Kevin Richard Kaiser

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Set in Maine

Books Set in Maine Books Set in Maine Author Title Location Andrews, William D. Mapping Murder Atwood, Margaret The Handmaid's Tale Bachman, Richard Blaze Barr, Nevada Boar Island Acadia National Park One Goal: a Coach, a Team, and the Game That Brought a Divided Town Bass, Amy Together Lewiston Blake, Sarah The Guest Book an island in Maine Blake, Sarah Grange House A resort in Maine 2/26/2021 1 Books Set in Maine We Were an Island: the Maine life of Art Blanchard III, Peter P and Ann Kellam Placentia Island Bowen, Brenda Enchanted August an island in Maine Boyle, Gerry Lifeline Burroughs, Franklin Confluence: Merrymeeting Bay Merrymeeting Bay Chase, Mary Ellen The Lovely Ambition Downeast Maine Chee, Alexander Edinburgh Chute, Carolyn The Beans of Egypt Maine Coffin, Bruce Robert Within Plain Sight Portland 2/26/2021 2 Books Set in Maine Coffin, Bruce Robert Among the Shadows Portland Creature Discomforts: a dog lover's Conant, Susan mystery Acadia National Park Connolly, John Bad Men Maine island Connolly, John The Woman in the Woods Coperthwaite, William S. A Handmaid Life Portland Cronin, Justin The Summer Guest a fishing camp in Maine The Bar Harbor Retirement Home For DeFino, Terri-Lynne Famous Writers Bar Harbor Dickson, Margaret Octavia's Hill 2/26/2021 3 Books Set in Maine Doiron, Paul Almost Midnight wilderness areas Doiron, Paul The Poacher's Son wilderness areas Ferencik, Erika The River at Night wilderness areas The Stranger in the Woods: the extraordinary story of the last true Finkel, Michael hermit Gerritsen, Tess Bloodstream Gilbert, Elizabeth Stern Men Maine islands Gould, John Maine's Golden Road Grant, Richard Tex and Molly in the Afterlife\ 2/26/2021 4 Books Set in Maine Graves, Sarah The Dead Cat Bounce (Home Repair is HomicideEastport #1) Gray, T.M. -

2018 Brochure

THE COMMUNITY OF WRITERS 20I8 Summer Workshops... • Poetry Workshop: June 23 - 30 • Writers Workshops in Fiction, Nonfiction & Memoir: July 8 - 15 The Community of Writers For 48 summers, the Community of Writers at Squaw Valley has brought together poets and prose writers for separate weeks of workshops, individual conferences, lectures, panels, readings, and discussions of the craft and the business of writing. Our aim is to assist writers to improve their craft and thus, in an atmosphere of camaraderie and mutual support, move them closer to achieving their goals. The Community of Writers holds its summer writing workshops in Squaw Valley in a ski lodge at the foot of the ski slopes. Panels, talks, staff readings and workshops take place in these venues with a spectacular view up the mountain. ...& Other Projects • Published Alumni Reading Series: Recently published Writers Workshops alumni are invited to return to the valley to read from their books and talk about their journeys from unpublished writers to published authors. • Omnium Gatherum & Alumni News Blog: Chronicling the publication and other successes of its participants. • Craft Talk Anthology – Writers Workshop in a Book: An anthology of craft talks from the workshops, edited by Alan Cheuse and Lisa Alvarez. • Annual Benefit Poetry Reading: An annual event to raise funds for the Poetry Workshop’s Scholarship Fund. • Notable Alumni Webpage: A website devoted to a list of our notable alumni. • Facebook Alumni Groups: Social media alumni groups keep the community and conversation going. • Annual Poetry Anthology: Each year an anthology of poetry is published featuring poems first written during the Poetry Workshop in Squaw Valley. -

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

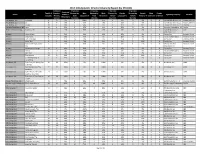

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By STUDIO)

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by STUDIO) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Studio Title Female + Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A+E Studios, LLC Knightfall 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC Six 8 4 50% 4 50% 1 13% 3 38% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC UnReal 10 4 40% 6 60% 0 0% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC Lifetime Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Alameda Productions, LLC Netflix Alcon Television Group, Expanse, The 13 2 15% 11 85% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Expanding Universe Syfy LLC Productions, LLC Amazon Hand of God 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 3 30% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon I Love Dick 8 7 88% 1 13% 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow Streaming Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Just Add Magic 26 7 27% 19 73% 0 0% 4 15% 1 4% 0 2 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Kicks, The 9 2 22% 7 78% 0 0% 0 0% 2 22% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Man in the High Castle, 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0 Reunion MITHC 2 Amazon Prime The Productions Inc. -

NEMLA 2014.Pdf

Northeast Modern Language Association 45th Annual Convention April 3-6, 2014 HARRISBURG, PENNSYLVANIA Local Host: Susquehanna University Administrative Sponsor: University at Buffalo CONVENTION STAFF Executive Director Fellows Elizabeth Abele SUNY Nassau Community College Chair and Media Assistant Associate Executive Director Caroline Burke Carine Mardorossian Stony Brook University, SUNY University at Buffalo Convention Program Assistant Executive Associate Seth Cosimini Brandi So University at Buffalo Stony Brook University, SUNY Exhibitor Assistant Administrative Assistant Jesse Miller Renata Towne University at Buffalo Chair Coordinator Fellowship and Awards Assistant Kristin LeVeness Veronica Wong SUNY Nassau Community College University at Buffalo Marketing Coordinator NeMLA Italian Studies Fellow Derek McGrath Anna Strowe Stony Brook University, SUNY University of Massachusetts Amherst Local Liaisons Amanda Chase Marketing Assistant Susquehanna University Alison Hedley Sarah-Jane Abate Ryerson University Susquehanna University Professional Development Assistant Convention Associates Indigo Eriksen Rachel Spear Blue Ridge Community College The University of Southern Mississippi Johanna Rossi Special Events Assistant Wagner Pennsylvania State University Francisco Delgado Grace Wetzel Stony Brook University, SUNY St. Joseph’s University Webmaster Travel Awards Assistant Michael Cadwallader Min Young Kim University at Buffalo Web Assistant Workshop Assistant Solon Morse Maria Grewe University of Buffalo Columbia University NeMLA Program -

The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil: (Includes the in Persuasion Nation Collection) Pdf

FREE THE BRIEF AND FRIGHTENING REIGN OF PHIL: (INCLUDES THE IN PERSUASION NATION COLLECTION) PDF George Saunders | 368 pages | 16 Apr 2007 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780747585961 | English | London, United Kingdom The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil: George Saunders Someone once wrote that producing comedy is a far harder art than penning tragedy. Shockingly, I believe it was a humorous writer who made this selfless observation. Whether accurate or not, what certainly is true is that whimsy is a surprisingly tricky ingredient to get the right measure of in writing. A tad too little and the result is weak and insipid, a dab too much and the brew is overbearing. And either way it is very, very easy to come over as smug. Think of the output of Punch in the 80s or a great deal of Radio 4 comedy today to see feel the horror of what can unfold. So when a writer gets it right, praise is due. In his satirical fantasy novella The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil published inand his short story collection In Persuasion Nation published in and now reprinted togetherSaunders hits the spot, lightly yet accurately. The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil hereafter referred to as Frightening is a dreamlike fairy story, twisted rotten. The other six citizens must wait their turn in the Short Term Residency Zone in the infinitely larger surrounding country of Outer Horner. Already existing at the sufferance of their benevolent surrounding power, the Inner Hornerites incur the wrath of the bounteous yet growingly impatient surrounding benefactors, when their small patch of ground sinks further into the earth. -

2014/2015 Omium Gatherum & Newsletter

2014-2015 Issue 19 omnium gatherum & newsletter ~ i~ COMMUNITY OF WRITERS AT SQUAW VALLEY GOT NEWS? Do you have news you would OMNIUM GATHERUM & NEWSLETTER like us to include in the next newsletter? The 2014-15, Issue 19 Omnium is published once a year. We print publishing credits, awards and similar new Community of Writers at Squaw Valley writing-related achievements, and also include A Non-Profit Corporation #629182 births. News should be from the past year only. P.O. Box 1416, Nevada City, CA 95959 Visit www.squawvalleywriters.org for more E-mail: [email protected] information and deadlines. www.squawvalleywriters.org Please note: We are not able to fact-check the submitted news. We apologize if any incorrect BOARD OF DIRECTORS information is published. President James Naify Vice President Joanne Meschery NOTABLE ALUMNI: Visit our Notable Alumni Secretary Jan Buscho pages and learn how to nominate yourself or Financial OfficerBurnett Miller a friend: Eddy Ancinas http://squawvalleywriters.org/ René Ancinas NotableAlumniScreen.html Ruth Blank http://squawvalleywriters.org/ Jan Buscho NotableAlumniWriters.html Max Byrd http://squawvalleywriters.org/ Alan Cheuse NotableAlumniPoets.html Nancy Cushing Diana Fuller ABOUT OUR ADVERTISERS The ads which Michelle Latiolais appear in this issue represent the work of Edwina Leggett Community of Writers staff and participants. Lester Graves Lennon These ads help to defray the cost of the Carlin Naify newsletter. If you have a recent or forthcom- Jason Roberts ing book, please contact us about advertising Christopher Sindt in our next annual issue. Contact us for a rate sheet and more information: (530) 470-8440 Amy Tan or [email protected] or visit: John C. -

Winter 2017 Calendar of Events

winter 2017 Calendar of events Agamemnon by Aeschylus Adapted by Simon Scardifield DIRECTED BY SONNY DAS January 27–February 5 Josephine Louis Theater In this issue The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane by Kate DiCamillo 2 Leaders out of the gate Adapted by Dwayne Hartford 4 The Chicago connection Presented by Imagine U DIRECTED BY RIVES COLLINS 8 Innovation’s next generation February 3–12 16 Waa-Mu’s reimagined direction Hal and Martha Hyer Wallis Theater 23 Our community Urinetown: The Musical Music and lyrics by Mark Hollmann 26 Faculty focus Book and lyrics by Greg Kotis 30 Alumni achievements DIRECTED BY SCOTT WEINSTEIN February 10–26 34 In memory Ethel M. Barber Theater 36 Communicating gratitude Danceworks 2017: Current Rhythms ARTISTIC DIRECTION BY JOEL VALENTÍN-MARTÍNEZ February 24–March 5 Josephine Louis Theater Fuente Ovejuna by Lope de Vega DIRECTED BY SUSAN E. BOWEN April 21–30 Ethel M. Barber Theater Waa-Mu 2017: Beyond Belief DIRECTED BY DAVID H. BELL April 28–May 7 Cahn Auditorium Stick Fly by Lydia Diamond DIRECTED BY ILESA DUNCAN May 12–21 Josephine Louis Theater Stage on Screen: National Theatre Live’s In September some 100 alumni from one of the most esteemed, winningest teams in Encore Series Josephine Louis Theater University history returned to campus for an auspicious celebration. Former and current members of the Northwestern Debate Society gathered for a weekend of events surround- No Man’s Land ing the inaugural Debate Hall of Achievement induction ceremony—and to fete the NDS’s February 28 unprecedented 15 National Debate Tournament wins, the most recent of which was in Saint Joan 2015. -

Book Reviews

135 Book reviews . Nancy L. Roberts, Book Review Editor ––––––––––––––––– Medium-Type Friends A Free Man: A True Story of Life and Death in Delhi by Aman Sethi Reviewed by Jeff harletS 136 Exploring the Intersection of Literature and Journalism Literature and Journalism: Inspirations, Intersections, and Inventions from Ben Franklin to Stephen Colbert by Mark Canada Reviewed by Thomas B. Connery 140 What the Receptionist Knew about Joe Mitchell The Receptionist: An Education at The NewYorker by Janet Groth Reviewed by Miles Maguire 143 How to: Learning the Craft You Can’t Make This Stuff Up: The Complete Guide to Writing Nonfiction from Memoir to Literary Journalism and Everything in Between By Lee Gutkind Reviewed by Nancy L. Roberts 146 The Fine Print: Uncovering the True Story of David Foster Wallace and the “Reality Boundary” Both Flesh and Not: Essays by David Foster Wallace Reviewed by Josh Roiland 147 Literary Journalism Studies Vol. 5, No. 2, Fall 2013 136 Literary Journalism Studies Medium-Type Friends A Free Man: A True Story of Life and Death in Delhi by Aman Sethi. New York: W.W. Norton, 2012. Hardcover, 240 pp., $24.95. Reviewed by Jeff Sharlet, Dartmouth College, United States alfway through this subtle heartbreak of a book, HMuhammad Ashraf, the “free man” of the title, phones Aman Sethi—author and co-protagonist, at- tentive ego to Ashraf’s titanic id—to tell Sethi that Satish is sick. Who is Satish? The one who is sick, of course. Why must you ask so many questions, Aman bhai (brother). And just like that, Sethi’s profile of Ashraf changes direction for thirty pages, becoming an account of sick Satish, whom Ashraf expects Sethi to look after. -

One Bruised Apple

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Stonecoast MFA Student Scholarship 2017 One Bruised Apple Stacie McCall Whitaker University of Southern Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/stonecoast Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Whitaker, Stacie McCall, "One Bruised Apple" (2017). Stonecoast MFA. 29. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/stonecoast/29 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stonecoast MFA by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. One Bruised Apple __________________ A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF FINE ARTS UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MAINE STONECOAST MFA IN CREATIVE WRITING BY Stacie McCall Whitaker __________________ 2017 Abstract The Quinn Family is always moving, and sixteen-year-old Sadie is determined to find out what they’re running from. In yet another new neighborhood, Sadie is befriended by a group of teens seemingly plagued by the same sense of tragedy that shrouds the Quinn family. Sadie quickly falls for Trenton, a young black man, in a town and family that forbids interracial relationships. As their relationship develops and is ultimately exposed, the Quinn family secrets unravel and Sadie is left questioning all that she thought she knew about herself, her family, and the world. iii Acknowledgements To my incredible family: Jeremy, Tyler, Koralynn, Damon, and Ivan for your support, encouragement, sacrifice, and patience. -

Editing David Foster Wallace

‘NEUROTIC AND OBSESSIVE’ BUT ‘NOT TOO INTRANSIGENT OR DEFENSIVE’: Editing David Foster Wallace By Zac Farber 1 In December of 1993, David Foster Wallace printed three copies of a manuscript he had taken to calling the “longer thing” and gave one to his editor, Michael Pietsch, one to a woman he was trying to impress, and one to Steven Moore, a friend and the managing editor of the Review of Contemporary Fiction, whose edits and cuts Wallace wished to compare with Pietsch’s. The manuscript, which Little, Brown and Company would publish as Infinite Jest in 1996, was heavy (it required both of Moore’s hands to carry) and, Moore recalled, unruly: It’s a mess—a patchwork of different fonts and point sizes, with numerous handwritten corrections/additions on most pages, and paginated in a nesting pattern (e.g., p. 22 is followed by 22A-J before resuming with p. 23, which is followed by 23A-D, etc). Much of it is single-spaced, and what footnotes existed at this stage appear at the bottom of pages. (Most of those in the published book were added later.) Several states of revision are present: some pages are early versions, heavily overwritten with changes, while others are clean final drafts. Throughout there are notes in the margins, reminders to fix something or other, adjustments to chronology (which seems to have given Wallace quite a bit of trouble), even a few drawings and doodles.1 Wallace followed some of Pietsch and Moore’s suggestions and cut about 40 pages from the first draft of the manuscript2, but before publication he added more than 200 pages of additional material, including an opening chapter that many critics have praised as the novel’s best and more than 100 pages of (often footnoted) endnotes.3 Editing Wallace could be demanding, and those who attempted it found themselves faced with the difficulty of correcting a man with a prodigious understanding of the byzantine syntactical and grammatical rules of the English language.