1 Gender Trouble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By STUDIO)

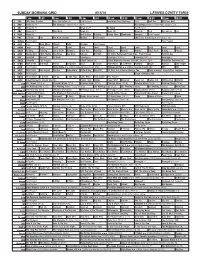

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by STUDIO) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Studio Title Female + Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A+E Studios, LLC Knightfall 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC Six 8 4 50% 4 50% 1 13% 3 38% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC UnReal 10 4 40% 6 60% 0 0% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC Lifetime Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Alameda Productions, LLC Netflix Alcon Television Group, Expanse, The 13 2 15% 11 85% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Expanding Universe Syfy LLC Productions, LLC Amazon Hand of God 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 3 30% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon I Love Dick 8 7 88% 1 13% 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow Streaming Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Just Add Magic 26 7 27% 19 73% 0 0% 4 15% 1 4% 0 2 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Kicks, The 9 2 22% 7 78% 0 0% 0 0% 2 22% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Man in the High Castle, 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0 Reunion MITHC 2 Amazon Prime The Productions Inc. -

Winter 2017 Calendar of Events

winter 2017 Calendar of events Agamemnon by Aeschylus Adapted by Simon Scardifield DIRECTED BY SONNY DAS January 27–February 5 Josephine Louis Theater In this issue The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane by Kate DiCamillo 2 Leaders out of the gate Adapted by Dwayne Hartford 4 The Chicago connection Presented by Imagine U DIRECTED BY RIVES COLLINS 8 Innovation’s next generation February 3–12 16 Waa-Mu’s reimagined direction Hal and Martha Hyer Wallis Theater 23 Our community Urinetown: The Musical Music and lyrics by Mark Hollmann 26 Faculty focus Book and lyrics by Greg Kotis 30 Alumni achievements DIRECTED BY SCOTT WEINSTEIN February 10–26 34 In memory Ethel M. Barber Theater 36 Communicating gratitude Danceworks 2017: Current Rhythms ARTISTIC DIRECTION BY JOEL VALENTÍN-MARTÍNEZ February 24–March 5 Josephine Louis Theater Fuente Ovejuna by Lope de Vega DIRECTED BY SUSAN E. BOWEN April 21–30 Ethel M. Barber Theater Waa-Mu 2017: Beyond Belief DIRECTED BY DAVID H. BELL April 28–May 7 Cahn Auditorium Stick Fly by Lydia Diamond DIRECTED BY ILESA DUNCAN May 12–21 Josephine Louis Theater Stage on Screen: National Theatre Live’s In September some 100 alumni from one of the most esteemed, winningest teams in Encore Series Josephine Louis Theater University history returned to campus for an auspicious celebration. Former and current members of the Northwestern Debate Society gathered for a weekend of events surround- No Man’s Land ing the inaugural Debate Hall of Achievement induction ceremony—and to fete the NDS’s February 28 unprecedented 15 National Debate Tournament wins, the most recent of which was in Saint Joan 2015. -

One Bruised Apple

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Stonecoast MFA Student Scholarship 2017 One Bruised Apple Stacie McCall Whitaker University of Southern Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/stonecoast Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Whitaker, Stacie McCall, "One Bruised Apple" (2017). Stonecoast MFA. 29. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/stonecoast/29 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stonecoast MFA by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. One Bruised Apple __________________ A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE STONECOAST MFA IN CREATIVE WRITING BY Stacie McCall Whitaker __________________ 2017 Abstract The Quinn Family is always moving, and sixteen-year-old Sadie is determined to find out what they’re running from. In yet another new neighborhood, Sadie is befriended by a group of teens seemingly plagued by the same sense of tragedy that shrouds the Quinn family. Sadie quickly falls for Trenton, a young black man, in a town and family that forbids interracial relationships. As their relationship develops and is ultimately exposed, the Quinn family secrets unravel and Sadie is left questioning all that she thought she knew about herself, her family, and the world. iii Acknowledgements To my incredible family: Jeremy, Tyler, Koralynn, Damon, and Ivan for your support, encouragement, sacrifice, and patience. -

Life Inside the Spectacle: David Foster Wallace, George Saunders, And

Hawkins 1 Life Inside the Spectacle: David Foster Wallace, George Saunders, and Storytelling in the Age of Entertainment A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English By John C. Hawkins 1 April 2013 Hawkins 2 Introduction In 1996, David Foster Wallace released Infinite Jest, a 1,079 page, 388-footnote monster of a novel in which Canadian terrorists fight to gain control of a form of entertainment so pleasurable it traps the viewer in an unbreakable loop of repeated watching, literally amusing the victim to death. Wallace set the story in an American system that has annexed its northern states onto Canada in order to dump its garbage there, a political move so expensive that the government has to license the year to the highest bidder. In the midst of this entertainment- obsessed, hyper-commercialized post-America, the residents of a Boston tennis academy and a nearby halfway house struggle with family histories and addictive behaviors, trying to cope with overwhelming feelings of isolation and an inability to connect with loved ones, even as government agents and foreign spies try to locate a master copy of the tape for mass distribution. Ten years later, George Saunders published In Persuasion Nation, a swift collection of quickly-paced short stories organized into four sections. Saunders arranges the stories topically around different challenges facing American society in the decade following the World Trade Center attacks of 2001, a time when political and religious fervor combined with an entertainment-based advertising complex to form overly simplistic responses to complex international situations. -

'It Was Phenomenal'

INSIDE TODAY: Beach town reels over chief’s death after gun investigation / A3 SEPT. 11, 2016 JASPER, ALABAMA — SUNDAY — WWW.MOUNTAINEAGLE.COM $1.50 INSIDE ‘It was phenomenal’ Foothills No. 1 Tide wins ugly Festival TUSCALOOSA — There’s still plenty draws large of work to do for the top-ranked Alabama crowd, Crimson Tide. / B1 great talent BRIEFS By NICOLE SMITH Daily Mountain Eagle One injured Foothills Festival 2016 after shooting was a success as people from all over the state and sur- on college rounding areas came to campus downtown Jasper to enjoy musical performances, food, MONTGOMERY shopping and entertain- (AP) — College offi- ment. cials say one per- On Friday, the Foothills son has been Festival kicked off with per- formances by Ernie McClin- injured after a ton with Shotgun, Adam shooting on the Thousands of people from across the Southeast were Hood and one of the week- end’s most anticipated per- campus of a school in Jasper Saturday to see a variety of musical acts as in Alabama. formers, Deana Carter. The part of this year’s Foothills Festival, including, clock- variety of music continued Local news media wise from top, Tonic, Hero the Band, Vallejo, Alvin on Saturday, with a military reports that the per- Garrett and Gin Blossoms. For more photos from this band performance and tunes from Two Jimmy Band, son suffered non- year’s free music festival in downtown Jasper, see A4 life threatening Alvin Garrett, Michael and A12 of today’s Eagle. “Rudy” Glasgow, Hero the injuries after the Band, The Vorpal Sword, shooting occurred Vallejo, Looksy, Tonic and in a parking lot at Smashley. -

The Complete Ask Scott

ASK SCOTT Downloaded from the Loud Family / Music: What Happened? website and re-ordered into July-Dec 1997 (Year 1: the start of Ask Scott) July 21, 1997 Scott, what's your favorite pizza? Jeffrey Norman Scott: My favorite pizza place ever was Symposium Greek pizza in Davis, CA, though I'm relatively happy at any Round Table. As for my favorite topping, just yesterday I was rereading "Ash Wednesday" by T.S. Eliot (who can guess the topping?): Lady, three white leopards sat under a juniper-tree In the cool of the day, having fed to satiety On my legs my heart my liver and that which had been contained In the hollow round of my skull. And God said Shall these bones live? shall these Bones live? And that which had been contained In the bones (which were already dry) said chirping: Because of the goodness of this Lady And because of her loveliness, and because She honours the Virgin in meditation, We shine with brightness. And I who am here dissembled Proffer my deeds to oblivion, and my love To the posterity of the desert and the fruit of the gourd. It is this which recovers My guts the strings of my eyes and the indigestible portions Which the leopards reject. A: pepperoni. honest pizza, --Scott August 14, 1997 Scott, what's your astrological sign? Erin Amar Scott: Erin, wow! How are you? Aries. Do you think you are much like the publicized characteristics of that sun sign? Some people, it's important to know their signs; not me. -

Sunday Morning Grid 8/14/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/14/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Incredible Dog Challenge Paid Golf Res. PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Rio Olympics Track and Field. (N) Å Rio Olympics Women’s Basketball: China vs. U.S. 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 2016 U.S. Senior Open Final Round. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Mom Mkver Church Faith Dr. John Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Eat Dirt-Axe 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage (TV14) Å Leverage (TV14) Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Tigres República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Home Alone 3 › (1997, Comedia) Alex D. -

Issue 191.Pmd

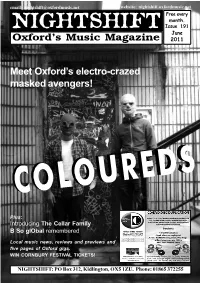

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 191 June Oxford’s Music Magazine 2011 Meet Oxford’s electro-crazed masked avengers! COLOUREDSCOLOUREDS Plus: Introducing The Cellar Family B So glObal remembered Local music news, reviews and previews and five pages of Oxford gigs. WIN CORNBURY FESTIVAL TICKETS! NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net COWLEY ROAD CARNIVAL However, we hope everyone will will be a South Park-only event understand that it is the right one this year after the organisers were to make in the financial unable to secure enough funding to circumstances.” cover the cost of staging the event For more info on Fiesta and on Cowley Road itself. Carnival, visit Carnival In South Park will go www.cowleyroadcarnival.co.uk ahead over the weekend of the 2nd- rd YOUNG KNIVES are among the latest set of acts to be confirmed for 3 July, with the Saturday night BBC OXFORD INTRODUCING Truck Festival. The local trio, who are currently on tour to promote event a fundraising fiesta headlined moves to a new day and time from th their new album, ‘Ornaments From The Silver Arcade’, and recently by Roots Manuva. this month. From May 29 the played an intimate set at Truck Store on Cowley Road as part of Carnival chairman John Hole dedicated local music show will go National Record Store Day, will join Gruff Rhys on the main stage on explained the decision to make this out on a Sunday at 9pm, moving the Saturday night. -

Basketball in Impressive Fashion with a Game and the Indians Did District Win at Orange Park Not Disappoint the Packed High on Friday

1A SUNDAY, DECEMBER 22, 2013 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.50 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Columbia, Fort White Doggie clothes a SUNDAY EDITION bring home great last-minute wins. 1B Christmas gift. 1C HUMANE SOCIETY Bones FOR SALE? finds a A brief history home of LSHA, HMA By TONY BRITT [email protected] The Lake Shore Hospital Authority is an independent special state taxing district. It was established original- ly to construct and operate Lake Shore Hospital. In 1987, the hospital was leased to Santa Fe Healthcare and in 1996, FILE it was leased to Shands A public hearing has been set for Monday, Jan. 13 at 5:15 p.m. in regards to the proposed merger and Healthcare. potential sale of Lake Shore Regional Medical Center. Under the lease arrange- ment, the authority entered into an indigent care agree- Shands Lake Shore may go on the block ment with the hospital for the hospital to take care By TONY BRITT By the numbers Shore Hospital Authority of Columbia County resi- [email protected] Administrative Complex, the dents’ emergencies. hospital records building and Through the agreement JASON MATTHEW WALKER/Lake City Reporter The pending merger $7.6 billion proposed cost all vacant lands. the authority pays 50 per- Mary Booker adopted Bones on Friday. of Lake Shore Regional of acquisition In July Shands Lake Shore cent of indigent in-patient Medical Center’s parent com- $3.7 billion Health Manage- Regional Medical Center’s care and 30 percent of indi- Woman read of his pany, Health Management ment Associates’ debt that parent company, Health gent out-patient care. -

Religion, Ritual and Ritualistic Objects

Religion, Ritual and Ritualistic Objects Edited by Albertina Nugteren Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Religion, Ritual and Ritualistic Objects Religion, Ritual and Ritualistic Objects Special Issue Editor Albertina Nugteren MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Albertina Nugteren Tilburg University The Netherlands Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/Ritual) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03897-752-0 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03897-753-7 (PDF) c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Preface to ”Religion, Ritual and Ritualistic Objects” ......................... ix Albertina Nugteren Introduction to the Special Issue ‘Religion, Ritual, and Ritualistic Objects’ Reprinted from: Religions 2019, 10, 163, doi:10.3390/rel10030163 .................. -

I. HOT NEW Release,I

September 13, 1993 Volume 8 • BILLY Co. Op ...‘0, • JOEL • a.'a:e • • , 17..•. • • .,.. NERS .. , -.... aetw i. ICKS e-'41REAXOUTS _ 'r-WILD •• •4 '. .:•. e Y * REM W13,... — vr."------...... 'PR11%1 Pk/WB':•-"....eAkIAH CAREY Columbia "S eat -A CA WINCE PPk/w8 SPIN DOCTO p& Ass 'C'e` Nis„_ THE BREEDERS Electro ..., GARTH BROOKS Liberty lee ......e.e, ,agr:el .2.94,,..D.z..„TrI _ ista. _ -rtMELLENCAMP Merc ' GABRIEUE Go Discs% on ;TING A&M • B. -1-10.1LNSBY RCA LOS LOBOS Slash/Aqiiithe 'ye i "Alii, fie...t r: HOT NEW RELEASe,i_S._ - e. .. 44.... * lb_ - ,1 4e, ,im e' 11. .„:•,...... ACtIOF BASE • 'PIG COUNTRY ee, COMING OF AGE «IN "N` JUDYBATS -11'^' - "" If That She Wants The One I Love .. Coming Home To Love Ugly On The Outside Wild Wore' - «Arista 07822-12614 RCA RDJ 62654-2 r Zoo ZP17135-2 / tirte/WI .4-1e394., 1,08.p`.,,isie4 G 4-873013, e ,!•[,,e, . THE THE CHERYL "PEEâIl" RILEY SALT-N-PEP SILK Ildri: * IL•P „op I Guess.rellftetove , Shoop ItElektrp Had Td 88 Be eel I Love Is Stronger Than.. • Reprise N/A NP/Lon/PLG 422 8 Epic ESK 5108 .40 e. • Itiee,Aaget NG FORA Management: Idolma 01993 London RI September 13, 1993 Volume 8 Issue 359 $6.00 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher Cat In The LENNY BEER Editor In Chief SINGLES 8 Hat Is Back TONI PROFERA It's still Mariah Carey, far far ahead of the field. Executive Editor DAVID ADELSON Vice President/Managing Editor KAREN GLAUBER DIALOGUE 34 Vice President/Post Modem Editor Billy Joel has it all — a#1 album, ahit single, ared-hot career MICHAEL ST. -

The Origins of St. Patrick's Day the Dangers of Mass Hysteria

The Badger Pause Volume 14, Issue 5 14510 N. Cheshire Street, Burton Ohio March 2018 The origins of St. Patrick’s Day by Nick Misconin, BP Staff Writer St. Patrick’s Day is an annual holiday of St. Patrick’s commonly celebrated by those of Irish Day activities descent across North America. Does would be most this mean that all Irish people celebrate bigger cities the holiday? Well, not quite. St. Pat- having parades rick’s Day in the United States is very to celebrate the different from the St. Patrick’s Day in day. Another Ireland. activity for the It all started a long time ago in 17th adults is drink- century Ireland when the Catholic ing alcohol, Church, the Lutheran Church, the East while everyone Orthodox Church, and the Church of consumes other Ireland declared March 17th the feast Irish foods day of St. Patrick. St. Patrick became and drinks. the patron saint of Ireland, and March Soda bread 17th was chosen because it was the day and corned he died in the 5th century. Nowadays, beef&cabbage however, the holiday is spectacularly are probably different. the two most Today St. Patrick’s Day is not exactly popular, both the same as it was centuries ago. You of which I can see, St. Patrick’s Day has spread from personally rec- the U.S. Originally, it was a feast day, ommend. but now it is commonly celebrated to Considering Photo coutesy of timeanddate.com commemorate those of Irish descent. the holiday has A group of people celebrating St.