MEIEA 2010.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wavelength (December 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 12-1981 Wavelength (December 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (December 1981) 14 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ML I .~jq Lc. Coli. Easy Christmas Shopping Send a year's worth of New Orleans music. to your friends. Send $10 for each subscription to Wavelength, P.O. Box 15667, New Orleans, LA 10115 ·--------------------------------------------------r-----------------------------------------------------· Name ___ Name Address Address City, State, Zip ___ City, State, Zip ---- Gift From Gift From ISSUE NO. 14 • DECEMBER 1981 SONYA JBL "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans. " meets West to bring you the Ernie K-Doe, 1979 East best in high-fideUty reproduction. Features What's Old? What's New ..... 12 Vinyl Junkie . ............... 13 Inflation In Music Business ..... 14 Reggae .............. .. ...... 15 New New Orleans Releases ..... 17 Jed Palmer .................. 2 3 A Night At Jed's ............. 25 Mr. Google Eyes . ............. 26 Toots . ..................... 35 AFO ....................... 37 Wavelength Band Guide . ...... 39 Columns Letters ............. ....... .. 7 Top20 ....................... 9 December ................ ... 11 Books ...................... 47 Rare Record ........... ...... 48 Jazz ....... .... ............. 49 Reviews ..................... 51 Classifieds ................... 61 Last Page ................... 62 Cover illustration by Skip Bolen. Publlsller, Patrick Berry. Editor, Connie Atkinson. -

Wavelength (November 1984)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 11-1984 Wavelength (November 1984) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (November 1984) 49 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/49 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I I ~N0 . 49 n N<MMBER · 1984 ...) ;.~ ·........ , 'I ~- . '· .... ,, . ----' . ~ ~'.J ··~... ..... 1be First Song • t "•·..· ofRock W, Roll • The Singer .: ~~-4 • The Songwriter The Band ,. · ... r tucp c .once,.ts PROUDLY PR·ESENTS ••••••••• • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ••••••••• • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • • • • ••••••••••• • •• • • • • • • • ••• •• • • • • • •• •• • •• • • • •• ••• •• • • •• •••• ••• •• ••••••••••• •••••••••••• • • • •••• • ••••••••••••••• • • • • • ••• • •••••••••••••••• •••••• •••••••• •••••• •• ••••••••••••••• •••••••• •••• .• .••••••••••••••••••:·.···············•·····•••·• ·!'··············:·••• •••••••••••• • • • • • • • ...........• • ••••••••••••• .....•••••••••••••••·.········:· • ·.·········· .....·.·········· ..............••••••••••••••••·.·········· ............ '!.·······•.:..• ... :-=~=···· ····:·:·• • •• • •• • • • •• • • • • • •••••• • • • •• • -

By David Kunian, 2013 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents

Copyright by David Kunian, 2013 All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Chapter INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 1 1. JAZZ AND JAZZ IN NEW ORLEANS: A BACKGROUND ................ 3 2. ECONOMICS AND POPULARITY OF MODERN JAZZ IN NEW ORLEANS 8 3. MODERN JAZZ RECORDINGS IN NEW ORLEANS …..................... 22 4. ALL FOR ONE RECORDS AND HAROLD BATTISTE: A CASE STUDY …................................................................................................................. 38 CONCLUSION …........................................................................................ 48 BIBLIOGRAPHY ….................................................................................... 50 i 1 Introduction Modern jazz has always been artistically alive and creative in New Orleans, even if it is not as well known or commercially successful as traditional jazz. Both outsiders coming to New Orleans such as Ornette Coleman and Cannonball Adderley and locally born musicians such as Alvin Battiste, Ellis Marsalis, and James Black have contributed to this music. These musicians have influenced later players like Steve Masakowski, Shannon Powell, and Johnny Vidacovich up to more current musicians like Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison, and Christian Scott. There are multiple reasons why New Orleans modern jazz has not had a greater profile. Some of these reasons relate to the economic considerations of modern jazz. It is difficult for anyone involved in modern jazz, whether musicians, record -

Session Abstracts (Final)

2010 ARSC Conference [FINAL] A&R: JAZZ Thursday 11:15a-12:30p Session 1 Session Abstracts for Thursday Hidden Gems: Preserving the Benny Carter and Benny Goodman Collections Ed- ward Berger, Vincent Pelote, and Seth Winner, Institute of Jazz Studies, Rutgers University, THE SOUNDS OF NEW ORLEANS Newark, NJ Thursday 8:45a-10:45a Plenary Session In 2009 the Institute of Jazz Studies received a major grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to digitize two of its most significant bodies of sound recordings: the Benny WELCOME David Seubert, President, ARSC Carter and Benny Goodman Collections. The Carter Collection comprises the multi- The opening session introduces us to the music of New Orleans and the rich history of instrumentalist/arranger/composer’s personal archive and contains many unique perform- recording in the city. ances, interviews, and documentation of events in Carter’s professional life. Many of these tapes and discs were donated by Carter himself, and the remainder by his wife, Hilma, shortly after Carter’s death in 2003. The Goodman Collection consists of reel-to- RECORD MAKERS AND BREAKERS: NEW ORLEANS AND SOUTH LOUISIANA, 1940S- reel tapes compiled by Goodman biographer/discographer D. Russell Connor over four 1960S: RESEARCHING A REGION'S MUSIC John Broven, East Setauket, NY decades and donated by him in 2006. It represents the most complete collection of This presentation will be based on Broven’s three books: Walking to New Orleans: The Goodman recordings anywhere. As friend and confidant to Goodman, Connor had access Story of New Orleans R&B (1974, republished as Rhythm & Blues in New Orleans in to the clarinetist’s personal archive, as well as those of many Goodman researchers and 1978), South to Louisiana: The Music of the Cajun Bayous (1983), and Record Makers collectors worldwide. -

The Golden Age of Rock 'N' Roll

The Golden Age of Rock ’n’ Roll Week 5, March 19, 2018 1956 (part 2): Elvis, Fats, Little Richard Assignment: “The Story of Blue Suede Shoes” http://www.rebeatmag.com/carl-perkins-elvis-blue-suede-shoes-story/ Rolling Stone: “The Rope: The Forgotten History of Segregated Rock & Roll Concerts” http://www.rollingstone.com/music/features/rocks-early-segregated-days-the- forgotten-history-w509481 Little Richard profile with rare photos: http://www.history-of-rock.com/richard.htm Listen to: Church Bells May Ring, The Willows, 1956 (#62 Pop, #12 R&B) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tLl1eDAWMeA [optional] Compare: The Diamonds, 1956 (#14 Pop) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IdBN-hOmtVE Fever, Little Willie John, 1956 (#1 R&B) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i93-hlwULUk [optional] Compare: Peggy Lee, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kjy2sZ8yBGQ Be-Bop-A-Lula, Gene Vincent, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O4_5593-skQ Page !1 Oh What a Night, The Dells, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z1ozQT8yQXA I Walk the Line, Johnny Cash, 1956 (#1 Country; #19 Pop) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lq0fUa0vW_E There is a key change between each of the five verses, and Cash hums the new root note before singing each verse. The final verse, a reprise of the first, is sung a full octave lower than the first verse. My Blue Heaven, Fats Domino, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CS75X7perbI Sold over 5 million copies in 1928 as recorded by Gene Austin. Money Honey, Elvis Presley, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R-4KROtI1yM Compare: The Drifters (McPhatter) (1953) https://youtu.be/N8oNHMNCSjQ Roll Over Beethoven, Chuck Berry, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zD80CostTV0 The Magic Touch, The Platters, 1956 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iVX6f3OZ35o * * * * Some notes (to be discussed in class): FATS DOMINO -Born in New Orleans. -

JAMES BROWN Tennessee (1928) Or Georgia (1933) ¡©Si

r ; k Jf ||p ji „ > ■ Ip > V - » I ■ JAMES BROWN Tennessee (1928) or Georgia (1933) ¡©Si- James Brown once said of Elvis Presley, “He recorded at Harlem’s Apollo Theater on September taught white America to get down.” Brown himself 24th, 1962, sold a million copies and remained on did Elvis one better in that regard: he encouraged ev the Billboard charts for more than a year, an unprec eryone to do it. Brown, an indefatigable performer edented achievement for a hard-core R&B album. In who still maintains a grading touring schedule for has 1965, with the success of “Papa’s Got a Brand New fine-tuned funk revue, has earned many tides over the Bag” and “I Got You (I Feel Good),” Brown proceed years. ed to break his sound down to a groove as basic and He’s been called “the Hardest-Working Man in bad as you could get. That same year, rock and roll Show Business.” As an impoverished child of the De fans were willingly hoodwinked by the slickly re pression, Brown picked cotton, shined shoes and hearsed drama of Brown’s fainting-and-reviving ritual danced for spare change on the streets. He also during “Please Please Please” in The TAJUJ. Show. served time in a reform atory and tried his hand at He’s been called “Soul Brother Number One” for boxing and baseball. When a leg injury put an end to his willingness to “say it loud, I’m black and I’m his big-league pitching aspirations, Brown turned to proud.” In 1968, when he was addressing black so music. -

Wavelength (December 1984)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 12-1984 Wavelength (December 1984) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (December 1984) 50 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/50 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF NEW ORLEANS EARL K LONG LIBRARY ACQUISITIONS DEPT NEW ORLEANS. LA 70148 1101 S.PETERS PHVSALIA PRODUCTION PRESENTATION NOONE UNOER18 ADMITTED ISSUE NO. 50 e DECEMBER 1984 "''m not sure, but I'm almost she1o's positive, that all music came from New Orleans." -Ernie K-Doe, 1979 D EPARTMENTS LIVE BANDS EVERY December News .... .... .. .. ... 4 Golden Moments . ........... ..... 8 NIGHT OF THE WEEK Flip City . ......... ............. 8 (NO COVER EVER!!!) New Bands ....... ..... .. ... 10 Caribbean . .. .. ........ ... .. .. 12 ENTRANCE ON SOUTH PETERS BETWEEN JULIA & ST. JOSEPH Dinette Set . ......... ............ 14 Rare Record . .. .... .. .. ... ... 16 Reviews . .. ...... ..... ... ... 16 shei Ia's features local, national, Listings . .. ........... .. .. .. 23 and international groups such as ... Last Page . ....................... 30 FEATURES Number 50 . 19 Dear Santa .. .... .. .. .. .. 22 Lady Rae New Orleans 1984 .... .. .. .. ... 25 Neville Brothers The Cold Records .. ........ ... .. ...... 31 One-Stops . .. .. ..... .. .. .. 35 Radia!ors HooDoo Guru's Hanoi Rocks Tim Shaw Cover design by Steve St. Germam. For informa Belfegore Java tion on purchasing cover art, ca/1 504/895-2342. John Fred & The Playboys Mrolberof f Habit JD & The Jammers Force o . -

Specialty Records Early Discography

Specialty Records Early Discography Ben Siegel and Art Rupe started with Premier Records in Los Angeles in late 1943, where Siegel co- authored songs for such rising stars as Nat “King” Cole. The label released three singles during the first half of 1944 and then experienced trouble. In late September, Premier announced that it was becoming Atlas Records, while Siegel and Rupe started up a company together. Juke Box Records was formally a label associated with the United Record Company – no doubt leaving room for expansion. Juke Box released just one single near the end of the year, and that one came out with no fanfare. “Boogie #1” / “When He Comes Home to Me” Sepia Tones Juke Box UR-100 Recorded on August 21, 1944, and released: late 1944 The first pressing sported a white label with red print – a combination that only appeared on this particular single. Before the end of the year, Juke Box had switched to a black label with silver print. As the year’s end, United decided to promote their record nationally. As they did so, they traded the B- side in for a song with “Blues” in the title. “Boogie #1” / “Sophisticated Blues” The Sepia Tones Juke Box UR-100 First Appearance in Trade Magazines: January 13, 1945 The first pressing with the new B-side promoted the artist in large, bold type. Despite lackluster reviews, the single continued to sell. Juke Box billed it as being part of a “Hot Classic Series.” They also added their address to the label. The next pressing reduced the size of the artist name. -

The Gospel Side of Specialty Records – the Post-War Period

The Gospel Side of Specialty Records – The Post-War Period by Opal Louis Nations A historical backdrop: It is generally acknowledged that almost from the start of Art Rupe’s involvement in the country’s popular vernacular musics, gospel and spiritual expressions were among his keenest passions. He would often drop in on a church gospel program and sometimes shed a tear when moved by a particular jubilee quartet spinning on a phonograph. Rupe told me that during his boyhood he was exposed to gospel music emanating from the open windows in the summer from the African American Baptist church in his hometown neighborhood in Pennsylvania. Rupe did not fit the stereotypical hard-nosed, cash-driven, stogie-stompin’ record mogul. He was an intelligent, quiet, analytical and compassionate character who not only got involved in disseminating black talent to make a quick buck but genuinely enjoyed the musics he put out. At the close of gospel’s golden age, when the 1960s came around, the popular music industry began to transform itself into one that conjoined politics with culture. 1964 saw the advent of “The British Invasion.” A year later rock & roll had fully matured into rock and its separate audiences had blended into one and, says Philip H. Ennis in his 1992 book, The Seventh Stream (the seven different types of popular __________________________________________________________ The Gospel Side of Specialty Records, p./1 © 2011 Opal Louis Nations music, published by Wesleyan University Press), the musical materials and performers from the separate streams were combined to form a new and different idiom with its own artists and music. -

Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination

Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hamilton, John C. 2013. Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11125122 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination A dissertation presented by Jack Hamilton to The Committee on Higher Degrees in American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2013 © 2013 Jack Hamilton All rights reserved. Professor Werner Sollors Jack Hamilton Professor Carol J. Oja Rubber Souls: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination Abstract This dissertation explores the interplay of popular music and racial thought in the 1960s, and asks how, when, and why rock and roll music “became white.” By Jimi Hendrix’s death in 1970 the idea of a black man playing electric lead guitar was considered literally remarkable in ways it had not been for Chuck Berry only ten years earlier: employing an interdisciplinary combination of archival research, musical analysis, and critical race theory, this project explains how this happened, and in doing so tells two stories simultaneously. -

And a Letter to My Customers ===

--- == ROOTS & RHYTHM - SALE 01/12/2014 - AND A LETTER TO MY CUSTOMERS === --- Dear Friends Happy New Year! We hope you all had a wonderful holiday season. NOTE: Regrettably our holiday season was the slowest we've ever seen and it may mean that we will not be able to continue operating our business for very much longer. I am no longer a young man (not by a long shot!) and don't have the energy to pursue ways in which we may be able to promote the business. I would love to be able to settle down and listen to all the music I have gathered over the years in a relaxed setting and with critical reviewing faculties turned off. I would love to see Roots & Rhythm continue and thrive and even if we make it through the current crisis I would still like to get away from the stress of running a business so I am open to having someone else take over and move the company forward. If you are such a person or know such a person please contact me and we can discuss it. This list consists of a sale which we hope will raise enough money to help us get caught up with our suppliers and our taxes as well as some other pressing expenses. This list features 600 titles in all covering all the genres of music we specialize in and featuring books, DVDs and compact discs. This list includes manufacturer?s overstocks and deletions, our own excess inventory and a lot of titles that have been sitting on our shelves that have never been listed before. -

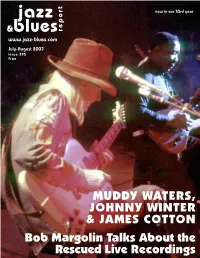

July-August 295-WEB

jazz now in our 33rd year &blues report www.jazz-blues.com July-August 2007 Issue 295 Free MUDDY WATERS, JOHNNY WINTER & JAMES COTTON Bob Margolin Talks About the Rescued Live Recordings MUDDY WATERS, JOHNNY WINTER Published by Martin Wahl Communications & JAMES COTTON Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Duane Verh Talks With Bob Margolin About the Recordings From the 1977 Live Tour Layout & Design Bill Wahl That Were ‘Rescued From the Dumpster’ Operations Jim Martin Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Check out our costantly updated website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 years of reviews are up and we’ll be going all the way back to 1974. Address all Correspondence to.... Jazz & Blues Report 19885 Detroit Road # 320 Rocky River, Ohio 44116 Bob Margolin & Muddy Waters Photo: Watt Casey Jr. Main Office ...... 216.651.0626 Editor's Desk ... 440.331.1930 By Duane Verh Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com In 1976, blues legend Muddy Waters parted ways with the legendary Chess Web .................. www.jazz-blues.com Records label which, by that time, had only its name in common with the Copyright © 2007 Martin-Wahl Communications Inc. company’s founders. He then hooked up with blues/rock guitar idol Johhny No portion of this publication may be Winter who produced Muddy’s first release for the CBS-distributed Blue Sky reproduced without written permission label.