy Gillespie), Alexis Baro (David Foster/Paul Schaffer/Tom Jones/Cubanismo) Lesley Barber (composer for Film/TV/’Manchester by the Sea’), Jay Danley (award winner), Sonia Lee (first violinist with Toronto Symphony Orchestra for 6 years/Detroit Symphony Orchestra), Kevin Fox (Celine Dion, Justin Bieber), The Mercenaries, MOKOMOKAI, Leahy, Eric Schenkman (The Spin Doctors) and hundreds more. He has also recorded with producer David Bottrill (Peter Gabriel, Tool, Smashing Pumpkins, Rush). Adam has appeared live on national TV in front of millions of people (MTV, CTV's Canada AM, City TV's Breakfast Television, CBC, Rogers TV, Mike Bullard on CTV) and live radio shows, award ceremonies, TV and Radio commercials as a jingle artist, sold out theaters and festivals, music videos, national TV Season launch parties, many full length albums, record company showcases in the USA and Canada, minuscule cafeterias, to downtown sidewalks as a busker earlier on. -

Mongrel Media Presents

Mongrel Media presents a film by Wiebke von Carolsfeld Best First Canadian Feature, 2002 Toronto International Film Festival Best Screenplay, 2002 Atlantic Film Festival (Canada, 2002, 90 minutes) Distribution 109 Melville Ave. Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6G 1Y3 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR Tel: 416-488-4436 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] CAST Agnes Molly Parker Theresa Rebecca Jenkins Louise Stacy Smith Rose Marguerite McNeil Joanie Ellen Page Chrissy Hollis McLaren Dory Emmy Alcorn Ken Joseph Rutten Valerie Nicola Lipman Marlene Jackie Torrens Sandy Kevin Curran Mickey Ashley MacIsaac Sue Heather Rankin Evie Linda Busby Tavern Bartender Stephen Manuel Airport Bartender Jim Swansberg KEY CREW Distributor Mongrel Media Production Companies Sienna Films / Idlewild Films Director Wiebke von Carolsfeld Writer Daniel MacIvor Producers Jennifer Kawaja Bill Niven Julia Sereny Co-Producer Brent Barclay First Assistant Director Trent Hurry Director of Photography Stefan Ivanov B.A.C. Production Designer Bill Fleming Editor Dean Soltys Costume Designer Martha Currie Makeup Kim Ross Hair Joanne Stamp 2 Synopsis Marion Bridge is the moving story of three sisters torn apart by family secrets. In the midst of struggling to overcome her self-destructive behaviour, the youngest sister, Agnes, returns home determined to confront the past in a community built on avoiding it. Her quest sets in motion a chain of events that allows the sisters each in their own way to re-connect with the world and one another. Set in post-industrial Cape Breton, Marion Bridge is a story of poignant humor and drama. -

Neuerwerbungen Stadtbibliothek Zwickau April 2020

Neuerwerbungen Stadtbibliothek Zwickau April 2020 CD Jazz / Blues Dutronc, T. Dutronc, Thomas: Frenchy / Thomas Dutronc. - Blue Note , 2020. Jazz / Blues Cohen, A. Cohen, Avishai: BIg Vicious / Avishai Cohen. - ECM Records, 2020. Rock / Pop Buddha-Bar XXII Buddha-Bar : XXII - Wagram Music, 2020. Rock / Pop Kontor Kontor : Top Of The Clubs : Volume 85 - Kontor Records, 2020. Rock / Pop Fetenhits 90s Maxi Classics Fetenhits : 90s Maxi Classics - Berlin : Universal Music, 2020. Rock / Pop Fetenhits Rock Classic Fetenhits : Rock Classics - Berlin : Universal Music, 2020. Rock / Pop Lipa, D. Lipa, Dua: Future Nostalgia / Dua Lipa. - Berlin : Universal Music, 2020. Rock / Pop Satriani, J. Satriani, Joe: Shapeshifting / Joe Satriani. - Sony Music Entertainment, 2020. Rock / Pop Soul, B. Soul, Ben l'Oncle: Addicted To You / Ben l'Oncle Soul. - Decca Records, 2020. Rock / Pop Nightwish Nightwish: Human. :II: Nature. / Nightwish. - Nuclear Blast, 2020. Sachliteratur B 500 Sc Schauer, Reinbert: Betriebswirtschaftslehre : Grundlagen / Reinbert Schauer. - Wien : Linde Verlag, 2019. 1 B 500 Am Amely, Tobias: BWL kompakt für Dummies / Tobias Amely ; Koautor bei Kapitel 13: Thomas Krickhahn. - Weinheim : Wiley-VCH, 2018. B 500 Sc Schmalen, Helmut: Grundlagen und Probleme der Betriebswirtschaft / Helmut Schmalen, Hans Pechtl. - Stuttgart : Schäffer-Poeschel , 2019. B 500 Ge Geyer, Helmut: Crashkurs BWL / Helmut Geyer, Bernd Ahrendt. - Freiburg : Haufe-Lexware, 2019. B 500 Ka Kaufmännische Betriebslehre mit Volkswirtschaftslehre : Hauptausgabe / verfasst von Lehrern des kaufmännisch-beruflichen Schulwesens ; Mitarbeiter des Arbeitskreises: Felsch, Stefan [und 5 andere]. - Wuppertal : Europa-Lehrmittel, 2019. B 511 Ha Hammer, Thomas: Existenzgründung / Thomas Hammer. - Berlin : Stiftung Warentest, 2020. B 511 Lu Lutz, Andreas: Existenzgründung : was Sie wirklich wissen müssen ; die 50 wichtigsten Fragen und Antworten / Andreas Lutz, Monika Schuch. -

Comfort Women” Seek a Formal Apology from the Japanese Government, in the Apology, Airing October 22, 2018 on POV

Contacts POV Communications 212-989-7425, [email protected] Adam Segal, Publicist [email protected] POV Pressroom pbs.org/pov/pressroom Three Surviving “Comfort Women” Seek a Formal Apology from the Japanese Government, in The Apology, Airing October 22, 2018 on POV Film depicts the personal journey of three women whose lives were upended when they were forced into sexual slavery during World War II. United Nations researchers report that between 1931 and 1945, the Japanese military forced an estimated 200,000 to 400,000 women and girls into institutionalized sexual slavery. Euphemistically referred to as “comfort women,” they typically ranged in age from 11 to 33 and were taken from Japanese colonies from Korea to Indonesia. Mobilized through forced recruitment, kidnapping, false employment offers or sale by family members and employers, they served in brothels supervised by the Japanese military. Seventy years after their imprisonment, the surviving “comfort women” still await an official apology from the government of Japan. Writer/director Tiffany Hsiung’s film The Apology follows the personal journeys of three surviving “comfort women”—or “grandmothers”—Grandma Gil in South Korea, Grandma Cao in China and Grandma Adela in the Philippines. Facing fading health in their twilight years, they grapple with the impact of their wartime experiences and the legacy they will leave behind. Summarizing the stakes, Grandma Gil says, “Once we resolve the comfort women situation, the war can finally come to an end.” The Apology has its national broadcast premiere on the PBS documentary series POV (Point of View) on Monday, October 22, 2018. POV is American television’s longest-running independent documentary series, now in its 31st season. -

Bibliographie Der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020)

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Hans Jürgen Wulff; Ludger Kaczmarek Bibliographie der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014– 2020) 2020 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14981 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wulff, Hans Jürgen; Kaczmarek, Ludger: Bibliographie der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020). Westerkappeln: DerWulff.de 2020 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 197). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14981. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0197_20.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 197, 2020: Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020). Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Hans J. Wulff u. Ludger Kaczmarek. ISSN 2366-6404. URL: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0197_20.pdf. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Letzte Änderung: 19.10.2020. Bibliographie der Filmmusik: Ergänzungen II (2014–2020) Zusammengestell !on "ans #$ %ul& und 'udger (aczmarek Mit der folgenden Bibliographie stellen wir unseren Leser_innen die zweite Fortschrei- bung der „Bibliographie der Filmmusik“ vor die wir !""# in Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere $#% !""#& 'rgänzung )* +,% !"+-. begr/ndet haben. 1owohl dieser s2noptische 3berblick wie auch diverse Bibliographien und Filmographien zu 1pezialproblemen der Filmmusikforschung zeigen, wie zentral das Feld inzwischen als 4eildisziplin der Musik- wissenscha5 am 6ande der Medienwissenschaft mit 3bergängen in ein eigenes Feld der Sound Studies geworden ist.