Michael Casey's Obscenities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Spiritual Journey in the Poetry of Theodore Roethke

THE SPIRITUAL JOURNEY IN THE POETRY OF THEODORE ROETHKE APPROVED: Major Professor Minor Professor Chairman of thfe Department of English. Dean of the Graduate School /th. A - Neiman, Marilyn M., The Spiritual Journey in the Poetry of Theodore Roethke. Master of Arts (English), August, 1971 j 136 pp., "bibliography. If any interpretation of Theodore Roethke's poetry is to be meaningful, it must be made in light of his life. The sense of psychological guilt and spiritual alienation that began in childhood after his father's death was intensified in early adulthood by his struggles with periodic insanity. Consequently, by the time he reached middle age, Theodore Roethke was embroiled in an internal conflict that had been developing over a number of years, and the ordering of this inner chaos became the primary goal in his life, a goal which he sought through the introspection within his poetry. The Lost Son and Praise to the End I represent the con- clusion of the initial phases of Theodore RoethkeTs spiritual- journey. In most of the poetry in the former volume, he experjments with a system of imagery and symbols to be used in the Freudian and Jungian exploration of his inner being. In the latter volume he combines previous techniques and themes in an effort to attain a sense of internal peace, a peace attained by experiencing a spiritual illumination through the reliving of childhood memories. However, any illumination that Roethke experiences in the guise of his poetic protagonists is only temporary, 'because he has not yet found a way to resolve his psychological and spiritual conflicts. -

Librarian of Congress Appoints UNH Professor Emeritus Charles Simic Poet Laureate

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Media Relations UNH Publications and Documents 8-2-2007 Librarian Of Congress Appoints UNH Professor Emeritus Charles Simic Poet Laureate Erika Mantz UNH Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/news Recommended Citation Mantz, Erika, "Librarian Of Congress Appoints UNH Professor Emeritus Charles Simic Poet Laureate" (2007). UNH Today. 850. https://scholars.unh.edu/news/850 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the UNH Publications and Documents at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Relations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Librarian Of Congress Appoints UNH Professor Emeritus Charles Simic Poet Laureate 9/11/17, 1250 PM Librarian Of Congress Appoints UNH Professor Emeritus Charles Simic Poet Laureate Contact: Erika Mantz 603-862-1567 UNH Media Relations August 2, 2007 Librarian of Congress James H. Billington has announced the appointment of Charles Simic to be the Library’s 15th Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry. Simic will take up his duties in the fall, opening the Library’s annual literary series on Oct. 17 with a reading of his work. He also will be a featured speaker at the Library of Congress National Book Festival in the Poetry pavilion on Saturday, Sept. 29, on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. Simic succeeds Donald Hall as Poet Laureate and joins a long line of distinguished poets who have served in the position, including most recently Ted Kooser, Louise Glück, Billy Collins, Stanley Kunitz, Robert Pinsky, Robert Hass and Rita Dove. -

WINTER 1977-78 David Wagoner Janis LUI.I

~©~«E >+~i " ':~UM~'.:4',":--+:@e TBe:,.".tev1-7a C 0 ',.' z>i 4 ' 8k .'"Agf' '" „,) „"p;44M P POET RY g + NORTHWEST VOLUME EIGHTEEN NUMBER FOUR EDITOR WINTER 1977-78 David Wagoner JANIs LUI.I. T hree Poems.. 3 EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS CAROLE OLES Nelson Bentley, William H. Matchett Four Poems CONRAD HILBERBY Script for a Cold Chris tmas. .. JOHN UNTERECKEB COVER DESIGN Two Poems Allen Auvil 10 VICTOR TRELAwNY What the Land Offers . FRED MURATORI Confessional Poem Coverfrom a photograph of an osprey's nest RONALD WALLACE near the Snoqttatmie River in Washington State. Three Poems 13 CAROLYNE W R IGH T 613 15 CABoL McCoBMMAGH Rough Drafts 16 ALVIN GREENBERG BOARD OF ADvISERS poem beginning with 'b eginning' and ending with 'ending' Leonie Adams, Robert Fitzgerald, Robert B. Heilman, MARK ABMAN Stanley Kunitz, J Jackson Mathews, Arnold Stein Writing for Nora 18 RON SLATE Pastorale. 19 JOHN C. WITTE POETRY NORTHWEST WI N TER 1977-78 VOL UME XVIII, NUMBER 4 Two Poems 20 Published quarterly by the University of Washington. Subscriptions and manu WILL WELLS scripts should be sent to Poetry Northwest, 4045 Brooklyn Avenue NE, Univer Two Poems 21 sity of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98105. Not responsible for unsolicited MARJORIE HAWKSWORTH manuscripts; all submissions must be accompanied by a stamped self-addressed I Never Clean It. envelope. Subscription rates: U.S., $5.00 per year, single copies $1.50; Canada, $6.00 per year, single copies $1.75. VASSAR MILLER Two Poems © 1978 by the University of Washington SANDRA MCPHERSON Two Poems . 24 Distributed by B. DeBoer, 188 High Street, Nutley, N.J. -

Gallery&Studio Arts Journal

Gallery&Studio arts journal In this Issue: The new G&S Arts Journal was set up to give a voice to those who are not heard, those who need a wider platform, a larger amplifier. Therefore, as we celebrate Black History Month in February and Women’s History Month in March, here in the United States, we have turned a special spotlight on these two groups for this issue. That is not to say that we do this to the exclusion of others, nor do we forget these groups throughout the year. Our hope is that by sharing the arts, we learn to value individuality as well as finding compassion and a generosity of spirit towards humanity. As this second print issue sees the light of day, we extend our thanks to all our wonderful donors who have already shown that spirit of generosity. We couldn’t do this without you. We would particularly like to give special thanks our newest board member, who wishes to remain anonymous, whose donation made our first print issue possible. —The Editors Cover image: “On Fire” ©Xenia Hausner, Courtesy of Forum Gallery, New York Gallery&Studio arts journal PUBLISHED BY ©G&S Arts Journal Inc. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 1632 First Avenue, Suite 122, New York, NY 10028 email: [email protected] EDITOR AND PUBLISHER Jeannie McCormack MANAGING EDITOR Ed McCormack OPERATIONS Marina Hadley SPECIAL EDITORIAL ADVISOR Margot Palmer-Poroner SPECIAL ADVISOR Dorothy Beckett POETRY EDITOR Christine Graff DESIGN AND PRODUCTION Karen Mullen TECHNICAL CONSULTANT Sébastien Aurillon WEBSITE galleryand.studio BOARD OF DIRECTORS Sébastien Aurillon, Christine Graf, Marina Hadley, Antonio Huerta Jeannie McCormack, Carolyn Mitchell, Margot Palmer-Poroner, Norman Ross Gallery&Studio Arts Journal is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization and distributes its journal free of charge in the New York City area. -

Poetry for the People

06-0001 ETF_33_43 12/14/05 4:07 PM Page 33 U.S. Poet Laureates P OETRY 1937–1941 JOSEPH AUSLANDER FOR THE (1897–1965) 1943–1944 ALLEN TATE (1899–1979) P EOPLE 1944–1945 ROBERT PENN WARREN (1905–1989) 1945–1946 LOUISE BOGAN (1897–1970) 1946–1947 KARL SHAPIRO BY (1913–2000) K ITTY J OHNSON 1947–1948 ROBERT LOWELL (1917–1977) HE WRITING AND READING OF POETRY 1948–1949 “ LEONIE ADAMS is the sharing of wonderful discoveries,” according to Ted Kooser, U.S. (1899–1988) TPoet Laureate and winner of the 2005 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry. 1949–1950 Poetry can open our eyes to new ways of looking at experiences, emo- ELIZABETH BISHOP tions, people, everyday objects, and more. It takes us on voyages with poetic (1911–1979) devices such as imagery, metaphor, rhythm, and rhyme. The poet shares ideas 1950–1952 CONRAD AIKEN with readers and listeners; readers and listeners share ideas with each other. And (1889–1973) anyone can be part of this exchange. Although poetry is, perhaps wrongly, often 1952 seen as an exclusive domain of a cultured minority, many writers and readers of WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS (1883–1963) poetry oppose this stereotype. There will likely always be debates about how 1956–1958 transparent, how easy to understand, poetry should be, and much poetry, by its RANDALL JARRELL very nature, will always be esoteric. But that’s no reason to keep it out of reach. (1914–1965) Today’s most honored poets embrace the idea that poetry should be accessible 1958–1959 ROBERT FROST to everyone. -

NEA Chronology Final

THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 1965 2000 A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY OF FEDERAL SUPPORT FOR THE ARTS President Johnson signs the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act, establishing the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, on September 29, 1965. Foreword he National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act The thirty-five year public investment in the arts has paid tremen Twas passed by Congress and signed into law by President dous dividends. Since 1965, the Endowment has awarded more Johnson in 1965. It states, “While no government can call a great than 111,000 grants to arts organizations and artists in all 50 states artist or scholar into existence, it is necessary and appropriate for and the six U.S. jurisdictions. The number of state and jurisdic the Federal Government to help create and sustain not only a tional arts agencies has grown from 5 to 56. Local arts agencies climate encouraging freedom of thought, imagination, and now number over 4,000 – up from 400. Nonprofit theaters have inquiry, but also the material conditions facilitating the release of grown from 56 to 340, symphony orchestras have nearly doubled this creative talent.” On September 29 of that year, the National in number from 980 to 1,800, opera companies have multiplied Endowment for the Arts – a new public agency dedicated to from 27 to 113, and now there are 18 times as many dance com strengthening the artistic life of this country – was created. panies as there were in 1965. -

Dreams of Earth and Sky: Interviews with Nine Kansas Poets

DREAMS OF EARTH AND SKY: INTERVIEWS WITH NINE KANSAS POETS By Copyright 2010 Kirsten Ann Meenen Bosnak M.S., University of Kansas, 1993 Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts. Committee members: _____________________________________________ Chairperson, Michael L. Johnson _____________________________________________ Joseph Harrington _____________________________________________ Denise Low Date defended _________________________________ ii The Thesis Committee for Kirsten Ann Meenen Bosnak certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: DREAMS OF EARTH AND SKY: INTERVIEWS WITH NINE KANSAS POETS Committee members: ____________________________________________ Chairperson, Michael L. Johnson ____________________________________________ Joseph Harrington ____________________________________________ Denise Low Date approved ________________________________ ii i Abstract This thesis comprises interviews with nine poets who have a Kansas background and whose work exhibits a strong sense of place. The interviews took place during the period running from April 2008 through May 2009. The conversations explore the practice and process of writing; the poets’ influences; the shift in consciousness, from adolescence through maturity, about various aspects of writing; ideas about the purpose and value of poetry; and the intersection of the poets’ personal experiences with their writing. Each of the poets interviewed has some connection to the poet William Stafford, who grew up in Kansas, attended the University of Kansas, and in 1970 was Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1970, the position that later became U.S. Poet Laureate. Stafford’s influence on several of these poets is strong. His influence is explored in several interviews and is an important subject of the collection as a whole. -

Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle

LiteraryChautauqua & Scientific Circle Founded in Chautauqua, New York, 1878 Book List 1878 – 2018 A Brief History of the CLSC “Education, once These are the words of Bishop John Heyl Vincent, cofounder the peculiar with Lewis Miller of the Chautauqua Institution. They are privilege of the from the opening paragraphs of his book, The Chautauquan few, must in Movement, and represent an ideal he had for Chautauqua. To our best earthly further this Chautauquan ideal and to disseminate it beyond estate become the physical confines of the Bishop John Heyl Vincent Chautauqua Institution, Bishop the valued Vincent conceived the idea of possession of the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle (CLSC), and founded it in 1878, four years after the founding of the the many.” Chautauqua Institution. At its inception, the CLSC was basically a four year course of required reading. The original aims of the CLSC were twofold: To promote habits of reading and study in nature, art, science, and in secular and sacred literature and To encourage individual study, to open the college world to persons unable to attend higher institution of learning. On August 10, 1878, Dr. Vincent announced the organization of the CLSC to an enthusiastic Chautauqua audience. Over 8,400 people enrolled the first year. Of those original enrollees, 1,718 successfully completed the reading course, the required examinations and received their diplomas on the first CLSC Recognition Day in 1882. The idea spreads and reading circles form. As the summer session closed in 1878, Chautauquans returned to their homes and involved themselves there in the CLSC reading program. -

Richard Wilbur's War and His Poetry

Joseph T. Cox "Versifying in Earnest" Richard Wilbur's War and His Poetry mong Richard Wilbur's many merits are skillful ele- A gance, the intricate coherence of his art, his intelli- gence and wit, and, as Professor Brooker has pointed out, his "sacramental approach" to art and nature (529). I propose that Richard Wilbur's graceful craftsmanship and his rage for order within the lines of his work and in his vision of the world are, in part, a legacy of his World War I1 experience. His comments to Stanley Kunitz that "it was not until World War I1 took me to Cassino, Anzio, and the Siegfried Line that I began to versify in earnest" invites this thesis, a closer look at the detaiIs of his war, and speculation as to the effect of war on his poetic imagination (1808). His first book, The Benufifil Clznnges, includes eight poems that deal specifically with the war, and in them Wilbur realizes his observation that, "One does not use poetry for its major purposes, as a means of organizing oneself and the world, until one's world somehow gets out of hand" (1808). Mr. Wilbur's biography tells us that he served as a cryptographer with the US Army's 36th Infantry Division in Africa, southern France, Italy, and along the Siegfried Line in Germany. What that notation doesn't tell us is the particular intensity of Richard Wilbur's combat expe- rience with a notoriously "hard luck'' infantry division and his use of poetry to organize that chaotic worId. There is, I think, a profound connection between Wilbur's war experience and the deep sincerity and pol- ished formalism of his poetic work. -

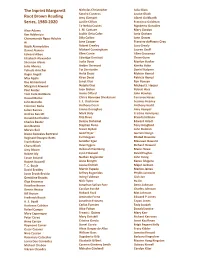

The Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series, 1980-2020

The Inprint Margarett Nicholas Christopher Julia Glass Sandra Cisneros Louise Glück Root Brown Reading Amy Clampitt Albert Goldbarth Series, 1980-2020 Lucille Clifton Francisco Goldman Ta-Nehisi Coates Rigoberto González Alice Adams J. M. Coetzee Mary Gordon Kim Addonizio Judith Ortiz Cofer Jorie Graham Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Billy Collins John Graves Ai Jane Cooper Francine duPlessix Gray Rabih Alameddine Robert Creeley Lucy Grealy Daniel Alarcón Michael Cunningham Lauren Groff Edward Albee Ellen Currie Allen Grossman Elizabeth Alexander Edwidge Danticat Thom Gunn Sherman Alexie Lydia Davis Marilyn Hacker Julia Alvarez Amber Dermont Kimiko Hahn Yehuda Amichai Toi Derricotte Daniel Halpern Roger Angell Anita Desai Mohsin Hamid Max Apple Kiran Desai Patricia Hampl Rae Armantrout Junot Díaz Ron Hansen Margaret Atwood Natalie Diaz Michael S. Harper Paul Auster Joan Didion Robert Hass Toni Cade Bambara Annie Dillard John Hawkes Russell Banks Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni Terrance Hayes John Banville E. L. Doctorow Seamus Heaney Coleman Barks Anthony Doerr Anthony Hecht Julian Barnes Emma Donoghue Amy Hempel Andrea Barrett Mark Doty Cristina Henríquez Donald Barthelme Rita Dove Brenda Hillman Charles Baxter Denise Duhamel Edward Hirsch Ann Beattie Stephen Dunn Tony Hoagland Marvin Bell Stuart Dybek John Holman Diane Gonzales Bertrand Geoff Dyer Garrett Hongo Reginald Dwayne Betts Esi Edugyan Khaled Hosseini Frank Bidart Jennifer Egan Maureen Howard Chana Bloch Dave Eggers Richard Howard Amy Bloom Deborah Eisenberg Marie Howe Robert Bly Lynn Emanuel David Hughes Eavan Boland Nathan Englander John Irving Robert Boswell Anne Enright Kazuo Ishiguro T. C. Boyle Louise Erdrich Major Jackson David Bradley Martin Espada Marlon James Lucie Brock-Broido Jeffrey Eugenides Phyllis Janowitz Geraldine Brooks Irving Feldman Gish Jen Olga Broumas Nick Flynn Ha Jin Rosellen Brown Jonathan Safran Foer Denis Johnson Dennis Brutus Carolyn Forché Charles Johnson Bill Bryson Richard Ford Mat Johnson Frederick Busch Aminatta Forna Edward P. -

Representative Town Meeting Final Minutes; April 2

RTM Meeting April 2, 2013 The call 1. To take such action as the meeting may determine to elect a Deputy Moderator of the Representative Town Meeting. 2. To take such action as the meeting may determine, upon the recommendation of the RTM Rules Committee, to approve an amendment to Section 22-1 of the Code of Ordinances, establishing new voting districts following the 2010 Census as provided in Section C5-2 of the Town Charter. (Second reading.) Minutes Moderator Eileen Flug: Good evening. This meeting of Westport’s Representative Town Meeting is now called to order. We welcome those who are joining us tonight in the Town Hall auditorium, as well as those watching us streaming live on westportct.gov, and those watching on Cable Channel 79 or AT&T channel 99. My name is Eileen Lavigne Flug and I am the RTM Moderator taking over for our esteemed colleague Hadley Rose who has resigned to move to Simsbury. On my right is RTM Secretary Jackie Fuchs. Tonight’s invocation will be delivered by the Reverend Frank Hall. Invocation, Reverend Frank Hall: I chose a poem from Stanley Kunitz, not as well known as some of the better known poets, Robert Frost and Carl Sandburg, but just as good. He was elected poet laureate, elected to that position when he 95 years old in 2000 because he died at 100, almost 101. I chose this poem because of you, because of what you do and what I do, too. It’s called The Layers: I have walked through many lives, some of them my own, and I am not who I was, though some principle of being abides, from which I struggle not to stray. -

I He Norton Anthology Or Poetry FOURTH EDITION

I he Norton Anthology or Poetry FOURTH EDITION •••••••••••< .•' .'.•.;';;/';•:; Margaret Ferguson > . ' COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY >':•! ;•/.'.'":•:;•> Mary Jo Salter MOUNT HOLYOKE COLLEGE Jon Stallworthy OXFORD UNIVERSITY W. W. NORTON & COMPANY • New York • London Contents PREFACE TO THE FOURTH EDITION lv Editorial Procedures ' Ivi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS " lix VERSIFICATION lxi Rhythm lxii Meter lxii Rhyme lxix Forms Ixxi Basic Forms Ixxi Composite Forms lxxvi Irregular Forms Ixxvii Open Forms or Free Verse lxxviii Further Reading lxxx GEDMON'S HYMN (translated by John Pope) 1 FROM BEOWULF (translated by Edwin Morgan) 2 RIDDLES (translated by Richard Hamer) 7 1 ("I am a lonely being, scarred by swords") 7 2 ("My dress is silent when I tread the ground") 8 3 ("A moth ate words; a marvellous event") 8 THE WIFE'S LAMENT (translated by Richard Hamer) 8 THE SEAFARER (translated by Richard Hamer) 10 ANONYMOUS LYRICS OF THE THIRTEENTH AND FOURTEENTH CENTURIES 13 Now Go'th Sun Under Wood 13 The Cuckoo Song 13 Ubi Sunt Qui Ante Nos Fuerunt? 13 Alison 15 Fowls in the Frith 16 • I Am of Ireland 16 GEOFFREY CHAUCER (ca. 1343-1400) 17 THE CANTERBURY TALES 17 The General Prologue 17 The Pardoner's Prologue and Tale 37 The Introduction 37 The Prologue 38 VI • CONTENTS The Tale 41 The Epilogue 50 From Troilus and Criseide 52 Cantus Troili 52 LYRICS AND OCCASIONAL VERSE 52 To Rosamond 52 Truth 53 Complaint to His Purse 54 To His Scribe Adam 5 5 PEARL, 1-5 (1375-1400) 55 WILLIAM LANGLAND(fl. 1375) 58 Piers Plowman, lines 1-111 58 CHARLES D'ORLEANS (1391-1465) 62 The Smiling Mouth 62 Oft in My Thought 62 ANONYMOUS LYRICS OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY 63 Adam Lay I-bounden 63 I Sing of a Maiden 63 Out of Your Sleep Arise and Wake 64 I Have a Young Sister 65 I Have a Gentle Cock 66 Timor Mortis 66 The Corpus Christi Carol 67 Western Wind 68 A Lyke-Wake Dirge 68 A Carol of Agincourt 69 The Sacrament of the Altar 70 See! here, my heart 70 WILLIAM DUNBAR (ca.