The Art Ambassador by Julia Reed.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Felix Issue 0985, 1994

loo<tF The Student Newspaper of Imperiaiperiall ColleqCollegee I 3DRI8B3iaCE||olrj g 210CT94 TCCB-tSCTIONj enamings benefits of the proposal had not. ANDREW DORMAN-SMITH been adequately debated. Professor Shaw said the name of Senior academics at. the. the Department itself does not Department, of Mineral Resources overly matter, and said he was, Engineering (MRE) have called "a believer in tradition". Professor for further discussions over a plan Shaw would not say if he sup- to rename the department. Earth ported the name change proposal. Resources Engineering has However, the new head of emerged as the favourite choice MRE, and Dean of the newly for a new name, after discussions established Graduate School of between college officials. the Environment, Professor The change has been mooted Woods, is believed to think the following a letter from the proposal is a 'great idea'. His role Professor John Archer, Pro- as Dean will be to coordinate the Rector, which asks for comments departments of Imperial, and to on the new title. Professor Archer, present the benefits for research said that he has received only one of the college in line with a review negative response to his letter, completed in May by Sir John and claimed that most of the Mason. department's staff agree with the The other two RSM depart- proposal. But Professor Archer ments may also change names. said discussions are continuing - The college's chief decision mak- despite the publication of an offi- ing body, the Management cial college note which says the Finnish Embassy Planning Group (MPG), has sug- Photo by Ivan Chan change will take place "shortly". -

Beverly Hills

briefs • City to subsidize $1.6 million briefs • City refuses to declare rudy cole • My recommendations loan for City Manager housing Page 3 opinion on subway route Page 4 for state office Page 6 ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES Issue 575 • October 7 - October 13, 2010 OUR 11th Beverly Hills’ Anniversary First Lady The Weekly’s interview with Lonnie Delshad cover story • pages 8-9 Few motorists would risk their lives by for anyone but a Democrat because it would briefs • Lively subway route hearing at briefs • Julian Gold announces rudy cole • Roxbury Park Page 2 candidacy for City Council Page 3 United city speaks Page 6 bicycle community in the region, and isn’t have disappointed his liberal mother. As ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com that part of our transportation problem? Too one of my favorite commentators, Dennis letters too few folks using alternate transportation Prager, pointed out in a recent article, so WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES means too many cars on the road. Bike- many registered Democrats vote for Left- Issue 574 • September 30 - October 6, 2010 friendly infrastructure not only protects wing candidates who do not share their Beverly High Athletic cyclists entitled to ride all of the streets in views for purely emotional, nonsensical Alumni to be inducted & email our city, but it reduces motorist liability too. reasons. In Rudy’s case, it is because his Simply put, bikes belong, so let’s plan for mother would disapprove of him voting into Hall of Fame them to accommodate bikes safely. -

Visualizing Levinas:Existence and Existents Through Mulholland Drive

VISUALIZING LEVINAS: EXISTENCE AND EXISTENTS THROUGH MULHOLLAND DRIVE, MEMENTO, AND VANILLA SKY Holly Lynn Baumgartner A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2005 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Kris Blair Don Callen Edward Danziger Graduate Faculty Representative Erin Labbie ii © 2005 Holly Lynn Baumgartner All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor This dissertation engages in an intentional analysis of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas’s book Existence and Existents through the reading of three films: Memento (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001), and Mulholland Drive, (2001). The “modes” and other events of being that Levinas associates with the process of consciousness in Existence and Existents, such as fatigue, light, hypostasis, position, sleep, and time, are examined here. Additionally, the most contested spaces in the films, described as a “Waking Dream,” is set into play with Levinas’s work/ The magnification of certain points of entry into Levinas’s philosophy opened up new pathways for thinking about method itself. Philosophically, this dissertation considers the question of how we become subjects, existents who have taken up Existence, and how that process might be revealed in film/ Additionally, the importance of Existence and Existents both on its own merit and to Levinas’s body of work as a whole, especially to his ethical project is underscored. A second set of entry points are explored in the conclusion of this dissertation, in particular how film functions in relation to philosophy, specifically that of Levinas. What kind of critical stance toward film would be an ethical one? Does the very materiality of film, its fracturing of narrative, time, and space, provide an embodied formulation of some of the basic tenets of Levinas’s thinking? Does it create its own philosophy through its format? And finally, analyzing the results of the project yielded far more complicated and unsettling questions than they answered. -

Collaborating with James Baldwin on a Screenplay of Giovanni's Room

DISPATCH “We can love one another in other ways”: Collaborating with James Baldwin on a Screenplay of Giovanni’s Room Michael Raeburn Abstract The author discusses his personal relationship with James Baldwin, recounting their collaboration on a film script for an adaptation of Giovanni’s Room. Keywords: Giovanni’s Room, Michael Raeburn, James Baldwin, film, Paris, Marlon Brando, Robert de Niro, Saint-Paul de Vence, Steve McQueen It was a bright summer’s afternoon in the south of France on 2 August 1977. In the garden of his house below the ramparts of the village of Saint-Paul de Vence, James Baldwin was celebrating his 53rd birthday. He made a brief speech thanking his friends for coming. Then, much to my surprise, he announced that he and I had embarked on “an adventure” to write a screenplay of Giovanni’s Room (1956). He raised his glass to me; most of the guests raised theirs to us in hesitant celebration. The idea had occurred a few weeks before. It came from Jimmy; I cannot call him James, as to me, and to all his friends, he was Jimmy. His offer to collaborate on the adaptation had come out of the blue. Only a set of mutually shared circum- stances going back to our first meeting can explain his proposal which was pre- sented to me in these words: “We can also love one another in other ways: we’ll write the script of ‘Giovanni’s Room’ together.” To most outsiders we were the most improbable match: a young, novice film- maker from colonial Africa, and a world-famous African-American writer from Harlem. -

General Awareness–Current Affairs Month of March-2019

GENERAL AWARENESS–CURRENT AFFAIRS MONTH OF MARCH-2019 List of Important Days March 1 - Zero Discrimination Day (Theme – “Act to change laws that Discriminate”) March 4 - National Safety Day (Themes – “Cultivate and Sustain A Safety Culture for Building Nation”) Mar 4-10 - National Safety Week March 7 - Janaushadhi Diwas March 8 - International Women’s Day (Theme – “Think Equal, Build Smart, Innovate for Change”). March 12 - World Day against Cyber Censorship March 12 - 30th anniversary of the World Wide Web (WWW) March 14 - (2nd Thursday of March) World Kidney Day (Theme - “Kidney Health for Everyone Everywhere”) March 14 - Pi Day (Pi's value (3.14)) March 15 - World Consumer Rights Day (In India this day is celebrated as Viswa Upabhokta Adhikar Diwas). (Theme – “Trusted Smart Products”) March 20 - International Day of Happiness. (Theme – “Happier Together”) March 20 - World Day of Theatre for Children and Young People March 20 - World Sparrow Day. (Theme – “I LOVE Sparrows”) March 21 - International Day of Forests. (Theme “Forests and Education”) March 21 - World Poetry Day March 21 - World Down Syndrome Day March 21 - International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (Theme – “Mitigating and countering rising nationalist populism and extreme supremacist ideologies”) March 21 - World Puppetry Day March 22 - World Water Day (Theme – “Leaving no one behind”) March 23 - World Meteorological Day (Theme – “The Sun, the Earth and the Weather”) March 23 - 88th Shaheed Diwas (Martyr’s Day) March 24 - World Tuberculosis (TB) Day (Theme – “It’s time”) March 25 - International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and Transatlantic Slave Trade. (Theme – “Remember Slavery: The Power of the Arts for Justice”) March 26 - Independence Day of Bangladesh March 27 - World Theatre Day (WTD) March 30 - Rajasthan Diwas Reserve Bank of India • The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has fined Yes Bank ₹1 crore for not complying with its directions about SWIFT, a financial messaging software. -

Special History Study, Jimmy Carter National Historic Site and Preservation District, 29

special history study november 1991 by William Patrick O'Brien JIMMY CARTER NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE AND PRESERVATION DISTRICT • GEORGIA UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR / NATIONAL PARK SERVICE TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v PREFACE vii INTRODUCTION 1 VISION STATEMENT 2 MAP - PLAINS AND VICINITY 3 PART ONE: BACKGROUND AND HISTORY BACKGROUND AND HISTORY 7 SOUTHWEST GEORGIA - REGION AND PLACE 9 SOUTHWEST GEORGIA - PEOPLE (PRE-HISTORY TO 1827) 11 SOUTHWEST GEORGIA, SUMTER COUNTY AND THE PLAINS OF DURA (1827-1865) 14 FROM THE PLAINS OF DURA TO JUST PLAIN "PLAINS" (1865-1900) 21 THE ARRIVAL AND PROGRESS OF THE CARTERS (1900-1920) 25 THE WORLD OF THE CARTERS AND JIMMY'S CHILDHOOD (1920-1941) 27 THE WORLD OUTSIDE OF PLAINS (1941-1953) 44 THE END OF THE OLD ORDER AND THE BEGINNING OF THE NEW: RETURN TO PLAINS (1953-1962) 46 ENTRY INTO POLITICS (1962-1966) 50 CARTER, PLAINS AND GEORGIA: YEARS OF CHANGE AND GROWTH - THE RISE OF THE NEW SOUTH (1966-1974) 51 PRESIDENTIAL VICTORY, PRESIDENTIAL DEFEAT (1974-1980) 55 THE CHRISTIAN PHOENIX AND THE "GLOBAL VILLAGE" - CARTER AND PLAINS (1980-1990) 58 CONCLUSION 63 PART TWO: INVENTORY AND. ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL RESOURCES - JIMMY CARTER NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE AND PRESERVATION DISTRICT INTRODUCTION 69 EXTANT SURVEY ELEMENTS - JIMMY CARTER NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE AND PRESERVATION DISTRICT 71 I. Prehistory to 1827 71 II. 1827-1865 72 III. 1865-1900 74 IV. 1900-1920 78 V. 1920-1941 94 VI. 1941-1953 100 iii VII. 1953-1962 102 VIII. 1962-1966 106 IX. 1966-1974 106 X. 1974-1980 108 XI. 1980-1990 109 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR ADDITIONAL SURVEY ELEMENTS PLAINS, GEORGIA . -

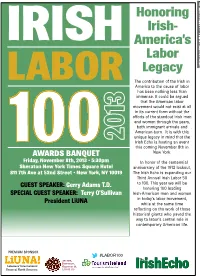

Irishecholabor100magazine

Page 17 Honoring / Irish Echo / NOVEMBER 6 - 12, 2013 / www.irishecho.com Irish- IRISH America’s Labor Legacy LABOR The contribution of the Irish in America to the cause of labor has been nothing less than immense. It could be argued that the American labor 3 movement would not exist at all 1 in its current form without the efforts of the standout Irish men and women through the years, 0 both immigrant arrivals and American-born. It is with this unique legacy in mind that the 2 Irish Echo is hosting an event this coming November 8th in AWARDS BANQUET New York. Friday, November 8th, 2013 • 5:30pm In honor of the centennial Sheraton New York Times Square Hotel anniversary of the 1913 lockout, 811 7th Ave at 52nd Street • New York, NY 10019 The Irish Echo is expanding our Third Annual Irish Labor 50 GUEST SPEAKER: Gerry Adams T.D. to 100. This year we will be honoring 100 leading SPECIAL GUEST SPEAKER: Terry O’Sullivan Irish-American men and women in today’s labor movement, President LiUNA while at the same time reflecting on the work of those historical giants who paved the way to labor’s central role in contemporary American life. PREMIUM SPONSOR #LABOR100 The ARCHER, BYINGTON, Laborers’ International GLENNON & IrishEcho Union of North America LEVINE LLP Page Page 18 IRISH LABOR 100 The Irish gave life to American labor By Terry O'Sullivan and leading various labor organizations. [email protected] For many of these warriors of the working class, their work is more than a n this centennial year of the historic job, and larger than a career; it is a Dublin Lockout, it is fitting that we lifetime's commitment. -

THE POINT WHERE THEY MEET and OTHER STORIES a Thesis

THE POINT WHERE THEY MEET AND OTHER STORIES A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts by Brittany Stone May 2011 Thesis written by Brittany Stone M.F.A., Kent State University, 2011 B.A., Hiram College, 2008 Approved by _____________Robert Pope______________, Advisor, MA Thesis Defense Committee ___________Varley O’Connor____________, Members, MA Thesis Defense Committee _____________Robert Miltner____________, Members, MA Thesis Defense Committee Approved by ____________Ron Corthell_______________, Chair, Department of English ___________John R.D. Stalvey____________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………....vi A REAL HOLLYWOOD PRODUCTION…………………………………………….1 THE SPIDER………………………………………………………………………….23 THE POINT WHERE THEY MEET…………………………………………………46 BOBCAT……………………………………………………………………………...65 OF DESPERATION AND CARS…………………………………………………….75 THE HEN……………………………………………………………………………...92 AS GOOD AS MOTHER…………………………………………………………….111 THE HOUR BEFORE DEATH………………………………………………………128 SAILING MAN……………………………………………………………………….144 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work is dedicated to my grandparents, Gene and Garcia Burchett of Duck, West Virginia. They’ve shown me that beauty, love, and joy can thrive in adversity. Little bits of their spirits are in each of these stories. Brittany Stone 3/15/11, Kent, OH iv A REAL HOLLYWOOD PRODUCTION The man came on a Saturday morning and knocked on Bud’s door. The man didn’t know Bud and Bud didn’t know him. Bud had been sitting in the kitchen in his big old house, writing a check for the gas. For as long as he’d had been paying his own way—too many years, as far as he was concerned—bills came first on Saturday mornings. He tucked the pen behind his ear and answered the door. -

Jimmy Doolittle E Commander Behind the Legend

THE 17 DREW PER PA S Jimmy Doolittle e Commander behind the Legend Benjamin W. Bishop Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Air University Steven L. Kwast, Lieutenant General, Commander and President School of Advanced Air and Space Studies Thomas D. McCarthy, Colonel, Commandant and Dean AIR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ADVANCED AIR AND SPACE STUDIES Jimmy Doolittle The Commander behind the Legend Benjamin W. Bishop Lieutenant Colonel, USAF Drew Paper No. 17 Air University Press Air Force Research Institute Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Project Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jerry Gantt Bishop, Benjamin W., 1975– Copy Editor Jimmy Doolittle, the commander behind the legend / Tammi K. Dacus Benjamin W. Bishop, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF. pages cm. — (Drew paper, ISSN 1941-3785 ; no. 17) Cover Art, Book Design, and Illustrations Includes bibliographical references. Daniel Armstrong ISBN 978-1-58566-245-6 Composition and Prepress Production 1. Doolittle, James Harold, 1896-1993—Military leadership. Michele D. Harrell 2. Generals—United States—Biography. 3. Command of Print Preparation and Distribution troops—Case studies. 4. United States. Army Air Forces. Air Diane Clark Force, 8th. 5. World War, 1939-1945—Aerial operations, Amer- ican. I. Title. UG626.2.D66B57 2014 940.54’4973092—dc23 2014035210 AIR FORCE RESEARCH INSTITUTE AIR UNIVERSITY PRESS Published by Air University Press in February 2015 ISBN: 978-1-58566-245-6 Director and Publisher ISSN: 1941-3785 Allen G. Peck Editor in Chief Oreste M. Johnson Managing Editor Demorah Hayes -

Shadow of Doubt

Shadow of Doubt By SL Beaumont First published by Paperback Writers Publishing 2019 Copyright © 2019 by SL Beaumont All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise without written permission from the publisher. It is illegal to copy this book, post it to a website, or distribute it by any other means without permission. This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book and on its cover are trade names, service marks, trademarks and registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publishers and the book are not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. None of the companies referenced within the book have endorsed the book. First edition ISBN: 978-0-473-48370-8 2 Shadow of Doubt by SL Beaumont Part I 3 Shadow of Doubt by SL Beaumont Chapter 1 July 10 “For God’s sake, get one of the others to do it,” I said, exasperated, as I looked up from my computer at my boss who was leaning on the wall of my cubicle. “No. It’s your turn,” Andrew replied turning away, signaling an end to the conversation. I sighed and stood up, stretching my back. -

The Intrusion of Jimmy by P. G. Wodehouse

The Intrusion of Jimmy By P. G. Wodehouse 1 CONTENTS CHAPTER I. JIMMY MAKES A BET II. PYRAMUS AND THISBE III. MR. MCEACHERN IV. MOLLY V. A THIEF IN THE NIGHT VI. AN EXHIBITION PERFORMANCE VII. GETTING ACQUAINTED VIII. AT DREEVER IX. FRIENDS, NEW AND OLD X. JIMMY ADOPTS A LAME DOG XI. AT THE TURN OF THE ROAD XII. MAKING A START XIII. SPIKE'S VIEWS XIV. CHECK AND A COUNTER MOVE XV. MR. McEACHERN INTERVENES XVI. A MARRIAGE ARRANGED XVII. JIMMY REMEMBERS SOMETHING XVIII. THE LOCHINVAR METHOD XIX. ON THE LAKE XX. A LESSON IN PICQUET XXI. LOATHSOME GIFTS XXII. TWO OF A TRADE DISAGREE XXIII. FAMILY JARS 2 XXIV. THE TREASURE-SEEKER XXV. EXPLANATIONS XXVI. STIRRING TIMES FOR SIR THOMAS XXVII. A DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE XXVIII. SPENNIE'S HOUR OF CLEAR VISION XXIX. THE LAST ROUND XXX. CONCLUSION 3 CHAPTER I JIMMY MAKES A BET The main smoking-room of the Strollers' Club had been filling for the last half-hour, and was now nearly full. In many ways, the Strollers', though not the most magnificent, is the pleasantest club in New York. Its ideals are comfort without pomp; and it is given over after eleven o'clock at night mainly to the Stage. Everybody is young, clean-shaven, and full of conversation: and the conversation strikes a purely professional note. Everybody in the room on this July night had come from the theater. Most of those present had been acting, but a certain number had been to the opening performance of the latest better-than-Raffles play. -

People First Employment Stories 4

STORIES ABOUT PEOPLE WITH SIGNIFICANT DISABILITIES WORKING IN THE COMMUNITY VOLUME IV Of the POSSIBILITIES Series 2008 A Publication of People First Wisconsin PEOPLE FIRST WISCONSIN Marian Center for Nonprofits 3211 South Lake Drive Milwaukee, WI 53235 (414) 483-2546 (888) 270-5352 fax (414) 483-2568 www.peoplefirstwi.org Mary Clare Carlson of People First Wisconsin conducted the interviews and wrote the stories of those people featured in this booklet. Editor: Amy J McGrath The publication is funded by The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Medicaid Infrastructure Grant (MIG) CFDA No. 93.768 Wisconsin Department of Health Services/Pathways to Independence his is the fourth booklet of the POSSIBILITIES series. The goal of the series is to highlight and celebrate the lives of people with significant disabilities, especially T intellectual disabilities, who are living, learning and working in Wisconsin. Our hope is that these stories will introduce you to the many possibilities that now exist for people with significant disabilities to become active and contributing members of their communities. The first two booklets in the POSSIBILITIES series feature stories about people with significant disabilities who are building lives in the community outside of institutions. The third booklet and this fourth booklet feature stories that reflect the growing trend of people with significant disabilities working in integrated community employment. The number of integrated community employment options can be as great as the number of people with significant disabilities seeking employment. The beauty of integrated community employment is that there is never a need to resort to a one-size-fits-all model.