To See the 2018 Bryant Literary Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Krist Novoselic

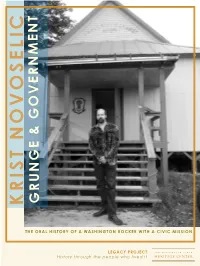

OVERNMENT G & E GRUNG KRIST NOVOSELIC THE ORAL HISTORY OF A WASHINGTON ROCKER WITH A CIVIC MISSION LEGACY PROJECT History through the people who lived it Krist Novoselic Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes October 14, 2008 John Hughes: This is October 14, 2008. I’m John Hughes, Chief Oral Historian for the Washington State Legacy Project, with the Offi ce of the Secretary of State. We’re in Deep River, Wash., at the home of Krist Novoselic, a 1984 graduate of Aberdeen High School; a founding member of the band Nirvana with his good friend Kurt Cobain; politi cal acti vist, chairman of the Wahkiakum County Democrati c Party, author, fi lmmaker, photographer, blogger, part-ti me radio host, While doing reseach at the State Archives in 2005, Novoselic volunteer disc jockey, worthy master of the Grays points to Grays River in Wahkiakum County, where he lives. Courtesy Washington State Archives River Grange, gentleman farmer, private pilot, former commercial painter, ex-fast food worker, proud son of Croati a, and an amateur Volkswagen mechanic. Does that prett y well cover it, Krist? Novoselic: And chairman of FairVote to change our democracy. Hughes: You know if you ever decide to run for politi cal offi ce, your life is prett y much an open book. And half of it’s on YouTube, like when you tried for the Guinness Book of World Records bass toss on stage with Nirvana and it hits you on the head, and then Kurt (Cobain) kicked you in the butt . -

Mahaquizzer 2009 Answers

KQA MAHAQUIZZER ANSWERS The 2009 edition DO NOT OPEN TILL THE END OF THE 90MIN SMALL SPELLING VARIATIONS ARE OKAY, USE YOUR JUDGEMENT FOR ALL ANSWERS WHICH ARE NAMES OF PEOPLE, JUST SURNAME IS ACCEPTABLE. HOWEVER, IF SURNAME IS CORRECT AND FIRST NAME(S) ARE GIVEN WRONGLY, IT IS TO BE CONSIDERED INCORRECT NO HALF POINTS FOR ANY QUESTION IF IN DOUBT, CALL APPU (+91 98452 03004) or ARUL (+91 97312 14519) or THEJASWI UDUPA (+91 98867 25754) It is an Italian sweet consisting of almonds in hard sugar-coating. Speakers of the English language should ignore a homophony and not throw it during 1 celebrations. What? Confetti / Confetto If the pseudonymous first names of the siblings were Currer, Ellis and Acton, Bell (Bronte not 2 what would their pseudonymous surname be? acceptable) This physical fitness system is named after its Greek-German creator, who originally called his method 'Contrology' because he believed his method used the mind to control muscles. He was interned as an enemy alien by Britain during World War I, and he used his method to help his fellow internees. What 3 do we know it as now? Pilates In the late 1960s, a neurologist wrote a non-fiction book about his patients at Beth Abraham Hospital N.Y., who had been victims of the encephalitis lethargica epidemic. The book inspired a play by Harold Pinter, and a 1990 4 Oscar-nominated film starring Robert De Niro and Robin Williams. Who? Oliver Sacks It was invented by a naval engineer in 1945. During the Vietnam war, thousands were shipped to be used as wireless antennae. -

The Shutter by Miloš Urban

The Shutter by Miloš Urban Translated by Dominik Jun CLICK Eyes adrift in the early evening and around them a face. Two murky beads illuminated by white light. A rushing figure, weaving between the coats and jackets of a bustling Náměstí Republiky, filled with people flowing in all directions and then back again. Matěj stopped and studied her. Someone bumped into him, but Matěj was the one who offered an apologetic “excuse me”. She disappeared behind a man’s shoulder before reappearing again, now in profile, as if showing off her nose. Did she notice him? Perhaps she saw how he couldn’t help but gaze in her direction. But he could only see a single eye – the left one. It had long black eyelashes, and twinkled with the reflection of Christmas tree that the girl was mysteriously studying. She threw a brief quizzical look directly at Matěj before hastily turning away and heading towards the shopping centre. A passing tram hooted in her direction, forcing her to abruptly stop mid-step while broadcasting a guilty grin. Sitting inside a glass cabin, the infuriated female tram driver slapped her hand on her head for all to see. The girl’s eyes once again found him amidst the mass of people, and when they spotted Matěj’s evident relief that nothing had happened to her – that she had not become a fatality, that her legs and toes weren’t laying dismembered on the tracks, sliced off by the passing tram – then both threw each other a smile. Their mouths widened, teeth exposed. -

Ent-2002-03-15.Pdf (752.9Kb)

ENTERTAINMENTpage 21 Technique • Friday, March 15, 2002 • 21 Gravity dragging you? What’s the Buzz? You might like the Jennifer Nettles That’s what the Technique asked the ENTERTAINMENT Band’s new release entitled Gravity: baseball team’s junior catcher Tyler Drag me Down. They’re playing Parker in a new question-and-answer Technique • Friday, March 15, 2002 Eddie’s Attic tomorrow. Page 23 column in Sports. Page 29 It’s ‘Showtime’ for De Niro and Murphy Eddie Murphy and Robert De Niro take comedic antics to the crime scene in director Tom Dey’s dangerously funny new cop-action spoof Showtime. William Shatner also makes an appearance as none other than himself. By Chris Webb holds a boot camp, so that the Staff Writer officers can “properly” jump onto car hoods and test for drugs. Of Film: Showtime course, TJ Hooker never had to Studio: Warner Bros. deal with the reality of car repair Starring: Robert De Niro, or as Preston explains, “There’s Eddie Murphy, Rene Russo a reason why cops don’t taste MPAA Rating: PG-13 cocaine, it could be cyanide.” Rating: yyy 1/2 In further hopes of making Preston a bigger star, the pro- Eddie Murphy and Robert ducers replace his land yacht for De Niro put on a badge and a jet-black Hummer and con- lay on the laughs in Showtime. vert his living room into a ad- The movie is a lampoon of TV vertisement for Ikea. Their hands shows such as Miami Vice and even renovate the police station movies like the Lethal Weapon from a grungy mess of papers series. -

Polish Territorial Demands Accepted in Full by Czechs

AVERAGE D4JLT CBCVlATIOIf **• Month o f September, ItSS p r ic e t h r e e ce n te Where Germani Win March Into Czechoslovakia PLANS COMPLETtD POLISH TERRITORIAL FOR THE ELECTtoN DEMANDS ACCEPTED . — ^ , t. d o v b u b w e d d in g Seek Large Vote For dioice ALL-RELATIVE AFFAIR Of Town Officials; bnpor- Reading. Pa.. O ct 1.— (A P ).- IN FULL BY CZECHS Brothers married sisters in a double ceremony that was an all- OENTER PARK’S EAGLE' tant Eyenmg Session To family-relative affalrL Patrick C. I ^ a t o , 19, wed Edith Stump, GERMAN MAIN a t t e m p t e d t o ESCAPE Threatraed- h ram A f«f 17, and Ralph Donato, 17, mar Pass On Appropriations. k ed Helen Stump, 18. Mayor J. -Vi’ S.® ?*“ *** *•«'* perched .®*nag pole on Henry Stump, who officiated, la toe knojl at Center Park, flew edByAcdoi^PartOfCil^f a relative of the bridea BODY CROSSES away^wito toe storm. It landed jW R MALCOLM STANDARD In tome of toe shrubbery nearby Of TesdMn To Be Tnun^ Wth the eelectlon o t Judfe Her- ana was able to keep out of sight Teld w . O enity to act aa olectton CZEC^O R D ER for a couple, of days. It i w . moderator on Monday during the however, discovered by a mem ferr?dB(rfore2P.M .Tei GROUP S1VDIES ber at toe police department and , town election, arrangements for the was taken into custody. snnual balloUng are complete. In ReconnoHering Priecede Ar* ^ e eagle to now held at toe morrow; Direct NofotkH ^ t e of the attacks ,on th r e a t In police stoUoo unUl such time as the local political sttuationn^e by HOW TO FILL lormng; arrangemente can be made to We stories of flood and hurricane properly place It on its usual tkms To Sotde Matters during the past week, a cursory P®’* broken check indicates that a fairly heavy 3,000 Meters Neotral toe atorm. -

Men's Soccer, Field Hockey Teams Give Brown the Hues

Men's soccer, field hockey teams give Brown the Hues Seebackpage __^_______——___———_______________________________________________--___~—-—_______——_.^-——————————_ tEbe lath} (ffettntnta Serving the Storrs Community Since 1896 Vbi LXXXVIIINo. 39 The University of Connecticut Thursday, Nov. 1, 1984 KennedycampaignsforMondale, other stale Democrats in Waterbury By Paul Thiel topher Dodd. Staff Writer Kennedy, who received a three-minute stands WATERBURY— U.S Senator Edward M Ken- ing ovation when he arived here, stressed party nedy (D-Mass.) accused President Ronald unity and the need of the Democrats to defeat Reagan of "masquerading as a Democrat" and President Reagan Charging Reagan with "being offering voters nothing but "empty platitudes" tough on poor, young mothers, but easy with during rallies for Democratic Congressional the Pentagon," and making "shallow appeals to candidates and the Mondale/Ferraro ticket here selfishness," Kennedy said "He (Reagan) is out and in New Haven Wednesday afternoon of depth, and should be out of office." U.S. Reps Buce Morrison, of the 3rd District, Kennedy criticized Reagan's foreign and and 5th District Rep* Bill Ratchford were the domestic policies, and his habit of quoting past main beneficiaries of rallies in a downtown New Democratic presidents. "Ronald Wilson Reagan H^ven church and at the Hamilton Park Pavillion has no right to quote John Fitzgerald Kennedy," here Both face tough Republican challengers the senator said "But I can see why he does it— on Nov. 6: Morrison, a freshman, is involvedin a who would want to be associated with heated contest against former U.S. Rep. Larry (Republicans) Harding Coolidge, Hoover and DeNardis, while Ratchford faces two-term State Dewey?" Representative John Rowland Ratchford who Saying Reagan is "the biggest spender in his- is going for his fourth term, has called the tory," Kennedy said the Reagan defense plan is race "intense." wasteful. -

Spartan Daily Serving San José State University Since 1934

WEATHER SOCIAL MEDIA SPORTS A&E FFollow us on TTwitter Sharks prepare to ‘Nevermind’ the age, @@spartandaily bite into Red Wings Nirvana’s still got it BecomeB a fan oon Facebook High: 70° ffacebook.com/ Low: 49° PAGE 4 PAGE 6 sspartandaily Spartan Daily Serving San José State University since 1934 Wednesday, April 27, 2011 spartandaily.com Volume 136, Issue 45 New Student Union construction proceeds with work on foundation Nic Aguon integrity of the area being Staff Writer drilled.” “Within a week or two, we will be testing the piles and As construction of the new take data of the soil on the con- Student Union continues, the struction site,” Shum said. “The next step in the process is to data will tell the contractors test the foundation. how sustainable the soil is and “To lessen the amount of if it’s ready to be constructed noise, we have to utilize a dif- upon.” ferent pile-driving system,” said He also said the soil on the Bill Shum, director of planning construction site needs to be design and construction. leveled and that the soil in the He said the construction San Jose area is “full of sedi- team will be using a pile driv- ments composed of clay and ing system on the site called solid materials.” auger cast piles. The construction team According to EXOFOR wants to make sure there is no Foundations, a company that obstruction when the drill is specializes in drilling services, brought in, Shum said. auger cast piles allow “the con- He said the construction Photo: Brian O’Malley / Spartan Daily struction of piles with minimal team is in the process of re- Fatima Acevedo, a sophomore social work major, reads about the life of a human traffi cking victim. -

Magazin Ausgabe 09-2003

Plattenbörsen Oldie Markt 09/03 3 Plattenbörsen 2003 Datum Stadt/Land Veranstaltungs-Ort Veranstalter / Telefon 7. September Linz/Österreich Volkshaus Bindermichl Werner Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 13. September Mannheim Alte Feuerwache Wolfgang W. Korte (061 01) 12 86 62 13. September München Kolpinghaus Werner Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 14. September Dortmund Westfalenhalle Goldsaal Manfred Peters (02 31) 48 19 39 14 September Frankfurt Jahrhunderthalle Wolfgang W. Korte (061 01) 12 86 62 14. September Berlin TU-Mensa Michael Kohls (0 30) 341 10 35 14. September Innsbruck/A Hüttenberger Saal Werner Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 14. September Budapest/Ungarn Varosilget, Petöfi Csarnok Lemezbörze (00 36) 14 30 09 90 20. September Salzburg/A Kleingmainer Saal Werner Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 20. September Wien/Österreich Stadthalle Discpoint (00 43) 19 67 75 50 20. September Amsterdam/NL RAI ARC (00 31) 229 21 38 91 21. September Nürnberg Meistersingerhalle Stefan Meiner (03 41) 699 56 80 21. September Regensburg Antoniussaal Werner Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 25. September Berlin Statthaus Böcklerpark Kurt Wehrs (030) 425 03 00 27. September Karlsruhe Badnerlandhalle Neureut Ludwig Reichmann (01 79) 697 43 12 27. September Zwickau Clubhaus Sachsenring Stefan Meiner (03 41) 699 56 80 27. September Wiener Neustadt/A Ungarviertel-Zentrum Discpoint (00 43) 19 67 75 50 28. September Passau Nibelungenhalle Werner Stoschek (085 09) 26 09 28. September Leipzig Uni Mensa Stefan Meiner (03 41) 699 56 80 28. September Trier Europahalle Wolfgang W. Korte (061 01) 12 86 62 28. September Graz/Österreich Kolpinghaus Discpoint (00 43) 19 67 75 50 28. -

![714.01 [Cover] Mothernew3](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1282/714-01-cover-mothernew3-6211282.webp)

714.01 [Cover] Mothernew3

BREAKING BENJAMIN NEW MUSIC REPORT REVIEWED: BECK, CAVE IN, LUNA, TERRANOVA, PEACHES, BLACK DICE... Issue 783 • October 7, 2002 • www.cmj.com SPOTLIGHT PLUS MORE! Last Chance To Pre-Register For CMJ Music Marathon RYKODISC’SRYKODISC’S Big $ Savings! See Page 21! PLATINUMPLATINUM STATION PROFILE WDET/DETROIT EXPOSED! ANNIVERSARYANNIVERSARY LOUD ROCK Rykodisc's George Howard and Trevor Jones HELLBENT FOR PLEATHER! CMJ RETAIL DISTURBED DEBUTS AT NO. 1 CHARTS: SLEATER-KINNEY STILL NO.1, HOT WATER MUSIC MOST ADDED 1. Obvious Things 2. Sunshine 3. All Along 4. Maybe We Wont Die 5. Good Thing You're Young 6. Easy Target 7. Strange Situation 8. World Without You 9. Not a Sinner 10. Prefers Fall Be A SEX JUNKIE! See Lava Baby as they headline “The Passion Tour” 10/8 – James Madison University, Hightown Pavilion 10/10 – Duke University, George’s Garage 10/11 – UNC-Chapel Hill, Pantana Bob’s 10/13 – University of Virginia, Starr Hill 10/18 – University of Georgia, The Last Call 10/19 – Georgia Tech University, The Library Bar & Grill Check out www.lavababy.com for more dates… Powderfinger 1-800-356-1155 [email protected] Roger Schrader 1-877-740-4620 www.pilot-radio.com [email protected] 10/7/2002 Issue 783 • Vol 73 • No. 4 FEATURES 8 Rykodisc Turns 20 One of America’s largest and most successful independent record companies, Rykodisc has made its living by anticipating change, staying one step ahead of the competition and, of course, signing the best talent available. With a catalogue that includes albums from such artists as Frank Zappa, Nick Drake, Morphine, Sugar, Chuck E. -

A NEW WAY to BUY BILLBOARD!! I

$6.95 (U.S.), $8.95 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) aw a zw THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO, AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT OCTOBER 19, 2002 Latin Acts Expand Presence At Arenas First View $40411.4010 0ki14 M.,. ç.. 0.4 ..:. ir As Tour Popularity Grows, Sponsorship Dollars Follow 401e74w.u; . aw, q M irvx,4400 yM;)\,Rb<..Y' rAU7 wa BY LEILA COBO and Vicente & Alejandro Fernán- a..er.e-4,..n i ,.,N .,Oad r -- w n.o a rA. len MIAMI -As the fall touring season dez. Their presence underscores . YErN.4e FO^ CU1 Y , m., Ï , gets under way, Latin artists -pre- the growing importance and eco- ra., _. , «,r,. e,, ., viously rare birds on the main- nomic viability of Latin tours, even stream arena circuit as it raises concerns -are showing up in about oversaturation. unprecedented num- Some of the big Lat- bers, often sharing the in acts have hit select Web Premieres Log On same markets within arenas in the past but days of each other. never to the extent -or Among the Latin headliners on with the attention -seen this year. As Key Marketing Tool major U.S. tours this fall are Shaki- Allison Winkler, an agent for the ra, Marc Anthony, Enrique Iglesias, Creative Artists Agency -whose BY BRIAN GARRITY generate traffic that can climb Maná, Carlos Vives, Juan Gabriel, (Continued on page 81) NEW YORK -Faced with fre- into the millions daily. quent leaks of new music on AOL Music GM Bill Wilson peer-to -peer networks, the major says, "In a time of radio consol- labels are stepping up their own idation where playlists are get- use of the Internet to preview ting tighter and in a time where House OKs Webast Royalty new releases in carefully orches- MTV is playing a lot less videos, trated campaigns that build a the music industry is looking buzz ahead of for additional out- Bill; Foes Take Case To Senate street date. -

TECHNIQUE Pete in NCAA Swimming Employees Work to Keep “The South’S Liveliest College Newspaper” and Diving Championships

Friday, April 5, 2002 Four Tech students com- Spring cleaning—students and TECHNIQUE pete in NCAA swimming employees work to keep “The South’s Liveliest College Newspaper” and diving championships. campus green. ONLINE http://cyberbuzz.gatech.edu/technique SPORTS page 35 FOCUS page 13 Serving Georgia Tech since 1911 • Volume 87, Issue 29 • 36 pages Opinions 6 · Focus 13 · Entertainment 19 · Comics 28 · Sports 36 Mullin named People in Motion Riding the Segway OIT director Amendments John Mullin was named the new Director of OIT, marking the end of a search ruled invalid that began last fall. Mullin replaces Gordon Wishon, who left to accept a position at SGA forced to call special election to Notre Dame. OIT also pro- moted Ron Hutchins to a amend constitution after UJC decision newly created position de- By Jody Shaw one that bans discrimination in signed to meet the techno- News Editor student organizations—passed logical demands of Tech’s by only a two vote margin. academic and research com- The Undergraduate Judicia- The first amendment con- munities. Mullin, who has ry Cabinet ruled that recently cerns the UJC. It increases the been serving as interim Di- passed amendments to the Un- number of justices from ten to rector since Wishon’s depar- dergraduate Student Govern- twelve members, allows justices ture, came to Tech in 1994. ment Constitution are invalid. to hear cases over the summer, SGA plans to hold a special elec- and provides an interim Chief tion April 17-19 to revote on Justice be appointed in emer- Relay for Life the three proposals, as well as a gency situations. -

The Knight Volume 13: Issue 5 Nova Southeastern University

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks The urC rent NSU Digital Collections 2-2003 The Knight Volume 13: Issue 5 Nova Southeastern University Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper NSUWorks Citation Nova Southeastern University, "The Knight Volume 13: Issue 5" (2003). The Current. 625. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nsudigital_newspaper/625 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the NSU Digital Collections at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Current by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ~ NEWS t,, ENTERTAINMENT ~ SPORTS Volume 13 Issue 5 February 2003 NSUNEWS©@NOVA.EDU Famed Journalist Delivers Speech at Farquhar ., INSIDE College Renaming Ceremony LO O ~ ; by Todd Collins suing 12 pages of questions regard [email protected] ing the prospect of war in Iraq, and CAMPUS NEWS ,,_ was granted 4 hours of President ~----·-----·--·---···---···--.. -·----·--···-·. ,-,---------·- ---· 475 people turned out on Monday Bush's time in response. This is ates evening, February 10, at the. Rose and Alfred tament not only to Bush's candor, but Miniachi P~rfoI'Il).ingAits Center for the cer also to Woodward's standing as a jour emony.to inaug~ate the Farquhar College of ' nalist. .. Arts and Sciences' new name. Guest speaker Woodward wrapped up the cer was Bob Woodward. Having achieved fame New Physics Minor emony with a signing for his recently .. , for his part in exposing the Watergate scandal released book, Bush at War, which pages · during the Nixon era, Woodward is currently chronicles the activities of major U.S.