The P-51 Mustang 1 the Inspiration, Design and Legacy Behind the P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P-38J Over Europe 1170 US WWII FIGHTER 1:48 SCALE PLASTIC KIT

P-38J over Europe 1170 US WWII FIGHTER 1:48 SCALE PLASTIC KIT intro The Lockheed P-38 Lightning was developed to a United States Army Air Corps requirement. It became famous not only for its performance in the skies of WWII, but also for its unusual appearance. The Lightning, designed by the Lockheed team led by Chief Engineer Clarence 'Kelly' Johnson, was a complete departure from conventional airframe design. Powered by two liquid cooled inline V-1710 engines, it was almost twice the size of other US fighters and was armed with four .50 cal. machine guns plus a 20 mm cannon, giving the Lightning not only the firepower to deal with enemy aircraft, but also the capability to inflict heavy damage on ships. The first XP-38 prototype, 37-457, was built under tight secrecy and made its maiden flight on January 27, 1939. The USAAF wasn´t satisfied with the big new fighter, but gave permission for a transcontinental speed dash on February 11, 1939. During this event, test pilot Kelsey crashed at Mitchell Field, NY. Kelsey survived the cash but the airplane was written off. Despite this, Lockheed received a contract for thirteen preproduction YP-38s. The first production version was the P-38D (35 airplanes only armed with 37mm cannon), followed by 210 P-38Es which reverted back to the 20 mm cannon. These planes began to arrive in October 1941 just before America entered World War II. The next versions were P-38F, P-38G, P-38H and P-38J. The last of these introduced an improved shape of the engine nacelles with redesigned air intakes and cooling system. -

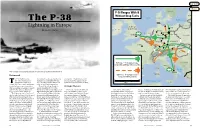

The P-38 Lightning in Europe

Buy Now! Home The P-38 Lightning in Europe By Jonathan Lupton With one engine out and a propeller feathered, a P-38 flies home protected by heavily-armed B-17s. Background he P-38 Lightning was short, it’s almost always described as assumption—that bombers could one of the world’s fastest having been overshadowed by the protect themselves against enemy T aircraft when it first flew P-51 Mustang, a fighter that proved fighter interceptors—wasn’t working. early in 1939. Its eccentric design was to be an ideal long-range escort. immediately seen as exciting rather It would be wrong, though, to Strategic Dilemma than off-putting: its airframe featured simply downplay the P-38. They twin “booms” and a cockpit “pod” provided the bulk of long-range escort Prior to the war the US Army Air Air Corps doctrine further boxes,” could defeat German intercep- P-47 Thunderbolt fighters helped, but in place of a traditional fuselage. fighters during the critical operations Corps (the USAAF’s prewar organi- mandated bombers alone would tor attacks. By the late summer of 1943, they couldn’t escort the bombers all The Lightning was, in fact, one of of January through March 1944, the zational predecessor) had developed dominate future air war. Its leaders that view was clearly out of date. the way to targets deep in Germany. the US Army Air Force’s (USAAF) most decisive period during which the the strategic doctrine of “daylight shared the view of most air com- In fact, as early as 1940 the Battle The USAAF therefore began experi- important aircraft during the war. -

P-38 Lightning

P-38 Lightning P-38 Lightning Type Heavy fighter Manufacturer Lockheed Designed by Kelly Johnson Maiden flight 27 January 1939 Introduction 1941 Retired 1949 Primary user United States Army Air Force Produced 1941–45 Number built 10,037[1] Unit cost US$134,284 when new[2] Variants Lockheed XP-49 XP-58 Chain Lightning The Lockheed P-38 Lightning was a World War II American fighter aircraft. Developed to a United States Army Air Corps requirement, the P-38 had distinctive twin booms with forward-mounted engines and a single, central nacelle containing the pilot and armament. The aircraft was used in a number of different roles, including dive bombing, level bombing, ground strafing, photo reconnaissance missions,[3] and extensively as a long-range escort fighter when equipped with droppable fuel tanks under its wings. The P-38 was used most extensively and successfully in the Pacific Theater of Operations and the China-Burma-India Theater of Operations, where it was flown by the American pilots with the highest number of aerial victories to this date. The Lightning called "Marge" was flown by the ace of aces Richard Bong who earned 40 victories. Second with 38 was Thomas McGuire in his aircraft called "Pudgy". In the South West Pacific theater, it was a primary fighter of United States Army Air Forces until the appearance of large numbers of P-51D Mustangs toward the end of the war. [4][5] 1 Design and development Lockheed YP-38 (1943) Lockheed designed the P-38 in response to a 1937 United States Army Air Corps request for a high- altitude interceptor aircraft, capable of 360 miles per hour at an altitude of 20,000 feet, (580 km/h at 6100 m).[6] The Bell P-39 Airacobra and the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk were also designed to meet the same requirements. -

Aircraft Collection

A, AIR & SPA ID SE CE MU REP SEU INT M AIRCRAFT COLLECTION From the Avenger torpedo bomber, a stalwart from Intrepid’s World War II service, to the A-12, the spy plane from the Cold War, this collection reflects some of the GREATEST ACHIEVEMENTS IN MILITARY AVIATION. Photo: Liam Marshall TABLE OF CONTENTS Bombers / Attack Fighters Multirole Helicopters Reconnaissance / Surveillance Trainers OV-101 Enterprise Concorde Aircraft Restoration Hangar Photo: Liam Marshall BOMBERS/ATTACK The basic mission of the aircraft carrier is to project the U.S. Navy’s military strength far beyond our shores. These warships are primarily deployed to deter aggression and protect American strategic interests. Should deterrence fail, the carrier’s bombers and attack aircraft engage in vital operations to support other forces. The collection includes the 1940-designed Grumman TBM Avenger of World War II. Also on display is the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a true workhorse of the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and Grumman A-6 Intruder, stalwarts of the Vietnam War. Photo: Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum GRUMMAN / EASTERNGRUMMAN AIRCRAFT AVENGER TBM-3E GRUMMAN/EASTERN AIRCRAFT TBM-3E AVENGER TORPEDO BOMBER First flown in 1941 and introduced operationally in June 1942, the Avenger became the U.S. Navy’s standard torpedo bomber throughout World War II, with more than 9,836 constructed. Originally built as the TBF by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, they were affectionately nicknamed “Turkeys” for their somewhat ungainly appearance. Bomber Torpedo In 1943 Grumman was tasked to build the F6F Hellcat fighter for the Navy. -

F—18 Navy Air Combat Fighter

74 /2 >Af ^y - Senate H e a r tn ^ f^ n 12]$ Before the Committee on Appro priations (,() \ ER WIIA Storage ime nts F EB 1 2 « T H e -,M<rUN‘U«sni KAN S A S S F—18 Na vy Air Com bat Fighter Fiscal Year 1976 th CONGRESS, FIRS T SES SION H .R . 986 1 SPECIAL HEARING F - 1 8 NA VY AIR CO MBA T FIG H TER HEARING BEFORE A SUBC OMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE NIN ETY-FOURTH CONGRESS FIR ST SE SS IO N ON H .R . 9 8 6 1 AN ACT MAKIN G APP ROPR IA TIO NS FO R THE DEP ARTM EN T OF D EFEN SE FO R T H E FI SC AL YEA R EN DI NG JU N E 30, 1976, AND TH E PE RIO D BE GIN NIN G JU LY 1, 1976, AN D EN DI NG SEPT EM BER 30, 1976, AND FO R OTH ER PU RP OSE S P ri nte d fo r th e use of th e Com mittee on App ro pr ia tio ns SPECIAL HEARING U.S. GOVERNM ENT PRINT ING OFF ICE 60-913 O WASHINGTON : 1976 SUBCOMMITTEE OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS JOHN L. MCCLELLAN, Ark ans as, Chairman JOH N C. ST ENN IS, Mississippi MILTON R. YOUNG, No rth D ako ta JOH N O. P ASTORE, Rhode Island ROMAN L. HRUSKA, N ebraska WARREN G. MAGNUSON, Washin gton CLIFFORD I’. CASE, New Je rse y MIK E MANSFIEL D, Montana HIRAM L. -

Representative John M. Rogers 60Th House District Sponsor Testimony

Representative John M. Rogers 60th House District Sponsor Testimony - House Bill 687 Chairman Green, Vice Chair Patton, Ranking Member Sheehy, and members of the House Transportation and Public Safety Committee. Thank you for allowing me the opportunity to testify today in support of House Bill 687, legislation that would honor one of our Nations most decorated World War II flying aces, by designating the bridge extending over the Grand River and into Fairport Harbor as the Colonel Donald Blakeslee Bridge. Col. Donald James Matthew Blakeslee was born in 1917 in Fairport Harbor, a small town of 3000 residents nestled along the Grand River and Lake Erie shorelines in my district in Lake County. As a young boy, Blakeslee became interested in flying after attending the Cleveland Air Races. In 1938 Blakeslee joined the Army Air Corps Reserve. In 1939, with the onset of World War II in the European Theater, the United States would remain on the sidelines for another 2 years. Eager to fight for the Allies, Blakeslee joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1939 and traveled to England. While serving with the No. 401 Squadron of the RCAF in the early stages of the war, Blakeslee would prove himself as a talented Spitfire pilot and a gifted flight leader, flying a large number of sorties over enemy territory and destroying or damaging multiple enemy aircraft. In August of 1942, Blakeslee became a flying “ace” after a destroying an aircraft during a raid in France. With the creation of the United States Army Air Force in 1942, Blakeslee decided to leave the RCAF and transfer back into an American unit. -

Guide to Aces and Heroes ■ 2013 USAF Almanac Major Decorations

Guide to Aces and Heroes ■ 2013 USAF Almanac Major Decorations USAF Recipients of the Medal of Honor Name and Rank at Time of Action Place of Birth Date of Action Place of Action World War I Bleckley, 2nd Lt. Erwin R. Wichita, Kan. Oct. 6, 1918 Binarville, France Goettler, 1st Lt. Harold E. Chicago Oct. 6, 1918 Binarville, France Luke, 2nd Lt. Frank Jr. Phoenix Sept. 29, 1918 Murvaux, France Rickenbacker, 1st Lt. Edward V. Columbus, Ohio Sept. 25, 1918 Billy, France World War II Baker, Lt. Col. Addison E. Chicago Aug. 1, 1943 Ploesti, Romania Bong, Maj. Richard I. Superior, Wis. Oct. 10-Nov. 15, 1944 Southwest Pacific Carswell, Maj. Horace S. Jr. Fort Worth, Tex. Oct. 26, 1944 South China Sea Castle, Brig. Gen. Frederick W. Manila, Philippines Dec. 24, 1944 Liège, Belgium Cheli, Maj. Ralph San Francisco Aug. 18, 1943 Wewak, New Guinea Craw, Col. Demas T. Traverse City, Mich. Nov. 8, 1942 Port Lyautey, French Morocco Doolittle, Lt. Col. James H. Alameda, Calif. April 18, 1942 Tokyo Erwin, SSgt. Henry E. Adamsville, Ala. April 12, 1945 Koriyama, Japan Femoyer, 2nd Lt. Robert E. Huntington, W.Va. Nov. 2, 1944 Merseburg, Germany Gott, 1st Lt. Donald J. Arnett, Okla. Nov. 9, 1944 Saarbrücken, Germany Hamilton, Maj. Pierpont M. Tuxedo Park, N.Y. Nov. 8, 1942 Port Lyautey, French Morocco Howard, Lt. Col. James H. Canton, China Jan. 11, 1944 Oschersleben, Germany Hughes, 2nd Lt. Lloyd H. Alexandria, La. Aug. 1, 1943 Ploesti, Romania Harold Goettler Frank Luke Frederick Castle AIR FORCE Magazine / May 2013 119 Neel Kearby Louis Sebille George Day* *Living Medal of Honor recipient World War II (continued) Jerstad, Maj. -

Bombing the European Axis Powers a Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945

Inside frontcover 6/1/06 11:19 AM Page 1 Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 Air University Press Team Chief Editor Carole Arbush Copy Editor Sherry C. Terrell Cover Art and Book Design Daniel M. Armstrong Composition and Prepress Production Mary P. Ferguson Quality Review Mary J. Moore Print Preparation Joan Hickey Distribution Diane Clark NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page i Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 RICHARD G. DAVIS Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2006 NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page ii Air University Library Cataloging Data Davis, Richard G. Bombing the European Axis powers : a historical digest of the combined bomber offensive, 1939-1945 / Richard G. Davis. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-148-1 1. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations. 2. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations––Statistics. 3. United States. Army Air Forces––History––World War, 1939- 1945. 4. Great Britain. Royal Air Force––History––World War, 1939-1945. 5. Bombing, Aerial––Europe––History. I. Title. 940.544––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Book and CD-ROM cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page iii Contents Page DISCLAIMER . -

Usaf Unit Histories – Higher Commands

USAF UNIT HISTORIES – HIGHER 010380 FIGHTER LOSSES OF THE MIGHTY EIGHTH by William H Adams. A Chronological COMMANDS Survey of Spitfire, P-38, P-47 and P-51 Losses, 8th USAF July 1942 – April 1945. An 8th AF Memorial 010353 HEAVY BOMBERS TO THE MIGHTY museum Foundation Publication, 1995. Spiral bound, TH 8 : Historical survey of B-17’s/B-24’s assigned to the 210 x 300mm, 177pp plus bibliography. £15.00 th 8 USAF, 1942-45. Paul Andrews/William Adams. 421pp, spiral bound. £45.95 LOSSES OF THE US 8TH AND 9TH AIR FORCES by Stan D Bishop & John A Hey MBE THREE PUBLICATIONS PUBLISHED BY THE Covers losses on a day-to-day basis for two of the th 8 AIR FORCE MEMORIAL MUSEUM largest air strike forces ever assembled and committed FOUNDATION COMPILED BY PAUL to battle. Four Volume Series – each hardback with ANDREWS & WILLIAM HILL d/jckt, 210mm x 300mm These are text only, spiral bound and contain a wealth th of information for the researcher into 8 AF operations 010363 Vol 1: ETO Area June 1942-December during WWII. 1943. 542pp, b/w photos. £42.95 010372 Vol 2: ETO Area January 1944 – March 010349 ROLL OF HONOR: 652pp. Compre- 1944. 491pp, b/w photos. £59.00 hensive listing of all personnel lost, KIA, POW, INT. 010373 Vol 3: ETO Area, April 1944 to June 1944. Information included is: aircraft serial no, date, group, £59.00 MACR No, crew position and fate. £54.95 010374 Vol 4:ETO Area, July 1944 – Sept 1944. 717pp, £69.00 010350 COMBAT CHRONOLOGY: 446pp. -

Bombing the European Axis Powers a Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945

Inside frontcover 6/1/06 11:19 AM Page 1 Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 Air University Press Team Chief Editor Carole Arbush Copy Editor Sherry C. Terrell Cover Art and Book Design Daniel M. Armstrong Composition and Prepress Production Mary P. Ferguson Quality Review Mary J. Moore Print Preparation Joan Hickey Distribution Diane Clark NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page i Bombing the European Axis Powers A Historical Digest of the Combined Bomber Offensive 1939–1945 RICHARD G. DAVIS Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 2006 NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page ii Air University Library Cataloging Data Davis, Richard G. Bombing the European Axis powers : a historical digest of the combined bomber offensive, 1939-1945 / Richard G. Davis. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-148-1 1. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations. 2. World War, 1939-1945––Aerial operations––Statistics. 3. United States. Army Air Forces––History––World War, 1939- 1945. 4. Great Britain. Royal Air Force––History––World War, 1939-1945. 5. Bombing, Aerial––Europe––History. I. Title. 940.544––dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Book and CD-ROM cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii NewFrontmatter 5/31/06 1:42 PM Page iii Contents Page DISCLAIMER . -

AAHS FLIGHTLINE #187, 2Nd Quarter 2014

AAHS FLIGHTLINE No. 187, Second Quarter 2014 American Aviation Historical Society www.aahs-online.org The Belgian air force participated with a number of General Dynamics F-16AMs as seen here with FA-127. (All photos by the author) Red Flag 14-2 by Wayne Minert Red Flag 14-2 was held March 3-14. Interdiction forces included F-15Es Highlights of What’s Inside This year’s event was only two weeks of the 4th FW, 366th FS from Seymour compared to the usual three, and there Johnson AFB, S.C., and B-52Hs from was a substantially different feeling to the 2nd BW, 96th BS based in Barksdale the event. The number of participants AFB, Louisiana. - Red Flag 14-2 was down from the last Red Flag. The Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses event almost had the feeling of a smaller (SEAD) provided an advantage for - Best of the Best expeditionary force, as opposed to the the interdiction force. This role was - AAHS-Online.org Update larger coalition force structure of the performed by F-16 CJs of the 20th FW, past. 77th FS from Shaw AFB, South Carolina. - Cindy Ann, WWII Aviation The participants who provided Red Naval aircraft from CAW 5, EAS 141 Tribute Air (the enemy) were members of the NAF Atsugi, Japan, fl ying EA-18Gs also 65th Aggressor squadron in F-15Cs and participated in the SEAD role. They the 64th Aggressor squadron in F-16s apparently were launching from Fallon Regular Sections based at Nellis AFB, Nev., that have NAS in northern Nevada. -

History from the Middle: the Case of the Second World War* I

History from the Middle: The Case of the Second World War* I Paul Kennedy Abstract Writing on modern warfare lately has tended to focus upon two vital but divergent trends, which might be termed the War from Above and War from Below schools of analysis. This essay concentrates instead upon the middle levels of warfare, drawing examples from mid-World War Two, where the chief operational objectives of the Allies were clearly established (at Casablanca, January 1943), but had yet to be realized. The realization of such military goals as defeat of the U-boat threat, or gaining domination of the air over Europe, in turn required breakthroughs that could only come from what one might term “the mid- level managers of war”-inventors, scientists, civil servants, captains of naval squadrons, and commanders of air groups. Scholars of these campaigns have long recognized the importance of the changes that occurred at the operational level of war between 1943 and 1944; this essay offers a larger synthetic analysis of their argument. his paper, in the memory of George C. Marshall’s extraordinary role as the greatest of the Grand Alliance’s generals-cum-politicians, concentrates upon, andT develops a theory about, the operational and tactical history of the middle * Being the 2009 Annual George C. Marshall Foundation Lecture, sponsored by the George C. Marshall Foundation and the Society for Military History, and delivered at the annual meet- ing of the American Historical Association, in New York, Sunday, 4 January 2009. Paul Kennedy is the Director of International Security Studies and the J.